Albany in the Life Trajectory of Robert H. Jackson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Officers and Alumni of Rutgers College

* o * ^^ •^^^^- ^^-9^- A <i " c ^ <^ - « O .^1 * "^ ^ "^ • Ellis'* -^^ "^ -vMW* ^ • * ^ ^^ > ->^ O^ ' o N o . .v^ .>^«fiv.. ^^^^^^^ _.^y^..^ ^^ -*v^^ ^'\°mf-\^^'\ \^° /\. l^^.-" ,-^^\ ^^: -ov- : ^^--^ .-^^^ \ -^ «7 ^^ =! ' -^^ "'T^s- ,**^ .'i^ %"'*-< ,*^ .0 : "SOL JUSTITI/E ET OCCIDENTEM ILLUSTRA." CATALOGUE ^^^^ OFFICERS AND ALUMNI RUTGEES COLLEGE (ORIGINALLY QUEEN'S COLLEGE) IlSr NEW BRUJSrSWICK, N. J., 1770 TO 1885. coup\\.to ax \R\l\nG> S-^ROUG upsoh. k.\a., C\.NSS OP \88\, UBR^P,\^H 0? THP. COLLtGit. TRENTON, N. J. John L. Murphy, Printer. 1885. w <cr <<«^ U]) ^-] ?i 4i6o?' ABBREVIATIONS L. S. Law School. M. Medical Department. M. C. Medical College. N. B. New Brunswick, N. J. Surgeons. P. and S. Physicians and America. R. C. A. Reformed Church in R. D. Reformed, Dutch. S.T.P. Professor of Sacred Theology. U. P. United Presbyterian. U. S. N. United States Navy. w. c. Without charge. NOTES. the decease of the person. 1. The asterisk (*) indicates indicates that the address has not been 2. The interrogation (?) verified. conferred by the College, which has 3. The list of Honorary Degrees omitted from usually appeared in this series of Catalogues, is has not been this edition, as the necessary correspondence this pamphlet. completed at the time set for the publication of COMPILER'S NOTICE. respecting every After diligent efforts to secure full information knowledge in many name in this Catalogue, the compiler finds his calls upon every one inter- cases still imperfect. He most earnestly correcting any errors, by ested, to aid in completing the record, and in the Librarian sending specific notice of the same, at an early day, to Catalogue may be as of the College, so that the next issue of the accurate as possible. -

Albany in the Life Trajectory of Robert H. Jackson

ALBANY IN THE LIFE TRAJECTORY OF ROBERT H. JACKSON John Q. Barrett* We recall Supreme Court Justice and Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Houghwout Jackson (1892-1954) for many reasons, but certainly a leading one is the striking contrast between his humble origins and his exalted destinations. Jackson's life began literally in the deep woods, on a family farm in the gorgeous rural isolation of Spring Creek Township in northwestern Pennsylvania's Warren County. He spent his boyhood and obtained his basic public school education in Frewsburg, a small town in southwestern New York State. While still a teenager, Jackson spent one additional year as a high school student in nearby Jamestown, New York, but he never received a day of college education. He prepared to become a lawyer principally by working as an apprentice for two years in a Jamestown law office. From that background, Robert Jackson rose to make big marks very big marks--on the biggest stages of his time, and in history. As a young lawyer, he became a great success in twenty years of private practice while also developing an identity, and some * Professor of Law, St. John's University School of Law, New York City, and Elizabeth S. Lenna Fellow, Robert H. Jackson Center, Jamestown, New York (www.roberthjackson.org). Copyright© 2005 by John Q. Barrett, all rights reserved. This article grows out of my November 15, 2004, keynote lecture at Albany Law School's evening program paying tribute to its alumnus Robert H. Jackson fifty years after the end of his momentous life. I am very grateful to Allen J. -

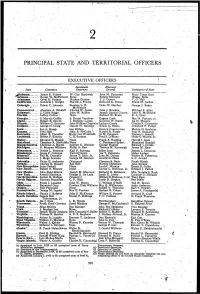

State and Territorial Officers

r Mf-.. 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE- OFFICERS • . \. Lieutenant Attorneys - Siaie Governors Governors General Secretaries of State ^labama James E. Folsom W. Guy Hardwick John M. Patterson Mary Texas Hurt /Tu-izona. •. Ernest W. McFarland None Robert Morrison Wesley Bolin Arkansas •. Orval E. Faubus Nathan Gordon T.J.Gentry C.G.Hall .California Goodwin J. Knight Harold J. Powers Edmund G. Brown Frank M. Jordan Colorajlo Edwin C. Johnson Stephen L. R. Duke W. Dunbar George J. Baker * McNichols Connecticut... Abraham A. Ribidoff Charles W. Jewett John J. Bracken Mildred P. Allen Delaware J. Caleb Boggs John W. Rollins Joseph Donald Craven John N. McDowell Florida LeRoy Collins <'• - None Richaid W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia S, Marvin Griffin S. Ernest Vandiver Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. Idaho Robert E. Smylie J. Berkeley Larseri • Graydon W. Smith Ira H. Masters Illlnoia ). William G. Stratton John William Chapman Latham Castle Charles F. Carpentier Indiana George N. Craig Harold W. Handlpy Edwin K. Steers Crawford F.Parker Iowa Leo A. Hoegh Leo Elthon i, . Dayton Countryman Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas. Fred Hall • John B. McCuish ^\ Harold R. Fatzer Paul R. Shanahan Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Harry Lee Waterfield Jo M. Ferguson Thelma L. Stovall Louisiana., i... Robert F. Kennon C. E. Barham FredS. LeBlanc Wade 0. Martin, Jr. Maine.. Edmund S. Muskie None Frank Fi Harding Harold I. Goss Maryland...;.. Theodore R. McKeldinNone C. Ferdinand Siybert Blanchard Randall Massachusetts. Christian A. Herter Sumner G. Whittier George Fingold Edward J. Cronin'/ JVflchiitan G. Mennen Williams Pliilip A. Hart Thomas M. -

The City Record. � Vol

THE CITY RECORD. VOL. XXXVI. NEW YORK, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 19o8. NUMBER I0815. THE CITY RECORD, Thursday, December 3-2:30 p. m.—Room 31o.—Case No. I000.—LONG ISLAND R. R. Co.—"Proposed deflection of a part of Atlantic Avenue and reloca- tion of the west bound platform at East New York."—Commissioner OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK McCarroll. Published Under Authority of Section 1526, Greater New York Charter, by the 2:30 p. m.—Commissioner Maltbie's Room.—Case No. 1002 under Order BOARD OF CITY RECORD. No, 615.—METROPOLITAN STREET RAILWAY Co.—"Operation of cars on 116th Street."—Commissioner Maltbie. GEORGE B. McCLELLAN, MAYOR Friday, December 4-2 p. m.—Room 305.—Order No. I2I.—INTERROROUGH RAPID TRAN- FRANCIS B. PENDLETON, CORPORATION CouNStn.. HERMAN A. METZ, COMPTEOLLZ . SIT Co.—"Block Signal System—subway local tracks."—Chairman Willcox. PATRICK J. TRACY, SUPERVI9olf. 3 p. m.—Room 305.—Order No. 784.—Public Hearing.—"Proposition of Published daily, at 9 a. m., except legal holidays. Amsterdam Corporation (W. J. Wilgus) for freight subway."—Whole Commission. Subscription, $9.3o per year, exclusive of supplements. Three cents a copy. SUPPLEMENTS: Civil List (containing names, salaries, etc., of the city employees), as cents; Regular meetings of the Commission are held every Tuesday and Friday at 51.30 Official Canvass of Votes, io cents; Registry and Enrollment Lists, s cents each assembly district; a. m. Law Department and Finance Department supplements, to cents each; Annual Assessed Valuation of Real Estate, 25 cents each section. Published at Room 2, City Hall (north side), New York City. -

Alumni and Students of Rutgers College

Li3 4752. .5 1914- W:\^"^^ f>^ 4 Alumni and Students of Rutgers College 1 766-1 91 Alumni and Students of Rutgers College (originally queen's college) I A I PRINTED FOR THE ASSOCIATION OF THE ALUMNI OF RUTGERS COLLEGE JUNE I9I4 $2- U^1 .5 1^ This catalogue of Alumni and Students was prepared and published by the Association of the Alumni of Rutgers College, under the direc- tion of the Registrar of the College. It is earnestly requested that corrections of any sort, especially in addresses, be communicated to the Registrar promptly. The prefixed * indicates death. This line r following the list of the alumni of the several classes indicates that the students whose names follow after it pursued special or short courses of study with these classes, but did not receive the Bachelor's degree. Qirr '^C COLLCO« .** ', M'Aft 27 1915 — ALUMNI AND STUDENTS OF RUTGERS (ORIGINALLY QUEEN'S) COLLEGE 1771-1775 *David Annan, A.M., Rev., Michael Best, *John Bogart, *Peter Kimble, Matthew Leydt, Rev., Abraham Schenck, Henry Harris Schenck, Jr., M.D., John H. Schenck, James Schureman, John Stagg, Isaac Stoutenburgh, Isaac Vredenburgh, John Wall, 1776 Simeon De Witt, A.M., 1777-1779 1780 Jeremiah Smith, LL.D., Simeon Van Arsdalen, John W. Bray, * Courtlandt, * Remsen, Stewart, * — i Van Wyck, 1781 1782 Timothy Blauvelt, Rev., William Crooke, A.M., Peter Leydt, Rev., Samuel Vickers, RUTGERS COLLEGE 1783-1793 1783 Isaac Blauvelt, A.M., Rev., Michael Henry, Pierre Van Cortlandt, A.M., LL.D., John M. Van Harlingen, A.M., Rev., 1784-1786 1787 Abraham Van Home, A.M., Rev., 1788 Walter Cole, A.M., Alpheus Freeman, A.M., Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh, Jr., A.M., John Frelinghuysen Jackson, A.M., Rev., 1789 Methuselah Baldwin, A.M., Rev., Abraham Blauvelt, A.M., John J. -

Press & Sun-Bulletin, Binghamton, NY, July 14, 2009

Press & Sun-Bulletin, Binghamton, NY, July 14, 2009 Ravitch appointment heads to court: Paterson insists The debate among lawyers, constitutional ex- naming lieutenant gov. was legal perts and Paterson is centered on interpretations of By Joseph Spector the state constitution and the public officers’ law. Paterson and those who support his position point to section 43 of the public officers’ law. It ALBANY — Since 1892, there have been 10 vacan- states, in part, that when a vacancy arises midterm in cies in the office of lieutenant governor. Never has a an elective office without a clear provision to fill the governor sought to fill the vacancy by appointment post, “the governor shall appoint a person to execute — until last week. the duties thereof until the vacancy shall be filled by Gov. David Paterson’s move to unilaterally fill an election.” the position is challenging the reach of his office and They interpret that to mean that Paterson can is expected to eventually be heard by the state’s high- fill the lieutenant-governor vacancy. est Court of Appeals. “There’s enough language in the constitution Paterson last Wednesday picked Richard and the statutes to support the governor’s actions,” Ravitch, former head of the Metropolitan Transpor- said Richard Briffault, a professor of legislation at tation Authority, as second-in-command amid the Columbia Law School and vice chairman of Citizens month-long leadership fight in the Senate. Union, an advocacy group that recommended Pater- Without a lieutenant governor, the Senate presi- son fill the position. He is also advising Paterson on dent would succeed the governor. -

Official New York, from Cleveland to Hughes

^^ '^W-^ OFFICIAL N E W YORK FROM CLEVELAND TO HUGHES IN FOUR VOLUMES Editor CHARLES ELLIOTT FITCH, L. H. D. ^ VOLUME II HURD PUBLISHING COMPANY NEW YORK AND BUFFALO 1911 ,...,',,.. 4 ».»),**.»*. 1 > ) trt<^ > 'J Copyright, 1911, by HURD PUBLISHING COMPANY ilEE ADVISORY COMMITTEE Joseph H. Choate, LL.D.,D.C.L. Hon. John Woodward, LL.D. James S. Sherman, LL.D. De Alva S. Alexander, LL. D. Hon. Cornelius N. Bliss Henry W. Hill, LL. D. Horace Porter, LL.D. William C. Morey, LL.D. Andrew D. White, LL.D.,D.C.L. Pliny T. Sexton, LL.D. David J. Hill, LL.D. M. Woolsey Stryker, D.D.,LL.D. Chauncey M. Depew, LL. D. Charles S. Symonds Hon. Horace White Hon. J. Bloat Fassett Charles Andrews, LL. D. Hon. John B. Stanchfield A. Judd Northrup, LL. D. Morgan J. O'Brien, LL.D. T. Guilford Smith, LL.D. Hon. William F. Sheehan Daniel Beach, LL. D. Hon. S. N. D. North CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAGE Governor 13 CHAPTER n Lieutenant Governor 17 CHAPTER III Secretary of State 21 CHAPTER IV Comptroller 27 CHAPTER V State Treasurer 31 CHAPTER VI Attorney General 35 CHAPTER VII State Engineer and Surveyor 39 CHAPTER VIII Education Department 43 CHAPTER IX Origin and Construction of the Barge Canals . 89 CHAPTER X Banking Dkpartment 131 CHAPTER XI Insurance Depaht:ment 151 CHAPTER XII PAGE Superintendent of Public Works .... 163 CHAPTER XIII State Prisons 177 CHAPTER XIV State Charities 187 CHAPTER XV Railroad Commission 209 CHAPTER XVI Public Service Commissions 211 CHAPTER XVII Civil Service Commission 223 CHAPTER XVIII State Commission in Lunacy 229 CHAPTER XIX State Tax Commission 239 CHAPTER XX Miscellaneous ...