Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

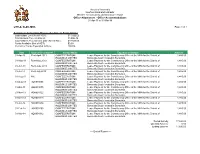

Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-13 to 31-Mar-14

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-13 to 31-Mar-14 LITTLE, GLEN, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2013/14 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $17,820.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-14 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $17,820.00 Funds Available (Net of HST): $0.00 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 100.0% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 01-Apr-13 Rent-April 2013 CONFEDERATION Lease Payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of 1,485.00 HOLDINGS LIMITED Bonavista South located in Bonavista. 01-May-13 Rent-May 2013 CONFEDERATION Lease Payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of 1,485.00 HOLDINGS LIMITED Bonavista South located in Bonavista. 01-Jun-13 Rent-June 2013 CONFEDERATION Lease Payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of 1,485.00 HOLDINGS LIMITED Bonavista South located in Bonavista. 01-Jul-13 Rent-July 2013 CONFEDERATION Lease Payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of 1,485.00 HOLDINGS LIMITED Bonavista South located in Bonavista. 01-Aug-13 986 CONFEDERATION Lease Payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of 1,485.00 HOLDINGS LIMITED Bonavista South located in Bonavista. 01-Sep-13 HOA001036 CONFEDERATION Lease Payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of 1,485.00 HOLDINGS LIMITED Bonavista South located in Bonavista. -

VE:Rbatl,M REPORT

,.. PROVINCE OF NEWFOUNDLAND THIRTY-SIXTH GENERAL ASSEM.BLY OF NEWFOUND.LAND Volume 3 3rd. Session Number 38 VE:RBATl,M REPORT MONDAY, APRIL 1, 1974 SPEAKER : THE HONOURABLE JAMES M. RUSSELL APRIL l, 1974 ~BCIAL SESSION TO MARK THE TWENTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF NEtn"OtJN])LANl)' S ENTRY INTO CONFEDERATION WITH CANADA Held at the House of Assembly, Colonial Building, Military Road St • .Jo}?.a's, Newfoundland The House met at 3:00 P.M., at the House of Assembly, Colonial Building. Mr. Speaker in the Chair. MR. SPEAKER: Order, please? HON. W.W. MARSHALL (MINIS';l'ER VITHOUT PORTFOLIO): Mr. Speaker, I move that the Orders of the Day be not read. Motion, that the Orders of the Day be not read, carried: MR. MARSHALL: Motion III, Mr. Speaker: On motion of the lion. the Minister of Touriem 1 a bill, "An Act Respecting The Colonial Building, "read a first time, ordered read a second ti.me now, by leave. MR. SPEAKER: The Hon. Minister of Tourism. HON. T. M, DOYLE (MINISTER OF TOURISM): Mr. Spealter, I have much pleasure in moving the second reading of this bill. It is deemed that the Colonial Building, of such historic significance, be declared a Provincial Historic Site for purposes in the future of restoring it to its period condition. It is our• hope that this will be done within three or four years time when hopefully the province will have a new Museum-Archives Complex. At that time, as I have said, this building will be restored further to its original condition and will be used as an historic site in the same manner as the Cable Station at Heart's Content will be used following this yearlll\d the Commissariat House on King's Bridge Road, as a tourist attraction. -

This Guide Was Prepared and Written by Roberta Thomas, Contract Archivist, During the Summer of 2000

1 This guide was prepared and written by Roberta Thomas, contract archivist, during the summer of 2000. Financial assistance was provided by the Canadian Council of Archives, through the Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Archives. This guide was updated by Pamela Hayter, October 6, 2010. This guide was updated by Daphne Clarke, February 8, 2018. Clarence Dewling, Archivist TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 List of Holdings ........................................................ 3 Business Records ...................................................... 7 Church and Parish Records .................................... 22 Education and Schools…………………………..52 Courts and Administration of Justice ..................... 65 Societies and Organizations ................................... 73 Personal Papers ..................................................... 102 Manuscripts .......................................................... 136 Index……………………………………………2 LIST OF THE HOLDINGS OF THE TRINITY 3 HISTORICAL SOCIETY ARCHIVES BUSINESS RECORDS Slade fonds, 1807-1861. - 84 cm textual records. E. Batson fonds, 1914 – 1974 – 156.40 cm textual records Grieve and Bremner fonds, 1863-1902 (predominant), 1832-1902 (inclusive). - 7.5 m textual records Hiscock Family Fonds, 1947 – 1963 – 12 cm textual records Ryan Brothers, Trinity, fonds, 1892 - 1948. – 6.19 m textual records Robinson Brooking & Co. Price Book, 1850-1858. - 0.5 cm textual records CHURCH AND PARISH RECORDS The Anglican Parish of Trinity fonds - 1753 -2017 – 87.75 cm textual records St. Paul=s Anglican Church (Trinity) fonds. - 1756 - 2010 – 136.5 cm textual records St. Paul’s Guild (Trinity) ACW fonds – 1900 – 1984 – 20.5 cm textual records Church of the Holy Nativity (Little Harbour) fonds, 1931-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. Augustine=s Church (British Harbour) fonds, 1854 - 1968. - 9 cm textual records St. Nicholas Church (Ivanhoe) fonds, 1926-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. George=s Church (Ireland=s Eye) fonds, 1888-1965. -

PUB-NLH-304 Island Interconnected System Supply Issues And

PUB‐NLH‐304 Island Interconnected System Supply Issues and Power Outages Page 1 of 1 1 Q. Provide a copy of the Joint Utilities Communications Plan established with 2 Newfoundland Power that outlines notification protocol during a system event. 3 4 5 A. A copy of the Joint Storm/Outage Communications Plan for Newfoundland Power 6 and Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro is attached as PUB‐NLH‐304 Attachment 1. PUB-NLH-304, Attachment 1 Page 1 of 92, Isl Int System Power Outages June 14 DRAFT of September 16, 2014 Joint Storm/Outage Communications Plan Newfoundland Power and Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro This plan reflects the cooperation and coordination between Newfoundland Power and Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro with respect to Storm/Outage Communications. 55 Kenmount Road, St. John’s, NL 1 PUB-NLH-304, Attachment 1 Page 2 of 92, Isl Int System Power Outages Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 4 AUTHORITY OF THE PLAN 4 PLAN ADMINISTRATION 4 STATEMENT OF JOINT UTILITY COOPERATION 4 OBJECTIVES 5 GUIDING PRINCIPLES 5 BACKGROUND 6 OVERVIEW OF THE PROVINCIAL ELECTRICITY SYSTEM 6 INTEGRATION AND COORDINATION WITH OTHER PLANS 6 INTER‐UTILITY OPERATION COORDINATION 7 TARGET AUDIENCE/KEY STAKEHOLDERS 7 FORTHRIGHT, SIMPLE TONE 8 THE PUBLIC, CUSTOMERS AND STAKEHOLDERS 8 EMPLOYEES AND CONTRACTORS 8 MEDIA 8 IDENTIFICATION OF TYPE AND SEVERITY OF OUTAGE 9 TYPES OF MAJOR OUTAGES 9 SEVERITY OF OUTAGES 9 OUTAGE SEVERITY LEVELS AND COMMUNICATIONS RESPONSE STRATEGIES 11 COMMUNICATIONS APPROACH AND TACTICS 12 NEWFOUNDLAND POWER’S COMMUNICATIONS HUB 13 COMMUNICATIONS -

City of St. John's Archives the Following Is a List of St. John's

City of St. John’s Archives The following is a list of St. John's streets, areas, monuments and plaques. This list is not complete, there are several streets for which we do not have a record of nomenclature. If you have information that you think would be a valuable addition to this list please send us an email at [email protected] 18th (Eighteenth) Street Located between Topsail Road and Cornwall Avenue. Classification: Street A Abbott Avenue Located east off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Abbott's Road Located off Thorburn Road. Classification: Street Aberdeen Avenue Named by Council: May 28, 1986 Named at the request of the St. John's Airport Industrial Park developer due to their desire to have "oil related" streets named in the park. Located in the Cabot Industrial Park, off Stavanger Drive. Classification: Street Abraham Street Named by Council: August 14, 1957 Bishop Selwyn Abraham (1897-1955). Born in Lichfield, England. Appointed Co-adjutor Bishop of Newfoundland in 1937; appointed Anglican Bishop of Newfoundland 1944 Located off 1st Avenue to Roche Street. Classification: Street Adams Avenue Named by Council: April 14, 1955 The Adams family who were longtime residents in this area. Former W.G. Adams, a Judge of the Supreme Court, is a member of this family. Located between Freshwater Road and Pennywell Road. Classification: Street Adams Plantation A name once used to identify an area of New Gower Street within the vicinity of City Hall. Classification: Street Adelaide Street Located between Water Street to New Gower Street. Classification: Street Adventure Avenue Named by Council: February 22, 2010 The S. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 86 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................96 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................94 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................95 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................96 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................98 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................99 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................96 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................96 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................98 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................96 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson................................98 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

589 PART I PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY Vol. 76 ST. JOHN's, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2001 No. 45 MINERAL

PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 76 ST. JOHN'S, FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2001 No. 45 MINERAL ACT situate near Crescent Lake, Central Nfldon map sheet 2E/ 5 N O T I C E Mineral Licence 6945M Published in accordance with regulation 62 of the held by Lafarge Gypsum Canada Inc. Mineral Regulations. situate near St.Fintans, Western Nfld on map sheet 12B/ 2 Mineral rights to the following mineral licences have reverted to the Crown: Mineral Licence 7494M held by Michael R. Stacey Mineral Licence 4782 situate near Carrols Hat, Southern Nfld held by Altius Resources Inc. on map sheet 1M/15 situate near South Twin Lake, Central Nfld on map sheet 2E/ 5 Mineral Licence 7593M ,7594M ,7595M held by Buchans River Ltd Mineral Licence 402M situate near Morgan Arm, Southern Nfld held by Kennecott Canada Exploration Inc. on map sheet 1M/13 situate near Fraser Lake on map sheet 13L/ 5 Mineral Licence 7597M held by Pathfinder Exploration Ltd Mineral Licence 5637M situate near Arnolds Cove, Eastern Nfld held by Ascot Resources Ltd. on map sheet 1N/13, 1N/12 situate near Northeast of Harp Lake on map sheet 13N/ 6 Mineral Licence 8157M, 8158M held by William Mercer Mineral Licence 5638M, 5654M situate near Middleton Lake, Central Nfld held by Braithwaite Minerals Inc. on map sheet 2E/ 4 situate near Burin, Burin Peninsula on map sheet 1M/ 3 Claim block 17614, 17616 held by Altius Resources Inc. Mineral Licence 7400M, 7401M being part of licence 4783 held by Celtic Minerals Ltd situate near South Twin Lake, Central Nfld situate near Mary March Brook, Central Nfld on map sheet 2E/ 5 on map sheet 12A/16 A portion of licence 7774M Mineral Licence 6152M held by Altius Resources Inc. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 85 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2010 No. 5 JUDICATURE ACT RULES OF THE SUPREME COURT, 1986 PRACTICE NOTE P.N. (TD) NO. 2008-03 DATE ISSUED: November 20, 2008 RULES AFFECTED: 56C EFFECTIVE DATE: December 1, 2008 The following Practice Note was filed with the Registrar, as Secretary to the Rules Committee of the Trial Division, and is published pursuant to rule 4.04 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland & Labrador, 1986: FAMILY JUSTICE SERVICES DIVISION MEDIATION OF SPOUSAL SUPPORT MATTERS Background 1. The Family Justice Service Division, (FJSD) was established Province-wide on March 1, 2007. F.J.S.D. operates as an adjunct to the Supreme Court of Newfoundland & Labrador, Trial Division and the Provincial Court of Newfoundland & Labrador providing mandatory parent information sessions, mediation and counseling in family law matters involving custody, access and support issues, including spousal support. F.J.S.D. operates within Rule 56C of the Rules of the Supreme Court 1986 as amended. 33 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE February 5, 2010 2. Recently, for various reasons and after consultation with the various partners involved in F.J.S.D., a decision has been made by the Provincial Advisory Committee of F.J.S.D. to suspend the mediation of spousal support matters from the mandate of F.J.S.D. This initiative is a suspension only and it is contemplated that spousal support will once again be mediated in the future. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly

The Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly Alex Marland The purpose of this paper is to describe and analyze the Newfoundland and Labrador House of Assembly to increase public awareness of its procedural functions and provide the basis for a comparative analysis with other legislatures. The article includes a history of the legislature; the socio-demographics of MHAs; the resources of MHAs and party caucuses; and the relationship between government and opposition. The analysis includes the role of the Speaker, legislative committees, the procedure for bills, and the difficulties of mounting an effective opposition amidst lopsided majority governments. t is said that the Newfoundland and Labrador choice to election officials. The governor and seven House of Assembly has probably been the scene appointees comprised the upper house, known as the of more political and constitutional crises than all Legislative Council. These unelected men held political I 1 other provincial legislatures combined. The path to control and made spending decisions for the island’s 75 democratic government in Newfoundland, like many thousand residents, but they were required to consider of its highways, has been a bumpy, winding and foggy the views of the elected members. The nine electoral journey. The European-influenced political era began districts were located only on the eastern side of the when fishermen arrived in the late 15th century. Until island on the Avalon, Bonavista and Burin peninsulas. 1610 the area was “a kind of no man’s land, without -

Candidates Valued at Greater Than $100 2011 General Election Campaign

POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES VALUED AT GREATER THAN $100 2011 GENERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTOR CITY/TOWN/PROVINCE CANDIDATE/PARTY DISTRICT AMOUNT 10122 Newfoundland Ltd. Happy Valley - Goose Bay, NL Russell, Keith (PC) Lake Melville 500.00 10280 Newfoundland Limited Clarenville, NL Wiseman, Ross (PC) Trinity North 750.00 10418 Newfoundland Inc. St. Anthony, NL Dean, Marshall (Lib) The Straits - White Bay North 100.00 10418 Newfoundland Inc. St. Anthony, NL Pike, Selma (PC) The Straits - White Bay North 100.00 10488 Newfoundland Limited Carbonear, NL Kennedy, Jerome P. (PC) Carbonear - Harbour Grace 500.00 10547 Newfoundland Inc. Mount Pearl, NL Kent, Steve (PC) Mount Pearl North 250.00 10565 Nfld. Inc. Happy Valley - Goose Bay, NL Pottle, Patty (PC) Torngat Mountains 1,000.00 10565 Nfld. Inc. Happy Valley - Goose Bay, NL Russell, Keith (PC) Lake Melville 5,000.00 10657 Newfoundland Limited Grand Falls - Windsor, NL Hunter, Ray (PC) Grand Falls - Windsor - Green Bay South 200.00 10981 Newfoundland Limited St. John's, NL Dalley, Derrick (PC) The Isles of Notre Dame 500.00 11092 Newfoundland Inc. Clarenville, NL Wiseman, Ross (PC) Trinity North 750.00 11110 Newfoundland Limited Carbonear, NL Kennedy, Jerome P. (PC) Carbonear - Harbour Grace 250.00 11130 Nfld Ltd. Springdale, NL Pollard, Kevin (PC) Baie Verte - Springdale 500.00 11336 Newfoundland Inc. St. John's, NL Joyce, George (Lib) St. John's West 500.00 11336 Newfoundland Inc. St. John's, NL Kent, Steve (PC) Mount Pearl North 500.00 2001 Investments Limited Mount Pearl, NL Dumaresque, Danny Wade (Lib) The Isles of Notre Dame 1,000.00 4338553 Canada Inc. -

Bishop, D 26-MAR-19

Purchase Order No. Revision No. Page No. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador 216003669 3 1 Public Procurement Agency SHIP TO: As indicated in blanket release or 30 Strawberry Marsh Rd. contract agreement PO St. John's NL Canada A1B 4R4 TO: MICHAEL LABONTE & MARK DOWNEY o/a Technoto BILL TO: As indicated in blanket release PO Box 531 or 108 Sheldon Drive contract agreement PO Bay Bulls, NL Canada A0A 1C0 Canada Customer No. Supplier No. Ordered / Buyer Revised / Buyer 40146751 19-APR-16 Blanks, S 26-MAR-19 Bishop, D F.O.B: Requestor: Contact: DESTINATION Effective Start Date Effective End Date Amount Agreed (CAD) 01-MAY-2016 30-APR-2019 IMPORTANT: Document valid ONLY if NAME and DATE are present in "Authorized By" section. AUTHORIZED BY: Bishop, D DATE: 26-MAR-19 TOTAL: Line Item No./Description Promised Date Quantity / Unit Price Extended Tax NO: UOM MSOA # 216003669, Revision # 3 created to renew for one (1) additional month, expiry April 30, 2019. MSOA # 216003669, Revision # 2 created to exercise renewal option. MSOA # 216003669, Revision # 1 created to exercise renewal option. ---------------------------------- DATA WIRING SERVICES (Government Occupied Offices) MASTER STANDING OFFER AGREEMENT The resulting Standing Offer Agreement shall permit any Government Department, and any Government Funded Body having delegated its authority to tender to the Central Purchasing Authority, to order, on an "as and when required basis", the items listed herein at the prices set against each. This ITT shall form part of the contract. PERIOD OF CONTRACT: The term of the Agreement shall be May 1, 2016 to March 31, 2019.