Phosphor-Free Ingan White Light Emitting Diodes Using Flip-Chip Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isamu Akasaki(Professor at Meijo University

Nanotechnology and Materials (FY2016 update) Meeting the challenge of "impossible" technology Succeeded in the practical implementation of blue light-emitting diode! Research in the unattainable territory that won the Nobel Prize The 2014 Nobel Physics Prize was presented to blue LED. The development of blue LED resulted in the three researchers, Professor Isamu Akasaki, Professor commercialization of much brighter and energy-saving Hiroshi Amano and Professor Shuji Nakamura for the white light, thus contributing to energy conservation invention of an efficient blue light-emitting diode (LED). in the world and an improvement of people's lives in Red LEDs and yellow-green LEDs were developed in the areas without sufficient electricity. In addition to their 1960s; however, practical implementation of blue LEDs use as light sources, blue LEDs are now being widely was so difficult that it was even said that "it would be applied in various fields such as information technology, impossible to realize blue LEDs by the end of the 20th transportation, medicine and agriculture. Additionally, century." Amid such a circumstance, Professor Akasaki, the technology to put gallium nitride into practical Professor Amano and Professor Nakamura worked on implementation developed by the three researchers is the high-quality single crystallization and the p-type expected to find various applications in the future, such doping of gallium nitride (GaN), both of which had been as an application in power devices that serve as electric given up by researchers around the world. Their efforts power converters in electric vehicles and smart grids, from the 1980s to the 1990s finally led to their success next-generation power distribution grids,. -

Migration Enhanced Plasma Assisted Metal Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition of Indium Nitride

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Physics and Astronomy Dissertations Department of Physics and Astronomy 5-4-2020 MIGRATION ENHANCED PLASMA ASSISTED METAL ORGANIC CHEMICAL VAPOR DEPOSITION OF INDIUM NITRIDE Zaheer Ahmad Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/phy_astr_diss Recommended Citation Ahmad, Zaheer, "MIGRATION ENHANCED PLASMA ASSISTED METAL ORGANIC CHEMICAL VAPOR DEPOSITION OF INDIUM NITRIDE." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/phy_astr_diss/123 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Physics and Astronomy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIGRATION ENHANCED PLASMA ASSISTED METAL ORGANIC CHEMICAL VAPOR DEPOSITION OF INDIUM NITRIDE by ZAHEER AHMAD Under the Direction of Alexander Kozhanov, PhD ABSTRACT The influence of various plasma species on the growth and structural properties of indium nitride in migration-enhanced plasma-assisted metalorganic chemical vapor deposition (MEPA- MOCVD). The atomic nitrogen ions’ flux has been found to have a significant effect on the growth rate as well as the crystalline quality of indium nitride. No apparent effect of atomic neutrals, molecular ions, and neutral nitrogen molecules has been observed on either the growth rate or crystalline quality. A thermodynamic supersaturation model for plasma-assisted metalorganic chemical vapor deposition of InN has also been developed. The model is based on the chemical combination of indium with plasma-generated atomic nitrogen ions. In supersaturation was analyzed for indium nitride films grown by PA-MOCVD with varying input flow of indium precursor. -

Indium Gallium Nitride: Light Emitting Diodes and Beyond

Indium gallium nitride: Light emitting diodes and beyond Rachel A. Oliver Department of Materials Science and Metallurgy, University of Cambridge Light emitting diodes (LEDs) exploiting indium gallium nitride (InGaN) quantum wells for light emission in the green, blue and near ultra-violet regions of the spectrum have been a huge commercial success. However, their effectiveness remains something of a mystery to researchers, since the GaN pseudo-substrates on which they are typically grown are riddled with threading dislocations which act as non-radiative recombination centres and should thus quench light emission. Some microstructural feature of the quantum wells is believed to prevent exciton diffusion to dislocation cores. In this presentation, I will explore various attempts to identify the key microstructural feature, including the problems which arise in using TEM to examine InGaN, due to the damage wrought on the sample by the electron beam. We have attempted to overcome these problems by using an alternative technique: three-dimensional atom probe (3DAP), and I will present the first 3DAP pictures of nitride samples, and show how they provide insights into the nano- and meso- scale microstructure of the InGaN quantum wells. Whilst InGaN-based LEDs are widely available, there may be other opportunities for this material in novel devices. In the second part of my talk, I will introduce our recent work on single photon sources based on InGaN quantum dots, and discuss the challenges that the nitride materials system brings to the construction of such devices. I will demonstrate the application of InGaN quantum dots in an optically pumped blue-emitting single photon source, and discuss the potential advantages of such a source and the hurdles which still need to be overcome before a commercially viable device can be developed. -

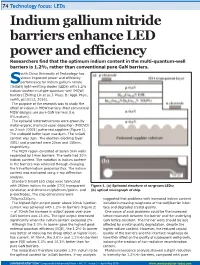

Indium Gallium Nitride Barriers Enhance LED Power and Efficiency

74 Technology focus: LEDs Indium gallium nitride barriers enhance LED power and efficiency Researchers find that the optimum indium content in the multi-quantum-well barriers is 1.2%, rather than conventional pure GaN barriers. outh China University of Technology has shown improved power and efficiency Sperformance for indium gallium nitride (InGaN) light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with 1.2% indium-content multiple-quantum-well (MQW) barriers [Zhiting Lin et al, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., vol49, p115112, 2016]. The purpose of the research was to study the effect of indium in MQW barriers. Most commercial MQW designs use pure GaN barriers (i.e. 0% indium). The epitaxial heterostructures were grown by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) on 2-inch (0001) patterned sapphire (Figure 1). The undoped buffer layer was 4µm. The n-GaN contact was 3µm. The electron-blocking layer (EBL) and p-contact were 20nm and 150nm, respectively. The MQW region consisted of seven 3nm wells separated by 14nm barriers. The wells had 20% indium content. The variation in indium content in the barriers was achieved through changing the trimethyl-indium precursor flux. The indium content was evaluated using x-ray diffraction analysis. Standard InGaN LED chips were fabricated with 250nm indium tin oxide (ITO) transparent Figure 1. (a) Epitaxial structure of as-grown LEDs; conductor, and chromium/platinum/gold n- and (b) optical micrograph of chip. p-electrodes. The chip dimensions were 750µmx220µm. suggested that problems with increased indium content The highest light output power above 20mA injection included increasing roughness of the well/barrier inter- current was achieved with 1.2%-In barriers (Figure 2) face and degraded crystal quality. -

Algan UV-Leds

Inkohärente Lichtquellen Sommersemester 2010 Uli Engelhardt und Kai Kruse Outline 1. Introduction: Light Emitting Diodes History Principle/ assembly Applications 2. UV - LEDs Different types Applications 3. AlGaN UV - LEDs Technical Details Development/outlook 1. Introduction: Light Emitting Diodes History 1907: H. J. Round of Marconi Labs discovered that some inorganic substances glow if a electric voltage is impress on them. 1927: The russian Oleg Vladimirovich Losev independently reported on the creation of an LED, but no practical use was made of the discovery. 1961: Bob Biardand and Gary Pittman (Texas Instruments) find out that gallium arsenide (GaAs) give off infrared radiation when electric current is applied. They receive a patent for this diode. 1. Introduction: Light Emitting Diodes History 1962: First visible red GaAsP-LEDs was developed by Nick Holonyak ("father of the light-emitting diode”) at General Electric Company. 1971: The first blue LEDs (GaN) were made by Jacques Pankove at RCA Laboratories. Too little light output to be of much practical use. 1993: Shuji Nakamura (Nichia Corporation) demonstrates the first high-brightness blue LED based on InGaN. Blaue LEDs aus InGaN 1. Introduction: Light Emitting Diodes Principle LED consists of a chip of semiconducting material with a p-n junction. As in other diodes, current flows easily from the p-side (anode) to the n-side (cathode), but not in the reverse direction. At the barrier layer electrons and holes recombinat and energy in the form of a photon is emitting. The wavelength of the light, depends on the band gap energy. 1. Introduction: Light Emitting Diodes Principle Color Wavelength (nm) Semiconductor Material Infrared > 760 e.g.: GaAs, AlGaAs Red 610 - 760 e.g.: AlGaAs, AlGaInP Orange 590 - 610 e.g.: GaAsP, GaP Yellow 570 - 590 e.g.: GaAsP, GaP Green 500 - 570 e.g.: InGaN, GaN Blue 450 - 500 e.g.: ZnSe, InGaN Ultraviolet < 400 e.g.: AlN AlGaN AlGaInN 1. -

Indium Nitride Growth by Metal-Organic Vapor Phase Epitaxy

INDIUM NITRIDE GROWTH BY METAL-ORGANIC VAPOR PHASE EPITAXY By TAEWOONG KIM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Taewoong Kim ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes first to thank his advisor, Dr. Timothy J. Anderson, for providing five years of valuable advice and guidance. Dr. Anderson always encouraged the author to approach his research from the highest scientific level. He is deeply thankful to his co-advisor, Dr. Olga Kryliouk, for her valuable guidance, sincere advice, and consistent support for the past five years. Secondly, the author wishes to thank the remaining committee members of Dr. Steve Pearton and Dr. Fan Ren for their advice and guidance The author is grateful to Scott Gapinski, the staff at Microfabritech, and Eric Lambers, the staff at the Major Analytical Instrumentation Center, especially for Auger characterization. Acknowledgement needs to be given to Sangwon Kang who worked with the author for the past year and provided valuable assistance. Thanks go to Youngsun Won for his useful discussion of quantum calculation and SEM characterization, and to Dr. Jianyun Shen for her assistance about how to use the ThermoCalc. The author wishes to thank Hyunjong Park for useful discussion and Youngseok Kim for his kindness and friendship. Most importantly, the author is grateful to Moonhee Choi, his beloved wife, for her endless support, trust, love, sacrifice and encouragement. Without her help, he would have not finished the Ph.D. course. iii The author is grateful to his mother, father, mother-in-law, father-in-law, sisters, and brother for providing love, support and guidance throughout his life. -

LIGHT-EMITTING DIODES: Zno Does Away with Green-LED Problem

LIGHT-EMITTING DIODES: ZnO does away with green-LED problem While blue and red LEDs can be made to shine brilliantly and have a long life, high-brightness green LEDs tend to die early. Now, scientists at Northwestern University (Evanston, IL) and Nanovation SARL (Orsay, France) have developed a type of green LED that has the potential to burn brightly while enduring year after year. Still in the early prototype stage, the LED has a different makeup that keeps the indium within its diode structure from diffusing over time and reducing the diode’s light output.1 The prime mover for the research is solid-state lighting. One of the most efficient forms of LED lighting is based on a combination of ultrabright blue, green, and red LEDs, which, in the right proportions, can produce white light without the use of phosphors. Both blue and green LEDs are based on an indium gallium nitride (InGaN) diode structure; increasing the amount of In within the active layers shifts the output toward longer wavelengths, making green emission practical. However, if the indium content is high enough the InGaN layer becomes unstable at elevated temperatures, causing the LED to dim or burn out. Although such temperatures are much higher than a green LED would ever experience in operation, the LED fabrication process itself reaches these temperatures. Thus, high-brightness green LEDs begin their existence with a built-in handicap. Zinc oxide on top The problem is the p-GaN layer, which is the last layer grown; because it has the highest fabrication temperature of all the layers, its deposition destabilizes the InGaN light-emitting layer below. -

Indium Gallium Nitride Multijunction Solar Cell Simulation Using Silvaco Atlas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-06 Indium gallium nitride multijunction solar cell simulation using silvaco atlas Garcia, Baldomero Monterey California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3423 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS INDIUM GALLIUM NITRIDE MULTIJUNCTION SOLAR CELL SIMULATION USING SILVACO ATLAS by Baldomero Garcia, Jr. June 2007 Thesis Advisor: Sherif Michael Second Reader: Todd Weatherford Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Indium Gallium Nitride 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Multijunction Solar Cell Simulation Using Silvaco Atlas 6. AUTHOR(S) Baldomero Garcia, Jr. 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

GROWTH OPTIMIZATION and PROCESS DEVELOPMENT of INDIUM GALLIUM NITRIDE/GALLIUM NITRIDE SOLAR CELLS Matthew Jordan

GROWTH OPTIMIZATION AND PROCESS DEVELOPMENT OF INDIUM GALLIUM NITRIDE/GALLIUM NITRIDE SOLAR CELLS Matthew Jordan To cite this version: Matthew Jordan. GROWTH OPTIMIZATION AND PROCESS DEVELOPMENT OF INDIUM GALLIUM NITRIDE/GALLIUM NITRIDE SOLAR CELLS. Engineering Sciences [physics]. École Doctorale de génie électrique et informatique, 2017. English. tel-02433343 HAL Id: tel-02433343 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02433343 Submitted on 9 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GROWTH OPTIMIZATION AND PROCESS DEVELOPMENT OF INDIUM GALLIUM NITRIDE/GALLIUM NITRIDE SOLAR CELLS AThesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Matthew B. Jordan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology May, 2017 Copyright c 2017 by Matthew B. Jordan GROWTH OPTIMIZATION AND PROCESS DEVELOPMENT OF INDIUM GALLIUM NITRIDE/GALLIUM NITRIDE SOLAR CELLS Approved by: Dr. Abdallah Ougazzaden, Advisor Dr. David Citrin Director, Co-President, Professor Professor, ECE Georgia Tech Lorraine, UMI GT- Georgia Institute of Technology CNRS, Institut Lafayette Dr. Paul Voss Dr. Thomas Sanders Associate Professor, ECE Regents Professor, MSE Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. -

Molecular Beam Epitaxy Growth of Inn and Ingan Materials

Molecular Beam Epitaxy Growth of Indium Nitride and Indium Gallium Nitride Materials for Photovoltaic Applications A Ph.D. Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty by Elaissa Trybus In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology May 2009 Copyright 2009 by Elaissa Trybus Molecular Beam Epitaxy Growth of Indium Nitride and Indium Gallium Nitride Materials for Photovoltaic Applications Dr. W. Alan Doolittle School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Ian Ferguson School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Ajeet Rohatgi School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Shyh-Chiang Shen School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Samuel Graham School of Mechanical Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: March 2009 ii To my parents. This would not have been possible without your support. iii Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you’ve imagined. -Henry David Thoreau iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My interest in math and science was fostered by my Dad, the Physicist. I would not be an Electrical Engineer (AKA an applied Physicist) without his instruction and support. I thank both my parents for their never ending love and support. My advisor, Dr. W. Alan Doolittle has been very supportive, patient, and provided me with endless knowledge. I am extremely grateful to him. Additionally, the members of his research group have been invaluable to me in friendship and with my education: Walter Henderson, David Pritchett, Alex Carver, Daniel Billingsley, Laws Calley, Michael Moseley, Kyoung Keun Lee, Ann Trippe, Dr. -

Indium Gallium Nitride Laser with N-Type Ridge on Silicon an Inverted Diode Structure Has Been Shown to Slash Joule Heating and Boost Thermal Management

60 Technology focus: Lasers Indium gallium nitride laser with n-type ridge on silicon An inverted diode structure has been shown to slash Joule heating and boost thermal management. hina’s Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano- based complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor Bionics (SINANO) has fabricated indium gallium (CMOS) mainstream electronics and could be used Cnitride (InGaN) violet-emitting laser diodes in monolithically integrated silicon photonics as an (LDs) on silicon with n-type ridge waveguides (nRWs), efficient on-chip light source for high-speed data com- which demonstrated lower electrical resistance and munication and computation. improved thermal performance over pRW-LDs Magnesium (Mg) is the usual p-type dopant in [Rui Zhou et al, ACS Photonics vol7 (2020), issue 10, III–nitride structures. This imposes a number of p2636 (23 September 2020)]. Normally, process limi- restrictions in the growth and activation annealing tations dictate that the RW in InGaN-based laser diodes required to create p-type conductivity. First, Mg tends are on the p-side of the device. The thermal and elec- to hang around in reaction chambers. This ‘memory trical problems arise because p-GaN is much more effect’ means that subsequent layers will have some resistive than n-GaN. level of Mg incorporation, whether desired or not. The team, which also included a researcher from The memory effect therefore tends to result in growth Tsinghua University in China, believes that nRW-LD processes being designed with p-type layers being devices could be fully compatible with large-scale silicon- grown last. Figure 1. Cross-sectional images of nRW-LD structures. -

Reducing Laser Diode Optical Leakage with Indium Gallium Nitride

72 Technology focus: Nitride lasers Reducing laser diode optical leakage with indium gallium nitride waveguides Researchers in Poland show how layers with more than 5% indium content can be used to eliminate mode leakage with relatively thin cladding. nstitute of High Pressure Physics (IHPP) and TopGaN Ltd, both of IPoland, have been jointly devel- oping indium gallium nitride (InGaN) waveguide structures for use in blue laser diodes (LDs) [Grzegorz Muziol et al, Appl. Phys. Express, vol9, p092103, 2016)]. The aim is to improve beam quality for appli- cations such as data storage and image projectors. Beam quality in III-nitride semicon- ductor laser diodes suffers because of optical leakage to the substrate through the bottom aluminium gallium nitride (AlGaN) cladding. Thicker cladding layers reduce leakage, but the thickness of AlGaN layers is restricted for coherent straining to GaN and for avoiding the cracking of epitaxial layers. The IHPP/TopGaN team proposes the use of InGaN waveguides with thickness and indium content sufficient to increase the effective refractive index to greater than that of GaN. This should not only reduce leakage, but fully suppress it, according to the researchers. They comment: “The most important advantage of this design is that a thick n-AlGaN cladding is not neces- sary to obtain high optical beam quality.” Figure 1. Schematic design of laser diode. The researchers used plasma- assisted molecular beam epitaxy (PAMBE) to grow the without waveguide layers. material for blue laser diodes with InGaN waveguides The far-field profiles were assessed using a CCD (Figure 1). Eight different InGaN waveguide structures camera (Figure 2).