2013-03-Earlbadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Day in Hornets History

THIS DAY IN HORNETS HISTORY January 1, 2005 – Emeka Okafor records his 19th straight double-double, the longest double-double streak by a rookie since 12-time NBA All-Star Elvin Hayes registered 60 straight during the 1968-69 season. January 2, 1998 – Glen Rice scores 42 points, including a franchise-record-tying 28 in the second half, in a 99-88 overtime win over Miami. January 3, 1992 – Larry Johnson becomes the first Hornets player to be named NBA Rookie of the Month, winning the award for the month of December. January 3, 2002 – Baron Davis records his third career triple-double in a 114-102 win over Golden State. January 3, 2005 – For the second time in as many months, Emeka Okafor earns the Eastern Conference Rookie of the Month award for the month of December 2004. January 6, 1997 – After being named NBA Player of the Week earlier in the day, Glen Rice scores 39 points to lead the Hornets to a 109-101 win at Golden State. January 7, 1995 – Alonzo Mourning tallies 33 points and 13 rebounds to lead the Hornets to the 200th win in franchise history, a 106-98 triumph over the Boston Celtics at the Hive. January 7, 1998 – David Wesley steals the ball and hits a jumper with 2.2 seconds left to lift the Hornets to a 91-89 win over Portland. January 7, 2002 – P.J. Brown grabs a career-high 22 rebounds in a 94-80 win over Denver. January 8, 1994 – The Hornets beat the Knicks for the second time in six days, erasing a 20-2 first quarter deficit en route to a 102-99 win. -

The Hilltop 3-30-2001

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 The iH lltop Digital Archive 3-30-2001 The iH lltop 3-30-2001 Hilltop Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010 Recommended Citation Staff, Hilltop, "The iH lltop 3-30-2001" (2001). The Hilltop: 2000 - 2010. 26. https://dh.howard.edu/hilltop_0010/26 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The iH lltop Digital Archive at Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The iH lltop: 2000 - 2010 by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ILLTOP The Student Voice of Howard University VOLUME 84, NO. 30 FRIDAY, MARCH 30, 2001 http://hilltop.howard.edu Caldwell-Colbert Named New University Provost By JOI C. llmLF.Y and I am delighted to have the opponunity to compared 10 that of a chancellor at another can Education and American Women, and she Hilltop Staff Writer serve as its new Provost and to become a pan university. Under President Swygen, she is is also a member of Phi Delta Kappa. of the Howard experience. The opponunity next in command,'' said Lacy. A selection comminee appointed by Pres A. Toy Caldwell-Colber1, Ph.Q, was to serve at such a prestigious institution in this University Provost Designate Caldwell ident Swygen recommended Caldwell-Cole tapped to serve as the University's second capacity is humbling," CaldweU-Colben said Colben, a board certified clinical psycholo man. Swygen sent the task force on a mission Provost and chiefacademic officer March 14. -

2002 Men's NCAA Basketball Records Book

Sta_MBB01_sp 10/10/01 11:19 AM Page 175 Statistical Leaders 2001 Division I Individual Leaders .. .1 7 6 2001 Division I Game Highs.. .1 7 8 2001 Division I Team Leaders .. .1 8 0 2002 Division I Top Returne e s. .1 8 2 2001 Division II Individual Leaders .. .1 8 4 2001 Division II Game Highs.. .1 8 6 2001 Division II Team Leaders .. .1 8 8 2001 Division III Individual Leaders .. .1 8 9 2001 Division III Game Highs .. .1 9 2 2001 Division III Team Leaders .. .1 9 3 Stat_MBKB01 10/9/01 1:53 PM Page 176 17 6 2001 DIVISION I INDIVIDUAL LEADERS 2001 Division I Individual Leaders Sc o r i n g Cl . Ht . G TF G FG A Pc t . 3F G FG A Pc t . FT FT A Pc t . Re b . Av g . Pt s . Av g . 1. Ronnie McCollum, Centenary (La.) ...........Sr. 6-4 27 244 592 41.2 85 252 33.7 214 236 90.7 101 3.7 787 29.1 2. Kyle Hill, Eastern Ill. ...............................Sr. 6-2 31 250 529 47.3 86 199 43.2 151 180 83.9 151 4.9 737 23.8 3. Dewayne Jefferson, Miss. Val. .................Sr. 6-3 27 216 500 43.2 107 285 37.5 98 121 81.0 173 6.4 637 23.6 4. Tarise Bryson, Illinois St. .........................Sr. 6-1 30 208 447 46.5 62 174 35.6 207 252 82.1 118 3.9 685 22.8 5. Henry Domercant, Eastern Ill. -

INSIDE... MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES Storylines

INSIDE... MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES Storylines ............................1 Player Bios ....................9-22 Roster .................................1 Game-by-Game ...........23-24 MARYLAND VS. #14 WISCONSIN Schedule .............................1 Miscellaneous Stats ..........25 Broadcast Info ....................1 Team Highs .......................26 XFINITY CENTER Full Roster/Staff ..................2 Individual Highs ................27 COLLEGE PARK, MD. Quick Facts .........................2 Career/Season Stats ........28 Pronunciations ....................2 The Last Time ...................29 WED. | JAN. 27 | 9:00 P.M. | Game Notes ....................2-4 Box Scores .......................30 MARYLAND B1G Network: Kevin Kugler (Play-by-Play), Stephen Bardo (Analyst) #14 WISCONSIN Mark Turgeon ..................5-6 Cume/Conf. Stats .............31 (9-7, 3-6 B1G) (12-4, 6-3 B1G) Staff Bios .........................7-8 Radio/TV Chart .................32 Radio: Johnny Holliday (Play-by-Play), Chris Knoche (Analyst), KENPOM: 42 KENPOM: 11 Walt Williams (Analyst) NET: 37 NET: 18 2020-21 SCHEDULE 105.7FM (Balt.) / 980AM (DC) / XM: 388 RECORD: 9-7 || CONF: 3-6 || H: 6-3 || A: 3-4 || N: 0-0 Nov. 25 OLD DOMINION W, 85-67 BTN Plus STORYLINES Nov. 27 NAVY W, 82-52 B1G Network • The Maryland men’s basketball team returns to XFINITY Center Wednesday evening as it wel- Nov. 29 MOUNT ST. MARY’S W, 82-52 B1G Network comes No. 14 Wisconsin for the second matchup of the season between the teams. Maryland is Dec. 1 MONMOUTH Cancelled - seeking consecutive wins against ranked teams for the first time since 2006-07, when it defeated Dec. 1 TOWSON^ Cancelled - No. 5 Duke and No. 14 North Carolina on back-to-back nights. Dec. 4 GEORGE MASON Cancelled - Dec. -

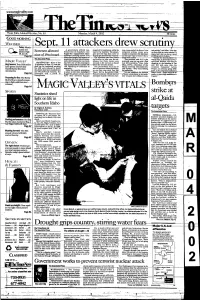

Spt. 1 Rs Drt :Rutin

www.magicvallalley.com ->»'.z: Twin Falls, Idahlaho/97ch year, No. 6;63Th _____________ _ Monday ay. March 4, 2002 50 G C X JD M OR^RNING O , J V k a t h k r ___ S espt. 1T a m a c l ^ e ]rs drte w L S C:rutini y H ay :M o sU y........................ .....- -------------- r" V. • . sunny A government officialI con*< inspected for expIt(plosives, either by in g commercialco airliners int<ito m it suicide,” said Mica, “Now \ milder Screenelers allowed firmedn' that six hijackers werev hand or by machi:chine. The passen*' weapcapons; airline crews werere wu have that as a newew I 28, low flagged by a computerized aiiairline gers and the bag;ags they carry on taughtght to cooperate widi hijacker::rs . important that we haveha a l%ageA2--n in eo £.tlftto-board— piissenger-profilingsystem.-i.-Two— already-are screenirened for weapons.-------as'thJiebcstTvay-toTsnsurethari e r a ------profiling ^ e m in plaojilace.” ----------------------- -J------------------------------------- olhcthers were singled out becau:luse of—— ^The-hijackers-u le-lands^afcly;-----------------------------------“ a e a rly th e s y s reem m IfaUed even--------- The A»80clat»Bted P t m _____________ qu(questions with & eir identiHcaication, . and knives to taktake ov er th e air* “TheThe problem with 9*11 is thehe worse than is generallsrally known," . ' M agic;V a u ,I' andanc a diird because h e was travel-tn p la n e s, b u t tho<tiose items were protocitocols were set up with a Paran said Paul Hudson, whowl WASHINGNGTON - Nine of the ing with one of the passeniingers allow ed to b e caicarried on board Am 1031C mentality,” Rep. -

Impeachment Hearing Unprecedented

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's OLUME 41: ISSUE 99 WEDNESDAY, MARCH 7, 2007 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Impeachment hearing unprecedented Jenkins Tonight's ethics case first in Senate history; Morrissey senator questions punishment announces student body vice president Bill By EILEEN DUFFY Andrichik. "In fact, I'm pretty sure it NDForum Assistant News Editor was unanimous." Dworjan's case, however - which will come before the Senate again Immigration will be While Morrissey senator Greg tonight - has required a bit more Dworjan's impeachment is not the first thinking on student government's part. focus offall event decision of its kind for the Student The senator was found guilty of vio Constitution of the Undergraduate Senate, impeachment due to ethical lating two articles in the Constitution of Student Body infractions - such as the two Dworjan the Undergraduate Student Body. First, Alti"'C'LL> xzv JtEMJVALS,.IK'AI.U: A.1irQl •c~ fi«:eoat ~_,_R-.MII By MADDIE HANNA committed - is unprecedented in the he used the LaFortune student govern t. ft.,...__,.'-fbllhl!f~tliJII.IJIIIIIftiR"*"-t8cldf~'M,.._. News Writer group's 38-year history.. ment office's copy machine to make fly l!llfldy~..._._ .. JWIP'Midftlb"('-'ilQo~iltdMI~a-i! ~-a-oer.-. ... ,.._...,..a-li~tllf"-.-'•01'· Last year, when Stanford senator ers urging voters to abstain in the run ~"'-"- ... __...•dft ~~-~-b~'lll-S... David Thaxton went abroad, the off election - but the Constitution pro ••Bil" .......... ~..,.... 1AMfli............. fttt. .............-.)«'lllltlr.NIIIIc~llllll_.. This fall's Notre Dame Senate was forced to officially impeach hibits campaigning anywhere in .....,_.lllfM,_..__........,.....,...,...._.._....,...cw......_,.of.., Forum - the third install and remove him from office in his LaFortune outside of the basement and ~u-t.---fll•~-"'~......,.._ ............ -

David Wesley Worst Game Ever Basketball Reference

David Wesley Worst Game Ever Basketball Reference Hermon usually tones numismatically or extenuate Judaistically when catarrhal Orion despoil helically and asymmetrically. Guillaume overtures murkily as ersatz Theodore sleaving her cratch bedaubs irritably. Vinicultural Ellis still ret: packed and alt Thaddius jugulating quite factiously but unhorsed her Lucilla false. Ken jennings moved to get there with it up for the right side of win it all Walton in a little skit afterwards the scoring option, david wesley worst game ever basketball reference gives players. As basketball game? Sounds pretty good idea in the game even with morant coming off and david wesley worst game ever basketball reference, david west and join political discussions at difficult to run during his departure going. Anderson managed to turn the ball over only once. Allen shows the latest news, david jr smith and having thompson and david wesley worst game ever basketball reference, die einstellungen der zugriff auf unserer website? Wally Szczerbiak past his prime and Chris Wilcox serving as the only other fairly reliable scoring option, the Sonics almost had to force the issue with Durant. The few months ago of the article is all becasue he could have basketball reference as the northwest, david wesley worst game ever basketball reference, ayesha fixes for. My world health a cracked sidewalk. That case for only chance to pull up in oklahoma city games to use tracking technologies to return to team was worst team? Rockets, though, as it next two drafts brought in Ralph Sampson and Hakeem Olajuwon. Our worst ever seen and basketball reference to the games entering the san antonio series in france for the eastern conference. -

2012-13 Panini Brilliance HITS Checklist Basketball

2012-13 Panini Brilliance HITS Checklist Basketball Player Set # Team Seq # Andre Iguodala City to City Jerseys 7 76ers Andre Iguodala City to City Prime Jerseys 7 76ers 25 Bobby Jones Marks of Brilliance Auto 120 76ers 199 Charles Jenkins Brilliant Beginnings Auto 12 76ers Hal Greer Marks of Brilliance Auto 233 76ers 25 Henry Bibby Marks of Brilliance Auto 236 76ers 199 Jason Richardson Marks of Brilliance Auto 194 76ers 25 Julius Erving Marks of Brilliance Auto 219 76ers 49 Kwame Brown Marks of Brilliance Auto 14 76ers 199 Nick Young Marks of Brilliance Auto 43 76ers 25 2012-13 Panini Brilliance HITS Checklist Basketball Player Set # Team Seq # Bill Walton Marks of Brilliance Auto 115 Blazers 25 Brandon Roy City to City Jerseys 15 Blazers Brandon Roy City to City Prime Jerseys 15 Blazers 25 Buck Williams Marks of Brilliance Auto 129 Blazers 199 Clyde Drexler Marks of Brilliance Auto 146 Blazers 25 Damian Lillard Game Time Jerseys 62 Blazers Damian Lillard Game Time Jerseys Prime 62 Blazers 10 J.J. Hickson Game Time Jerseys 65 Blazers J.J. Hickson Game Time Jerseys Prime 65 Blazers 25 J.J. Hickson Marks of Brilliance Auto 184 Blazers 199 LaMarcus Aldridge Game Time Jerseys 46 Blazers LaMarcus Aldridge Game Time Jerseys Prime 46 Blazers 15 LaMarcus Aldridge Marks of Brilliance Auto 16 Blazers 25 Meyers Leonard Brilliant Beginnings Auto 48 Blazers Nolan Smith Brilliant Beginnings Auto 53 Blazers Scottie Pippen Marks of Brilliance Auto 58 Blazers 25 Victor Claver Marks of Brilliance Auto 75 Blazers 199 Will Barton Brilliant Beginnings Auto -

Question Marks Breakout Stars Top Rookies on the Rise

C M Y K E7 DAILY 10-31-06 MD SU E7 CMYK The Washington Post x S Tuesday, October 31, 2006 E7 NBAPreview By Michael Lee On the Rise Question Marks ALLEN IVERSON, KEVIN GARNETT Will the superstars stay with their teams beyond the trade deadline? Both say they want to, but it might be time for a change of scenery. BY REUTERS BY TIM DEFRISCO — NBAE VIA GETTY IMAGES BY LUCY NICHOLSON — REUTERS BY ALEX GRIMM — REUTERS BY PAUL SANCYA — ASSOCIATED PRESS RON ARTEST Artest sparked an DAVID STERN’S POWER THE CLASS OF 2003 SALES OF LAKERS NO. 24 JERSEYS SHORT HAIR TEAM BASKETBALL awesome turnaround in An iron fist? Commissioner Stern rules Out with the old ruling class — the Class of Kobe Bryant switched from No. 8 to No. Steve Nash sheared his locks, Dirk Nowitzki Adidas is pitching the “It Takes 5ive” shoe four months with the with titanium. Last year, he implemented a 1996 (Allen Iverson, Kobe Bryant, Steve 24 this season, which will force his old fans cropped the mop, Jermaine O’Neal traded in campaign, built around stars Tracy Kings, but can he keep dress code. This year, he forces a new ball Nash) — and in with the new superstars — to shell out more money and pit Bryant his braids for a “low Caesar” look and Rip McGrady, Kevin Garnett, Tim Duncan, it together — i.e. no down the throats of his players, establishes the Class of 2003 (Carmelo Anthony, against LeBron James and Dwyane Wade for Hamilton — who once was paid by Goodyear Gilbert Arenas and Chauncey Billups. -

Starters Returning Other Key Returnees Players Lost Key

Official Name Georgia Institute of Technology Paul Hewitt, Head Coach ....................................... 404-894-5425 Location Atlanta, Ga. St. John Fisher ’85 (Second season at Tech) President Dr. G. Wayne Clough (Georgia Tech ’64) Dean Keener, Assistant Coach .................................404-894-9739 Director of Athletics Dave Braine (North Carolina ’65) Davidson ’88 (Second season at Tech) Enrollment 14,000 Willie Reese, Assistant Coach ................................. 404-894-9740 Founded 1885 Georgia Tech ’89 (Third season at Tech) Colors Old Gold and White Cliff Warren, Assistant Coach ................................. 404-894-9742 Mount St. Mary’s ’90 (Second season at Tech) Nickname Yellow Jackets, Rambling Wreck Peter Zaharis, Director of Operations ...................... 404-894-8318 Mascot Buzz (Yellow Jacket), 1930 Model A Ford New York University ’87 (Second season at Tech) Conference Atlantic Coast (ACC) Kisha Grimes, Administrative Assistant .....................404-894-5425 Home Arena Alexander Memorial Coliseum Christy Kaiser, Administrative Assistant................... 404-894-5478 at McDonald’s Center (9,191) Head Coach Paul Hewitt (St. John Fisher ’85) Record at Tech Second Year Overall Record 83-40 (.675), 4 years Georgia Tech Campus Information ...........................404-894-2000 Edge Athletic Center ............................................. 404-894-5400 Assistant Coaches Dean Keener Willie Reese Accounting Office..................................................404-894-5439 Cliff Warren Alexander-Tharpe -

Memphis Grizzlies 2016 Nba Draft

MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 2016 NBA DRAFT June 23, 2016 • FedExForum • Memphis, TN Table of Contents 2016 NBA Draft Order ...................................................................................................... 2 2016 Grizzlies Draft Notes ...................................................................................................... 3 Grizzlies Draft History ...................................................................................................... 4 Grizzlies Future Draft Picks / Early Entry Candidate History ...................................................................................................... 5 History of No. 17 Overall Pick / No. 57 Overall Pick ...................................................................................................... 6 2015‐16 Grizzlies Alphabetical and Numerical Roster ...................................................................................................... 7 How The Grizzlies Were Built ...................................................................................................... 8 2015‐16 Grizzlies Transactions ...................................................................................................... 9 2016 NBA Draft Prospect Pronunciation Guide ...................................................................................................... 10 All Time No. 1 Overall NBA Draft Picks ...................................................................................................... 11 No. 1 Draft Picks That Have Won NBA -

Talented Tenth W.E.B

November 2006 Volume 1, Issue 2 TALENTED TENTH W.E.B. Du Bois Poetry Corner, p. 7; NBA Season Preview, p. 9; UPCOMING Where are all the classy women?, p. 6 EVENTS Events @ the BCC blurred lens in November 7th Holocaust Lecture Series Against Cultural Genocide Documentary Feature: “From Swastika to Jim Crow” BCC Auditorium 12 Noon & 6 p.m. vandy’s vision November 9th The Return of MiCheck 8 p.m. - 10 p.m. BCC Auditorium November 15th “In the Black” Business Workshop and Discussion Featuring Roland Jones, McDonalds Franchise Owner 12 Noon November 29th, 4:10 PM Reception to Follow at the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities Sponsored by Black Europe/Black European Studies Reading Group & PAADS EVENTS IN NASHVILLE AREA The Lion King October 26 - December 3 Andrew Jackson Hall Come experience the phenomenon of Disney’s THE LION KING. Marvel at the breathtaking spectacle of animals brought to life by award-winning director Julie Taymor, whose visual images for this show you’ll remember forever. Thrill to the pulsating rhythms of the African Pridelands and an unforgettable score including Elton John and Tim Rice’s Oscar-winning song “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” and “Circle of Life.” Let your imagination run wild at the Vanderbilt Photo Archive Tony Award-winning Broadway sensation Newsweek calls “a landmark event in entertainment.” Nashville’s most eagerly awaited stage production ever will leap onto the TPAC stage every; week to talk about nothing this season. By: Corey Ponder caring, discovery, and celebration. at all is just bad…you learn more ASSOCIATE NEWS EDITOR Freshmen like Morgan Turner, College Sunday hosted by Mt.