Designing the Western Wall Plaza: National and Architectural Controversies*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monzon Family History in Jerusalem

History in Jerusalem The Events and Personal Stories of the Monzon Family By Arye Monzon Translated by Benjamin Tisser 2 The Monzon Family History in Jerusalem With owner to my dear and loved wife, Ahuva My children Homi and her husband Yossi, Mosh and his wife Goldie, Oded and his wife Einat and all my wonderful grandchildren. Tamuz 5766, July 2007 Jerusalem Israel All rights reserved to the writer Arye Avraham Monzon – 2007 © 10 Aluf Yohai Ben-Nun St. Ramat Beit-Hakerem Jerusalem Tel: +972-77-8850895 Cell: +972-52-8802988 The Monzon Family History in Jerusalem 3 Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................2 Introduction .......................................................................................4 My Family Roots - The Monzon Family.........................................6 History of My Family - The Monzon Family..................................8 Rabbi Yitzchak Monzon...............................................................8 Rabbi Avraham Leib.....................................................................8 The Grave Structure of Our Matriarch Rachel............................8 The Hurvah Synagogue...........................................................10 Choosing a Bride for Rabbi Avraham Leib Monzon ..................19 Rabbi Yoel Yosef Shimon Shemesh ...........................................20 Avraham Yehuda Leib Monzon.................................................26 Monzon Lithography – The First Stone Press In Jerusalem .........30 -

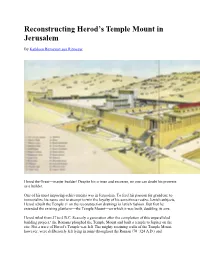

Reconstructing Herod's Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Reconstructing Herod’s Temple Mount in Jerusalem By Kathleen RitmeyerLeen Ritmeyer Herod the Great—master builder! Despite his crimes and excesses, no one can doubt his prowess as a builder. One of his most imposing achievements was in Jerusalem. To feed his passion for grandeur, to immortalize his name and to attempt to win the loyalty of his sometimes restive Jewish subjects, Herod rebuilt the Temple (1 on the reconstruction drawing) in lavish fashion. But first he extended the existing platform—the Temple Mount—on which it was built, doubling its size. Herod ruled from 37 to 4 B.C. Scarcely a generation after the completion of this unparalleled building project,a the Romans ploughed the Temple Mount and built a temple to Jupiter on the site. Not a trace of Herod’s Temple was left. The mighty retaining walls of the Temple Mount, however, were deliberately left lying in ruins throughout the Roman (70–324 A.D.) and Byzantine (324–640 A.D.) periods—testimony to the destruction of the Jewish state. The Islamic period (640–1099) brought further eradication of Herod’s glory. Although the Omayyad caliphs (whose dynasty lasted from 633 to 750) repaired a large breach in the southern wall of the Temple Mount, the entire area of the Mount and its immediate surroundings was covered by an extensive new religio-political complex, built in part from Herodian ashlars that the Romans had toppled. Still later, the Crusaders (1099–1291) erected a city wall in the south that required blocking up the southern gates to the Temple Mount. -

Israel and Judah: 18. Temple Interior and Dedication

Associates for Scriptural Knowledge • P.O. Box 25000, Portland, OR 97298-0990 USA © ASK, March 2019 • All rights reserved • Number 3/19 Telephone: 503 292 4352 • Internet: www.askelm.com • E-Mail: [email protected] How the Siege of Titus Locates the Temple Mount in the City of David by Marilyn Sams, July 2016 Formatted and annotated by David Sielaff, March 2019 This detailed research paper by independent author Marilyn Sams is one of several to follow her 2015 book, The Jerusalem Temple Mount Myth. Her book was inspired by a desire to prove (or disprove) Dr. Ernest Martin’s research in The Temples That Jerusalem Forgot. Ms. Sams wrote a second book in 2017, The Jerusalem Temple Mount: A Compendium of Ancient Descriptions expanding the argument in her first book, itemizing and analyzing 375 ancient descriptions of the Temple, Fort Antonia, and environs, all confirming a Gihon location for God’s Temples.1 Her books and articles greatly advance Dr. Martin’s arguments. David Sielaff, ASK Editor Marilyn Sams: The siege of Titus has been the subject of many books and papers, but always from the false perspective of the Jerusalem Temple Mount’s misidentification.2 The purpose of this paper is to illuminate additional aspects of the siege, in order to show how they cannot reasonably be applied to the current models of the temple and Fort Antonia, but can when the “Temple Mount” is identified as Fort Antonia. Conflicts Between the Rebellious Leaders Prior to the Siege of Titus A clarification of the definition of “Acra” is crucial to understanding the conflicts between John of Gischala and Simon of Giora, two of the rebellious [Jewish] faction leaders, who divided parts of Jerusalem 1 Her second book shows the impossibility of the so-called “Temple Mount” and demonstrate the necessity of a Gihon site of the Temples. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

31295018689751.Pdf (8.512Mb)

^M'-^Ki'm-r- --' •« >i^'?fi O^t LQG The Design for a School of Art 'mi The Depot District Lubbock, Texas Robyn Giuiro^a '^^mX'> m KfiB^i?»5!^ppii|M^|(!f|?s Fall 1999 I^^^S-"* • . .M by Robyn Qulroqa A Thesis Architecture Submitted to the Architecture faculty of the College of Architecture of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment for The Degree of MASTERS OF ARCHITECTURE Jarfcesl White, Dean. College of Architecture December 1999 ii 5 2 a037cQ.L'J> /9 <^ r- •] ^r.^^ wt\' ~^Kitlft ii^ A^^m oj ii N (iW/!>«n#»ij%) 11 J IAB »? s; of IINSSI^ ' 04 THEORY 05 THEORY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES oe BACI^GROUND INFORMATION ON COLLAGE 24 THEORY ISSUES 25 THEORY ISSUE NUMBER ONE 26 THEORY ISSUE NUMBER TWO 27 THEORY ISSUE NUMBER THREE 26 THEORY CASE STUDIES 29 THEORY CASE STUDY NUMBER ONE: THE ANTHENEUM BY RICHARD MEIER THEORY CASE STUDY NUMBER TWO: ADDISON CONFERENCE AND THEATRE CENTRE 33 FACILITY TYPE 34 MISSION STATEMENT 35 ACTIVITY ANALYSIS 37 FACILITY PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS 40 SPATIAL ANALYSIS 56 SPATIAL SUMMARY 60 FACILITY TYPE CASE STUDIES 61 FACILITY TYPE CASE STUDY NUMBER ONE: CENTRE FOR THE VISUAL ARTS BY FRANK GEHRY 67) FAr:il ITY TYPE CASE STUDY NUMBER TWO: ART SCHOOL BY KUOVO & PARTANEN ARCHITECTS 111 OS i|Nii9D^ DESIGN PROCESS SCHEMATIC REVIEW DESIGN DEVELOPMENT COHCEFTONE CONCEPT TWO COHCEFTTHREE DESIGN RESPONSE RESPONSE TO THEORY ISSUES RESPONSE TO FACILITY TYPE PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS RESPONSE TO CONTEXT ISSUES IV -"" IABIH OJ ilNiSSiip 102 DOCUMENTATION 103 Overall Presentation Layout 104 Courtyard Level Plan if: 105 First Floor Plan 106 East and North Elevations 107 West and South Elevations 106 Transverse and Longitudinal Sections 109 Structural Axon 110 Site Plan and Mechanical Flans 111 Interior Perspective 112 Exterior Perspective 113 Mode! Photos 114 Conclusion 115 LIST OF ILLUTRATIONS 125 BIBLIOGRAPHY l£s iHaAgT 'AK I£s fiQABT The theory of artistic collage as an architectural design tool will be used in the design process. -

Boundaries, Barriers, Walls

1 Boundaries, Barriers, Walls Jerusalem’s unique landscape generates a vibrant interplay between natural and built features where continuity and segmentation align with the complexity and volubility that have characterized most of the city’s history. The softness of its hilly contours and the harmony of the gentle colors stand in contrast with its boundar- ies, which serve to define, separate, and segregate buildings, quarters, people, and nations. The Ottoman city walls (seefigure )2 separate the old from the new; the Barrier Wall (see figure 3), Israelis from Palestinians.1 The former serves as a visual reminder of the past, the latter as a concrete expression of the current political conflict. This chapter seeks to examine and better understand the physical realities of the present: how they reflect the past, and how the ancient material remains stimulate memory, conscious knowledge, and unconscious perception. The his- tory of Jerusalem, as it unfolds in its physical forms and multiple temporalities, brings to the surface periods of flourish and decline, of creation and destruction. TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOGRAPHY The topographical features of Jerusalem’s Old City have remained relatively con- stant since antiquity (see figure ).4 Other than the Central Valley (from the time of the first-century historian Josephus also known as the Tyropoeon Valley), which has been largely leveled and developed, most of the city’s elevations, protrusions, and declivities have maintained their approximate proportions from the time the city was first settled. In contrast, the urban fabric and its boundaries have shifted constantly, adjusting to ever-changing demographic, socioeconomic, and political conditions.2 15 Figure 2. -

Politics in the Planning of the Western Wall Plaza

Chapter 3 Politics in the Planning of the Western Wall Plaza The question of how to design and construct the Western Wall plaza arose immediately with the end of the Six-Day War. The total destruction of the Mughrabi Quarter, the empty space created as a result, and the transfer of the Western Wall to the authority of the State of Israel and the Ministry of Religions afforded an unparalleled opportunity to plan and construct the plaza as a site bearing both national and religious meaning. There was general agree- ment that the nondescript, newly created plaza required a process of archi- tectural development. But how was the state to design such an important and significant site to meet the needs of the many worshippers and visitors, one befitting its status as a Jewish holy place and an Israeli symbol? How should the site be rebuilt in order to serve as a place of worship and religious com- munion and simultaneously as a historical and national emblem? The answers to these questions, as we will see below, turned out to be exceedingly complex and sensitive. The indecision regarding the architectural design of the Western Wall became the subject of an incisive and prolonged public and political de- bate in Israel; in it, Israeli and Jewish values, religion and nationality, and past and present all came into conflict. The present chapter focuses on the struggle surrounding the issue of the design and renovation of the Western Wall plaza in the first decades follow- ing the Six-Day War, and analyzes the political forces that put this process in motion. -

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.)

The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 A.D.) Leen Ritmeyer • 08/03/2018 This post was originally published on Leen Ritmeyer’s website Ritmeyer Archaeological Design. It has been republished with permission. Visit the website to learn more about the history of the Temple Mount and follow Ritmeyer Archaeological Design on Facebook. Following on from our previous drawing, the Temple Mount during the Hellenistic and Hasmonean periods, we now examine the Temple Mount during the Herodian period. This was, of course, the Temple that is mentioned in the New Testament. Herod extended the Hasmonean Temple Mount in three directions: north, west and south. At the northwest corner he built the Antonia Fortress and in the south, the magnificent Royal Stoa. In 19 B.C. the master-builder, King Herod the Great, began the most ambitious building project of his life—the rebuilding of the Temple and the Temple Mount in lavish style. To facilitate this, he undertook a further expansion of the Hasmonean Temple Mount by extending it on three sides, to the north, west and south. Today’s Temple Mount boundaries still reflect this enlargement. The cutaway drawing below allows us to recap on the development of the Temple Mount so far: King Solomon built the First Temple on the top of Mount Moriah which is visible in the center of this drawing. This mountain top can be seen today, inside the Islamic Dome of the Rock. King Hezekiah built a square Temple Mount (yellow walls) around the site of the Temple, which he also renewed. -

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museu

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museum Tower of David Herod’s Palace Temple Mount The Temple Mount, in Hebrew: Har HaBáyit, "Mount of the House of God", known to Muslims as the Haram esh-Sharif, "the Noble Sanctuary and the Al Aqsa Compound, is a hill located in the Old City of Jerusalem that for thousands of years has been venerated as a holy site in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike. The present site is a flat plaza surrounded by retaining walls (including the Western Wall) which was built during the reign of Herod the Great for an expansion of the temple. The plaza is dominated by three monumental structures from the early Umayyad period: the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock and the Dome of the Chain, as well as four minarets. Herodian walls and gates, with additions from the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods, cut through the flanks of the Mount. Currently it can be reached through eleven gates, ten reserved for Muslims and one for non-Muslims, with guard posts of Israeli police in the vicinity of each. According to Jewish tradition and scripture, the First Temple was built by King Solomon the son of King David in 957 BCE and destroyed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE – however no substantial archaeological evidence has verified this. The Second Temple was constructed under the auspices of Zerubbabel in 516 BCE and destroyed by the Roman Empire in 70 CE. -

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents In the name of Allah, most compassionate, most merciful Introduction JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<3 Dear Visitor, Mosques JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<<4 Welcome to one of the major Islamic sacred sites and landmarks Domes JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<24 of civilization in Jerusalem, which is considered a holy city in Islam because it is the city of the prophets. They preached of the Minarets JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<30 Messenger of God, Prophet Mohammad (PBUH): Arched Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<32 The Messenger has believed in what was revealed to him from his Lord, and [so have] the believers. All of them have believed in Allah and His angels and Schools JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<36 His books and His messengers, [saying], “We make no distinction between any of His messengers.” And they say, “We hear and we obey. [We seek] Your Corridors JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<44 forgiveness, our Lord, and to You is the [final] destination” (Qur’an 2:285). Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<46 It is also the place where one of Prophet Mohammad’s miracles, the Night Journey (Al-Isra’ wa Al-Mi’raj), took place: Water Sources JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<54 Exalted is He who took His Servant -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr.