Spin Hall Effect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spin Hall Angles in Solids Exhibiting a Giant Spin Hall Effect

Spin Hall Angles in Solids Exhibiting a Giant Spin Hall Effect BROWN Jamie Holber Thesis Advisor: Professor Gang Xiao Department of Physics Brown University A thesis submitted in fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Physics April 2019 Abstract The Spin Hall Effect enables the conversion of charge current into spin current and provides a method for electrical control of the magnetization of a ferromagnet, enabling future applications in the transmission, storage, and control of information. The experimental values found for the Spin Hall Angle (ΘSH ), a way of quantifying the Spin Hall Effect in a nonmagnetic material, are studied in this thesis in regards to a variety of parameters including the atomic number, the fullness of the orbital, the spin diffusion length, thin film thickness, resistivity, temperature, and composition of alloys. We observed that the spin Hall angle dependence on atomic number, the fullness of the orbital, the spin diffusion length, and the resistivity aligned with the theory. The dependence on thickness and temperature was found to vary based on the material and more research is needed to determine larger trends. We found that alloys provide opportunities to create materials with large spin hall angles with lower resistivities. In particular, Au alloyed with other elements is a promising candidate. i Acknowledgements Thanks to my advisor, Professor Gang Xiao for his time and guidance working on my thesis. I would also like to thank the other members of my lab group who helped me and helped work on the project, Lijuan Qian, Wenzhe Chen, Guanyang He, Yiou Zhang, and Kang Wang. -

Week 10: Oct 27, 2016 Preamble to Quantum Hall Effect: Exotic

Week 10: Oct 27, 2016 Preamble to Quantum Hall Effect: Exotic Phenomenon in Quantum Physics The quantum Hall effect is one of the most remarkable of all quantum-matter phenomena, quite unanticipated by the physics community at the time of its discovery in 1980. This very surprising discovery earned von Klitzing the Nobel Prize in physics in 1985. The basic experimental observation is the quantization of resistance, in two-dimensional systems, to an extreme precision, irrespective of the sample’s shape and of its degree of purity. This intriguing phenomenon is a manifestation of quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale, and for that reason, it rivals superconductivity and Bose–Einstein condensation in its fundamental importance. As we will see later in this class, that this effect is an example of Berry phase and the “quanta” that appear in the quantization of Hall conductivity are the topological integers that emerge from quantum analog of Gauss-Bonnet theorem. This years Nobel prize to David Thouless is for explaining this exotic quantization in terms of topology. It turns out that the classical and quantum anholonomy are described by the same mathematics. To understand that, we need to introduce the concept of “curvature. As we know, it is the curved space that leads to anholonomy in classical physics. This allows us to define curvature in quantum physics. That is, using the concept of anholonomy in quantum physics, we can define the concept of curvature in quantum physics – that is, in Hilbert space. Curvature leads us to Topological Invariants that tells us that anholonomy may have its roots in topology. -

S-Electron Ferromagnetism in Gold and Silver Nanoclusters

NANO LETTERS 2007 s-Electron Ferromagnetism in Gold and Vol. 7, No. 10 Silver Nanoclusters 3134-3137 Weidong Luo,*,†,‡ Stephen J. Pennycook,‡ and Sokrates T. Pantelides†,‡ Department of Physics and Astronomy, Vanderbilt UniVersity, NashVille, Tennessee 37235, and Materials Science and Technology DiVision, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 Received July 12, 2007 ABSTRACT Ferromagnetic (FM) ordering in transition-metal systems (solids, surface layers, nanoparticles) arises from partially filled d shells. Thus, recent observations of FM Au nanoclusters was unexpected, and an explanation has remained elusive. Here we report first-principles density- functional spin-polarized calculations for Au and Ag nanoclusters. We find that the highest-occupied level is highly degenerate and partially filled by s electrons with spins aligned according to Hund’s rule. The nanoclusters behave like “superatoms”, with the spin-aligned electrons being itinerant on the outer shell of atoms. Ferromagnetism in bulk Fe, Co, and Ni originates from shells is crucial to achieve FM ordering. The case of Au partially filled 3d shells. In contrast, transition metals in the nanoparticles is particularly intriguing because the d orbitals 4d and 5d series do not exhibit FM ordering. The difference are completely full and bulk Au is diamagnetic. Hori et al.8,9 has been explained by the Stoner theory of itinerant electron reported that Au nanoparticles capped by a polymer exhibit magnetism.1 A combination of large density-of-states at the ferromagnetism (the presence of transition-metal impurities Fermi energy, NF, and a large Stoner exchange constant I is with partially filled d shells was ruled out), whereas Crespo essential. -

Magnetism on the Nanoscale I

Joseph Dufouleur, Quantum Transport Group, [email protected] Magnetism on the nanoscale I. What is spintronics? 1. A brief introduction Conventional electronic: manipulate the charge of the electron. One of the most important technological projection of the second half of the 20th century. Few decades after the discovery of the transistor (1947) ⇓ manipulate the spin of the charge carrier instead of its charge: ⟶ improve many different properties of the electronic/spintronc devices ⟶ explore new functionalities of spintronic devices. For instance: •using ferromagnet-based electronics ⟶ very stable memory (M-RAM) and devices with very fast switching properties. •It was demonstrated that heterostructures of semiconductors and ferromagnetic metals can be used to build a spin-polarized light emitting diode. •As a prospective aim: spin transistor: (https://slideplayer.com/slide/5189531/) •to be able to manipulate one single spin as a q-bit would be a great achievement on the way of building a quantum computer. commercial applications following discoveries in spintronics field: •GMR (Fert and Grünberg, Nobel prize in 2007) or TMR: Magnetic field sensors. In 2008, the term GMR appeared in more than 1500 US patents! •TMR: Read heads of magnetic hard disk drives and non-volatils random access memory. •Spin injection -> polarized LED, ... Principle: interaction ferromagnet spin of the conduction electrons - spin polarized a current (spin injection) - orientation of the magnetization determine the current flow ie. the resistance - the current flow can influence the orientation of the magnetization -> „Spin transfer torque“ Key points for building spintronic devices: • To be able to inject spins into a device or, equivalently, to create a spin current by polarizing for instance a charge current. -

Direct Observation of High Spin Polarization in Co2feal Thin Films

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Direct observation of high spin polarization in Co2FeAl thin flms Xiaoqian Zhang1, Huanfeng Xu1, Bolin Lai1, Qiangsheng Lu2,3, Xianyang Lu 4, Yequan Chen1, Wei Niu1, Chenyi Gu5, Wenqing Liu1,4, Xuefeng Wang 1, Chang Liu2, Yuefeng Nie5, Liang He1 1,4 Received: 11 December 2017 & Yongbing Xu Accepted: 3 April 2018 We have studied the Co2FeAl thin flms with diferent thicknesses epitaxially grown on GaAs (001) by Published: xx xx xxxx molecular beam epitaxy. The magnetic properties and spin polarization of the flms were investigated by in-situ magneto-optic Kerr efect (MOKE) measurement and spin-resolved angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (spin-ARPES) at 300 K, respectively. High spin polarization of 58% (±7%) was observed for the flm with thickness of 21 unit cells (uc), for the frst time. However, when the thickness decreases to 2.5 uc, the spin polarization falls to 29% (±2%) only. This change is also accompanied by a magnetic transition at 4 uc characterized by the MOKE intensity. Above it, the flm’s magnetization reaches the bulk value of 1000 emu/cm3. Our fndings set a lower limit on the thickness of Co2FeAl flms, which possesses both high spin polarization and large magnetization. Spintronic devices rely on thin layers of magnetic materials, for they are designed to control both the charge and the spin current of the electrons. Half-metallic ferromagnets (HMFs) have only one spin channel for conduction at the Fermi level, while they have a band gap in the other spin channel1–4. Terefore, in principle this kind of material has 100% spin polarization for transport, which is perfect for spin injection, spin fltering, and spin trans- fer torque devices5. -

Topological Insulators Physicsworld.Com Topological Insulators This Newly Discovered Phase of Matter Has Become One of the Hottest Topics in Condensed-Matter Physics

Feature: Topological insulators physicsworld.com Topological insulators This newly discovered phase of matter has become one of the hottest topics in condensed-matter physics. It is hard to understand – there is no denying it – but take a deep breath, as Charles Kane and Joel Moore are here to explain what all the fuss is about Charles Kane is a As anyone with a healthy fear of sticking their fingers celebrated by the 2010 Nobel prize – that inspired these professor of physics into a plug socket will know, the behaviour of electrons new ideas about topology. at the University of in different materials varies dramatically. The first But only when topological insulators were discov- Pennsylvania. “electronic phases” of matter to be defined were the ered experimentally in 2007 did the attention of the Joel Moore is an electrical conductor and insulator, and then came the condensed-matter-physics community become firmly associate professor semiconductor, the magnet and more exotic phases focused on this new class of materials. A related topo- of physics at University of such as the superconductor. Recent work has, how- logical property known as the quantum Hall effect had California, Berkeley ever, now uncovered a new electronic phase called a already been found in 2D ribbons in the early 1980s, and a faculty scientist topological insulator. Putting the name to one side for but the discovery of the first example of a 3D topologi- at the Lawrence now, the meaning of which will become clear later, cal phase reignited that earlier interest. Given that the Berkeley National what is really getting everyone excited is the behaviour 3D topological insulators are fairly standard bulk semi- Laboratory, of materials in this phase. -

Introduction to Spin Hall Effect Spin-Dependent Lorentz Force Our

The spin Hall effect in a quantum gas M. C. Beeler*, R. A. Williams, K. Jimenez-Garcia, L. J. LeBlanc, A. R. Perry, I. B. Spielman Joint Quantum Institute, National Institute of Standards and Technology and Department of Physics, University of Maryland, Gaithersburg, MD 20899, USA Introduction to spin Hall effect Our system Spin currents Vector potential gradient • Spin Hall effect is separation of Vector potential is electron spins perpendicular to current proportional to flow coupling strength (intensity) • No external magnetic field needed – spin-orbit coupling drives effect Adjust equilibrium Current Flow Current position of BEC along • Effect is integral for spintronic devices Gaussian intensity and topological insulators gradient of Raman Color indicates predominant spin composition.1 beams 87 • Rb atoms in F = 1 ground state, confined in 90° cross-beam This is the first observation of the spin Hall effect in a optical dipole trap (ODT) Snapping off Raman cold atom system. beams gives electric • λ =790.21 nm Raman beams (Δω/2π = 15 MHz) couple mF = 0 field kick Spin-Dependent Lorentz Force and mF = -1 spin states, with large bias magnetic field along ez In intensity gradient, Lorentz Force • Adjustment of acousto-optic modulator frequency allows kick is spatially 퐹 = force dynamic control of BEC y-position by displacing one ODT beam dependent, shearing 퐹 = 푞 v × 퐵 q = charge the cloud after 2 v = velocity • No crystal structure, but system has spin-orbit coupling expansion • Cross product means that 퐵 = magnetic field particles always move • Atoms play the role of electrons, with spin coupling to linear Shear is opposite for perpendicular to velocity and 퐵 momentum along ex two pseudo-spins field. -

Effect of Spin Polarization on the Structural Properties and Bond Hardness of Fexb(X = 1, 2, 3) Compounds first-Principles Study

Bull. Mater. Sci., Vol. 39, No. 6, October 2016, pp. 1427–1434. c Indian Academy of Sciences. DOI 10.1007/s12034-016-1263-2 Effect of spin polarization on the structural properties and bond hardness of FexB(x = 1, 2, 3) compounds first-principles study AHMED GUEDDOUH1,2,∗, BACHIR BENTRIA1, IBN KHALDOUN LEFKAIER1 and YAHIA BOUROUROU3 1Laboratoire de Physique des Matériaux, Université Amar Telidji de Laghouat, BP37G, Laghouat 03000, Algeria 2Département de Physique, Faculté des Sciences, Université A.B. Belkaid Tlemcen, BP 119, Tlemcen 13000, Algeria 3Modeling and Simulation in Materials Science Laboratory, University of Sidi Bel-Abbès, 22000 Sidi Bel-Abbès, Algeria MS received 14 November 2014; accepted 17 March 2016 Abstract. In this paper, spin and non-spin polarization (SP, NSP) are performed to study structural properties and bond hardness of Fex B(x = 1, 2, 3) compounds using density functional theory (DFT) within generalized gradient approximation (GGA) to evaluate the effect of spin polarization on these properties. The non-spin-polarization results show that the non-magnetic state (NM) is less stable thermodynamically for Fex B compounds than spin- polarization by the calculated cohesive energy and formation enthalpy. Spin-polarization calculations show that ferromagnetic state (FM) is stable for Fex B structures and carry magnetic moment of 1.12, 1.83 and 2.03 μBinFeB, Fe2BandFe3B, respectively. The calculated lattice parameters, bulk modulus and magnetic moments agree well with experimental and other theoretical results. Significant differences in volume and in bulk modulus were found between the ferromagnetic and non-magnetic cases, i.e., 6.8, 32.8%, respectively. -

Observation of the Magnon Hall Effect

Observation of the magnon Hall effect [One-sentence summary] We have observed the Hall effect of magnons for the first time in terms of transverse thermal transport in a ferromagnetic insulator Lu2V2O7 with pyrochlore structure. Y. Onose,1,2 † T. Ideue,1 H. Katsura, 3 Y. Shiomi,1,4 N. Nagaosa,1, 4 and Y. Tokura1, 2, 4 1Department of Applied Physics, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8656, Japan 2 Multiferroics Project, ERATO, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), c/o Department of Applied Physics, University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8656, Japan 3Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA 4Cross-Correlated Materials Research Group (CMRG) and Correlated Electron Research Group (CERG), Advanced Science Institute, RIKEN, Wako,351-0198, Japan † To whom correspondence should be addressed E-mail: [email protected] [abstract] The Hall effect usually occurs when the Lorentz force acts on a charge current in a conductor in the presence of perpendicular magnetic field. On the other hand, neutral quasi-particles such as phonons and spins can carry heat current and potentially show the Hall effect without resorting to the Lorentz force. We report experimental evidence for the anomalous thermal Hall effect caused by spin excitations (magnons) in an insulating ferromagnet with a pyrochlore lattice structure. Our theoretical analysis indicates that the propagation of the spin wave is influenced by the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya spin-orbit interaction, which plays the role of the vector potential as in the intrinsic anomalous Hall effect in metallic ferromagnets. [text] Electronics based on the spin degree of freedom, (spintronics), holds promise for new developments beyond Si-based-technologies (1), and avoids the dissipation from Joule heating by replacing charge currents with currents of the magnetic moment (spin currents). -

Spin-Polarized Exotic Nuclei

Spin-polarized exotic nuclei: from fundamental interactions, via nuclear structure, to biology and medicine Magdalena Kowalska UNIGE and CERN Outline Decay of polarized nuclei Spin polarization with lasers Spin-polarized radioactive nuclei in: Fundamental physics Nuclear physics NMR in biology MRI in medicine Summary and outlook 2 Decay of spin-polarized nuclei Beta and gamma decay of spin-polarized nuclei anisotropic in space Beta decay, I>0 Gamma decay, I>1/2 B0 푊 휃푟 = 1 + 푎1cos(휃푟) a1=P ab depend on degree and order of spin polarization and transition details (initial spin, change of spin) Observed decay asymmetry can be used to: Probe underlying decay mechanism (GT) Determine properties of involved nuclear states Derive differences in nuclear energy levels3 Spin polarization via optical pumping Multiple excitation cycles with circularly-polarized laser light Photon angular momentum transferred to electrons and then nuclei Works best for 1 valence electron nuclear spin-polarization of 10-90% Polarization buildup time < us fine structure hyperfine structure Magnetic sublevels 3p 2P 3 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 3/2 2 1 0 F 29Mg + I =3/2 D2-line s+ light 2 -2 -1 0 1 2 2 3s S1/2 1 frequency 4 Optical pumping and nuclear spins Polarization of atomic spins leads to polarization of nuclear spins via hyperfine interaction (PF->PI) Decoupling of electron (J) and nuclear (I) spins in strong magnetic field Observation of nuclear spin polarization PI possible Magnetic field B 3p 2P 3 3/2 2 1 0 Dm = +1 for s+ or -1 for s- light 29Mg F I =3/2 3/2 -

Dynamic Nuclear Polarization for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: an In-Bore Approach

Dynamic Nuclear Polarization for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: An In-bore Approach Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften vorgelegt beim Fachbereich 14 der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universit¨at in Frankfurt am Main von Jan G. Krummenacker aus V¨olklingen Frankfurt, 2012 D30 vom Fachbereich 14 der Johann-Wolfgang Goethe-Universit¨atals Dissertation angenommen. Dekan: Prof. Dr. Thomas F. Prisner Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Thomas F. Prisner, Prof. Dr. Laura M. Schreiber Datum der Disputation: Contents 1 Introduction 7 2 Theoretical Background 11 2.1 NMR Basics . 11 2.1.1 The Zeeman Term: Thermal Polarization . 12 2.1.2 Magnetization . 15 2.1.3 The RF Term: Manipulation of Magnetizations . 16 2.1.4 The Bloch Equations . 17 2.1.5 NMR Experiments . 18 2.2 EPR Basics . 21 2.2.1 EPR Spectrum of TEMPOL . 23 2.3 Dynamic Nuclear Polarization . 25 2.3.1 The Overhauser Effect . 25 2.3.2 Leakage Factor . 28 2.3.3 Saturation Factor . 29 2.3.4 Coupling Factor . 31 2.3.5 DNP in Solids . 34 3 Liquid State DNP at High Fields 37 3.1 Hardware . 37 3.1.1 The DNP Spectrometer . 38 3.1.2 Microwave Sources . 40 3.1.3 Power Transmission . 41 3.1.4 Experimental Procedures . 41 3.2 Experimental Results . 43 3.2.1 DNP on Water . 43 3.2.2 DNP on Organic Solvents . 53 3.2.3 Beyond Solvents: DNP on Metabolites . 56 3.3 Conclusion and Outlook . 62 3 4 CONTENTS 4 DNP for MRI 63 4.1 Other Hyperpolarization Methods . 63 4.1.1 PHIP . -

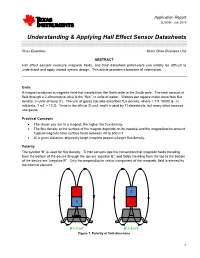

Understanding & Applying Hall Effect Sensor Datasheets

Application Report SLIA086 – July 2014 Understanding & Applying Hall Effect Sensor Datasheets Ross Eisenbeis Motor Drive Business Unit ABSTRACT Hall effect sensors measure magnetic fields, and their datasheet parameters can initially be difficult to understand and apply toward system design. This article provides a baseline of information. Units A magnet produces a magnetic field that travels from the North pole to the South pole. The total amount of field through a 2-dimensional slice is the “flux”, in units of weber. Webers per square meter describes flux density, in units of tesla (T). The unit of gauss (G) also describes flux density, where 1 T = 10000 G. In millitesla, 1 mT = 10 G. Tesla is the official SI unit, and it’s used by TI datasheets, but many other sources use gauss. Practical Concepts The closer you are to a magnet, the higher the flux density. The flux density at the surface of the magnet depends on its material and the magnetization amount. Typical magnets have surface fields between 40 to 600 mT. At a given distance, physically large magnets project a larger flux density. Polarity The symbol “B” is used for flux density. TI Hall sensors use the convention that magnetic fields traveling from the bottom of the device through the top are “positive B”, and fields traveling from the top to the bottom of the device are “negative B”. Only the perpendicular vector component of the magnetic field is sensed by the internal element. N S S N B > 0 mT B < 0 mT Figure 1. Polarity of field directions 1 Digital Hall Sensor Functionality Digital Hall Sensor Functionality Digital Hall sensors have an open-drain output that pulls Low if B exceeds the threshold BOP (the Operate Point).