Preventing Fishing Gear Loss from Vessel Interactions in New England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A-Water Quality-Town Of

Appendix A Water Quality – Town of Greenwich Town of Greenwich Drainage Manual February 2012 [This page left intentionally blank] Impaired Water Bodies – Town of Greenwich Water Body Impaired Segment Location Cause Potential Source Segment Designated Use Size From mouth at Greenwich Harbor (just downstream [DS] of I95 crossing, at exit Habitat for Fish, Horseneck 5.78 3 offramp), US to Putnam Lake Other Aquatic Cause Unknown Source Unknown Brook-01 Miles Reservoir outlet dam (just upstream [US] Life and Wildlife of Dewart Road crossing) From head of tide (US of Route 1 Habitat for Fish, Sources Outside State Jurisdiction or Borders, Source crossing, at INLET to ponded portion of Other Aquatic Cause Unknown Unknown, Highway/Road/Bridge Runoff (Non- Byram River- river, just DS of Upland Street East 0.49 Life and Wildlife construction Related) 01 area), US to Pemberwick outlet dam (US Miles Illicit Connections/Hook-ups to Storm Sewers, Source of Comly Avenue crossing, and US of Recreation Escherichia coli Unknown confluence with Pemberwick Brook Putnam Lake Habitat for Fish, Impoundment of Horseneck Brook, just 95.56 Alterations in wetland Reservoir Other Aquatic Habitat Modification - other than Hydromodification south of Rt. 15 Acres habitats (Greenwich) Life and Wildlife Western portion of LIS, Inner Estuary, Dissolved oxygen LIS WB Inner - upper Indian Harbor (lower portion of Habitat for 0.025 saturation; Nutrient/ Residential Districts, Municipal Point Source Indian Harbor Greenwich Creek) from Davis Avenue Marine Fish, Square Eutrophication Discharges, Non-Point Source, Unspecified Urban (upper), crossing, US to saltwater limit at West Other Aquatic Miles Biological Indicators; Stormwater Greenwich Brother Drive crossing (includes I95 Life and Wildlife Oxygen, Dissolved crossing). -

News Release

The Long Island Sound Office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Look For Us On The World Wide Web http://www.longislandsoundstudy.net A Partnership to Restore and Protect the Sound NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jane MacLellan, Fish and Wildlife Service Liaison with the EPA LIS Office, (203) 977-1541 LISS Identifies Significant Coastal Areas for Stewardship Stamford, CT, June 10, 2005 -- The Long Island Sound Study Stewardship Initiative is working to identify places along the Sound’s coast with significant ecological, scientific, or recreational values. Now, the LISS will present to the public a list of areas around Long Island Sound that best exemplify those values (attachment). A series of public meetings sponsored by the Study’s Long Island Sound Stewardship Initiative are scheduled between June 13 and June 22 in several Connecticut and New York locations. Public input is being sought on the draft list of inaugural stewardship areas. Each area includes sites of natural habitat important for wildlife or sites that support recreation activities and access to Long Island Sound. Each meeting will feature a local expert who will talk about the values of a specific local site and specific opportunities for improved stewardship. Information on the Long Island Sound Stewardship Act legislation that has been introduced in Congress will also be provided. Based on recommendations of the Long Island Sound Study Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan and the 2003 Long Island Sound Agreement, the Stewardship Initiative is a collaborative effort to identify places with significant ecological or recreational value throughout the Sound and develop a strategy to protect and enhance these special places. -

A Q U I F E R P R O T E C T I O N a R E a S N O R W a L K , C O N N E C T I C

!n !n S c Skunk Pond Beaver Brook Davidge Brook e d d k h P O H R R O F p S o i d t n n l c t u i l R a T S d o i ll l t e e lv i d o t R r r d r l h t l l a H r n l t r M b a s b R d H e G L R o r re R B C o o u l e t p o n D o e f L i s Weston Intermediate School y l o s L d r t e Huckleberry Hills Brook e t d W d r e g Upper Stony Brook Pond N L D g i b R o s n Ridgefield Pond a t v d id e g e H r i l Country Club Pond b e a R d r r S n n d a g e L o n tin a d ! R d l H B n t x H e W Still Pond d t n Comstock Knoll u d a R S o C R k R e L H d i p d S n a l l F tt h Town Pond d l T te r D o e t l e s a t u e L e c P n n b a n l R g n i L t m fo D b k H r it to Lower Stony Brook Pond o r A d t P n d s H t F u d g L d d i Harrisons Brook R h e k t R r a e R m D l S S e e G E o n y r f ll H rt R r b i i o e n s l t ld d d o r l ib l a e r R d L r O e H w i Fanton Hill g r l Cider Mill School P y R n a ll F i e s w L R y 136 e a B i M e C H k A s t n d o i S d V l n 3 c k r l t g n n a d R i u g d o r a L 3 ! a l r u p d R d e c L S o s e Hurlbutt Elementary School R d n n d D A i K w T n d o O n D t f R l g d R l t ad L i r e R e e r n d L a S i m a o f g n n n D d n R o t h n Middlebrook School ! l n t w Lo t a 33 i n l n i r E id d D w l i o o W l r N e S a d l e P g n V n a h L C r L o N a r N a S e n e t l e b n l e C s h f ! d L nd g o a F i i M e l k rie r id F C a F r w n P t e r C ld l O e r a l y v f e u e o O n e o a P i O i s R w e t n a e l a n T t b s l d l N l k n t g i d u o e a o R W R Hasen Pond n r r n M W B y t Strong -

2018 CT IWQR Appendix

1 Appendix A-3. Connecticut 305b Assessment Results for Estuaries Connecticut 2018 305b Assessment Results Estuaries Appendix A-3 Waterbody Waterbody Square Segment ID Name Location Miles Aquatic Life Recreation Shellfish Shellfish Class See Map for Boundaries. Central portion of LIS, LIS CB Inner - Inner Estuary, Patchogue and Menunketesuck Rivers Patchogue And from mouths at Grove Beach Point, US to saltwater Menunketesuc limits just above I95 crossing, and at I95 crossing NOT Direct CT-C1_001 k Rivers respectively, Westbrook. 0.182 UNASSESSED UNASSESSED SUPPORTING Consumption See Map for Boundaries. Central portion of LIS, LIS CB Inner - Inner Estuary, SB water of inner Clinton Harbor, Inner Clinton including mouths of Hammonasset, Indian, Harbor, Hammock Rivers, and Dudley Creek (includes NOT FULLY Commercial CT-C1_002-SB Clinton Esposito Beach), Clinton. 0.372 SUPPORTING UNASSESSED SUPPORTING Harvesting See Map for Boundaries. Central portion of LIS, Inner Estuary, Hammonasset River SB water from LIS CB Inner - mouth at inner Clinton Harbor, US to SA/SB water Hammonasset quality line between Currycross Road and RR track, NOT Commercial CT-C1_003-SB River, Clinton Clinton. 0.072 UNASSESSED UNASSESSED SUPPORTING Harvesting 2 See Map for Boundaries. Central portion of LIS, Inner Estuary, Hayden Creek SB water from mouth LIS CB Inner - at Hammonasset River (parallel with Pratt Road), US Hayden Creek, to saltwater limit near Maple Avenue (off Route 1), NOT Commercial CT-C1_004-SB Clinton Clinton. 0.009 UNASSESSED UNASSESSED SUPPORTING Harvesting See Map for Boundaries. Central portion of LIS, Inner Estuary, (DISCONTINUOUS SEGMENT) SA LIS CB Inner - water of upper Hammonasset, Indian, Hammock Clinton Harbor Rivers, Dudley Creek and other small tributaries, (SA Inputs), from SA/SB water quality line, US to saltwater NOT Direct CT-C1_005 Clinton limits, Clinton. -

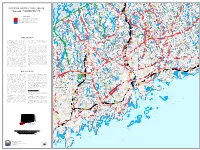

Waterbody Regulations and Boat Launches

to boating in Connecticut! TheWelcome map with local ordinances, state boat launches, pumpout facilities, and Boating Infrastructure Grant funded transient facilities is back again. New this year is an alphabetical list of state boat launches located on Connecticut lakes, ponds, and rivers listed by the waterbody name. If you’re exploring a familiar waterbody or starting a new adventure, be sure to have the proper safety equipment by checking the list on page 32 or requesting a Vessel Safety Check by boating staff (see page 14 for additional information). Reference Reference Reference Name Town Number Name Town Number Name Town Number Amos Lake Preston P12 Dog Pond Goshen G2 Lake Zoar Southbury S9 Anderson Pond North Stonington N23 Dooley Pond Middletown M11 Lantern Hill Ledyard L2 Avery Pond Preston P13 Eagleville Lake Coventry C23 Leonard Pond Kent K3 Babcock Pond Colchester C13 East River Guilford G26 Lieutenant River Old Lyme O3 Baldwin Bridge Old Saybrook O6 Four Mile River Old Lyme O1 Lighthouse Point New Haven N7 Ball Pond New Fairfield N4 Gardner Lake Salem S1 Little Pond Thompson T1 Bantam Lake Morris M19 Glasgo Pond Griswold G11 Long Pond North Stonington N27 Barn Island Stonington S17 Gorton Pond East Lyme E9 Mamanasco Lake Ridgefield R2 Bashan Lake East Haddam E1 Grand Street East Lyme E13 Mansfield Hollow Lake Mansfield M3 Batterson Park Pond New Britain N2 Great Island Old Lyme O2 Mashapaug Lake Union U3 Bayberry Lane Groton G14 Green Falls Reservoir Voluntown V5 Messerschmidt Pond Westbrook W10 Beach Pond Voluntown V3 Guilford -

2021 Connecticut Boater's Guide Rules and Resources

2021 Connecticut Boater's Guide Rules and Resources In The Spotlight Updated Launch & Pumpout Directories CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION HTTPS://PORTAL.CT.GOV/DEEP/BOATING/BOATING-AND-PADDLING YOUR FULL SERVICE YACHTING DESTINATION No Bridges, Direct Access New State of the Art Concrete Floating Fuel Dock Offering Diesel/Gas to Long Island Sound Docks for Vessels up to 250’ www.bridgeportharbormarina.com | 203-330-8787 BRIDGEPORT BOATWORKS 200 Ton Full Service Boatyard: Travel Lift Repair, Refit, Refurbish www.bridgeportboatworks.com | 860-536-9651 BOCA OYSTER BAR Stunning Water Views Professional Lunch & New England Fare 2 Courses - $14 www.bocaoysterbar.com | 203-612-4848 NOW OPEN 10 E Main Street - 1st Floor • Bridgeport CT 06608 [email protected] • 203-330-8787 • VHF CH 09 2 2021 Connecticut BOATERS GUIDE We Take Nervous Out of Breakdowns $159* for Unlimited Towing...JOIN TODAY! With an Unlimited Towing Membership, breakdowns, running out GET THE APP IT’S THE of fuel and soft ungroundings don’t have to be so stressful. For a FASTEST WAY TO GET A TOW year of worry-free boating, make TowBoatU.S. your backup plan. BoatUS.com/Towing or800-395-2628 *One year Saltwater Membership pricing. Details of services provided can be found online at BoatUS.com/Agree. TowBoatU.S. is not a rescue service. In an emergency situation, you must contact the Coast Guard or a government agency immediately. 2021 Connecticut BOATER’S GUIDE 2021 Connecticut A digest of boating laws and regulations Boater's Guide Department of Energy & Environmental Protection Rules and Resources State of Connecticut Boating Division Ned Lamont, Governor Peter B. -

LISS 3.3.Qxd

RestoringRestoring LongLong CONNECTICUT Connecticut Quinnipiac River River IslandIsland Thames Sound’s River Sound’s Housatonic River Stonington HabitatsHabitats Old Saybrook COMPLETED RESTORATION SITES IN PROGRESS RESTORATION SITES POTENTIAL RESTORATION SITES PROJECT BOUNDARY RIVER LONG ISLAND SOUND Greenwich 2002 RESTORATION SITES Southold BLUE INDICATES COMPLETED SITE – CONSTRUCTION ON THE PROJECT IS FINISHED, BUT MONITORING MAY BE ON-GOING GREEN INDICATES IN PROGRESS SITE– SOME PHASE OF THE PROJECT IS UNDERWAY, E.G. APPLYING FOR FUNDING, DESIGN, OR CONSTRUCTION BLACK INDICATES POTENTIAL SITE – A RESTORATION PROJECT HAS BEEN IDENTIFIED, NO ACTION TAKEN YET MOUNT VERNON RYE BOLDFACE IN ALL COLORS INDICATES HIGH-RANKED SITES Rye Glover Field (FW) Beaver Swamp Brook (FW) Beaver Swamp Brook/Cowperwood site (FW) Brookhaven NEW ROCHELLE Blind Brook (FW) Echo Bay (TW/SR/IF/RI) Edith G. Read Wildlife Sanctuary (TW/F/EE/FW) CONNECTICUT Former Dickerman’s Pond (FW) Marshlands Conservancy (TW/F/IF) Farm River (TW) EW ORK Nature Study Woods (F/FW) Farm River tributary/Edgemere Rd. (TW) N Y Pryer Manor Marsh (TW) SMITHTOWN BRANFORD Morris Creek/Sibley Lane (TW) Callahan’s Beach (CB) Branford River STP (TW) New Haven Airport (TW) Bronx BRONX NORTH HEMPSTEAD Fresh Pond (FW/F/BD) Branford R./Christopher Rd. (TW) Nissequogue Bronx Oyster Reefs (SR) Baxter Estates Pond (FW) Harrison Pond Town Park (FW/RMC/TW/F) Branford R./St. Agnes Cemetery (TW) EAST LYME NEW YORK Bronx River mouth (TW/F/RMC) Hempstead Harbor (EE/IF/TW) Landing Avenue Town Park (TW) Branford R./Hickory Rd. (TW) Brides Brook Culvert (RMC/TW) River Bronx River Trailway (TW/FW/F/RMC) Lake Success (FW) Long Beach (BD) Branford R. -

CT DEEP 2018 FISHING REPORT NUMBER 23 9/27/2018 False Albacore (Euthynnus Alletteratus) Channel Catfish (Ictalurus Punctatus) YOU CAN FIND US DIRECTLY on FACEBOOK

CT DEEP 2018 FISHING REPORT NUMBER 23 9/27/2018 False Albacore (Euthynnus alletteratus) Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) YOU CAN FIND US DIRECTLY ON FACEBOOK. This page features a variety of information on fishing, hunting, and wildlife watching in Connecticut. The address is www.facebook.com/CTFishandWildlife. INLAND REPORT Providers of some of the information below included Candlewood Lake Bait & Tackle, Bob’s Place, JT’s Fly Shop, Yankee Outdoors, CTFisherman.com, and a number of bass fishing clubs & organizations. LARGEMOUTH BASS fishing has been spotty with some fish in transition from summer to fall habits. Places to try include Candlewood Lake (anglers are finding some big largemouths in the grass), Bantam Lake, Highland Lake, Park Pond, Winchester Lake, Congamond Lakes, East and West Twin Lakes, Quinebaug Lake, Quaddick Lake and Crystal Lake. Tournament angler reports are from Hopeville Pond (good for a few, tough for many, a 4 lb lunker but not much else of any size), Long Pond (slow to fair for most, great for a few, with a 6.38 lb lunker), Quaddick Lake (fair at best, only a 2.63 lb lunker), Lake Lillinonah (fair, with a 6.56 lb lunker), and the Connecticut River (fair for an evening club out of Salmon River, 2.14 lb lunker). SMALLMOUTH BASS. Fair reports from Candlewood Lake (lots of suspended smallies, not much on structure) and Lake Lillinonah. Tournament angler are from Candlewood Lake (slow for many) and Lake Lillinonah (fair). TROUT and Salmon Stocking Update- Fall stocking in Rivers and Streams is on hold- too much water! Look for more widespread stocking in lakes and ponds and trout parks coming next week. -

2015 Connecticut

2015 CONNECTICUT BOAter’sREGULATION RESOURCE &GUIDE STATE OF CONNECTICUT Department of Energy & Environmental Protection 79 Elm Street, Hartford, CT 06106-5127 www.ct.gov/deep The Boater’s Guide is available at any Department of Motor Vehicle Office, local Town Halls, and many marinas and yacht clubs. YOUR SOURCE for Superior Boating Education America’s Boating Course ® Our course qualifies you for the Connecticut Safe Boating Certificate. Courses and Seminars Sailing, Navigation, Piloting, Weather, Seamanship, Engine Maintenance, Marine Electronics, VHF/DSC Radio, GPS, Powerboat Handling, Anchoring, Trailering, PWC (Jet Ski), and much more. Find a Squadron and Courses Near You 888-367-8777 www.usps.org United States Power Squadrons® in Connecticut Power, Sail, and Paddle Sports Celebrating 100 Years of Excellence in Boating Education © 2014 United States Power Squadrons 2015 Connecticut BOATERS GUIDE Connecticut Department of ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTALConnecticut Department of PROTECTIONENERGY & RobertENVIRONMENTAL J. Klee, Commissioner PROTECTION Dear ConnecticutRobert Boaters, J. Klee, Commissioner Thank you for taking advantage of the wonderful recreational boating opportunities found on Connecticut’sDear Connecticut waters. Boaters, Our lakes, streams, rivers, and Long Island Sound coastline provided an unrivaled variety of exciting boating experiences. Thank you for taking advantage of the wonderful recreational boating opportunities found on To helpConnecticut’s you have waters.an enjoyable, Our lakes, safe, streams,and environmentally rivers, and Long sound Island time Sound on the coastline water, providedwe are pleased an unrivaled to providevariety the of 2015 exciting Boater’s boating Guide. experiences. This annual publication makes readily available to you a comprehensive summary of Connecticut boating laws and regulations – as well as a variety of other informationTo help you that have we thinkan enjoyable, you will findsafe, useful. -

Connecticut Wildlife Jan/Feb 2015

January/February 2015 CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION BUREAU OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISIONS OF WILDLIFE, INLAND & MARINE FISHERIES, AND FORESTRY January/February 2015 Connecticut Wildlife 1 Volume 35, Number 1 ● January/February 2015 Eye on Connecticut Wildlife the Wild Published bimonthly by Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Going Back in Time Bureau of Natural Resources Wildlife Division As the Coordinator for the DEEP Wildlife Division’s Landowner Incentive Program www.ct.gov/deep (LIP), it has been deeply gratifying to not only be able to help implement large-scale Commissioner habitat enhancement projects on private land, but to also work with landowners, such Robert Klee as Paul Chase of Montville, Connecticut, who are deeply committed to their land and Deputy Commissioner the wildlife that calls it home. Paul wrote the article entitled “Going Back in Time” on Susan Whalen page 10 of this issue. It is his personal account of undertaking a LIP project to restore, Chief, Bureau of Natural Resources create, and manage 16.5 acres of young forest on his 110-acre property. LIP was William Hyatt Director, Wildlife Division initially made possible by a competitive grant awarded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Rick Jacobson Service to the Wildlife Division, enabling the Division to set up its own competitive grant program to restore, create, and enhance wildlife habitat for species at risk on Magazine Staff private land. Paul’s project is the 40th LIP-funded project to be completed and only Managing Editor Kathy Herz a handful of projects remain to be done. -

WHOI-R-83-017 Aubrey, David G. Beach

In A. McLachlan and T. Erasmus, (eds~), Sandy Beaches as Eco 63 sy~tems, D.W. Junk Publishers, ' The Hague, p. 63-85, 1983. BEACH CHANGES ON COASTS lHTH DIFFERENT WAVE CLHIATES D. G. AUBREY (Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) severe wave climate) and the lowest / vari abi 1i ty along protected coasts (1 east severe wave climate). All open coast ,r-· locations studied had a seasonal variability SYNOPSIS "'".,. __..-, Seasonal and longer-term oeach which accounted for at least50%of th~ beach variability is quantified for seven U.S. variability. Protected coastal locations beaches exposed to widely varying wave had less pronounced seasonal signatures. climates. One U.S. west coast location These seasonal and aseasonal beach responses (southern California) and six U.S. east mirror corresponding seasonality (or lack coast locations (from North Carolina to thereof) in wave and storm climates. The Massachusetts) form the basis of this study re-emphasizes the need for careful study. Wave exposure varies from complete measurement or estimation of coastal wave exposure to open ocean waves, to partly climate to enable predictive modelling of sheltered locations, and finally to nearly shorelin-e behaviour, and discusses different complete sheltering where locally-generated analysis techniques for analyzing changes in waves dominate. Beach response was beach profiles through time. documented with beach profiles distributeq INTRODUCTION along each of the seven coastal locations, Quantification of spatial and temporal spanning a minimum of 'five years of observa scales of beach change is vital to a wide tion. Frequency of measurement was at least variety of scientific and engineering once per month, with periods of more intense investigations of nearshore environments. -

CONNECTICUT Estbrook Harbor

280 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 8 Chapter 2, Pilot Coast U.S. 72°30'W 72°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 8 Hartford NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 12378 73°W CONNECTICUT Norwich 12372 41°30'N C O 12377 THAMES RIVER N N E C T I C U T R I V E R 12375 New London 12372 12354 Essex HOUSATONIC RIVER New Haven NIANTIC BAY 13213 12371 12373 12374 Westbrook Harbor 13211 Branford Harbor Guilford Harbor 12372 BLOCK ISLAND SOUND 12358 Orient Point 12370 LONG ISLAND SOUND 41°N 12362 Port Je erson L ONG ISLAND NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN 19 SEP2021 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 8 ¢ 281 Eastern Long Island Sound (1) This chapter describes the eastern portion of Long by small vessels when meeting unfavorable weather or Island Sound following the north shore from Thames reaching the eastern part of the sound. Small vessels can River to and including the Housatonic River and then select anchorage eastward or westward of Kelsey Point the south shore from Orient Point to and including Port Breakwater, also in Duck Island Roads. Off Madison Jefferson. Also described are the Connecticut River; the there is anchorage sheltered from northerly winds. New ports of New London, New Haven and Northville; and the Haven Harbor is an important harbor of refuge. more important fishing and yachting centers on Niantic (11) Several general anchorages are in Long Island River and Bay, Westbrook Harbor, Guilford Harbor, Sound.