Pseudomys Oralis (Hastings River Mouse)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calaby References

Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents; Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs; Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents; Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents; Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores; Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Factsheet: a Threatened Mammal Index for Australia

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 3.1 Factsheet: A Threatened Mammal Index for Australia Research in brief How can the index be used? This project is developing a For the first time in Australia, an for threatened plants are currently Threatened Species Index (TSX) for index has been developed that being assembled. Australia which can assist policy- can provide reliable and rigorous These indices will allow Australian makers, conservation managers measures of trends across Australia’s governments, non-government and the public to understand how threatened species, or at least organisations, stakeholders and the some of the population trends a subset of them. In addition to community to better understand across Australia’s threatened communicating overall trends, the and report on which groups of species are changing over time. It indices can be interrogated and the threatened species are in decline by will inform policy and investment data downloaded via a web-app to bringing together monitoring data. decisions, and enable coherent allow trends for different taxonomic It will potentially enable us to better and transparent reporting on groups or regions to be explored relative changes in threatened understand the performance of and compared. So far, the index has species numbers at national, state high-level strategies and the return been populated with data for some and regional levels. Australia’s on investment in threatened species TSX is based on the Living Planet threatened and near-threatened birds recovery, and inform our priorities Index (www.livingplanetindex.org), and mammals, and monitoring data for investment. a method developed by World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological A Threatened Species Index for mammals in Australia Society of London. -

Rodents Bibliography

Calaby’s Rodent Literature Abbott, I.J. (1974). Natural history of Curtis Island, Bass Strait. 5. Birds, with some notes on mammal trapping. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 107: 171–74. General; Rodents Abbott, I. (1978). Seabird islands No. 56 Michaelmas Island, King George Sound, Western Australia. Corella 2: 26–27. (Records rabbit and Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents; Lagomorphs Abbott, I. (1981). Seabird Islands No. 106 Mondrain Island, Archipelago of the Recherche, Western Australia. Corella 5: 60–61. (Records bush-rat and rock-wallaby). General; Rodents Abbott, I. and Watson, J.R. (1978). The soils, flora, vegetation and vertebrate fauna of Chatham Island, Western Australia. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 60: 65–70. (Only mammal is Rattus fuscipes). General; Rodents Adams, D.B. (1980). Motivational systems of agonistic behaviour in muroid rodents: a comparative review and neural model. Aggressive Behavior 6: 295–346. Rodents Ahern, L.D., Brown, P.R., Robertson, P. and Seebeck, J.H. (1985). Application of a taxon priority system to some Victorian vertebrate fauna. Fisheries and Wildlife Service, Victoria, Arthur Rylah Institute of Environmental Research Technical Report No. 32: 1–48. General; Marsupials; Bats; Rodents; Whales; Land Carnivores Aitken, P. (1968). Observations on Notomys fuscus (Wood Jones) (Muridae-Pseudomyinae) with notes on a new synonym. South Australian Naturalist 43: 37–45. Rodents; Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. (ed.) The natural history of the Flinders Ranges. Libraries Board of South Australia : Adelaide. (Gives descriptions and notes on the echidna, marsupials, murids, and bats recorded for the Flinders Ranges; also deals with the introduced mammals, including the dingo). -

Development and Application of Survey Methods to Determine

Development and application of survey methods to determine habitat use in relation to forest management and habitat characteristics of the endangered numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) in the Upper Warren region, Western Australia by Anke Seidlitz BSc (Hons) A thesis submitted to Murdoch University to fulfil the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the discipline of Environmental and Conservation Sciences January 2021 Author’s declaration I declare that (a) the thesis is my own account of my research, except where other sources are acknowledged, (b) all co-authors, where stated and certified by my principal supervisor or executive author, have agreed that the works presented in this thesis represent substantial contributions from myself and (c) the thesis contains as its main content work that has not been previously submitted for a degree at any other university. ……………………………. Anke Seidlitz i Abstract Effective detection methods and knowledge on habitat requirements is key for successful wildlife monitoring and management. The numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) is an endangered, Australian-endemic marsupial that has experienced major population declines since European settlement. The Upper Warren region (UWR) in south-western Australia contains one of the two remaining natural populations. A lack of effective survey methods has caused a paucity of information regarding this population. This PhD project aimed to develop robust survey methods and determine habitat requirements for the numbat in the UWR. Given the perceived advantages of camera trap technology in wildlife research, camera trap trials were conducted to optimise camera methodologies for numbat detection. Swift 3C wide-angle camera traps positioned at ~25 cm above ground increased numbat detections by 140% compared to commonly used Reconyx PC900 camera traps. -

Psmissen Phd Thesis

Evolutionary biology of Australia’s rodents, the Pseudomys and Conilurus Species Groups Peter J. Smissen Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 School of BioSciences Faculty of Science University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper 1 Dedicated to my parents: Ian and Joanne Smissen. 2 Abstract The Australian rodents represent terminal expansions of the most diverse family of mammals in the world, Muridae. They colonised New Guinea from Asia twice and Australia from New Guinea several times. They have colonised all Australian terrestrial environments including deserts, forests, grasslands, and rivers from tropical to temperate latitudes and from sea level to highest peaks. Despite their ecological and evolutionary success Australian rodents have faced an exceptionally high rates of extinction with >15% of species lost historically and most others currently threatened with extinction. Approximately 50% of Australian rodents are recognised in the Pseudomys Division (Musser and Carleton, 2005), including 3 of 10 historically extinct species. The division is not monophyletic with the genera Conilurus, Mesembriomys, and Leporillus (hereafter Conilurus Species Group, CSG) more closely related to species of the Uromys division to the exclusion of Zyzomys, Leggadina, Notomys, Pseudomys and Mastacomys (hereafter Pseudomys Species Group, PSG). In this thesis, I resolved phylogenetic relationships and biome evolution among living species of the PSG, tested species boundaries in a phylogeographically-structured species, and incorporated extinct species into a phylogeny of the CSG. To resolve phylogenetic relationships within the Pseudomys Species Group (PSG) I used 10 nuclear loci and one mitochondrial locus from all but one of the 33 living species. -

The Ecology and Conservation of the Water Mouse (Xeromys Myoides) Along the Maroochy River Catchment in Southeast Queensland

The ecology and conservation of the water mouse (Xeromys myoides) along the Maroochy River Catchment in southeast Queensland. Janina Lyn Deborah Kaluza Bachelor of Environmental Science A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 School of Agriculture, Food and Sciences i Abstract The water mouse is one of Australia’s most enigmatic, intriguing and little-known vertebrate species. It is also in decline and confronted with a wide range of threats. Locally, the demise of one water mouse population along the Coomera River was documented in 2006 within an area where urban and industrial development pressures are paramount for this species and their associated habitat. Improvement of its conservation status is supported by a National Recovery Plan aimed at habitat protection. However, direct human actions threatening water mouse recovery are poorly monitored and inhibit conservation efforts. Therefore, new research methods are required that include an understanding of population dynamics, gestation cycles, but most importantly, the life span of this elusive species as the additional knowledge on this species association to habitat is critical to its survival. In order to address these deficiencies, logically developed research projects form the framework of this thesis that link new locality records of the species distribution and density across southeast Queensland. The exhausted survey efforts located 352 nests in coastal wetlands between Eurimbula National Park and the Pumicestone Passage to determine the species nest structure and association with plant presence. Consistent monitoring of individual water mouse nests investigated nest building and seasonal behavior; movements and habitat use of the water mouse; impacts and management of foxes, pigs and cats within water mouse territory. -

Population Processes in an Early Successional Heathland: a Case Study of the Eastern Chestnut Mouse (Pseudomys Gracilicaudatus)

Population processes in an early successional heathland: a case study of the eastern chestnut mouse (Pseudomys gracilicaudatus) by Felicia Pereoglou A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University March 2016 Grarock K., Introduction, spread, impact and control of the common myna Grarock K., Introduction, spread, impact and control of the common myna Candidate's Declaration This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. The research, analysis and writing in the thesis are substantially (>90%) my own work. To the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. Felicia Pereoglou Date: 14 March 2016 Pereoglou, F., Population processes in an early successional heathland iii Acknowledgements I thank all the people who have dedicated their time, provided motivation, support and advice during the course of this work. I sincerely thank the members of my supervisory panel – Professor David B. Lindenmayer, Dr Sam Banks, Mr Christopher MacGregor, Dr Jeffrey Wood, and Dr Fred Ford – for their guidance and support. In particular, Sam and Chris who without your assistance through those particularly tough times, I would not have completed this work at all. I also extend thanks to; The volunteers who assisted with fieldwork surveys. A very special thanks to Wendy Hartman who made those many early mornings and nest assessments so much more -

An Overdue Break up of the Rodent Genus Pseudomys Into Subgenera As Well As the Formal Naming of Four New Species

30 Australasian Journal of Herpetology Australasian Journal of Herpetology 49:30-41. Published 6 August 2020. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) An overdue break up of the rodent genus Pseudomys into subgenera as well as the formal naming of four new species. LSIDURN:LSID:ZOOBANK.ORG:PUB:627AB9F7-5AD1-4A44-8BBE-E245C4A3A441 RAYMOND T. HOSER LSIDurn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F9D74EB5-CFB5-49A0-8C7C-9F993B8504AE 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 1 May 2020, Accepted 8 July 2020, Published 6 August 2020. ABSTRACT An audit of all previously named species and synonyms within the putative genus of Australian mice Pseudomys (including genera phylogenetically included within Pseudomys in recent studies) found a number of distinctive and divergent species groups. Some of these groups have been treated by past authors as separate genera (e.g. Notomys Lesson, 1842) and others as subgenera (e.g. Thetomys Thomas, 1910). Other groups have been recognized (e.g. as done by Ford 2006), but remain unnamed. This paper assessed the current genus-level classification of all species and assigned them to species groups. Due to the relatively recent radiation and divergence of most species groups being around the five million year mark (Smissen 2017), the appropriate level of division was found to be subgenera. As a result, eleven subgenera are recognized, with five formally named for the first time in accordance with the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Ride et al. 1999). -

Australian Rodents Reveal Conserved Cranial Evolutionary Allometry Across 10

Manuscript Copyright The University of Chicago 2020. Preprint (not copyedited or formatted). Please use DOI when citing or quoting. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/711398 Australian rodents reveal conserved Cranial Evolutionary Allometry across 10 million years of murid evolution Ariel E. Marcy1*, Thomas Guillerme2, Emma Sherratt3, Kevin C. Rowe4,5, Matthew J. Phillips6, and Vera Weisbecker1,7 1University of Queensland, School of Biological Sciences; University of Sheffield, Department of Animal and Plant Sciences; 3University of Adelaide, School of Biological Sciences, 4Museums Victoria, Sciences Department; 5University of Melbourne, School of BioSciences; 6Queensland University of Technology, School of Biology & Environmental Science; 7Flinders University, College of Science and Engineering; *[email protected] Keywords: allometric facilitation, CREA, geometric morphometrics, molecular phylogeny, Murinae, stabilizing selection 1 Copyright The University of Chicago 2020. Preprint (not copyedited or formatted). Please use DOI when citing or quoting. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/711398 ABSTRACT Among vertebrates, placental mammals are particularly variable in the covariance between cranial shape and body size (allometry), with rodents a major exception. Australian murid rodents allow an assessment of the cause of this anomaly because they radiated on an ecologically diverse continent notably lacking other terrestrial placentals. Here we use 3D geometric morphometrics to quantify species-level and evolutionary allometries in 38 species (317 crania) from all Australian murid genera. We ask if ecological opportunity resulted in greater allometric diversity compared to other rodents, or if conserved allometry suggests intrinsic constraints and/or stabilizing selection. We also assess whether cranial shape variation follows the proposed “rule of craniofacial evolutionary allometry” (CREA), whereby larger species have relatively longer snouts and smaller braincases. -

Smoky Mouse Pseudomys Fumeus

Action Statement FloraFlora and and Fauna Fauna Guarantee Guarantee Act Act 1988 1988 No. No. ### 196 Smoky Mouse Pseudomys fumeus Description and distribution The Smoky Mouse Pseudomys fumeus is a small native rodent about 2-3 times the size of the introduced House Mouse. Its fur is pale smoky grey above and whitish below. The tail is long, narrow, flexible and sparsely furred. The tail colour is pale pinkish grey with a narrow dark stripe along its upper surface. The ears and feet are flesh-coloured with sparse white hair. Total length varies from 180 mm to 250 mm with the tail accounting for more than half of this. The ears are 18-22 mm long and the hind feet 25-29 mm. Adult weight varies widely, from 25 g to 86 g. Animals from The Grampians and Otway Range in western Victoria tend to be larger and darker than Smoky Mouse (Pseudomys fumeus) those from east of Melbourne (Menkhorst and (Photo: DSE/McCann) Knight 2001, Menkhorst and Seebeck unpublished data). Victorian records of the Smoky Mouse fall into five distinct Victorian biogeographic regions: Greater Grampians, Otway Ranges, Highlands (both northern and southern falls), Victorian Alps and East Gippsland Lowlands. It is not certain that the species persists in all of these regions, as recent targeted surveys have failed to detect it in the East Gippsland Lowlands and the Otway Ranges (Menkhorst and Homan unpublished). Habitat The precise habitat requirements of the Smoky Mouse are far from clear. A wide range of vegetation communities are occupied, from damp coastal heath to sub-alpine heath. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Therya ISSN: 2007-3364 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste Woinarski, John C. Z.; Burbidge, Andrew A.; Harrison, Peter L. A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals Therya, vol. 6, no. 1, January-April, 2015, pp. 155-166 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237 Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=402336276010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative THERYA, 2015, Vol. 6 (1): 155-166 DOI: 10.12933/therya-15-237, ISSN 2007-3364 Una revisión del estado de conservación de los mamíferos australianos A review of the conservation status of Australian mammals John C. Z. Woinarski1*, Andrew A. Burbidge2, and Peter L. Harrison3 1National Environmental Research Program North Australia and Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environmental Science Programme, Charles Darwin University, NT 0909. Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (JCZW) 2Western Australian Wildlife Research Centre, Department of Parks and Wildlife, PO Box 51, Wanneroo, WA 6946, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (AAB) 3Marine Ecology Research Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, PO Box 157, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (PLH) *Corresponding author Introduction: This paper provides a summary of results from a recent comprehensive review of the conservation status of all Australian land and marine mammal species and subspecies. -

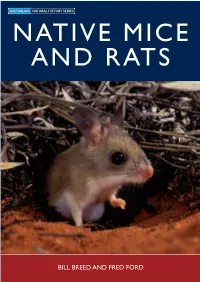

NATIVE MICE and RATS BILL BREED and FRED FORD NATIVE MICE and RATS Photos Courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman

AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD BILL BREED AND RATS MICE NATIVE NATIVE MICE AND RATS Photos courtesy Jiri Lochman,Transparencies Lochman Australia’s native rodents are the most ecologically diverse family of Australian mammals. There are about 60 living species – all within the subfamily Murinae – representing around 25 per cent of all species of Australian mammals.They range in size from the very small delicate mouse to the highly specialised, arid-adapted hopping mouse, the large tree rat and the carnivorous water rat. Native Mice and Rats describes the evolution and ecology of this much-neglected group of animals. It details the diversity of their reproductive biology, their dietary adaptations and social behaviour. The book also includes information on rodent parasites and diseases, and concludes by outlining the changes in distribution of the various species since the arrival of Europeans as well as current conservation programs. Bill Breed is an Associate Professor at The University of Adelaide. He has focused his research on the reproductive biology of Australian native mammals, in particular native rodents and dasyurid marsupials. Recently he has extended his studies to include rodents of Asia and Africa. Fred Ford has trapped and studied native rats and mice across much of northern Australia and south-eastern New South Wales. He currently works for the CSIRO Australian National Wildlife Collection. BILL BREED AND FRED FORD NATIVE MICE AND RATS Native Mice 4thpp.indd i 15/11/07 2:22:35 PM Native Mice 4thpp.indd ii 15/11/07 2:22:36 PM AUSTRALIAN NATURAL HISTORY SERIES NATIVE MICE AND RATS BILL BREED AND FRED FORD Native Mice 4thpp.indd iii 15/11/07 2:22:37 PM © Bill Breed and Fred Ford 2007 All rights reserved.