Relationships Between Organisational Culture and Human Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Culture and Organizational Change- a Study on a Large Pharmaceutical Company in Bangladesh

Asian Business Review, Volume 4, Number 2/2014 (Issue 8) ISSN 2304-2613 (Print); ISSN 2305-8730 (Online) 0 Corporate Culture and Organizational Change- a Study on a Large Pharmaceutical Company in Bangladesh S.M. Rezaul Ahsan Senior Manager, Organization Development, The ACME Laboratories Ltd, Dhaka, BANGLADESH ABSTRACT This paper investigates the relationship between corporate culture and attitudes toward organizational change from the perspectives of a large pharmaceutical company in Bangladesh. A structured questionnaire was developed on the basis of the competing values framework of culture typology of Cameron and Quinn (2006) and a study of Justina Simon (June 2012), which was distributed to the 55 staff members of the company. The result shows that there is a significant relationship between corporate culture and organizational change. The study reveals that the organization has adopted all four types of organizational culture and the dominant existing organizational culture is the hierarchy culture. The study also shows that the resistance to change is a function of organizational culture. The implications of the study are also discussed. Key Words: Organizational Culture, Organizational Change, Resistance to change, Change Management JEL Classification Code: G39 INTRODUCTION Corporate culture is a popular and versatile concept in investigate the impact of organizational culture on C the field of organizational behavior and has been organizational change. identified as an influential factor affecting the success There has been significant research in the literature to and failure of organizational change efforts. Culture can explore the impact of organizational culture on both help and hinder the change process; be both a blessing organizational change. -

Building a High Performance Culture: a Fresh Look At

Building a High-Performance Culture: A Fresh Look at Performance Management This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM©). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2012 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. Selection of report topics, treatment of issues, interpretation and other editorial decisions for the Effective Practice Guidelines series are handled by SHRM Foundation staff and the report authors. Report sponsors may review the content prior to publication and provide input along with other reviewers; however, the SHRM Foundation retains final editorial control over the reports. -

Su Ppo R T D O Cu M En T

v T Structures and cultures: A review of the literature Support document 2 EN BERWYN CLAYTON M VICTORIA UNIVERSITY THEA FISHER CANBERRA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ROGER HARRIS CU UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA ANDREA BATEMAN BATEMAN & GILES PTY LTD O MIKE BROWN UNIVERSITY OF BALLARAT D This document was produced by the author(s) based on their research for the report A study in difference: Structures and cultures in registered training organisations, and is an added resource for T further information. The report is available on NCVER’s website: <http://www.ncver.edu.au> R O The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government, state and territory governments or NCVER. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the P author(s). © Australian Government, 2008 P This work has been produced by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) on behalf of the Australian Government and state and territory governments U with funding provided through the Australian Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. Apart from any use permitted under the CopyrightAct 1968, no S part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Requests should be made to NCVER. Contents Contents 2 Tables and figures 3 A review of the literature 4 Section 1: Organisational structure 4 Section 2: Organisational culture 21 Section 3: Structures and cultures – a relationship 38 References 41 Appendix 1: Transmission -

How Does Organizational Culture Impact Intention to Use Customer Relationship Management Amongst Employees?

How does Organizational Culture Impact Intention to use Customer Relationship Management Amongst Employees? Fredrik Vikström Industrial and Management Engineering, masters level 2016 Luleå University of Technology Department of Business Administration, Technology and Social Sciences Does organizational culture impact Customer relationship management adoption within B2B companies? How does organizational culture impact intention to use Customer relationship management amongst employees? Fredrik Vikström VT-2016 Fredrik Vikström Civil engineering Industrial and Management engineering – Industrial marketing Luleå University of Technology Department of Business, Administration, Technology and Social sciences Preface This master thesis is the final step towards attaining my degree in the five year master programme Industrial and Management engineering at Luleå University of Technology. It has been an incredible learning experience lined with tough times that have kept me on my toes throughout. First off I want to thank my supervisor at the company where I completed my placement, Seleena Creedon, whom has contributed with valuable input and guidance throughout the length of the thesis. I would also like to thank Joseph Vella for his continuous and helpful thoughts which have kept me on the right path and provided me with an academic perspective. Lastly I want to thank all the people who have provided helpful thoughts, my friends, and also those who have provided challenge throughout the seminars. May 27th 2016 Fredrik Vikström Abstract Course: Master thesis in industrial and management engineering, industrial marketing, MSc Civil Engineering Author: Fredrik Vikström Title: How organisational culture impacts intention to use CRM Tutor: Joseph Vella Purpose: The aim of this thesis is to elaborate on if organisational culture has an impact on the intention to use a CRM system. -

Mckinsey Quarterly 2015 Number 4.Pdf

2015 Number 4 Copyright © 2015 McKinsey & Company. All rights reserved. Published since 1964 by McKinsey & Company, 55 East 52nd Street, New York, New York 10022. Cover illustration by Vasava McKinsey Quarterly meets the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) chain-of- custody standards. The paper used in the Quarterly is certified as being produced in an environ- mentally responsible, socially beneficial, and economi- cally viable way. Printed in the United States of America. 2015 Number 4 This Quarter It’s almost a truism these days to say that modern corporations must be agile. The pace of industry disruption arising from the digital revolution, combined with nimble, new competitors—including many from emerging markets—have raised the cost of complacency and rigidity. But what does it mean to achieve agility? This issue’s cover package tries to answer that question, starting with intriguing new McKinsey research. Using data from McKinsey’s Organizational Health Index, Michael Bazigos, Aaron De Smet, and Chris Gagnon show how organizations that combine speed with stability are far likelier to be healthy than companies that simply move fast. The utility sector is a striking example of one industry that needs to combine flexibility and stability. Although digital competitors, new data-based business models, and renewable-energy sources are changing the landscape in certain markets, the industry’s sprawl- ing base of heavy assets remains core to its future. Sven Heiligtag and his colleagues Dominik Luczak and Eckart Windhagen describe how a number of leading utilities are trying to straddle these two worlds, suggesting some lessons for companies in other sectors. -

Law and Human Resources

Law and Human Resources Cloud Campus Deakin University is ranked in the top 2% of universities worldwide across the three major international university rankings1 and in the top 50 universities under 50. Deakin University Deakin Law School We are ranked 5 stars for world-class facilities, research and Deakin Law School (DLS) is located in Melbourne – the world’s teaching, as well as employability, innovation and inclusiveness most liveable city for six years in a row and home to a global under the latest Times Higher Education Australian legal market. We have a reputation for excellence in research Employability Rankings. With internationally recognised – staff are leading experts in corporate law, sentencing, health quality of research and teaching, Deakin is now ranked 214 law, Big Data, commercial law, IP and natural resources – and in the prestigious Academic Ranking of World Universities teaching. (ARWU). Ranked no. 3 in Australia for graduate employability, our course curriculum integrates real-world expertise with DLS is ranked no. 53 on the SSRN Top 500 International practical skills to give our students a competitive edge1. Law Schools, between no. 100–150 on QS World University Rankings and between no. 76–100 on the ARWU and Shanghai Deakin is one of the largest universities in Australia, with over rankings2. 52 000 course enrolments and more than 3700 staff. Despite this size, for the past seven years, we have been ranked no. 1 We pride ourselves on delivering a high quality educational in Victoria for student satisfaction, attesting to the value that experience and students are our primary focus. -

City of Laguna Niguel Job Description HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGER

City of Laguna Niguel Job Description HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGER Executive and Management Group FLSA: Exempt DEFINITION To direct, manage, supervise, administer and coordinate human resources activities and operations for the City including recruitment, selection, benefits administration, classification and compensation, worker's compensation, training, employee relations, employee safety, risk management and labor negotiations; to coordinate assigned activities with other divisions, departments and outside agencies; and to provide highly responsible and complex administrative and management support to the City Manager and Assistant City Manager. EXAMPLES OF IMPORTANT DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Important responsibilities and duties may include, but are not limited to, the following: Plan, coordinate administer and supervise programs and services for assigned human resources services and activities including recruitment, selection, benefits administration, and classification and compensation, worker's compensation, training, employee relations, employee safety, and labor negotiations. Manage and participate in the development and implementation of goals, objectives, policies and priorities for assigned programs; recommends and administers policies and procedures. Negotiate labor agreements with associations and resolves sensitive and controversial issues in the course of managing the responsibility for all human resources services and activities. Monitor and evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of service delivery policies, practices, methods and procedures; make recommendations for improvement. Plan, direct, coordinate and review the work plan for staff, assigns work activities, projects and programs; review and evaluate work products, methods and procedures; meet with staff to identify and resolve problems. Coordinate the recruitment and selection process; screen applicants and list job candidate qualifications; recommend eligible candidates for examination or interview; coordinate the oral board and participates in the interview process. -

Procurement Talent Management: Exceptional Outcomes Require Exceptional People

Procurement talent management: Exceptional outcomes require exceptional people Over the past decade, the people behind the relatively Amid all this activity, something is still missing. Other than vague label “procurement function” have collectively put the imperative to secure executive buy-in, the individuals billions of dollars into software, transformation programs, who perform these roles are rarely mentioned in these and third-party services. The goals of this spending have initiatives, instead being described generally as a team, unit been noble—improve efficiency and enhance capabilities or function. to support objectives such as better M&A outcomes, globally adaptable supply chains, regulatory compliance, Where does human capital—the talent—fit into a new and and brand and product stewardship. improved procurement area? By redefining the intersection of human capital and procurement, and recognizing that As procurement has worked toward these goals, it has individuals do the work, it’s possible for organizations to established a core savings foundation built on spending change the dynamic following a four-step process: visibility and awareness, first-wave sourcing opportunities • Plan and design a procurement talent structure such as better bidding, implementation of strategic • Attract and orient new talent sourcing processes, and compliance tracking. • Manage and develop the skills of existing talent • Retain talent Now, top-performing procurement functions are evolving into service providers to the business. They help enable Through this process, companies can identify and cultivate global capabilities and align with other enterprise areas exceptional people to drive both the procurement function in sourcing, savings, and risk management efforts. and the broader business to higher performance levels. -

Weavers Way Human Resources Assistant Weavers Way Co-Op Is

Weavers Way Human Resources Assistant Weavers Way Co-op is looking for an energetic, creative, and experienced individual to join our Human Resources Department. With our plans to expand, we are looking for someone to grow with the organization. The HR Assistant will be responsible for helping in the day-to-day operations of running the department. Starting off as a part-time position, there is potential for full time work as we move closer to opening our third store. The scope of responsibilities for the position at part time includes, but is not limited to: • Benefits Administration – Provide benefits information to employees, process enrollments, terminations, changes, and billing. Ensure deductions are in the payroll system. • Retirement Plan Administration – Provide information on the co-ops retirement plan to all eligible employees, process payroll deductions, and work with Third Party Administrator to process paperwork and Compliance. • Payroll – Enter all newly hired staff, submit payroll memo to Finance on a bi- weekly basis, update pay rates, withholdings, garnishments, etc., as needed. • Orientation and On-Boarding – Complete new hire paperwork with staff, ensure new employees receive information about policies and procedures, and set up/conduct new hire orientations on a monthly basis. • Record Keeping and Personnel Management – Ensure files are stored and retained as required under law. • Labor Law Compliance – Have a fundamental understanding of all applicable labor laws, understand and comply with labor law in all matters related to applicant screening, hiring, etc. This position requires adaptability, a high level of customer service for all internal customers, and the ability to communicate with various personality styles. -

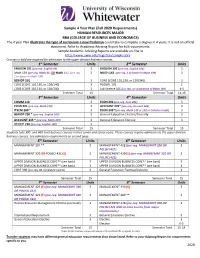

(Fall 2020 Requirements) HUMAN RESOURCES MAJOR

Sample 4 Year Plan (Fall 2020 Requirements) HUMAN RESOURCES MAJOR BBA (COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS) The 4 year Plan illustrates the type of curriculum a new freshman could take to complete a degree in 4 years; it is not an official document. Refer to Academic Advising Report for full requirements. Sample Academic Advising Reports are available on-line at http://www.uww.edu/registrar/sample-aars Courses in bold are required for admission to the upper division business courses. 1st Semester Units 2nd Semester Units ENGLISH 101 (pre-req. English 90) 3 ENGLISH 102 (pre-req. English 101) 3 Math 139 (pre req. Math 41) OR Math 143 (pre req. 3 MATH 143 (pre req. C or better in Math 139) 3 C or better in Math 139) BEINDP 101 3 CORE (CORE 110,130, or 120/140) 3 CORE (CORE 110,130, or 120/140) 3 PEGNRL 192 1 CORE (CORE 110,130, or 120/140) 3 Lab Science (GL) (co req. or completion of Math 139) 4-5 Semester Total 15 Semester Total 14-15 3rd Semester Units 4th Semester Units COMM 110 3 ECON 202 (pre-req. Econ 201) 3 ECON 201 (pre-req. Math 139) 3 ACCOUNT 249* (pre-req. Account 244) 3 ITSCM 280 * 3 ECON 245*(pre-req. Math 143 or 152 or Calculus credit) 3 BEINDP 290 * (pre-req. English 102) 2 General Education Elective/Diversity 3 ACCOUNT 244 * (pre-req. Math 139) 3 General Education Elective 3 BEINDP 288 (pre-req. English 102) 1 Semester Total 15 Semester Total 15 Students take 300- and 400-level business courses in their junior and senior years. -

Office of Human Resources HR Business Partner - LA3154 THIS IS a PUBLIC DOCUMENT

Office of Human Resources HR Business Partner - LA3154 THIS IS A PUBLIC DOCUMENT General Statement of Duties Performs a variety of intermediate level professional work in human resources functions related to employee relations, performance management, workforce readiness, engagement, classification and compensation, dispute resolution, recruitment support and separation. Interprets and explains human resources law, career service rules, administrative regulations, memoranda of understanding, the city ordinances, and other human resources policies and procedures to supervisors and employees. Provides analysis, advice and counsel to managers, supervisors, and employees regarding human resources matters and processes to ensure compliance with the rules, policies, and procedures. Consults with City Attorney’s Office concerning employee relations and dispute resolution items and disciplinary/grievance processes to ensure compliance with the rules, policies, and procedures. Distinguishing Characteristics This class is part of the Human Resources Business Partner classification series. This series encompasses the following job classifications in increasing level of responsibility and scope: Human Resources Business Partner Associate, Human Resources Business Partner, and Human Resources Business Partner Senior. Level of Supervision Exercised None Essential Duties Leads the resolution of disputes and develops solutions to problems between employees and supervisors or managers using a variety of resolution approaches. Develops a project plan, -

Transforming Bureaucracies: Institutionalising Participation and People Centred Processes in Natural Resource Management- an Annotated Bibliography

Transforming Bureaucracies: Institutionalising participation and people centred processes in natural resource management- an annotated bibliography This Annotated Bibliography has been prepared as a collaborative effort involving, in alphabetical order, the following authors: Vanessa Bainbridge Stephanie Foerster Katherine Pasteur Michel Pimbert (Co-ordinator) Garett Pratt Iliana Yaschine Arroyo 2 Table of contents Table of contents..........................................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................................4 Introduction..................................................................................................................................................5 Theories of organisational change for participation ...................................................................................8 Towards learning organisations.................................................................................................................12 Gender and organisational change.............................................................................................................16 Transforming environmental knowledge and organisational cultures ....................................................19 Nurturing enabling attitudes and behaviour..............................................................................................22