Spiritual Vegetarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Opportunities of Frugality in the Post-Corona Era

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Herstatt, Cornelius; Tiwari, Rajnish Working Paper Opportunities of frugality in the post-Corona era Working Paper, No. 110 Provided in Cooperation with: Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute for Technology and Innovation Management Suggested Citation: Herstatt, Cornelius; Tiwari, Rajnish (2020) : Opportunities of frugality in the post-Corona era, Working Paper, No. 110, Hamburg University of Technology (TUHH), Institute for Technology and Innovation Management (TIM), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/220088 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

The Practice of Fasting After Midday in Contemporary Chinese Nunneries

The Practice of Fasting after Midday in Contemporary Chinese Nunneries Tzu-Lung Chiu University of Ghent According to monastic disciplinary texts, Buddhist monastic members are prohibited from eating solid food after midday. This rule has given rise to much debate, past and present, particularly between Mahāyāna and Theravāda Buddhist communities. This article explores Chinese Buddhist nuns’ attitudes toward the rule about not eating after noon, and its enforcement in contemporary monastic institutions in Taiwan and Mainland China. It goes on to investigate the external factors that may have influenced the way the rule is observed, and brings to light a diversity of opinions on the applicability of the rule as it has been shaped by socio- cultural contexts, including nuns’ adaptation to the locals’ ethos in today’s Taiwan and Mainland China. Introduction Food plays a pivotal role in the life of every human being, as the medium for the body’s basic needs and health, and is closely intertwined with most other aspects of living. As aptly put by Roel Sterckx (2005:1), the bio-cultural relationship of humans to eating and food “is now firmly implanted as a valuable tool to explore aspects of a society’s social, political and religious make up.” In the . 5(11): 57–89. ©5 Tzu-Lung Chiu THE Practice of FastinG AFTER MiddaY IN ContemporarY Chinese NUNNERIES realm of food and religion, food control and diet prohibitions exist in different forms in many world faiths. According to Émile Durkheim (1915:306), “[i]n general, all acts characteristic of the ordinary life are forbidden while those of the religious life are taking place. -

Beyond Buddhist Apology the Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography Beyond Buddhist Apology The Political Use of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty (r.502-549) Tom De Rauw ii To my daughter Pauline, the most wonderful distraction one could ever wish for and to my grandfather, a cakravartin who ruled his own private universe iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Although the writing of a doctoral dissertation is an individual endeavour in nature, it certainly does not come about from the efforts of one individual alone. The present dissertation owes much of its existence to the help of the many people who have guided my research over the years. My heartfelt thanks, first of all, go to Dr. Ann Heirman, who supervised this thesis. Her patient guidance has been of invaluable help. Thanks also to Dr. Bart Dessein and Dr. Christophe Vielle for their help in steering this thesis in the right direction. I also thank Dr. Chen Jinhua, Dr. Andreas Janousch and Dr. Thomas Jansen for providing me with some of their research and for sharing their insights with me. My fellow students Dr. Mathieu Torck, Leslie De Vries, Mieke Matthyssen, Silke Geffcken, Evelien Vandenhaute, Esther Guggenmos, Gudrun Pinte and all my good friends who have lent me their listening ears, and have given steady support and encouragement. To my wife, who has had to endure an often absent-minded husband during these first years of marriage, I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude. She was my mentor in all but the academic aspects of this thesis. -

Institutional Entrepreneurship and Permaculture: a Practice Theory Perspective

Institutional entrepreneurship and permaculture: a practice theory perspective Article (Accepted Version) Genus, Audley, Iskandarova, Marfuga and Brown, Chris Warburton (2021) Institutional entrepreneurship and permaculture: a practice theory perspective. Business Strategy and the Environment. pp. 1-14. ISSN 0964-4733 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/95322/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Institutional -

Oythe of Cheap

LIVING FULLY • Spirit the Mariellen Ward oydiscovers that living of simply doesn’t just make good financial cheap sense. It’s a joyous way to be. Illustration: Kagan McLeod My friend Shelly Rowen and I were stretched out on the grass on our blue yoga mats. The summer sun was beating down on the unadorned and unshaded backyard of my rented flat. We were talking about the economy and our shrinking incomes when she said, “I’m using up all of my old lipsticks, the ones that are just nubs. And I’m using up all of my bottles of hand cream and moisturizer too, before I buy more.” “I’m watching for specials at the grocery store,” I said. “And I choose local items, such as apples, rather than fancy imported items, such as Japanese pears.” And then I noticed something: Shelly was smiling. And so was I. This was the moment when I was surprised to discover that I was actually enjoying frugality. I didn’t feel down about it, and neither did Shelly. In fact, we both felt good about our fiscally and environmentally responsible ways. I realized that we had both embraced the idea that living simply can be deeply satisfying. You can be frugal and joyful. And that’s what’s different about the new frugality. In the past, thrift always felt thin-lipped and dour to me. My parents lived through the Great Depression, which, at least in books and movies about those days, seems like it was hard and grim. But a paradigm shift is underway that includes a new awareness of the impact human behaviour is having on the environment and a growing realization that all of the stuff we surround ourselves with does not make us any happier. -

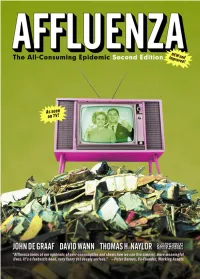

Affluenza: the All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition

An Excerpt From Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition by John de Graaf, David Wann, & Thomas H. Naylor Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers contents Foreword to the First Edition ix part two: causes 125 Foreword to the Second Edition xi 15. Original Sin 127 Preface xv 16. An Ounce of Prevention 133 Acknowledgments xxi 17. The Road Not Taken 139 18. An Emerging Epidemic 146 Introduction 1 19. The Age of Affluenza 153 20. Is There a (Real) Doctor in the House? 160 part one: symptoms 9 1. Shopping Fever 11 part three: treatment 2. A Rash of Bankruptcies 18 171 21. The Road to Recovery 173 3. Swollen Expectations 23 22. Bed Rest 177 4. Chronic Congestion 31 23. Aspirin and Chicken Soup 182 5. The Stress Of Excess 38 24. Fresh Air 188 6. Family Convulsions 47 25. The Right Medicine 197 7. Dilated Pupils 54 26. Back to Work 206 8. Community Chills 63 27. Vaccinations and Vitamins 214 9. An Ache for Meaning 72 28. Political Prescriptions 221 10. Social Scars 81 29. Annual Check-Ups 234 11. Resource Exhaustion 89 30. Healthy Again 242 12. Industrial Diarrhea 100 13. The Addictive Virus 109 Notes 248 14. Dissatisfaction Guaranteed 114 Bibliography and Sources 263 Index 276 About the Contributors 284 About Redefining Progress 286 vii preface As I write these words, a news story sits on my desk. It’s about a Czech supermodel named Petra Nemcova, who once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue. Not long ago, she lived the high life that beauty bought her—jet-setting everywhere, wearing the finest clothes. -

Teacher's Guide

A 56 minute video In 2 parts for classrooms- 29/27 minutes Produced by John de Graaf and Vivia Boe A co-production of KCTS Seattle & Oregon Public Broadcasting Teacher’s Guide by Francine Strickwerda and Ti Locke AFFLUENZA will expose students to the problem of overconsumption and its effects on the society and the environment. The one-hour program takes a hard, sometimes humorous look at the American passion for shopping, and how it leads to debt and stress for families, communities, the nation and the world. It also explores the strategies used by marketers to sell products to young people. The program is appropriate for students grade 6-12, and in universities, and will be a useful resource for teachers of communications, economics, mathemat- ics, social studies, environmental studies and the arts. Each activity in this guide references a clip from the video, and discussion questions, which can be used before and after viewing the clip. Counters differ on VHS machines, so the starting and ending points for clips are approximate. Many activities also have background information and reproducible worksheets. CONTENTS Language Arts / Social Studies 3What is Affluenza? 5Worksheet- Family Interview Communications / Business / Economics 6 Activity #1 What are Advertisers really selling? 8 Activity #2 Who are advertisers selling to? 9 Activity #3 Advertising inSchools 10 Activity #4 Be an Adbuster Mathematics / Economics / Life Skills 12 #1 Credit Quandaries 15 Worksheet- Credit Cards: The Fine Print Social Studies / Environmental Studies 16 Activity #1 Popcorn Party 18 Activity #2 A Small World 20 Activity #3 A History of Wanting More 21 Worksheet - The Impact of Stuff Language Arts / Art 22 The Good Life References 23 Books 27 Organizations 31 Internet Quiz 32 What is Affluenza? 36 Do you have it? Bullfrog Films PO Box 149, Oley PA 19547 Phone: (610) 779-8226 or (800) 543-3764 Fax: (610) 370-1978 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bullfrogfilms.com © Copyright 1997. -

06 Ngo Dinh Bao.Indd

The Concept and Practices of Mahayana Buddhist Vegetarianism in Vietnamese Society Ven. Ngo Dinh Bao Hiep, Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull International Buddhist Studies College (IBSC) Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Thailand Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract The objectives of this paper are 1) to study the concept of vegetarianism in Mahayana Buddhist canon; 2) to study the concept and practice of Mahayana Buddhist Vegetarianism in Vietnamese society and 3) to analyze the roles of Mahayana Buddhist vegetarian in Vietnamese society. This qualitative study rotate issue on the concept and practice of Mahayana Buddhist Vegetarianism in Vietnam society. The study is also found that it is not necessary for one to be a vegetarian in order to become a Buddhist. Buddhist motivations for abstaining from meat-eating draw from a wide range of traditions. Theravada tradition emphasizes non-harming, Right Livelihood, and detachment; Mahayana tradition highlights interdependence, Buddha-nature, and compassion. Keywords: Mahayana Buddhism, vegetarianism, Vietnamese society. 78 JIABU | Vol. 12 No.1 (January – June 2019) 1. Introduction It must be said that, in all Mahayana sutras, there is no sutra allowed to eat meat. Not only that, the Buddha also explicitly stated that human should be preventing from meat eating. From Mahayana scriptures, the Buddha clearly states that all sentient beings are equal because they all have Buddha-nature and will be enlightened in the future: “I am the Buddha, and sentient beings will be the Buddha.” “Sabbe tasanti dandassa sabbe bhayanti maccuno attanam upamam katva na haneyya na ghataye”. (All are afraid of the stick, all fear death. -

A Brief History of Frugality Discourses in the United States Terrence H

GCMC_A_479219.fm Page 235 Friday, July 16, 2010 8:41 PM Consumption Markets & Culture Vol. 13, No. 3, September 2010, 235–258 A brief history of frugality discourses in the United States Terrence H. Witkowski* 5 Department of Marketing, California State University, Long Beach, California, USA TaylorGCMC_A_479219.sgm10.1080/10253861003786975Consumption,1025-3866Original2010Taylor133000000SeptemberTerrenceWitkowskiwitko@csulb.edu and& Article Francis (print)/1477-223XFrancis Markets 2010 and Culture (online) Public discourses advocating frugal consumption have had a long history in the United States. This study provides a brief account of six different periods of such anti-consumerist thought and rhetoric: colonial, antebellum, Gilded Age, early 10 twentieth century, World War II, and late twentieth century. The final section uses history to better understand the religious, political, and societal tensions that have characterized American frugality discourses. Keywords: anti-consumption; frugality; thrift; US history 15 In the Fall of 2002, a small group of concerned Christians calling itself “The Evangel- ical Environmental Network” launched a media campaign built around the headline “What Would Jesus Drive?” An advertisement published on their website and in Christianity Today juxtaposed an image of Jesus at prayer with a photo of freeway 20 congestion (Figure 1). The copy attacked car pollution for the illness and death it causes – the elderly, poor, sick, and young being the most afflicted – and for its contribution to global warming. The appeal concluded as follows: Transportation is now a moral choice and an issue for Christian reflection. It’s about more than engineering – it’s about ethics. About obedience. About loving our neighbor. 25 So what would Jesus drive? We call upon America’s automobile industry to manufacture more fuel-efficient vehicles. -

The Wisdom of Frugality

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction For well over two thousand years frugality and simple liv- ing have been recommended and praised by people with a reputation for wisdom. Philosophers, prophets, saints, poets, culture critics, and just about anyone else with a claim to the title of “sage” seem generally to agree about this. Frugality and simplicity are praiseworthy; extrava- gance and luxury are suspect. This view is still widely promoted today. Each year new books appear urging us to live more economically, advising us how to spend less and save more, critiquing consumerism, or extolling the pleasures and benefits of the simple life.1 Websites and blogs devoted to frugality, simple living, downsizing, downshifting, or living slow are legion.2 The magazine Simple Living can be found at thou- sands of supermarket checkout counters. All these books, magazines, e- zines, websites, and blogs are full of good ideas and sound precepts. Some mainly offer advice regarding personal finance along with ingenious and useful money- saving tips. (The advice is usually excellent; the tips vary in value. I learned from For general queries, contact [email protected] 260966ZZI_WISDOM_CS6_PC.indd 1 30/06/2016 08:57:42 © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without -

Buddhism Between Abstinence and Indulgence: Vegetarianism in the Life and Works of Jigme Lingpa

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein Religion & Philosophy Faculty Scholarship Religion & Philosophy 2013 Buddhism Between Abstinence and Indulgence: Vegetarianism in the Life and Works of Jigme Lingpa Geoffrey Barstow Otterbein University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/religion_fac Part of the Religion Commons Repository Citation Barstow, Geoffrey, "Buddhism Between Abstinence and Indulgence: Vegetarianism in the Life and Works of Jigme Lingpa" (2013). Religion & Philosophy Faculty Scholarship. 6. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/religion_fac/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion & Philosophy at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion & Philosophy Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/ Volume 20, 2013 Buddhism Between Abstinence and Indulgence: Vegetarianism in the Life and Works of Jigmé Lingpa Geoffrey Barstow Otterbein University Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Repro- duction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the author. All enquiries to: [email protected]. Buddhism Between Abstinence and Indulgence: Vegetarianism in the Life and Works of Jigmé Lingpa Geoffrey Barstow1 Abstract Tibetan Buddhism idealizes the practice of compassion, the drive to relieve the suffering of others, including animals. At the same time, however, meat is a standard part of the Tibetan diet, and abandoning it is widely understood to be difficult.