Identity, Performance, and Persona in Womenâ•Žs Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

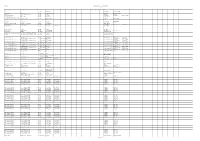

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City

Lahm, Sarah. "'Yas Queen': Postfeminism and Urban Space Oddities in Broad City." Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City. Ed. Stefan L. Brandt and Michael Fuchs. Vienna: LIT Verlag, 2018. 161-177. ISBN 978-3-643-50797-6 (pb). "VAS QUEEN": POSTFEMINISM AND URBAN SPACE ODDITIES IN BROAD CITY SARAH LAHM Broad City's (Comedy Central, since 2014) season one episode "Working Girls" opens with one of the show's most iconic scenes: In the show's typical fashion, the main characters' daily routines are displayed in a split screen, as the scene underline the differ ences between the characters of Abbi and Ilana and the differ ent ways in which they interact with their urban environment. Abbi first bonds with an older man on the subway because they are reading the same book. However, when he tries to make ad vances, she rejects them and gets flipped off. In clear contrast to Abbi's experience during her commute to work, Ilana intrudes on someone else's personal space, as she has fallen asleep on the subway and is leaning (and drooling) on a woman sitting next to her (who does not seem to care). Later in the day, Abbi ends up giving her lunch to a homeless person who sits down next to her on a park bench, thus fitting into her role as the less assertive, more passive of the two main characters. Meanwhile, Ilana does not have lunch at all, but chooses to continue sleeping in the of ficebathroom, in which she smoked a joint earlier in the day. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

'COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List' Debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 P.M.*

What Winter Cold? These Comedians are Bringing the Heat! Check Out the World Premiere of 'COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List' Debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m.* NEW YORK, Nov. 16, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- COMEDY CENTRAL is unleashing a new "Hot List" of its star comics upon the world! See who makes the cut in the World Premiere of "COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List," debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m. With the success of 2009's "Hot List," which included white-hot comedians Aziz Ansari, Donald Glover, Nick Kroll and Whitney Cummings, COMEDY CENTRAL is proving its prophetic prowess yet again by rolling out a bevy of break-through talent that audiences will soon have to reckon with. COMEDY CENTRAL has picked seven of the hottest comedians who have been on a hot streak in the clubs, on the Internet, in films and on television. This year's cream of the comedic crop includes Pete Holmes ("John Oliver's New York Stand-Up Show," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"), Reggie Watts ("Michael & Michael Have Issues"), Chelsea Peretti ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "The Sarah Silverman Program"), Kurt Metzger ("Ugly Americans," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"), Kyle Kinane ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "Last Call with Carson Daly"), Natasha Leggero ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "Ugly Americans," "Last Comic Standing") and Owen Benjamin ("The House Bunny," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"). "COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List" includes interviews with the comedians as well as clips from their various performances and day-in-the-life footage captured with a self-recorded flipcam. Tune in Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m. -

Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 12-2016 Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News Kathy Elrick Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Elrick, Kathy, "Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News" (2016). All Dissertations. 1847. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC FEMINISM: RHETORICAL CRITIQUE IN SATIRICAL NEWS A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Kathy Elrick December 2016 Accepted by Dr. David Blakesley, Committee Chair Dr. Jeff Love Dr. Brandon Turner Dr. Victor J. Vitanza ABSTRACT Ironic Feminism: Rhetorical Critique in Satirical News aims to offer another perspective and style toward feminist theories of public discourse through satire. This study develops a model of ironist feminism to approach limitations of hegemonic language for women and minorities in U.S. public discourse. The model is built upon irony as a mode of perspective, and as a function in language, to ferret out and address political norms in dominant language. In comedy and satire, irony subverts dominant language for a laugh; concepts of irony and its relation to comedy situate the study’s focus on rhetorical contributions in joke telling. How are jokes crafted? Who crafts them? What is the motivation behind crafting them? To expand upon these questions, the study analyzes examples of a select group of popular U.S. -

DACIN SARA Repartitie Aferenta Trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU

DACIN SARA Repartitie aferenta trimestrului III 2019 Straini TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 R11 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 Greg Pruss - Gregory 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Pruss 1000 post Terra After Earth 2013 US M. Night Shyamalan Gary Whitta M. Night Shyamalan 30 de nopti 30 Days of Night: Dark Days 2010 US Ben Ketai Ben Ketai Steve Niles 300-Eroii de la Termopile 300 2006 US Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Zack Snyder Michael B. Gordon 6 moduri de a muri 6 Ways to Die 2015 US Nadeem Soumah Nadeem Soumah 7 prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul / Sapte The Seven Little Foys 1955 US Melville Shavelson Jack Rose Melville Shavelson prichindei cuceresc Broadway-ul A 25-a ora 25th Hour 2002 US Spike Lee David Benioff Elaine Goldsmith- A doua sansa Second Act 2018 US Peter Segal Justin Zackham Thomas A fost o data in Mexic-Desperado 2 Once Upon a Time in Mexico 2003 US Robert Rodriguez Robert Rodriguez A fost odata Curly Once Upon a Time 1944 US Alexander Hall Lewis Meltzer Oscar Saul Irving Fineman A naibii dragoste Crazy, Stupid, Love. 2011 US Glenn Ficarra John Requa Dan Fogelman Abandon - Puzzle psihologic Abandon 2002 US Stephen Gaghan Stephen Gaghan Acasa la coana mare 2 Big Momma's House 2 2006 US John Whitesell Don Rhymer Actiune de recuperare Extraction 2013 US Tony Giglio Tony Giglio Acum sunt 13 Ocean's Thirteen 2007 US Steven Soderbergh Brian Koppelman David Levien Acvila Legiunii a IX-a The Eagle 2011 GB/US Kevin Macdonald Jeremy Brock - ALCS Les aventures extraordinaires d'Adele Blanc- Adele Blanc Sec - Aventurile extraordinare Luc Besson - Sec - The Extraordinary Adventures of Adele 2010 FR/US Luc Besson - SACD/ALCS ale Adelei SACD/ALCS Blanc - Sec Adevarul despre criza Inside Job 2010 US Charles Ferguson Charles Ferguson Chad Beck Adam Bolt Adevarul gol-golut The Ugly Truth 2009 US Robert Luketic Karen McCullah Kirsten Smith Nicole Eastman Lebt wohl, Genossen - Kollaps (1990-1991) - CZ/DE/FR/HU Andrei Nekrasov - Gyoergy Dalos - VG. -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

Liberty City Guidebook

Liberty City Guidebook YOUR GUIDE TO: PLACES ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: • dizziness • eye or muscle twitches • disorientation • any involuntary movement • altered vision • loss of awareness • seizures or convulsion. RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. • Avoid prolonged use of the PLAYSTATION®3 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. • Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Stop using the system immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms: lightheadedness, nausea, or a sensation similar to motion sickness; discomfort or pain in the eyes, ears, hands, arms, or any other part of the body. If the condition persists, consult a doctor.