So You Want to Start a Campus Food Pantry? a How-To Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Warmth & Quality of Pine Furniture

The Warmth & Quality Of Pine Furniture 1 #85 Cradle #76 Single Swing #84 Doll Bed #93 Giraffe #92 Small #77 Double Swing Clothes Tree #90 Bread Box #83 Bunk Bed #80 Stroller #81 Highchair #86 Doll Chest #91 Plain Bread Box C G B F A E H K D #101 Knotty Pine Peg Shelves #101 Knotty Pine Plain Shelves 2 D C C B B A A #102 Quilt Shelves #103 Peg Rack #123 DVD Rack #105 Airplane Shelf #270 Mini Bench #153 Outhouse #113 Two Door Wall Cabinet #114 Two Door with Mirror #118 House Bookshelf #119 Barn Bookshelf #122 Country Bookshelf 3 #125 Coffee Table Bench #128 - 5' Sofa Table #151 Step Stool Also Available In 3' & 4' With One Drawer #129 - 4' Hall Table Also available in 2' & 3' #130 - 3' Box Table #131 Box Table with Drawer #132 Box Table #133 Half Round Table #134 Corner Table #137 Large Round Table #141A Large Plant Stand #755 Medium Plant Stand with Drawer 4 #145 - 15" Plant Stand #147 Small Veggie Bin #146 - 22" Sofa Table #148 Large Veggie Bin #156 Quilt Rack #162 Pull out Trash Bin #157 Picket Bench #161 Trash Bin with Drawer #163 Hamper #169 Corner TV 5 #165 One Door Cabinet #168 Phone Stand #171 Small Microwave Stand #178A Large Clothes Rack #178B Small Clothes Rack #172 Three Shelf Wide Picket #174 Four Shelf Wide Picket #173 Three Shelf Narrow Picket #175 Four Shelf Narrow Picket #179 Table & Chair Set #191 Large Microwave Stand #192 Hoosier Cabinet 6 #193 Country Hoosier Cabinet #200 Glass Door Corner Hutch #208 Large Hall Bench A A B B C C #272 Narrow Top Peg Shelf #274 Plain Narrow Top Shelf #275 Rustic Chest #275A Primitive Chest -

Pantry Name Hours of Operation Pantry Address Supplies Phone Tuesday 12-3 Emergency Also Catholic Charities Pantry 120 W

SHIAWASSEE COUNTY AREA FOOD PANTRIES Pantry Name Hours of Operation Pantry Address Supplies Phone Tuesday 12-3 emergency also Catholic Charities Pantry 120 W. Exchange #300 Owosso Food, personal care, linens 989-723-8239 Friday 9-12 Corunna Ministerial/ Corunna United 10-12 Thursdays only 200 W McArthur, Corunna Food, Cold items 989-743-5050 Methodist Church First Church of God-Loving Hands Call for Appt. 2100 N M-52 Owosso Food & Funds 989-723-4510 pantry GCC - Gaines St Joseph Wednesday by appt. only 12145 Ray Rd. Gaines Food, Personal Items 810-399-4752 810-621-3202 Lennon Call for appt. Leave name and 1014 Oak St, Lennon Food, personal care 810-621-3676 Community Food Pantry number 810-621-4285 7495 Orchard St New Lothrop Methodist Food Pantry Thursday 9-12 Food and Paper products 810-638-5702 New Lothrop Outreach Center - Christ Episcopal Every Thursday 11-1 Food, clothing, household 120 E Goodhue St. Owosso, 989-723-2495 Church items, personal care items Mon-Fri 9-3:30 Office perishable and non perishable Salvation Army 302 W Exchange Owosso 989-725-7485 MWF 1-3 Pantry food, soup kitchen Shiawassee Council on Aging - Call 723-8875 hot meals & delivered hot 300 N Washington St, Owosso 989-723-8875 SENIORS ONLY M-F 8:30-5 meals 322 Dutcher Rd PO Box 113, Non food, Hygiene and Shiawassee Harvest Ministries Thursday 10am-12 noon 989-743-4091 Corunna cleaning products Food, Hygiene, blankets, hats Shiawassee United Way M-W 10-3 123 S Washington St., Owosso 989-723-4987 and mittens 989-666-2734 St John's United Church of Christ 3rd Tuesday 1-4pm 429 N Washington, Owosso Food 989-277-4849 Trinity United Methodist -Father's On call 24/7 720 S Shiawassee St., Owosso Food 989-721-1609 Cupboard Vernon Lighthouse Pentecostal Church Call for Appt 201 E Washington St, Vernon Food, personal care 989-743-5497 Diapers, Baby Food, Formula, Baby Pantry 2ND & 4TH Monday 11-7 114 W Mason, Owosso 989-723-5877 Baby items, Clothing St Vincent De Paul 7pm Tuesdays 111 N Howell, Owosso Food, Financial and clothing 989-723-4277 Perry, Morrice, Shaftsburg Emergency Call for Appt. -

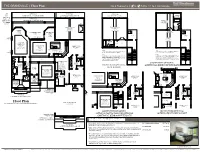

Floor Plan 3 to 4 Bedrooms | 2 2 to 3 2 Baths | 2- to 3-Car Garage

1 1 THE GRANDVILLE | Floor Plan 3 to 4 Bedrooms | 2 2 to 3 2 Baths | 2- to 3-Car Garage OPT. OPTIONAL OPTIONAL OPTIONAL WALK-IN EXT. ADDITIONAL COVERED LANAI EXPANDED FAMILY ROOM EXTERIOR BALCONY CLOSET PRIVACY WALL AT OPTIONAL ADDITIONAL EXPANDED COVERED LANAI BEDROOM 12'8"X12'6" COVERED VAULTED CLG. OPT. LANAI FIREPLACE FAMILY ROOM BONUS ROOM BATH VAULTED 21'6"X16' 18'2"X16'1" CLG. 9' TO 10' SITTING 10' TO 13'1" VAULTED CLG. VAULTED CLG. OPTIONAL AREA COVERED LANAI A/C DOUBLE DOORS A/C 10' CLG. BREAKFAST 10' CLG. AREA 9'X8' MECH. MECH. 10' CLG. OPT. SLIDING OPT. GLASS DOOR LOFT WINDOW 18'2"X13' 9' TO 10' BATH VAULTED CLG. MASTER 9' CLG. 9' CLG. BEDROOM CLOSET 22'X13'4" 10' CLG. LIVING ROOM BEDROOM 2 DW OPT. 10' TO 10'8" 14'X12' 11'8"X11'2" 10' CLG. COFFERED CLG. 10' CLG. DN OPT. 10' TO 10'8" GOURMET KITCHEN DN COFFERED CLG. NOTE: NOTE: OPT. 14'4"X13' MICRO/ THIS OPTION FEATURES AN ADDITIONAL 483 SQ. THIS OPTION FEATURES AN ADDITIONAL 560 SQ. WINDOW 10' CLG. WALL FT. OF AIR CONDITIONED LIVING AREA. FT. OF AIR CONDITIONED LIVING AREA. OVEN REF. NOTE: NOTE: PANTRY SPACE OPTION 003 INTERIOR WET BAR, 008 DRY BAR, 021 CLOSET OPTION 003 INTERIOR WET BAR, 008 DRY BAR, 032 ADDITIONAL BEDROOM WITH BATH, 806 BONUS ROOM, 806 ALTERNATE KITCHEN LAYOUT, ALTERNATE KITCHEN LAYOUT, AND 812 BUTLER AND 812 BUTLER PANTRY CANNOT BE 10' CLG. 10' CLG. PANTRY CANNOT BE PURCHASED IN PURCHASED IN CONJUNCTION WITH THIS OPTION. -

2021 TEFAP Pantry and Kitchen Distributions for Kent County

2021 TEFAP Pantry and Kitchen Distributions for Kent County Residents **This institution is an equal opportunity provider.** These sites below are community partners of The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) and offer TEFAP items in their Pantry or Kitchen. For changes in hours, days, and operations due to COVID-19 community response, please contact the pantry or kitchen before going to the site directly. Pantries: Baxter Community Center - Marketplace, 935 Baxter St SE, Grand Rapids, MI 616-456-8593 Distribution Times: Monday through Friday 10 AM- 5 PM; Byron Community Ministries, 8250 Byron Creek Dr., Byron Center, MI 616-878-6000 Distribution Times: Monday 3-5 PM; Wednesday 11 AM-2 PM ONLY in the months of February, May, August and November Eastern Ave Christian Reformed Church, 514 Eastern Ave SE, Grand Rapids MI 616-454-4888 Distribution Times: Fridays 12 PM-3 PM Family Network of Wyoming, 1029 44th St SW, Wyoming, MI 616-885-9919 Distribution Times: Monday 2:30-5 PM; Wednesday 1:30-7 PM Flat River Outreach Ministries (FROM), 11535 Fulton St E., Lowell, MI 616-897-8260 Distribution Times: Tuesday 2-4 PM; Wednesday 5-7 PM; Friday 10 AM- Noon Holy Spirit Episcopal Church- The Loaves & Fishes Food Pantry 616-784-1111 1200 Post Dr NE, Belmont MI Distribution Times: Thursday from 6-7:30 PM Page 1 of 4 2021 TEFAP Pantry and Kitchen 2021 TEFAP Pantry and Kitchen Distributions for Kent County Residents Distributions for Kent County Residents **This institution is an equal opportunity provider.** **This institution is an equal opportunity provider.** North End Community Ministry (NECM) 214 Spencer NE, Grand Rapids, MI 616-454-1097 Streams of Hope, 280 60th St SE, Kentwood, MI 616-272-3436 Distribution Times: Tuesday-Thursday 9 AM- 12:30 PM Distribution Times: Tuesday 6-8 PM; Thursday 11 AM- 1 PM & 6-8 PM The Green Apple, 4307 Kalamazoo Ave SE, Ste 25, Grand Rapids, MI 616-455-9411 North Kent Connect, 10075 Northland Dr. -

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents

HOME OFFICE SOLUTIONS Hettich Ideas Book Table of Contents Eight Elements of Home Office Design 11 Home Office Furniture Ideas 15 - 57 Drawer Systems & Hinges 58 - 59 Folding & Sliding Door Systems 60 - 61 Further Products 62 - 63 www.hettich.com 3 How will we work in the future? This is an exciting question what we are working on intensively. The fact is that not only megatrends, but also extraordinary events such as a pandemic are changing the world and influencing us in all areas of life. In the long term, the way we live, act and furnish ourselves will change. The megatrend Work Evolution is being felt much more intensively and quickly. www.hettich.com 5 Work Evolution Goodbye performance society. Artificial intelligence based on innovative machines will relieve us of a lot of work in the future and even do better than we do. But what do we do then? That’s a good question, because it puts us right in the middle of a fundamental change in the world of work. The creative economy is on the advance and with it the potential development of each individual. Instead of a meritocracy, the focus is shifting to an orientation towards the strengths and abilities of the individual. New fields of work require a new, flexible working environment and the work-life balance is becoming more important. www.hettich.com 7 Visualizing a Scenario Imagine, your office chair is your couch and your commute is the length of your hallway. Your snack drawer is your entire pantry. Do you think it’s a dream? No! Since work-from-home is very a reality these days due to the pandemic crisis 2020. -

Southern 7 Counties Food Pantry List Daystar Community Program • Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday 909 Washington Ave

Southern 7 Counties Food Pantry List Daystar Community Program • Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday 909 Washington Ave. 9:30 am – 1:00 pm Cairo, IL 62914 • Soup kitchen, mobile food pantry, (618) 734-0178 veteran’s program (Contact: Amy Conaway, Sherry Miller) • Outreach, rent assistance, help with Alexander [email protected] health care bills, food pantry County The Kitchen Table (Soup Kitchen) • Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday 1001 Washington Ave. 11:30 am – 1:00 pm Cairo, IL 62914 • Soup kitchen, mobile food pantry, (618) 734-0178 or (618) 734-9441 veteran’s program (Contact: Amy Conaway, Sherry Miller) [email protected] Shawnee Development Council Food • Wednesday 9:30 am – 11:30 am & 12:30 Pantry Hardin pm - 2:30 pm 147 N Main St. County Elizabethtown, IL 62931 (618) 287-7071 Goreville Ministerial Alliance • Tuesday & Thursday 9:00 am – 4:00 pm 114 S. Broadway St. • Serves Village of Goreville area Goreville, IL 62939 • Must fill out forms (618) 995-9360 Johnson Vienna First Baptist Food Pantry • 3rd Saturday of the month 9:00 am – County 301 N 7th St. 11:00 am Vienna, IL 62995 • Serves Johnson County (618) 658-3741 • Photo ID needed, proof of income & family size COPE Food Pantry • Monday, Wednesday, Friday 9:00 am – 1017 N Ave 3:00 pm Metropolis, IL 62960 • Must meet income guidelines for senior (618) 524-3635 box program (Contact: Bob Lingle) • Photo ID & proof of residency • Serves Massac County Lighthouse Assembly of God • 2nd and 4th Tuesday evenings 6:00 pm - 670 Airport Rd. 7:30 pm Massac Metropolis, IL 62960 • Must fill out form with current address, County (618) 524-2256 phone number, and number in household • Sign waiver Weaver Creek Food Pantry • 2nd Thursday of the month 9:00 am – 2997 N Ave. -

Library Pantries Feed Communities! by the CSLP Child & Community Well-Being Committee and Participating Libraries

Library Pantries Feed Communities! By the CSLP Child & Community Well-Being Committee and participating libraries Last month’s CSLP newsletter featured the story of the Public Pantry at the Woodstock Public Library in Illinois. We asked readers to submit a photo if they host a Little Free Pantry or have a pantry shelf in the library. Here are some creative and caring ways libraries are feeding their communities around the USA. Webster Library in Kingfield, Maine hosts a beautiful and well-used matching set: Little Free Pantry and Little Free Library. Photo: Morgain Bailey Laurel Public Library in Delaware added a community food distribution basket outside of the library this summer. Pataskala Public Library in Ohio set up its Little McCracken County Public Library in Paducah, Free Pantry this summer. Kentucky. Area Little Free Pantries have their own Facebook page: www.facebook.com/Paducahminifoodpantry Kincaid Community Library in Kansas has hosted a The Little Free Pantry at Johnston Public pantry since April 2019 for its small, rural town. Library in Iowa The Blessing Box in front of the Danbury Public Library in North Carolina Close-up of the Blessing Box at Danbury Public Pantry shelves at the George Culver Library, North Carolina Community Library in Sauk City, Wisconsin Left: Library manager Christina demonstrates proposed placement of a Little Free Pantry at Deale Library, part of the Anne Arundel County Public Library in Maryland. Right: the permanent LFP at Deale Library. LFPs are being placed at all Anne Arundel County Public Library locations in partnership with local anti-hunger organization Caring Cupboard. -

Community Soup Kitchens, Food Pantries

Newburgh Soup Kitchen (SK) and Food Pantry (FP) List NAME DAYS OPEN HOURS OF OPERATION ADDRESS CONTACT PHONE # E-MAIL ADDRESS Calvary Presbyterian Church (SK) 4th Saturday 5-7 p.m. 120 South Street J. Edward Lewis (845)562-8730 [email protected] 10-11 a.m. Ebenezer Baptist Church (FP) Tuesday 76 First Street Mary Burns (845)562-1168 [email protected] (2nd Tues.: meat) Ebenezer Baptist Church (SK) Wednesday 5:30-6:30 p.m. 76 First Street Sharon Minard (845)562-1168 [email protected] First United Methodist Church 4th Saturday 12-1 p.m.: Lunch 241 Liberty Street Audrey Allen (845)561-4365 [email protected] Grace United Methodist Church (FP) Thursday 10 a.m. – 12 p.m. – referral needed 265 Van Ness Street; Bev Tuthill (845)561-0176 [email protected] by the Salvation Army – ID needed Church: 468 Broadway for self and all members of household Grace United Methodist Church (SK) 2nd & 3rd Saturday 5-6 p.m.: Dinner 265 Van Ness Street Julie Baccaro (845)561-0176 [email protected] Grace United Methodist Church (SK) Every Saturday 7:30-9 a.m.: Breakfast Holy Deliverance (FP) Every other Wed. 2-4 p.m. 37 Chambers Street Judy Johnson (845)224-5011 [email protected] HVCC Food Cupboard (FB) – follows Mondays 1-2 p.m.; Dinners 100 Grand Street Sue Curry: FP (845)565-8526 [email protected] school calendar 2nd & 4th Fridays: 6 p.m. Bud Warren: Dinners Life Restoration (FP) Mondays 11 a.m. – 12 p.m. 136 First Street (845)561-8741 New City Church of Good Shepherd (FP) Tuesdays 12:30 – 2 p.m. -

Why Buy New? 2806 W 58Th St N Plan: Bella #2 Price: $359,969 (Includes $18,000 Lot) Finished Sqft: 3,095 (1,555 Main, 1450 Lower) Bedrooms: 4 Bathrooms: 3

Model Homes RJ Castle Custom Homes Why Buy New? 2806 W 58th St N Plan: Bella #2 Price: $359,969 (Includes $18,000 lot) Finished Sqft: 3,095 (1,555 main, 1450 lower) Bedrooms: 4 Bathrooms: 3 Open split bedroom floor plan with finished basement. Custom mantle/tile gas fireplace in living room. Large kitchen/dining with granite counter- tops and walk in pantry. Accent walls in master suite, gorgeous custom shower and large walk-in closet. Drop zone storage and laundry off of garage. View-out out basement with large family room and wet bar. Large front patio and back covered deck. Buckert Contracting 2802 W 58th St N Price: $338,433 (Includes $16,000 lot) Finished sqft: 2,317 (1555 main, 762 lower) Bedroom: 3 Bath: 2 Lower Level Garage: 3 Main Level Open split bedroom floor plan w/ partial basement finish. Fireplace, built-in bookcases, LED can lighting and beamed ceiling in living room. Master suite with walk-in tile shower and large walk-in closet. Drop zone storage off garage. Kitchen w/ granite island, walk-in pantry and under cabinet lighting. Wood floors in kitchen, dining, and living room. Granite on all countertops. View-out basement finish includes a rec room with custom built ins, wet bar and bathroom. Two additional bedroom that could be finished or used for storage. SM Design LLC Main Level Lower Level 2854 W 58th St N Plan : The Braxton Price: $358,600 (Includes S23,000 lot) Finished Sqft: 1,770 Sqft Bedroom: 3 Bath: 2-1/2 Garage: 3 New open split bedroom floor plan. -

Do You Need Food? When, Where & How to Connect with Food Assistance in Your County

Do you need food? When, where & how to connect with food assistance in your county. To qualify for these services your gross monthly income must be equal to or less than these amounts based on household size: Available Programs Household Household Household Household Household Household Additional Size—1 Size—2 Size—3 Size—4 Size—5 Size—6 Member +1 Food Assistance / Food Stamps Call MOF Outreach 614-782-5503 Senior Food Box / CSFP Program Call Center for Seniors 740-686-9832 Add $468 $1,316 $1,784 $2,252 $2,720 $3,188 $3,656 for each additional School Free Lunch Program Apply at www.schoollunchapp.com household member Women, Infants, & Children Program Call WIC 740-676-2232 $1,872 $2,538 $3,204 $3,870 $4,536 $5,202 Add $666 School Reduced Price Lunch Program for each additional Apply at www.schoollunchapp.com household member Food Pantry Appointment Call 211 or 1-216-436-2100 $2,024 $2,744 $3,464 $4,184 $4,904 $5,624 Add $720 Free Community Produce Markets for each additional midohiofoodbank.org/gethelp/getfood household member Call the MOF Benefits Assistance Outreach team with questions about any of these programs 614-448-6889. “This institution is an equal opportunity provider, and employer.” All data and times are subject to change. Rev12/2018 AMT Fayette Hunger Resources Pantry Name Days / Hours or Distribution Service Area Zip Code Fayette County Food Pantry Mon, Wed, Fri: 1pm-3pm Fayette County 214 North Hinde Street Washington Court 43160 740-335-2067 Heritage Memorial Church Pantry Monday: 10am-11am Fayette County 412 Rose Ave 2nd: 10am-2pm Washington Court House 43160 740-335-1079 Gregg Street Worship Center Pantry 3rd Monday: 4pm-6pm Washington Court House 424 Gregg Street Bloomingburg Washington Court House 43160 740-335-8625 Bread of Life Saturday: 9am-12pm Fayette County 721 S. -

Starting Your Own Food Pantry

STARTING YOUR OWN FOOD PANTRY Revised January 2015 SECOND HARVEST INTRODUCTION Second Harvest Food Bank of Middle Tennessee's mission is to feed hungry people and work to solve hunger issues in our community. Second Harvest opened its doors in 1978 with commitment from several community leaders. The purpose of the organization was to provide a central distribution center for companies, groups and individuals who wished to help provide food for hungry people in Middle Tennessee. Modeled after the first food bank established in Phoenix in the mid-1970s, Second Harvest was designed to collect food that would otherwise be wasted, inspect and sort this food and distribute it to soup kitchens, pantries and shelters serving the hungry. During the first year, this process resulted in a total distribution of 160,000 pounds of food to 75 Partner Agencies. Today, Second Harvest distributes tens of millions of pounds each year and counts soup kitchens, food pantries, senior centers, drug & alcohol treatment centers, youth programs and homeless shelters among its Partner Agencies receiving food and working to end hunger. Second Harvest is one of the largest and most comprehensive of over 200 food banks in the Feeding America network. We partner with more than 450 Partner Agencies throughout our 46-county service area in Middle and West Tennessee to feed the hungry. Second Harvest Food Bank of Middle Tennessee 331 Great Circle Road Nashville, TN 37228 Phone: 615-329-3491 Fax: 615-329-3988 secondharvestmidtn.org Starting Food Pantry/Jan. 2015 2 WHAT IS A FOOD PANTRY? A food pantry is a community-based program that collects and safely stores food and household products for free distribution to low-income and needy members of the community. -

Bethlehem Food Pantry Make a Food Donation Organize a Food Drive/Collection a Joint Program of Make Financial Contributions Bethlehem Senior Projects, Inc

How Can You Help? Bethlehem Food Pantry Make a food donation Organize a food drive/collection A joint program of Make financial contributions Bethlehem Senior Projects, Inc. Where Can Food Be Donated? and the Town of Bethlehem There are donation boxes at: Senior Services Bethlehem YMCA Delmar Marketplace You can schedule a delivery direct- ly to the Bethlehem Town Hall What can be donated to the Bethlehem Food Pantry? Please call first to check on what pantry items are needs. Food items with dates that are not expired Gift cards to local grocery stores and pharmacies Monetary donations are accepted via mail or visiting the Bethlehem Senior Projects, Inc. website at Bethlehem Senior Projects, Inc. and clicking the “Donate Now” button. Please designate Bethle- Bethlehem Town Hall hem Food Pantry on the memo line 445 Delaware Avenue on your check and mail to: Delmar, New York Bethlehem Senior Projects, Inc. 518-439-4955, x 1176 c/o Food Pantry 445 Delaware Ave, Delmar, NY 12054 Senior/Food Pantry Folder/Food Pantry 10 -19 The Bethlehem Food Pantry Who Can Use the Food Pantry? How To Use the Food Pantry? The Bethlehem Food Pantry has non Residents of the Town of Bethlehem The Bethlehem Food Pantry is open -perishable foods, as well as refrigerat- who are in need of food can use the during specific hours. Therefore, it is ed and frozen items. Personal care Bethlehem Food Pantry once every thir- helpful to call and schedule an appoint- products and toiletries are often availa- ty (30) days and on an emergency basis.