Is Public Transport Spatially and Temporally Equitable? a Case-Study in South-East Bangalore∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka (Constituted by the Moef, Government of India)

State Level Expert Appraisal Committee (SEAC), Karnataka (Constituted by the MoEF, Government of India) No. KSEAC: MEETING: 2016 Dept. of Ecology and Environment, Karnataka Government Secretariat, Room No. 710, 7th Floor, I Stage, M.S. Building, Bangalore, Date:27.01.2017 Agenda for 177th Meeting of SEAC scheduled to be held on 6th and 7th February 2017 6th February 2017 10.00 AM to 1.30 PM EIA Presentation: 177.1 Expansion and Modification of Sugar factory of capacity from 4000 TCD to 5500 TCD and additional power generation of 15 MW (12 to 27 MW) at Sankonatti,Athani,Belgaum of M/s Krishna Sahakari Sakkare Karkhane Niyamit (KSSKN), Sankonatti Post- 591304, Athani Taluk, Belgaum District (SEIAA 26 IND 2015) 177.2 Expansion & Modification of Residential Apartment Project at Sy.Nos.75, 77/1, 77/2, 77/3, 77/4, 77/7, 78, 78/2, 79, 80, 81/2, 83/2, 83/3, 83/4, 83/5, 83/8, 83/9, 86/2, 86/3, 86/4, 86/7, 86/8, 87/4 of Kannamangala Village, Devanahalli Taluk, Bangalore Rural District of M/s. Ozone Urbana Infra Developers Pvt. Ltd., #38, Ulsoor Road, Bangalore - 560042. (SEIAA 124 CON 2016) Referred back from the Authority: 177.3 Construction of Medical Sciences and Research Center at Sy.No.26 & 27 of Kasavanahalli Village, Varthur Hobli, Bangalore Urban District of M/s. KARNATAKA REDDY JANA SANGHA, #1, Mahayogi Vemana Road, 16th Main, Koramangala, 3rd Block, Bangalore - 560034. (SEIAA 64 CON 2016) Deferred subjects: 177.4 Proposed residential apartment project at Sy. NO. 34/1 and 34/2, Channasandra village, Bidarahalli Hobli, Bengaluru East Taluk, Bengaluru of M/s. -

V-356N Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

V-356N bus time schedule & line map V-356N Kempegowda Bus Station - Chandapura Circle View In Website Mode The V-356N bus line (Kempegowda Bus Station - Chandapura Circle) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandapura Circle: 5:00 PM - 8:00 PM (2) Kempegowda Bus Station: 7:00 PM - 10:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest V-356N bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next V-356N bus arriving. Direction: Chandapura Circle V-356N bus Time Schedule 36 stops Chandapura Circle Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:00 PM - 8:00 PM Kempegowda Bus Station Majestic Platform 6A, Bangalore Tuesday Not Operational Maharani College Wednesday Not Operational Sheshadri Road, Bangalore Thursday Not Operational K.R.Circle Friday Not Operational St Marthas Hospital Corporation Saturday Not Operational Corporation Subbaiah Circle 7th Main Road, Bangalore V-356N bus Info Direction: Chandapura Circle Kh Road Stops: 36 Trip Duration: 52 min Shanthinagara Ttmc Line Summary: Kempegowda Bus Station Majestic, Maharani College, K.R.Circle, St Marthas Hospital Wilson Garden Police Station Corporation, Corporation, Subbaiah Circle, Kh Road, Shanthinagara Ttmc, Wilson Garden Police Station, Wilson Garden 12th Cross Wilson Garden 12th Cross, Lakkasandra, Nimhans Hospital, Bangalore Dairy Circle, Muneshwara 466/1 10th Main, 13th Cross Temple, Jn Of Hosur Road, St John Hospital, Lakkasandra Koramangala Water Tank, Krupanidhi College, Madivala, Rupena Agrahara, Bommanahalli, Garvebhavi Palya, Kudlu -

411D Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

411D bus time schedule & line map 411D Marathahalli Bridge - Chandapura View In Website Mode The 411D bus line (Marathahalli Bridge - Chandapura) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandapura: 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM (2) Marathahalli Bridge: 5:45 AM - 5:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 411D bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 411D bus arriving. Direction: Chandapura 411D bus Time Schedule 30 stops Chandapura Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM Monday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM B.Narayanapura Tuesday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM Mahadevapura Wednesday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM Emc 2 Thursday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM Karthiknagara Friday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM Service Road, Bangalore Saturday 7:10 AM - 7:05 PM Marathhalli Bridge Marathahalli Multiplex 545 1st Floor, CMH Road 411D bus Info Innovative Multiplex Direction: Chandapura 90/4 (1st Floor) Outer Ring Road, Bangalore Stops: 30 Trip Duration: 66 min Kadabisanahalli Line Summary: B.Narayanapura, Mahadevapura, 20/6, Durga Money Tree Outer Ring Road Emc 2, Karthiknagara, Marathhalli Bridge, Marathahalli Multiplex, Innovative Multiplex, New Horizon College Kadabisanahalli, New Horizon College, service road, Bangalore Devarabisanahalli, Cs-Accenture B7 Eco Space, Bellanduru Junction City Light Apartment, Ibbaluru, Devarabisanahalli Agara Junction, Agara/H.S.R, H.S.R B.D.A Complex, Hsr Apartment, Central Silk Board, Rupena Agrahara, Cs-Accenture B7 Eco Space Bommanahalli, Garvebhavi Palya, Kudlu Gate, Singasandra, Hosa Road, P.E.S.I.T. College, Bellanduru Junction City Light Apartment Konappana Agarhara, Electronic City, Hebbagodi, B.T.L.College, Chandapura Ibbaluru 30 Marathahalli - Sarjapur Outer Ring Rd, Iblur Village Agara Junction Agara/H.S.R Srinagar - Kanyakumari Highway, Bangalore H.S.R B.D.A Complex Hsr Apartment Central Silk Board Srinagar - Kanyakumari Highway, Bangalore Rupena Agrahara Bommanahalli Garvebhavi Palya 38/7 Near Krishnappa Reddy Building, Bandepalya Kudlu Gate 52, Hosur Main Rd Singasandra Hosa Road Hosur Road, Bangalore P.E.S.I.T. -

Ramanagara District

Details of Respective area engineers of BESCOM (Row 2 - District name) (Column 10 - Alphabetical order of Areas) District: Ramanagar Sl Zone Circle Division Sub Division O&M Unit Areas No 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Assistant Assistant Superintending Executive Engineer / Name Chief Engineer Name Name Name Executive Name Engineer Engineer Junior Engineer Engineer BRAZ Sri. Siddaraju ramanagara "Sri. Nagarajan chandapura "(EE) 9448234567 94498 41655 Thimmegowda 080-23500117 080-28488780 9448279027 (eechandapura [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] n .in" .in) muniswamy layout Kammasandra ( F-14 Feeder, Electronic city MUSS) bommasandra industrial are 3rd phase bommasandra industrial area 3rd stage near Smt. Jamuna acharya ITI collage padmapriya industrial estate --NPS fa bommasandra village, Concord Wind Rass Appt Ramsagar village heelalige Heelalige Main Road Near "(AEE) 9449865127 BCET Engineering College Chandapura RK Lake Viw, Thimmareddy industrial area old chandapura Vidyanagar, Heelalige grama royal gardenia RS Gardenium Shashidhar M.K aochandapura@gma decathlon Varthur main road Ananthnagar Phase-1 SFS Enclave, Dady's Garden, Golden nest rk city 4th lane neraluru..Dady's Garden, Golden nest ( HT ) VEERA 8277892574 il.com AE Suresh munireddy industrial area, near A2B hotel MR Layout (old chandapura) Banglapete , fortune city noorani masjid Tranquil city Opposite Hebbagodi police SANDRA 8310502355 ANANTHA 1 9449872371, station Infosys colony reliable levendulla house huskur gate hellalige gate royal mist apartment -

356F Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

356F bus time schedule & line map 356F Adusonnahatti Cross - Krishnarajendra Market View In Website Mode The 356F bus line (Adusonnahatti Cross - Krishnarajendra Market) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Adusonnahatti Cross: 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM (2) Krishnarajendra Market: 8:35 AM - 6:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 356F bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 356F bus arriving. Direction: Adusonnahatti Cross 356F bus Time Schedule 35 stops Adusonnahatti Cross Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM Monday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM K.R.Market Tuesday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM Makkala Koota Wednesday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM Basappa Circle Thursday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM Minerva Circle Friday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM Lalbhagh Main Gate Saturday 6:45 AM - 5:10 PM Lalbagh Fort Road, Bangalore Lalbagh Hopcoms Lalbagh Fort Road, Bangalore 356F bus Info 7th Cross Wilson Garden Direction: Adusonnahatti Cross Stops: 35 Lakkasandra Trip Duration: 67 min Line Summary: K.R.Market, Makkala Koota, Nimhans Hospital Basappa Circle, Minerva Circle, Lalbhagh Main Gate, Lalbagh Hopcoms, 7th Cross Wilson Garden, Bangalore Dairy Circle Lakkasandra, Nimhans Hospital, Bangalore Dairy Circle, Muneshwara Temple, Jn Of Hosur Road, St Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore John Hospital, Koramangala Water Tank, Krupanidhi College, Madivala, Rupena Agrahara, Bommanahalli, Muneshwara Temple Garvebhavi Palya, Kudlu Gate, Singasandra, Hosa Road, P.E.S.I.T. College, Konappana Agarhara, Jn Of Hosur Road Electronic City, Veerasandra, Huskur Gate, Hebbagodi, Bommasandra, B.T.L.College, Hennagra St John Hospital Gate, Chandapura, Hale Chandapura, Thirumagondanahalli Cross, Ado Sonnahatti Koramangala Water Tank Krupanidhi College Madivala Rupena Agrahara Bommanahalli Garvebhavi Palya 38/7 Near Krishnappa Reddy Building, Bandepalya Kudlu Gate 52, Hosur Main Rd Singasandra Hosa Road Hosur Road, Bangalore P.E.S.I.T. -

Concorde Royal Sunnyvale

https://www.propertywala.com/concorde-royal-sunnyvale-bangalore Concorde Royal Sunnyvale - Chandapura, Bang… 3 & 4 BHK villas present in Concorde Royal Sunnyvale Concorde Group presents Concorde Royal Sunnyvale with 3 & 4 BHK villas in Chandapura Anekal Road, Bangalore. Project ID : J919000451 Builder: Concorde Group Properties: Independent Houses, Residential Plots / Lands Location: Concorde Royal Sunnyvale, Chandapura, Bangalore - 560081 (Karnataka) Completion Date: Aug, 2015 Status: Started Description Royal Sunnyvale is a world class community of villas which is begin developed by Concorde Group. This group creates a unique project that gives a standard of design, quality and a standard of living. This villas gives all the amenities nearby. Amenities Royal Entrance Beautifully landscaped colorful garden Skating Rink Terrace garden with swimming pool Concealed Storm Water Drains Tre lined arena Jogging Track Children’s Play area Wide Tar Roads Sewerage System with STP Entry lounge Health club (Gym, Aerobics, Sauna, Steam bath, Jacuzzi) Indoor games room (Carom, Cards, Chess) Table tennis Concealed badminton court Parlor 2-3 guest rooms Coffee bar Swimming pool Billiards/ Snooker Squash Creche 50 member party hall Daily needs super market The Concorde Group does its operations with a group of plot developers. The group has a strategic shift into construction of villas and apartments; from that it is transformed and carved an enviable niche in the real estate arena, by offering unmatched living experience through continued quality consciousness. -

Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation

4/17/2011 Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corp… Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation Vajra Route Origin Destination VIA PLACES No. J.P.Nagara PH 2 Majestic (KBS) Corporation, Lalbagh Main Gate, Jayanagara 4th Block VI Kuvempu Nagar Basaveshwara Jayanagar 9th Block, Jayanagar Bus Station, Ashoka Pillar, 25M (BTM Layout) Nagar Corporation,KBS,Central Talkies, Modi Hospital, Basaveshwarnagar BSK 3rd Stg 3rd 45G Majestic (KBS) Cottonpet Hospital, Chamrajpet, Hanumanthanagar, Hoskere Halli Phase Cross,BSK 3rd stafe 3rd phase Shivajinagar Bus 195 Chandra Layout K.R.Circle, Majestic (KBS), Sujatha Talkies, Vijayanagara. Income Station Tax Layout, Chandra Layout Banashankari Stage, Hosakerehalli cross, Monotype, Jayanagar 5th C.V.Raman Block, III BTM Layout, Madivala, Domlur, Indiranagar, Domlur, 201R Srinagara Nagara DRDO Qtrs. C.V. Ramannagar Brigade Maharani's College, Corporation, Lalbagh,Jayanagara Bus Station, 215BM Majestic (KBS) Millennium Oxford Dental College, Puttenahalli, Brigade Mellineium Central Talkies, Malleshwaram, Yeshwanthpura, CMTI, Jalahalli 250I Majestic (KBS) Chikkabanavara Cross, Janapriya Apartments, Chikkabanavara Central Talkies, Yeshwanthpura, Dasarahalli, Makali, 258C Majestic (KBS) Nelamangala Binnamangala, Nelamangala KBS, Central Talkies, Devasandra, Nanjappa 276 Majestic (KBS) Vidyaranyapura Circle,Vidyaranyapura Nanjappa circle, Sadashivanagara Police Station, Maharani's 276G Vidyaranyapura Electronic City College, Cauvery Bhavan,Wilson Garden Police station, Bommanahalli, Kudlu Gate, Electronic city -

360C Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

360C bus time schedule & line map 360C Ballur - Krishnarajendra Market View In Website Mode The 360C bus line (Ballur - Krishnarajendra Market) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ballur: 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM (2) Krishnarajendra Market: 4:50 AM - 5:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 360C bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 360C bus arriving. Direction: Ballur 360C bus Time Schedule 38 stops Ballur Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM Monday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM Krishnarajendra Market Kalasipalya Main Road, Bangalore Tuesday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM Lalbhagh Main Gate Wednesday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM Lalbagh Fort Road, Bangalore Thursday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM Lalbagh Hopcoms Friday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM Lalbagh Fort Road, Bangalore Saturday 6:40 AM - 8:00 PM 7th Cross Wilson Garden Lakkasandra Nimhans Hospital 360C bus Info Direction: Ballur Bangalore Dairy Circle Stops: 38 Bannerghatta Road, Bangalore Trip Duration: 67 min Line Summary: Krishnarajendra Market, Lalbhagh Muneshwara Temple Main Gate, Lalbagh Hopcoms, 7th Cross Wilson Garden, Lakkasandra, Nimhans Hospital, Bangalore Jn Of Hosur Road Dairy Circle, Muneshwara Temple, Jn Of Hosur Road, St John Hospital, Koramangala Water Tank, St John Hospital Krupanidhi College, Madivala, Rupena Agrahara, Bommanahalli, Garvebhavi Palya, Kudlu Gate, Koramangala Water Tank Singasandra, Hosa Road, Konappana Agarhara, Electronic City, Veerasandra, Huskur Gate, Krupanidhi College Hebbagodi, Bommasandra, B.T.L.College, Hennagra Gate, Chandapura, -

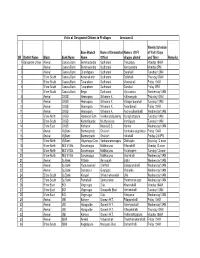

SR District Name Block Bank Name Base Branch Name Name Of

Visits of Designated Officers to FI villages Annexure A Weekly Schedule Base Branch Name of Designated Name/s Of FI of Visit ( Days SR District Name Block Bank Name Name Officer villages alloted and Time) Remarks 1 Bangalore Urban Anekal Canara Bank Bommasandra Sudharani Thirupalya Monday 10AM 2 Anekal Canara Bank Bommasandra Sudharani Veerasandra Monday 2PM 3 Anekal Canara Bank Chandapura Sudharani Banahalli Tuesday 10AM 4 B'lore South Canara Bank Konanakunte Sudharani Gollahalli Thursday10AM 5 B'lore South Canara Bank Tavarekere Sudharani Marenahalli Friday 10AM 6 B'lore South Canara Bank Tavarekere Sudharani Ganakal Friday 2PM 7 B'lore South Canara Bank Begur Sudharani Mylasandra Wednesday10AM 8 Anekal CKGB Hennagara Shivanna K. Hulimangala Thursday10AM 9 Anekal CKGB Hennagara Shivanna K. Maragondanahalli Tuesday 10AM 10 Anekal CKGB Hennagara Shivanna K. Yarandahalli Friday 10AM 11 Anekal CKGB Hennagara Shivanna K. Kachanaikanahalli Wednesday10AM 12 B'lore North CKGB Havanoor Extn. Vivekanandaswamy Kasaghattapura Tuesday 10AM 13 B'lore South CKGB Kumbalagodu Mruthyunjaya Kambipura Tuesday 10AM 14 B'lore East CKGB Kothanur Nataraj B.S. Kannur Wednesday10AM 15 Anekal Vij.Bank Bannerghatta Shailesh Kannaikanaagrahara Friday 10AM 16 Anekal Vij.Bank Bannerghatta Shailesh Hullahalli Freiday 2.30PM 17 B'lore North Vij.Bank Vidyanagar Cros Venkataramanappa Chikkajala Saturday 12 noon 18 B'lore North ING VY.Bk. Sondekoppa Mallikarjuna Kittanahalli Monday 12 noon 19 B'lore North ING VY.Bk. Sondekoppa Mallikarjuna Kadabagere Tuesday 12 noon 20 -

Residential Plot / Land for Sale in Chandapura, Bangalore (P86520333)

https://www.propertywala.com/P86520333 Home » Bangalore Properties » Residential properties for sale in Bangalore » Residential Plots / Lands for sale in Chandapura, Bangalore » Property P86520333 Residential Plot / Land for sale in Chandapura, Bangalore 90 lakhs Freehold SHIVAJYOTHI PROPERTIES In Advertiser Details Chandapura, Bangalore 100, Chandapura, Bangalore - 560081 (Karnataka) Area: 371.61 SqMeters ▾ Transaction: Resale Property Price: 9,000,000 Rate: 24,219 per SqMeter Possession: Immediate/Ready to move Description Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile Welcome to upkar spring fields If you are one of those who wants to live away from the hustle-Bustle of the city, upkar spring field is your Pictures dream home. With huge sites, spring fields gives you the opportunity to build your own mansion. Every plot is surrounded by sprawling landscapes and magnificent views. The advantage of living in large plotted layouts gives you a sense of security, community and well-Being. The gated community offers reat connectivity to the surrounding industrial areas of bommanahalli, jigani, electronic city and the sipcot industrial area in hosur, tamil nadu. The ideal location of the property makes it close to the city yet away from it. It is ideal for those looking for affordable luxury. When you call, don't forget to mention that you saw this ad on PropertyWala.com. Features Other features Super Area: 371.61 sq.m. Freehold ownership North Facing Immediate posession Gated Community Location * Location may be approximate Landmarks Nearby Localities Chandapura Circle, KHB Surya City, Bommasandra, Iggalur, Neraluru, Daadys Gaarden Layout, Marsur, Bommasandra Industrial Area * All distances are approximate Locality Reviews Chandapura, Bangalore Well developed area. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

Anekal Bar Association : Anekal Taluk : Anekal District : Bengaluru

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : ANEKAL BAR ASSOCIATION : ANEKAL TALUK : ANEKAL DISTRICT : BENGALURU SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE CHANDRA REDDY N KAR/621/84 S/O NARASIMHA REDDY 1 NO.4/127 OPP COURT BUILDING OLD PWD ODDICE ROAD TOWN URBAN ANEKAL BENGALURU 562 106 SAMPATH KUMAR S L KAR/90/87 2 S/O S R LAKSHMANA REDDY BEHIND POLICE STATION, SARJAPUR ANEKAL BENGALURU SREEKANTA SASTRY.C.N. KAR/393/87 3 S/O NARASHIMHA SASTRY C S NO. 41/1, OFFICE ROAD, OPP: GOVT HOSPITAL, ANEKAL BENGALURU 562 106 NARAYANA SWAMY C. KAR/217/90 4 S/O CHINNASWAMY REDDY NO 98/54, G S PALYA, ELECTRONIC CITY ANEKAL BENGALURU 1/27 3/17/2018 RAMESHA R. KAR/234/90 5 S/O ramaiha MARAGONDANAHALLI, HULIMANGALA POST ANEKAL BENGALURU 562 106 MUNI REDDY KAR/814/90 6 S/O RAMAREDDY BANAHALLI (VIA) CHANDAPURA POST ANEKAL BENGALURU 560099 SRINIVASA REDDY A.M. KAR/804/91 S/O A M SRINIVASA REDDY 7 ALLI BOMMASANDRA, MUTHANAHALLI POST . BOMMASANDRA ANEKAL BENGALURU PAVIN SHANTA BASAPPA KAR/966/91 D/O SHASHIDHAR P. 8 NO 217 1ST FLOOR 6TMAIN 4TH CROSS 4THCROSS NRUPATHUGA NAGAR J.PNAGAR 7TH PHASE KOTHNUR . ANEKAL BENGALURU VIJAYA KUMAR C. KAR/260/92 S/O CHODAPPA 9 NEAR S V M SCHOOL ,MARUTHI LAYOUT, WARD NO 9 ANEKAL BENGALURU 2/27 3/17/2018 ASHOK KUMAR L.G. KAR/352/92 S/O GOPALAIAH 10 1 ST FLOOR , G.M NARAYANA REDDY, LAYOUT ELECTRONIC, CITY PHASE-2 ANEKAL BENGALURU 560 011 MAHADEVAPPA M.