Analysis and Action for Sustainable Development of Hyderabad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hyderabad Front Copy

A B C Balaji D Today, Deccani, Urdu and Hyderabad is one of the few Rajiv Gandhi Nizampet Telugu mix to form a tongue On the map Colony cities in India where heritage Miyapur Ahwal RS CGHS Damamaiguda and development go hand in that is uniquely Hyderabadi. Hospital Say Aadab to Swaroopa Hospital Laxminarayan Sainikpuri hand harmoniously, Today, it is With teahouses serving sweet Hospital Ameerpet B2 Miyapur Yellareddyguda milky chai and bakeries S E CUNDER A B A D Cavalry Barracks RS HYDERABAD! the joint capital of two states, Banjara Hills B2 Kukatpally selling Karachi biscuits, the Hafeezpet d Andhra Pradesh and the Sandhya IDPL High a 1 Begumpet C1 o Ammuguda RS Nagavaram School R city is a delicious mix of Forum Mall Hospital newly formed Telangana. G Charminar C2 M Hindu and Muslim cultures. Kukatpally Trimulgherry The old city is full of tiny Hafeezpet RS Indian Drugs & Falaknuma Palace B3 Ramkrishnapuram RS Pharmaceutical Ltd. Military Cherapally winding lanes, traditional HITEC City Hospital Gachibowli A2 Moosapet Central Jail curio stores, noisy auto Hyderabad also used to be MMTS Station twinned with Secunderabad, Golkonda Fort A2 AOC RS rickshaws; and myriad Balaji HITEC CITY an erstwhile British cantonment. Habsiguda C2 Sanath Nagar RS Colony Sadiguda RS Moula languages and crowds. The Westin Don Bosco Hyderabad University of Ali HCL Separated by the Hussain Hardware Park B3 Degree College Old Airport Vikrampuri Hyderabad is also called the Hyderabad Trident Colony HICC Complex ESI Begumpet Sagar Lake, Secunderabad is Himayat Sagar A3 JBS Malkajgiri RS City of Pearls given its Shilparamam Paradise Novotel Nature Care now considered a part of HITEC City A1 Shilparamam Parade Grounds history as a Pearls, and HITEC City Green Park Lalaguda RS Yusufguda Deccan Secunderabad RS Ram Talkies Hyderabad, despite its Hussain Sagar C2 Flying Spaghetti Ameerpet Continental diamond trading centre. -

List of Colleges in Ranga Reddy District

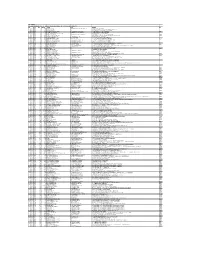

LIST OF COLLEGES IN RANGA REDDY DISTRICT YEAR OF COLLEGE S NO COLLEGE NAME & ADDRESS STARTING FIRST YEAR STRENGTH DURING THE ACADEMIC YEARS CODE 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 15 RANGA REDDY I Government 1 15003 GOVT JR COLLEGE NAWABPET 2001-2002 68 112 136 137 2 15038 GOVT. JUNIOR COLLEGE, VIKARABAD 2013-2014 3 15043 GOVT JR COLLEGE TANDUR 1985-1986 698 659 703 675 4 15044 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE PEDDAMUL 1999-2000 178 190 176 152 5 15056 GOVT JR COLLEGE MEDCHAL 1976-1977 163 150 113 140 6 15071 GOVT JR COLLEGE CHEVELLA 1981-1982 78 102 135 140 7 15084 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE PARGI 1981-1982 136 152 151 121 8 15100 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE MARPALLI 1981-1982 201 242 227 276 9 15111 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE SHAMSHABAD 1982-1983 90 76 63 107 10 15117 GOVT JR COLLEGE, MAHESWARAM 2009-2010 91 54 55 97 11 15123 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE, RAJENDRANAGAR 1981-1982 130 119 96 128 12 15168 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE, BOLLARAM 1980-1981 237 225 148 157 13 15196 GOVT JR COLLEGE, QUTUBULLAPUR 2009-2010 68 77 45 42 14 15206 NEW GOVT JR COLLEGE, KUKATPALLI 1981-1982 425 369 334 283 15 15262 GOVT JR COLLEGE, RAMACHANDRAPURAM 1985-1986 222 300 239 268 16 15277 NEW GOVT.JR.COLLEGE,RAYADURGAM,R R DIST 2011-2012 0 0 73 107 17 15297 GOVT JUNIOR COLLEGE YACHARAM 2000-2001 166 314 208 190 18 15301 GOVT JR COLLEGE, KANDUKUR 2009-2010 55 62 49 75 19 15310 GOVT JR COLLEGE MOMINPET 1999-2000 94 124 126 87 LIST OF COLLEGES IN RANGA REDDY DISTRICT YEAR OF COLLEGE S NO COLLEGE NAME & ADDRESS STARTING FIRST YEAR STRENGTH DURING THE ACADEMIC YEARS CODE 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 20 15322 GOVT JR COLLEGE DOMA 2001-2002 215 268 250 189 Tribal Welfare 21 15324 APTWRS (BOYS) JR COLLEGE, KULKACHARLA 2007-2008 35 62 60 50 Social Welfare 22 15039 A.P.S.W.R. -

Sr. No. Branch ID Branch Name City Branch Address Branch Timing Weekly Off Micrcode Ifsccode

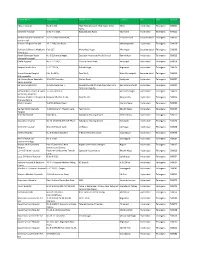

Sr. No. Branch ID Branch Name City Branch Address Branch Timing Weekly Off MICRCode IFSCCode Adilabad, Andhra Pradesh,H.No. 4-3-60/10, 11,Opp. Bus Stand, N H No. 7,Adilabad 1 727 Adilabad Adilabad 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 504211002 UTIB0000727 504001, Andhra Pradesh H No: 1-1-3/4. Ground Floor, Mahalakshmi Temple Road, Armoor, Dist.Nizamabad, 2 2602 Armoor Armur 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 503211203 UTIB0002602 Telangana, Pin 503224 3 3966 Bachupally Bachupally Satyam towers, G-6, D.No : 3-3/16/G6 Bachupally (Mandal), Hyderabad - 500090 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 500211081 UTIB0003966 Ground floor & first Floor : House No: 10-1-65 Krishna Mandir Road, Bellampalli - 4 3965 Bellampally Bellampalli 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 504211099 UTIB0003965 504251 5 3574 Bhongir Bhongir No:1-5-330, Station road, opp : sai baba temple Bhongir – 508116 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 508211116 UTIB0003574 Vijay Manohar Mansion, Door No. 5-105/6/1, Ground Floor, Plot No.14 &15, Survey 6 1114 Bibinagar Bibinagar No.596, Hyderabad-Warangal Main Road, Bibinagar Village & Mandal, Dist. Nalgonda, 9:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. 2nd & 4th Saturday and Sunday 500211025 UTIB0001114 Andhra Pradesh 508126 No.1-19/13, Veerabhadra Complex, Opp. Market Yard, Hyderabad Main Road, Chevella, 7 1266 Chevella Chevella 9:30 a.m. -

5R Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

5R bus time schedule & line map 5R Kowkoor to Mehdipatnam View In Website Mode The 5R bus line (Kowkoor to Mehdipatnam) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kowkoor: 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM (2) Mehdipatnam Bus Stop: 6:39 AM - 4:29 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 5R bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 5R bus arriving. Direction: Kowkoor 5R bus Time Schedule 37 stops Kowkoor Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM Monday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM Mehdipatnam Tuesday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM Sarojini Devi Eye Hospital Wednesday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM NMDC Bus Stop Thursday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM Ac Guards Friday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM Lakdikapul Saturday 2:35 PM - 10:30 PM Telephone Bhavan Secretariat 5R bus Info Secretariat Road, Hyderābād Direction: Kowkoor Dbr Mills Stops: 37 Trip Duration: 46 min Tank Bund Line Summary: Mehdipatnam, Sarojini Devi Eye Hospital, NMDC Bus Stop, Ac Guards, Lakdikapul, NH44, Hyderābād Telephone Bhavan, Secretariat, Dbr Mills, Tank Bund, Boats Club (Rp Road), Boats Club Bus Stop, Bible Boats Club (Rp Road) House, Bata, Patny Center, Patny, Jubilee Bus Station, Hps High School, Vikrampuri Bus Stop, Boats Club Bus Stop Karkhana, Karkhana Temple Arch, Hanuman Temple NH44, Hyderābād (Tirumalgherry), Hanuman Temple Bus Stop, Tirumalgherry Bus Stop, Lal Bazar Bus Stop, Eme Bible House Bus Stop, Family Quarter Bus Stop, Maruti Nagar, Lothkunta Bus Stop, Ram Nagar – Alwal, Alwal Bus Bata Station, Raithu Bazar, Lakadawala Bus Stop, Bollaram Bazar Railway Station, Sadhana -

S.No. Shop Address 1. Vikrampuri H.NO.D-18,VIKRAMPURI,SECUNDERABAD-500009. 2. Srinagar Colony P.NO: 144,AKASH GANGA COMPLEX, SRINAGAR COLONY,HYDERABAD-500073

S.no. Shop Address 1. Vikrampuri H.NO.D-18,VIKRAMPURI,SECUNDERABAD-500009. 2. Srinagar Colony P.NO: 144,AKASH GANGA COMPLEX, SRINAGAR COLONY,HYDERABAD-500073. 3. Hi-Tech City SY NO: 64,PLOT NO: 20, SECTOR NO: 1, HUDA TECHNO ENCLAVE, MADHAPUR, HYDERABAD-500081. 4. Secunderabad SECUNDERABAD CLUB, PICKET, SECUNDERABAD - 500009. Club 5. Somajiguda 6-3-902/A, CENTRAL PLAZA, RAJBHAVAN ROAD,SOMAJIGUDA,HYDERABAD - 500082. 6. Himayathnagar 3-6-263/264,CCPL-STERLING,HIMAYATHNAGAR,HYDERABAD-500029. 7. Banjara Hills -12 8-2-680/3,ROAD NO: 12,BANJARA HILLS,HYDERABAD-500034. 8. East Marredpally PLOT NO:25/B/B,MCH NO: 10-3-150,151/B,PLOT NO:25/B/E,MCH NO:10-3-150,151/E & PLOTNO:25/B/D,MCHNO:10-3-150,151/D,ST.JOHNS ROAD,EAST MAREDPALLY,SECUNDERABAD-500026. 9. Yousufguda 8-3-224/4/A/11&12, YOUSUFGUDA MAIN ROAD, MADHURA NAGAR,HYDERABAD- 500045. 10. A.S. Rao Nagar H:NO:1-19-71/A-8/1,PLOT NO A-8, SURVEY NO 500, RUKMINIPURI COLONY,AISHWARYA CHAMBERS,GROUND FLOOR,A S RAO NAGAR, KAPRA MUNICIPALITY, HYDERABAD-500062,R R DST. 11. Kondapur -1 SURVEY 37, EKTHA PEARL,OPP.BOTANICAL GARDENS,WHITE FIELDS,KONDAPUR,KOTHAGUDA VILLAGE,R R DST,HYDERABAD-500084. 12. Ameerpet SHOP NO:2,GROUND FLOOR,ANAND CAPITAL COMPLEX,MUNICIPAL NOS.7-1-79,7-1- 79/5,7-1-79/6,7-1-79/7,7-1-80,SURVEY NO:77, AMEERPET,HYDERABAD-500016. 13. Banjara Hills -7 H:NO:8-2-542/A, SUNIL CHAMBERS,BANJARA HILLS,ROAD NO:7,HYDERABAD-500034. -

GURU NANAK INSTITUTE of TECHNOLOGY City Office: B2, 2Nd Flr, Above Bata, Vikrampuri Colony, Karkhana Road, Secunderabad-50009, Telangana, India

GURU NANAK INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY City Office: B2, 2nd Flr, Above Bata, Vikrampuri Colony, Karkhana Road, Secunderabad-50009, Telangana, India. Ph: +91-40-6632 3294, 6517 6117, Fax: +91-40-2789 2633 www.gnithyd.ac.in Campus: Ibrahimpatnam, R.R. District, Hyderabad-501506, Telangana, India. Ph: (0/95) 8414-20 21 20/21 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Date: 19-10-2014 Site visit To Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation The Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) is the civic body that oversees Hyderabad, the capital and largest city in the Indian state of Telangana. It is the local government for the cities of Hyderabad and Secunderabad. Its geographical area covers most of the urban development agency the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA). 64 ex-officio members including 5 Lok Sabha MPs whose constituencies are in GHMC jurisdiction vote in GHMC election. Formation of Hyderabad Municipal Board and Chaderghat Municipal Board In the year 1869, Municipal administration was first introduced for the city of Hyderabad. The city of Hyderabad was divided into four and the suburbs of Chaderghat were divided into five divisions. The whole management of both the city and the suburbs was handled by the then City Police Commissioner, Kotwal-e-Baldia. In the same year, Sir Salar Jung-1, the then Prime Minister of Hyderabad State under the Nizam, has constituted the Department of Municipal and Road Maintenance. He also appointed a Municipal Commissioner for Hyderabad Board and Chaderghat Board. At that time, city was just 55 km2 with a population of 3.5 lakhs. In 1886, the suburban area of Chaderghat was handed over to a separate officer and then Chaderghat became Chaderghat Municipality. -

Dpid Folio Wno Net Div Name Fname Address Pin Physical

HIL LIMITED INTERIM DIVIDEND 2015-16 - UNPAID SHAREHOLDERS LIST AS ON 4TH MARCH 2016 DPID FOLIO WNO NET_DIV NAME FNAME ADDRESS PIN PHYSICAL 000002 68 6000.00 ANWARI BEGUM W/O NAWAB AKBARYARJUNG BAHADUR TROOP BAZAR,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000003 92 60.00 AMINA KHATOON N A 5-9-1101 OPP MUNICIPAL PARK,,GUNFOUNDRY,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000007 142 120.00 AZIZULLA SHARIEF N A F-4-837 NEAR RED HILLS MOSQUE,,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000010 171 240.00 NAWAB M. ABUL FATEH KHAN S/O. NAWAB SULTAN-UL-MULK FATEHBAGH,SANATHNAGAR,,HYDERABAD 500018 PHYSICAL 000011 184 120.00 AMEERALI RAHIMTULLA S/O ABDULLA HAJI RAHIMTULLA 66 ALEXANDRA ROAD,,,,SECUNDERABAD. PHYSICAL 000019 255 60.00 SAHEBZADI BASHEERUNNISA BEGUM N A AIWAN,,BEGUMPET,,,SECUNDERABAD. PHYSICAL 000024 284 720.00 DINA N. LAKDAWALLA D/O KAOSHUSWANJI D LAKDAWALA GOOL MANZIL,,72 SAPPERS LINES,,SECUNDERABAD 500003 PHYSICAL 000031 333 1800.00 FRAMROZ OOKERJI DINSHAW N A 5-8-47,FATHESULTAN LANE,,STATION ROAD,NAMPALLY,HYDERABAD 500001 PHYSICAL 000049 413 900.00 MOHAMED SULTANUDDIN S/O MOHAMED SULTAN 4-1-1/23,KING KOTHI,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000051 424 240.00 M.E. NISAR AHMED S/O ALI MOHAMED 11-4-911 CHILAKALAGUDA,,,,SECUNDERABAD PHYSICAL 000053 434 360.00 MOHAMED ABDUL RASHEED N A 12-1-1048 NORTH LALLAGUDA,,,,SECUNDERABAD 500017 PHYSICAL 000054 436 180.00 MOHAMED ABDUL KAREEM S/O HAJI MOHD IBRAHIM KHAN E-12-584 SYEDALIGUDA,,KARWAN SAHOO,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000055 443 660.00 MOHAMED ZEENATH HUSSAIN S/O MOHAMMED YOUSUF 20-4-717 MOHELLA SHAH GUNJ,,,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000057 450 120.00 MOHAMED FARIDUDDIN S/O MOHAMED QURBAN ALI MANJLAGUDA VILLAGE,,MADUR B.P.O.,,NARSAPUR TQ PHYSICAL 000058 456 150.00 MOHAMED KHAJA MIAN S/O SHAIK MASTAN 1166 BAZARGHAT,,NEAR KUTUB SHAHI MASZID,,NAMPALLY,,HYDERABAD PHYSICAL 000059 462 150.00 MOHAMED YOUSUF S/O KHATTAL AHMED 12-1-922/58,OLD FEELKHANA, ASIFNAGAR,,HYDERABAD 500028 PHYSICAL 000062 477 120.00 MIRZA RAZAK ALI BAIG S/O MIRZA MAHBOOB BAIG C/O. -

RHICL Network Hospital List.Xlsx

Hospital Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Location City State Pincode Aditya Hospital No.4-1-160, Tilak Road,Opposite Tilak Nagar Water Abids Hyderabad Telangana 500001 Tanks, Kamineni Hospital D.No.4-1-1227, Boggulakunta Road, King Kothi Hyderabad Telangana 500001 Krishna Institute Of Medical 1-8-31/1 Ministers Road, Secunderabad Secunderabad Telangana 500003 Sciences Ltd Premier Hospitals Pvt Ltd 12-2-718,Cross Road, Mahedipatnam Hyderabad Telangana 500028 Rainbow Children's Medicare Plot C17, Manovikas Nagar, Vikrampuri Secunderabad Telangana 500009 Private Ltd. Advalli Damodar Reddy No.9-2,Sharada Nagar, Opposite Hyderabad Public School, Ramanthpur Hyderabad Telangana 500013 Memorial Hospital Challa Hospital No.7-1-71/A/1, Dharam Karan Road, Ameerpet Hyderabad Telangana 500016 Swapna Health Care 6-3-1111/19, Nishath Bagh, Begumpet Hyderabad Telangana 500016 Basant Sahney Hospital Plot No 29/A, Road No.1, West Marredpally Secunderabad Telangana 500026 Multispeciality Sai Krishna Super Speciality 3-51,VLR Complex, Station Road, Kachiguda Hyderabad Telangana 500027 Neuro Hospital Sai Vani Hospital Ltd. 1-2-365/36/6 And 7, Ramakrishna Mutt Road,Opposite Indira Ramakrishna Mutt Hyderabad Telangana 500029 Park,Domalaguda, Sathya Kidney Centre & Super 3-6-426,Street-4, Himayath Nagar Hyderabad Telangana 500029 Speaciality Hospitals Rainbow Children's Hospital & Banjara Hills,Plot No 22, Road No 10, Banjara Hills Hyderabad Telangana 500034 Prenatal Centre Mythri Hospital 5-4/12-16,Main Road, Chanda Nagar Hyderabad Telangana 500050 Sai Ram -

Route Bus Point Pickup Drop Gb 01 Andhra Bank Begumpet

MASTER REGULAR ROUTES 2019-2020 ROUTE BUS POINT PICKUP DROP GB 01 ANDHRA BANK BEGUMPET AIRPORT 7:00 AM 3:55 PM GB 01 LIFE STYLE BEGUMPET 7:05 AM 3:45 PM GB 01 TIMES OF INDIA RD.1 BANJARA HILLS 7:10 AM 3:35 PM GB 01 DMART, OPP. MADHAPUR PS 7:15 AM 3:30 PM GB 01 KARACHI BAKERY MADHAPUR 7:21 AM 3:25 PM GB 01 RATNADEEP HITECH CITY MADHAPUR 7:25 AM 3:21 PM GB 01 MY HOME NAVADWEEPA HITECH 7:26 AM 3:20 PM GB 01 VLCC NR JAYABHERI SILICON KOTHAGUDA 7:28 AM 3:16 PM GB 01 PRESTIGE IVY LEAGUE, KOTHAGUDA 7:30 AM 3:15 PM GB 01 RATNADEEP BP RAJU MARG KOTHAGUDA 7:31 AM 3:05 PM GB 01 GOVT. SCHOOL MASJIDBANDA 7:40 AM 2:55 PM GB 01 PAVANI AQUA MASJIDBANDA 7:41 AM 2:55 PM GB 01 CYBER MEADOWS MASJIDBANDA 7:42 AM 2:56 PM GB 01 XENOPEARL APARTMENTS MASJIDBANDA 7:45 AM 2:55 PM GB 01 RELIANCE PARADISE MASJIDBANDA 7:46 AM 2:51 PM GB 01 RELIANCE PARADISE T JUNCTION 7:50 AM 2:51 PM ROUTE BUS POINT PICKUP DROP GB 02 GOVT NURSING COLLEGE RAJBHAVAN 7:00 AM 4:00 PM GB 02 MORE MEGASTORE, ERRAMANZIL 7:10 AM 3:50 PM GB 02 G V K MALL RD.1 BANJARA HILLS 7:13 AM 3:42 PM GB 02 RATNADEEP SUPERMARKET, ROAD NO.7, BANJARA HILLS 7:15 AM 3:40 PM GB 02 BANJARA HILLS ROAD NO 10 MASQUATI DAIRY PRODUCTS 7:18 AM 3:35 PM GB 02 INNER SPACE FURNITURES RD.12 BANJARA HILLS 7:25 AM 3:20 PM GB 02 L & T TOWNSHIP CLUB HOUSE 7:35 AM 3:00 PM GB 02 TELECOMNAGAR GATE NR L&T 7:40 AM 2:55 PM GB 02 TELECOMNAGAR(P) PINEVALLEY(D) GB 02 NA 2:55 PM GB 02 GREEN BAWARCHI, INDIRANAGAR 7:42 AM 2:52 PM GB 02 PARADISE TAKE AWAY GACHIBOWLI 7:45 AM 2:50 PM ROUTE BUS POINT PICKUP DROP GB 03 PILLER NO 125 NR SPENCERS ATTAPUR 7:00 AM 3:55 PM GB 03 GUDIMALKAPUR X ROADS. -

Information and Membership Directory

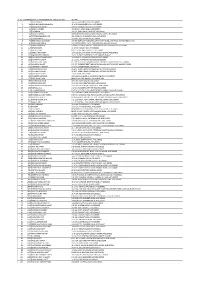

INDIAN GEOPHYSICAL UNION (IGU) Information and Membership Directory NGRI Campus, Uppal Road, Hyderabad - 500 007, INDIA E.mail: [email protected]; Website: www.iguonline.in 1 CONTENTS 1. FORMATION 3 2. MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION 4 3. RULES & BYE-LAWS 5 4. AWARDS 17 5. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 21 6. PATRONS 30 7. FOUNDATION FELLOWS 30 8. HONORARY FELLOWS 33 9. FOREIGN FELLOWS 34 10. FELLOWS 36 11. LIFE MEMBERS 65 2 INDIAN GEOPHYSICAL UNION (REGISTRATION No. 26 of 1964) Formation: The Indian Geophysical Union (IGU) was formed by circulating a letter signed by fifteen leading geophysicists of the country in the year 1963. The response to this was encouraging and about sixty geophysicists responded to this invitation. These geophysicists who enrolled themselves as Members of the Union were styled as Foundation Fellows. The Indian Geophysical Union was formally inaugurated by Prof.Humayun Kabir, the then Minister for Cultural Affairs and Scientific Research (Govt. of India) in the year 1963, at a pleasant function organized in the Geology Department, Osmania University. Dr.D.S.Reddy, the then Vice-Chancellor, Osmania University, presided over the function. Dr.S.Bhagavantam, the then Scientific Adviser to Defence Minister welcomed the guests. Dr.K.R.Ramanathan, first President of the Union, delivered the Presidential address. Dr.M.S.Krishnan explained the aims and objectives of the Union and presented the draft constitution, which was revised in 1964, it was marginally amended in 1998. Some additional information is provided in the present updated version. Dr.K.R.Ramanathan, Director, Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad and a past President of the International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics, was unanimously elected as President of the Union. -

23B Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

23B bus time schedule & line map 23B Bhudevi Nagar to secunderabad View In Website Mode The 23B bus line (Bhudevi Nagar to secunderabad) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bhudevinagar Bus Stop: 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM (2) Secunderabad: 7:08 AM - 9:29 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 23B bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 23B bus arriving. Direction: Bhudevinagar Bus Stop 23B bus Time Schedule 15 stops Bhudevinagar Bus Stop Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM Monday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM Secunderabad Bus Station (Gurudwara) Tuesday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM Saint Marys Road, 6 Wednesday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM Patny Thursday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM Jubilee Bus Station Friday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM Hps High School Saturday 7:40 AM - 10:11 PM SH1, Secunderabad Vikrampuri Bus Stop Karkhana 23B bus Info Direction: Bhudevinagar Bus Stop Karkhana Temple Arch Stops: 15 Trip Duration: 20 min Transport Road, Secunderabad Line Summary: Secunderabad Bus Station Hanuman Temple (Tirumalgherry) (Gurudwara), Saint Marys Road, 6, Patny, Jubilee Bus Station, Hps High School, Vikrampuri Bus Stop, Karkhana, Karkhana Temple Arch, Hanuman Temple RTC Colony Gun Rock Road (Tirumalgherry), RTC Colony Gun Rock Road, ravi colony road, Secunderabad Durganagar Gun Rock Road, Teachers Colony, Subash Nagar, Track Road Subashnagar, Durganagar Gun Rock Road Bhudevinagar Laststop Teachers Colony Subash Nagar Track Road Subashnagar Bhudevinagar Laststop Direction: Secunderabad 23B bus Time Schedule 15 stops Secunderabad -

Div out 2016-17.Xlsx

SL NO MEMBERSHIPNAME NO. OF THE MEMBER SRI /SMT/KUM/M/S ADDRESS 1 1 SRI B.N.RATHI 4-5-173 ,SULTAN BAZAR,,HYD,500002 2 30 HUKUMCHAND BHANGADIA 18-4-50 ,SHAMSHEER GUNJ,,HYD,500053 3 31 HARIKISHAN LAHOTI 18-4-50 ,SHAMSHEER GUNJ,,HYD,500053 4 41 NIRMALA SABOO "MANISHA" ,EDEN BAGH,,HYD,500001 5 45 R V PAHADE 3-5-141 ,EDEN BAGH RAMKOTE,,HYD,500001 6 46 KALAVATI DHOOT GOPAL BHAVAN ,BASHEER BAGH POLICE COMP,,HYD,500029 7 63 PRATIBHA MAHESHWARI 402, ROAD NO 5 ,BANJARA HILLS,,HYD,500034 8 73 SHARAYU BAJAJ 4-1-1011 ,BAGULKUNTA,,HYD,500001 9 75 GIRDHARDAS MUNDADA C/O SRI GOPINATH AGENCIES ,OPP KAMAT HOTEL,,NAMPALLY STATION ROAD,,HYD, 10 84 RAJKUMARI SARDA C/o UNITED STEELS ,10/11 PAN BAZAR,SEC-BAD,SEC,500003 11 112 BIMLA BAI MARDA 6-3-907/12 FAIRY LAKE APT ,SOMAJIGUDA RAJ BHAVAN RD,,HYD,500082 12 113 GITA BAI SONI 11-3-949 ,MALLE PALLY,,HYD,500001 13 114 MOTILAL SONI NO.11-3-949, ,MALLAPALLY,,,HYD,500001 14 118 URMILA BHANDARI 15/7/160/2 LAXMANGIRI ,MATH BEGUM BAZAR,,HYD,500012 15 120 MANKANVER CHANDAK 10-2-196 ,EAST MARREDPALLY,SEC-BAD,SEC,500026 16 128 BALA PRASAD MUNDHADA 12-11-205/1, ,WARISGUDA,SEC-BAD,SEC,500061 17 130 SHIVANATH LADHA 12-11-331 ,WARISGUDA,SEC-BAD,SEC,500061 18 131 NANDKISHORE BUNG PLT.NO.16, ,RADHE SWAMY COLONY,,SIKH ROAD,BOWENPALLY,SEC,500009 19 135 USHADEVI BAHETI 8-2-171 TURNER STREET ,BEHIND EMMANUEL PH STUDIO,SEC-BAD,SEC,500003 20 136 CHTRABHUJ CHANDAK 6-1-606 ,KHAIRATABAD,,HYD,500004 21 148 HARIKISHAN MALANI 25-B ST.