Learning from North Carolina Exploring the News and Information Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TH F^ REGISTER

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 3-8-1977 The Register, 1977-03-08 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1977-03-08" (1977). NCAT Student Newspapers. 681. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/681 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THf^ REGISTER "COMPLETE AWARENESS FOR COMPLETE COMMITMENT" VOLUME XLVIII NUMBER 44 NORTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL AND TECHNICAL STATE UNIVERSITY, GREENSBORO MARCH 8, 1977 A&T Library Director Welcomes Investigation may prove that some of the staff By Benjamin T. Forbes are being paid for hours they are "I would welcome an not working. When asked if she investigation. I think an could supply names as to who investigation into the library some of the staffers were, Ms. would prove to be interesting," said Ms. Tommie Young, director Young said she would not go of F.D. Bluford Library. into personal cases. Ms. Young's comments were There had been and still is a in response to some accusations growing concern about the made by some library employees number of staff resignations. Ms. who have since resigned. Several Young said that those persons of those accusations appearered who resigned probably had in recent issues of The A&T better job opportunities. -

LOCAL NEWS IS a PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21St Century

LOCAL NEWS IS A PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21st Century INTRODUCTION A free and independent press was so fundamental to the founding vision of “Congress shall make no law democratic engagement and government accountability in the United States that it is called out in the First Amendment to the Constitution alongside individual respecting an establishment of freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly. Yet today, local newsrooms and religion, or prohibiting the free their ability to fulfill that lofty responsibility have never been more imperiled. At exercise thereof; or abridging the very moment when most Americans feel overwhelmed and polarized by a the freedom of speech, or of the barrage of national news, sensationalism, and social media, Colorado’s local news outlets – which are still overwhelmingly trusted and respected by local residents – press; or the right of the people are losing the battle for the public’s attention, time, and discretionary dollars.1 peaceably to assemble, and to What do Colorado communities lose when independent local newsrooms shutter, petition the Government for a cut staff, merge, or sell to national chains or investors? Why should concerned redress of grievances.” citizens and residents, as well as state and local officials, care about what’s happening in Colorado’s local journalism industry? What new models might First Amendment, U.S. Constitution transform and sustain the most vital functions of a free and independent Fourth Estate: to inform, equip, and engage communities in making democratic decisions? 1 81% of Denver-area adults say the local news media do very well to fairly well at keeping them informed of the important news stories of the day, 74% say local media report the news accurately, and 65% say local media cover stories thoroughly and provide news they use daily. -

Der Spiegel-Confirmation from the East by Brian Crozier 1993

"Der Spiegel: Confirmation from the East" Counter Culture Contribution by Brian Crozier I WELCOME Sir James Goldsmith's offer of hospitality in the pages of COUNTER CULTURE to bring fresh news on a struggle in which we were both involved. On the attacking side was Herr Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the German news magazine, Der Spiegel; on the defending side was Jimmy. My own involvement was twofold: I provided him with the explosive information that drew fire from Augstein, and I co-ordinated a truly massive international research campaign that caused Augstein, nearly four years later, to call off his libel suit against Jimmy.1 History moves fast these days. The collapse of communism in the ex-Soviet Union and eastern Europe has loosened tongues and opened archives. The struggle I mentioned took place between January 1981 and October 1984. The past two years have brought revelations and confessions that further vindicate the line we took a decade ago. What did Jimmy Goldsmith say, in 1981, that roused Augstein to take legal action? The Media Committee of the House of Commons had invited Sir James to deliver an address on 'Subversion in the Media'. Having read a reference to the 'Spiegel affair' of 1962 in an interview with the late Franz Josef Strauss in his own news magazine of that period, NOW!, he wanted to know more. I was the interviewer. Today's readers, even in Germany, may not automatically react to the sight or sound of the' Spiegel affair', but in its day, this was a major political scandal, which seriously damaged the political career of Franz Josef Strauss, the then West German Defence Minister. -

Venues and Highlights

VENUES AND HIGHLIGHTS 1 EDENTON STREET 8 FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH - Memorial Hall INTERSECTION OF FAYETTEVILLE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH BeBop Blues & All That Jazz | 7:00PM - 11:00PM & DAVIE ST. Triangle Youth Jazz Ensemble | 7:00PM, 9:00PM 2 3 4 Bradley Burgess, Organist | 7:00, 9:00PM Early Countdown & Fireworks with: 1 Sponsored by: Captive Aire Steve Anderson Jazz Quartet | 8:00PM Media Sponsor: Triangle Tribune Open Community Jam | 10:00PM Barefoot Movement | 6:00-7:00PM Sponsored by: First Citizens Bank 5 Early Countdown | 7:00PM NORTH CAROLINA MUSEUM OF Media Sponsor: 72.9 The Voice 6 2 NATURAL SCIENCES Fireworks | 7:00PM Children’s Celebration | 2:00-6:00PM 9 MORGAN ST. - GOLD LEAF SLEIGH RIDES Gold Leaf Sleigh Rides | 8:00 -11:00PM Celebrate New Year’s Eve with activities including henna, Boom Unit Brass Band | 7:30-8:30PM Sponsored by: Capital Associates resolution frames, stained glass art, celebration bells, a Media Sponsor: Spectacular Magazine Caleb Johnson 7 toddler play area, and more. Media Sponsor: GoRaleigh - City of Raleigh Transit & The Ramblin’ Saints | 9:00-10:00PM 10 TRANSPORTATION / HIGHWAY BUILDING 10 Illiterate Light | 10:30PM-12:00AM BICENTENNIAL PLAZA Comedy Worx Improv | 7:30, 8:45, 10:15PM 3 Sponsored by: Capital Investment Companies 9 Children’s Celebration | 2:00-6:00PM Media Sponsor: City Insight Countdown to Midnight | 12:00AM Celebrate New Year’s Eve with interactive activities 11 including the First Night Resolution Oak, a New Year’s Fireworks at Midnight | 12:00AM FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH WILMINGTON ST. 8 castle construction project, a Midnight Mural, and more. -

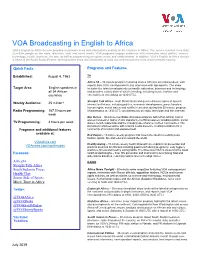

VOA E2A Fact Sheet

VOA Broadcasting in English to Africa VOA’s English to Africa Service provides multimedia news and information covering all 54 countries in Africa. The service reaches more than 25 million people on the radio, television, web, and social media. VOA programs engage audiences with information about politics, science, technology, health, business, the arts, as well as programming on sports, music and entertainment. In addition, VOA’s English to Africa service is home to the South Sudan Project, which provides news and information to radio and web consumers in the world’s newest country. Quick Facts Programs and Features Established: August 4, 1963 TV Africa 54 – 30-minute program featuring stories Africans are talking about, with reports from VOA correspondents and interviews with top experts. The show Target Area: English speakers in includes the latest developments on health, education, business and technology, all 54 African and provides a daily dose of what’s trending, including music, fashion and countries entertainment (weekdays at 1630 UTC). Straight Talk Africa - Host Shaka Ssali and guests discuss topics of special Weekly Audience: 25 million+ interest to Africans, including politics, economic development, press freedom, human rights, social issues and conflict resolution during this 60-minute program. Radio Programming: 167.5 hours per (Wednesdays at 1830 UTC simultaneously on radio, television and the Internet). week Our Voices – 30-minute roundtable discussion program with a Pan-African cast of women focused on topics of vital importance to African women including politics, social TV Programming: 4 hours per week issues, health, leadership and the changing role of women in their communities. -

J Ohn S. and J Ames L. K Night F Oundation

A NNUAL REPORT 1999 T HE FIRST FIFTY YEARS J OHN S. AND JAMES L. KNIGHT FOUNDATION he John S. and James L. Kn i ght Fo u n d a ti on was estab- TA B L E O F CO N T E N T S l i s h ed in 1950 as a priva te fo u n d a ti on indepen d en t Tof the Kn i g ht bro t h ers’ n e ws p a per en terpri s e s . It is C h a i r m a n’s Letter 2 ded i c a ted to f urt h ering their ideals of s ervi ce to com mu n i ty, to the highest standards of j o u r n a l i s t ic excell en ce and to the Pr e s i d e n t ’s Message 4 defense of a free pre s s . In both their publishing and ph i l a n t h ropic undert a k i n g s , History 5 the Kn i ght bro t h ers shared a broad vi s i on and uncom m on devo ti on to the com m on wel f a re . It is those ide a l s , as well as Philanthropy Takes Root 6 t h eir ph i l a n t h ropic intere s t s , to wh i ch the Fo u n d a ti on rem a i n s The First Fifty Years 8 f a i t h f u l . -

Media Coverage of Ceos: Who? What? Where? When? Why?

Media Coverage of CEOs: Who? What? Where? When? Why? James T. Hamilton Sanford Institute of Public Policy Duke University [email protected] Richard Zeckhauser Kennedy School of Government Harvard University [email protected] Draft prepared for March 5-6, 2004 Workshop on the Media and Economic Performance, Stanford Institute for International Studies, Center on Development, Democracy, and the Rule of Law. We thank Stephanie Houghton and Pavel Zhelyazkov for expert research assistance. Media Coverage of CEOs: Who? What? Where? When? Why? Abstract: Media coverage of CEOs varies predictably across time and outlets depending on the audience demands served by reporters, incentives pursued by CEOs, and changes in real economic indicators. Coverage of firms and CEOs in the New York Times is countercyclical, with declines in real GDP generating increases in the average number of articles per firm and CEO. CEO credit claiming follows a cyclical pattern, with the number of press releases mentioning CEOs and profits, earnings, or sales increasing as monthly business indicators increase. CEOs also generate more press releases with soft news stories as the economy and stock market grow. Major papers, because of their focus on entertainment, offer a higher percentage of CEO stories focused on soft news or negative news compared to CEO articles in business and finance outlets. Coverage of CEOs is highly concentrated, with 20% of chief executives generating 80% of coverage. Firms headed by celebrity CEOs do not earn higher average shareholder returns in the short or long run. For some CEOs media coverage equates to on-the-job consumption of fame. -

Happy Birthday Rotary Public Image

A note from Governor Ineke. Happy Birthday Rotary Bob and I are excited about this month’s birthday celebration for Rotary. We are the best story “never told”, but that’s about to change. On Friday February 19 the Charlotte Business Journal will have a full page dedicated to Rotary. On Saturday February 20 we are having our Global Swimarathon to “End Polio Now”. On Sunday February 21 the Charlotte Observer will deliver 150,000 newspapers with a 20 page Rotary insert. We are incrediblly proud of the 15 Rotary Clubs that stepped up to have a page dedicated to all their work in Rotary. On Monday February 22 the Duke Energy building in downtown Charlotte will be lit with our own colors…blue and gold. Special thanks to Laura Collinge, our District PR Chair, for making this happen. Give the gift of Rotary. Consider making a birthday gift to Rotary to mark the organization’s 111th year, on 23 February. When you give to Rotary, you empower your fellow leaders to improve their communities and make a lasting impact. Public Image: A Great Opportunity for our Clubs to tell their story! Save your Rotary insert from the Charlotte Observer and display it in your office, your waiting room, etc. and share the Rotary story. Thanks to the following clubs for participating: Ballantyne, Cabarrus County, Charlotte, Charlotte Dilworth, Charlotte End of the Week, Charlotte North, Charlotte Providence, Charlotte South, Charlotte Southpark, Concord, Gastonia, Monroe, Union West. Also featured featured are Trees Charlotte, Rotary Butterfly Gardens, Kilimanjaro, Youth Exchange, SFTL, District Map and all our 59 clubs. -

Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers Dana Armstrong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Dana, "Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1711. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1711 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies from William & Mary by Dana Ellise Armstrong Accepted for ______Honors_________ (Honors) _________________________________________ Elizabeth Losh, Director Brian Castleberry _________________________________________ Brian Castleberry Jon Pineda _________________________________________ Jon Pineda Candice Benjes-Small _____________________________ Candice Benjes-Small ______________________________________ Stephanie Hanes-Wilson Williamsburg, VA May 14, 2021 Acknowledgements There is nothing quite like finding the continued motivation to work on a thesis during a pandemic. I would like to extend a huge thank you to all of the people who provided me moral support and guidance along the way. To my thesis and major advisor, Professor Losh, thank you for your edits and cheerleading to get me through the writing process and my self-designed journalism major. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

Nuvo.Net / Single in the Circle City

nuvo.net / Single in the Circle City [ Indy's weekly alternative newspaper highlighting arts, entertainment and social justice ] SEARCH NUVO.NET: www.nuvo.net/ personals/ community Classifieds Contests Coupons NEW! Posted on February 09, 2005 / Email to a friend / Comments (closed) Forums Printer-friendly version irishchick NUVO Blogs NEWS I'm currently a Personals: Café Love receptionist at a NUVO Radio Single in the Circle City veterinary clinic, but Readers Poll am looking into Multimedia going back to... By Molly G. Martin e-Subscriptions Browse... Women Seeking I awoke one stormy night certain I was in hell. Lights were flashing, Hall & Oates was Men blaring and a teeny-tiny hellhound was gnawing on my toes. Turns out it was just a Women seeking power surge that happened to bring my radio to life and scare my miniature dachshund Women to death. in every issue Men seeking Women Arts You can imagine the flashback as months later I found myself swaying awkwardly to Men seeking Men Baggage Claim “Through the Years,” thrown slightly off-balance by mood lighting and too much www.nuvo.net/ Our Writers watery Merlot, not to mention the toddler knee-capping me in time to the music. personals/ Cuisine Cover Story But this was no nightmare: this was my beloved college roommate’s wedding. And I Hammer's Column was wearing periwinkle crepe. Hoppe's Column Humor/Satire Since June 2003, I’ve been to seven weddings. Most were lovely, elegant affairs Letters celebrating people I love (or, failing that, excellent opportunities to drink hard liquor Movies at 3 in the afternoon without the dirty looks).