The Question of Ancient Scandinavian Cultic Build- Ings: with Particular Reference to Old Norse Hof1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIDSLINJE Melhus Kommune

TIDSLINJE Melhus kommune Historiene bak bildene Prosjekteier: Kultur og fritid, Melhus kommune Tegninger: Kjetil Strand Tekst: Ronald Nygård Vedlegg 2 til Melhus kommunes kulturminneplan ISTID 16000 f.kr. Fra siste istid har vi synlige eksempler på hvordan isen har formet landskapet gjennom terrassene på Hovin og Gimse. Tar vi turen opp til toppen av sandtaket på Søberg, 170 meter over nåværende havnivå, kan vi plukke skjell som synlige bevis på den kraftige landhevningen som har funnet sted. Siste istid startet for omkring 70.000 år siden. Landet var dekket av is, men sannsynligvis stakk noen nunataker (fjelltopper) opp gjennom isen på Vestlandet og i Nord-Norge. Klimaforandringer for ca. 15.000 år siden gjorde at de enorme ismassene startet å smelte. Klimasvingninger i denne perioden gjorde at isen vekselvis trakk seg tilbake, rykket frem, eller lå i ro. Utenfor isen ble det avsatt store mengder sand og grus, enten som morenerygger eller som store, flate deltaavsetninger i hav og fjorder fremfor brefronten. Landet ble presset ned av den enorme vekten av isen. Etter hvert som iskanten trakk seg tilbake, fulgte havet etter. Områder som i dag er tørt land, lå i en periode under vann/hav. Da isen smeltet, startet landet å heve seg igjen. Landet hevet seg mest i de indre strøk, der isen hadde vært tykkest. Det høyeste nivået havet stod på, kunne være over 200 meter over dagens havnivå (marin grense). De siste isrestene smeltet vekk for ca. 8500 år siden. Fra 8000 til 5000 år før nåtid, var klimaet mer gunstig, og fjellområder som i dag er nakne, var dekket av skog. -

Horg, Hov and Ve – a Pre-Christian Cult Place at Ranheim in Trønde- Lag, Norway, in the 4Rd – 10Th Centuries AD

Preben Rønne Horg, hov and ve – a pre-Christian cult place at Ranheim in Trønde- lag, Norway, in the 4rd – 10th centuries AD Abstract In the summer of 2010 a well-preserved cult place was excavated at Ranheim on Trondheim Fjord, in the county of Sør-Trøndelag, Norway. The site consisted of a horg in the form of a flat, roughly circular stone cairn c.15 m in diameter and just under 1 m high, a hov in the form of an almost rectangular building with strong foundations, and a processional avenue marked by two stone rows. The horg is presumed to be later than c. AD 400. The dating of the hov is AD 895–990 or later, during a period when several Norwegian kings reigned, including Harald Hårfager (AD 872–933), and when large numbers of Norwegians emigrated and colonized Iceland and other North Atlantic islands between AD 874 and AD 930 in response to his ruth- less regime. The posts belonging to the hov at Ranheim had been pulled out and all of the wood removed, and the horg had been carefully covered with stones and clay. Thereafter, the cult place had been entirely covered with earth, presumably during the time of transition to Christianity, and was thus effectively concealed and forgotten until it was excavated in 2010. Introduction Since the mid-1960s until about 2000 there has have been briefly mentioned by Lars Larsson been relatively little research in Scandinavia fo- in Antiquity in connection with his report on cusing on concrete evidence for Norse religion a ritual building at Uppåkra in Skåne (Larsson from religious sites, with the exception of Olaf 2007: 11–25). -

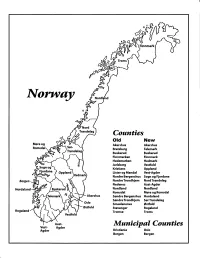

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Tectonic Features of an Area N.E. of Hegra, Nord-Trøndelag, and Their Regional Significance — Preliminary Notes by David Roberts

Tectonic Features of an Area N.E. of Hegra, Nord-Trøndelag, and their regional Significance — Preliminary Notes By David Roberts Abstract Following brief notes on the low-grade metasediments occurring in an area near Hegra, 50 km east of Trondheim, the types of structures associated with three episodes of deformation of main Caledonian (Silurian) age are described. An outline of the suggested major stmctural picture is then presented. In this the principal structure is seen as a WNW-directed fold-nappe developed from the inverted western limb of the central Stjørdalen Anticline. A major eastlward closing recumbent syncline underlies this nappe-like structure. These initial structures were then deformed by at least twofur ther folding episodes. In conclusion, comparisons are noted between the ultimate fold pattern, the suggested evolution of these folds and H. Ramberg's experimentally produced orogenic structures. Introduction A survey of this particular area, situated north of the valley of Stjørdalen, east from Trondheim, was begun during the 1965 field-season and progressed during parts of the summers of 1966 and 1967 in conjunction with a mapping programme led by Statsgeolog Fr. Chr. Wolff further east in this same seg ment of the Central Norwegian Caledonides. Further geological mapping is contemplated, the aim being to eventually complete the 1 : 100,000 sheet 'Stjørdal' (rectangle 47 C). In view of the time factor involved in the comple tion of this work, and the renewed interest being devoted to the geological problems of the Trondheim region (Peacey 1964, Oftedahl 1964, Wolff 1964 and 1967, Torske 1965, Siedlecka 1967, Ramberg 1967), some notes on the tectonics of the Hegra area would seem appropriate at this stage. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Menighetsblad 6 - 2016 65.Årgang 2 Meldal Menighetsblad Dette Skjer I Menighetene Våre

Returadresse: Løkkenveien 2, 7336 Meldal Meldal B menighetsblad 6 - 2016 65.årgang 2 Meldal menighetsblad Dette skjer i menighetene våre: TACOKVELD Kirkestua, Meldal kirke fredag 25. november kl 18.00. ”O’ come let us adore Him” Arr: Normisjon Meldal kirke 11. desember kl 19.00 Etter overveldende tilbakemelding i fjor, blir det ny Løkken kirke konsert i Meldal kirke søndag 11. desember kl 19.00. søndag 27. november 11.00: Denne kvelden vil dere få gjenhør av noen Familiegudstjeneste med høydepunkter fra fjorårets konsert samt fl ere deltagelse av barna som har spennende innslag. deltatt i Lys Våken-overnatting Kom og bli med å fyll Meldal kirke, i kirka. Ved sokneprest Marita Hammervik Owen og så skaper vi ny juletrivsel sammen! diakon Magne Krogsgaard. Dagens takkoffer går til Det norske bibelselskap. Kirkekaffe etter gudstjenesten. LYSMESSE JULEVERKSTED Meldal kirke Meldal kirke søndag Årets juleverksted i Meldal kirke for alle 3., 4. og 27. november 19.00: 5. klassinger i Meldal sokn. Det blir også mulighet Lysmesse med deltagelse av til å være med på det fl otte julespillet for de som årets Meldalskonfi rmanter. ønsker det. Vi oppfordrer menighet og Oppstart torsdag 24. november kl 17.00-19.15. familie til å komme og fylle Videre datoer 1. og 8. desember samt ei samling kirka denne adventskvelden. etter jul. Ved sokneprest Marita Hammervik Owen og diakon Magne Krogsgaard. Dagens takkoffer går til Nidaros Løkken kirke misjonsprosjekt ”Lys til verden”. Vi inviterer 3., 4. og 5. klassinger i Løkken sokn til juleverksted i Løkken kirke tirsdag 6. desember Løkken kirke søndag 4. -

Kverneng/Kverning

Ancestors of Marit Larsdatter Kverneng (1 of 2) Parents Grandparents Great-Grandparents 2nd Great-Grandparents 4 Peder Estensen HOVIN Cont. p. 2 b: 1770 Hovin-Ekra, Horg, Norway m: 1798 in Horg Kirke, Melhus, Norway d: 1852 in Hovin-Ekra, Horg, Norway 20 Oluf Arntsen ROGNES 2 Lars Pedersen HOVIN b: 1698 Sørgarden Rognes, Støren, Norway b: 1808 Ekra Hovin, Horg, Norway m: 24 Jun 1723 in Støren Kirke, Støren, ST, m: 23 Jun 1842 in Røros, Sør-Trøndelag, Norway Norway d: 1767 in Gjerdet Løhre, Horg, Norway d: 1877 in Røros, Haltdalen, Norway 10 Steffen Olsen LØHRE b: 1724 Gjerdet Løhre, Horg, Norway m: 1757 in Horg Kirke, Melhus, Norway d: 1806 in Gjerdet Løhre, Horg, Norway Occupation: Farmer at Løhre 21 Kari LARSDATTER 5 Ingeborg Steffensdatter LØHRE b: 1696 Støren, Norway b: 1773 Gjerdet Løhre, Horg, Norway d: 1742 in Gjerdet Løhre, Horg, Norway d: 1864 11 Mali Haftorsdatter LØBERG 1 Marit Larsdatter KVERNENG b: 1737 aka: Marit KVERNING d: 1814 in Horg, Norway b: 01 May 1855 Kverneng, Røros, Haltdalen, Norway m: in America 6 Jens Jenssen BONDES d: in America aka: Jens Jenssen KVERNENG Spouse: Jon Iversen VOLD b: 1758 Røros, Haltdalen, Norway Emigration: 14 May 1880 m: Aft. 1808 Røros to Harpers Ferry, Iowa d: 1842 in Kverneng, Røros, Haltdalen, Norway Occupation: 09 Aug 1814 Became owner of Kverneng 3 Olava Jensdatter KVERNENG b: 1821 Røros, Haltdalen, Norway 28 Christian Andersen PRYTZ d: in America b: 1706 Emigration: 14 May 1880 d: 1783 Røros to Harpers Ferry, Iowa 14 Anders Christiansen PRYTZ b: 30 Jul 1740 Røros, Haltdalen, Norway d: 1815 in Røros, Haltdalen, Norway 7 Marit Andersdatter PRYTZ b: 1788 Prytz, Røros, Norway d: 1867 15 Kirsten JOHANNESDATTER © 7 April 2004 Linda K. -

The Raudfjellet Ophiolite Fragment, Central Norwegian Caledonides: Principal Lithological and Structural Features

LARS PETTER NILSSON,DAVID ROBERTS & DONALD M.RAMSAY NGU-BULL 445, 2005 - PAGE 101 The Raudfjellet ophiolite fragment, Central Norwegian Caledonides: principal lithological and structural features LARS PETTER NILSSON, DAVID ROBERTS & DONALD M.RAMSAY Nilsson, L.P., Roberts, D. & Ramsay, D.M. 2005: The Raudfjellet ophiolite fragment, Central Norwegian Caledonides: principal lithological and structural features. Norges geologiske undersøkelse Bulletin 445, 101–117. The Raudfjellet complex,Nord-Trøndelag,displays several of the features of a classical ophiolite pseudostratigraphy. At its base is a spectacular ultramafite mylonite. Elements represented include: (1) Ultramafic rocks, mostly dunite with minor harzburgitic and websteritic intrusions as well as sporadic dunite-chromitite cumulates. The dunite is interpreted to represent a single large body of cumulate dunite formed between the petrological and seismic Mohos. (2) A mafic unit consisting mostly of mafic cumulates and massive metagabbro, with alternating mafic and ultramafic cumulates near the base. (3) Possible dolerite dykes, in the upper part of the mafic block, with sheeted dykes observed in one small area. No tonalitic differentiates or basaltic lavas have been found at Raudfjellet. An unusual, hydrothermal alteration zone, up to 60 m thick, occurs at the interface between the ultramafic and mafic blocks. This zone consists of talc and listwaenite (magnesite-quartz rock). The ophiolite complex is unconformably overlain by a polymict conglomerate consisting mostly of mafic and -

Continental Collisions and the Creation of Ultrahigh-Pressure Terranes: Petrology and Thermochronology of Nappes in the Central Scandinavian Caledonides

Continental collisions and the creation of ultrahigh-pressure terranes: Petrology and thermochronology of nappes in the central Scandinavian Caledonides Bradley R. Hacker† Philip B. Gans‡ Department of Geological Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbara, California 93106-9630, USA ABSTRACT what extent is this paradigm correct? Conti- review the petrology and geochronology of nent-collision orogens form through a series of the major thrust sheets and then present new The formation of the vast Devonian stages involving (1) early arc ophiolite emplace- thermobarometry and thermochronology from ultrahigh-pressure terrane in the Western ment and continental passive margin contraction a key section inboard of the UHP terrane. We Gneiss Region of Norway was investigated by (typifi ed by the modern Australia-Banda arc conclude that the largest Norwegian UHP ter- determining the relationship between these collision) and subsequent relaxation (typifi ed by rane formed in the end stages of the continental ultrahigh-pressure rocks and the structur- Oman), (2) emplacement of oceanic sediments collision, following ophiolite emplacement and ally overlying oceanic and continental Köli and telescoping of the ophiolite-on-passive- passive margin subduction. Throughout, we use and Seve Nappes in the Trondelag-Jämtland margin assemblage, (3) emplacement of the the time scales of Tucker and McKerrow (1995) region. Thermobarometry and thermochro- upper-plate continent with its Andean-style arc, and Tucker et al. (1998). nology reveal that the oceanic Köli Nappes and (4) plateau formation and intracontinental reached peak conditions of 9–10 kbar and shortening (e.g., Tibet–Pamir). Can UHP ter- THE SCANDINAVIAN CALEDONIDES 550–650 °C prior to muscovite closure to ranes form during all of these stages, as implied Ar beginning at ca. -

Historisk Oversikt Over Endringer I Kommune- Og Fylkesinndelingen

99/13 Rapporter Reports Dag Juvkam Historisk oversikt over endringer i kommune- og fylkesinndelingen Statistisk sentralbyrå • Statistics Norway Oslo–Kongsvinger Rapporter I denne serien publiseres statistiske analyser, metode- og modellbeskrivelser fra de enkelte forsknings- og statistikkområder. Også resultater av ulike enkeltunder- søkelser publiseres her, oftest med utfyllende kommentarer og analyser. Reports This series contains statistical analyses and method and model descriptions from the different research and statistics areas. Results of various single surveys are also pub- lished here, usually with supplementary comments and analyses. © Statistisk sentralbyrå, mai 1999 Ved bruk av materiale fra denne publikasjonen, vennligst oppgi Statistisk sentralbyrå som kilde. ISBN 82-537-4684-9 ISSN 0806-2056 Standardtegn i tabeller Symbols in tables Symbol Tall kan ikke forekomme Category not applicable . Emnegruppe Oppgave mangler Data not available .. 00.90 Metoder, modeller, dokumentasjon Oppgave mangler foreløpig Data not yet available ... Tall kan ikke offentliggjøres Not for publication : Emneord Null Nil - Kommuneinndeling Mindre enn 0,5 Less than 0.5 of unit Fylkesinndeling av den brukte enheten employed 0 Kommunenummer Mindre enn 0,05 Less than 0.05 of unit Sammenslåing av den brukte enheten employed 0,0 Grensejusteringer Foreløpige tall Provisional or preliminary figure * Brudd i den loddrette serien Break in the homogeneity of a vertical series — Design: Enzo Finger Design Brudd i den vannrette serien Break in the homogeneity of a horizontal series | Trykk: Statistisk sentralbyrå Rettet siden forrige utgave Revised since the previous issue r Sammendrag Dag Juvkam Historisk oversikt over endringer i kommune- og fylkesinndelingen Rapporter 99/13 • Statistisk sentralbyrå 1999 Publikasjonen gir en samlet framstilling av endringer i kommuneinndelingen 1838 - 1998 og i fylkesinndelingen 1660 - 1998. -

20191212 Sak 84 Vedlegg Visitasprotokoll.Pdf

DEN NORSKE KIRKE Nidaros biskop Melhus menighetsråd Rådhuset 7224 MELHUS Dato: 04.12.2019 Vår ref: 18/02315-20 Deres ref: Visitasprotokoll for visitasen i Flå, Horg, Hølonda og Melhus sokn i Gauldal prosti 26. november - 1. desember 2019 Nidaros biskop vil takke for gode og inspirerende visitasdager i Flå, Horg, Hølonda og Melhus sokn. Vedlagt følger visitasprotokollen som består av følgende dokumenter: 1. Visitasforedrag ved biskop Herborg Finnset 2. Visitasprogram 3. Visitasmeldinger fra Flå, Horg, Hølonda og Melhus sokn. 4. Rapporter fra Melhus kirkelige fellesråd 5. Befaringsrapport fra prosten 6. Oversikt over ansatte og rådsmedlemmer Jeg ber om at prosten innkaller rådsmedlemmer og ansatte til et oppfølgingsmøte innen 1. juni 2019. De ulike instanser bes gjennomgå protokollen som forberedelse til oppfølgingsmøtet. Kirkefagsjef Inge Torset vil representere Nidaros biskop på oppfølgingsmøtet. Jeg ber kirkevergen formidle protokollen videre til rådsmedlemmer og øvrige ansatte. Protokollen må gjerne formidles til andre instanser som kunne ha nytte av den. Med vennlig hilsen Herborg Finnset biskop Steinar Skomedal stiftsdirektør Dokumentet er elektronisk godkjent og har derfor ingen signatur. Vedlegg: 01 Menighetsberetning bispevisitas 2019 m kort innføring om melhus kommune – Kopi – Kopi 02 Visitas19 Beretning om Hølonda menighet (1) – Kopi – Kopi 03 Til bispevisitasen i Melhus 26 - Rapport Horg 3 utkast - endelig – Kopi – Kopi Postadresse: E-post: [email protected] Telefon: +47 73 53 91 00 Saksbehandler Erkebispegården Web: kirken.no/nidaros -

Gamle Hus Da Og Nå

GAMLE HUS DA OG NÅ Dal og Rognbrøt Foto KMK 2003 Status for SEFRAK-registrerte bygninger Melhus kommune Sør-Trøndelag fylke 2003 Trykt: Allkopi, Oslo 2007 Forord Kulturminnekompaniet foretok år 2003 på oppdrag fra Riksantikvaren en kontrollregistrering av ca 3000 bygninger i kommunene Melhus, Snåsa, Flora og Vega. Undersøkelsen bygger på en landsomfattende registrering av hus bygd før 1900 kalt SEFRAK- registreringen. De innsamlete dataene danner grunnlaget for databasen Nasjonalt bygningsregister som ble åpnet i 2000. Undersøkelsen ble gjort som et ledd i Riksantikvarens overvåkingsprogram av SEFRAK-registrerte hus i et representativt antall kommuner. Ved hjelp av periodiske kontrollregistreringer er målet å få informasjon om desimeringstakt og endringer på bygg eldre enn 1900. Kontrollregistreringen knytter seg til nasjonalt resultatmål 1: ”Det årlige tapet av kulturminner og kulturmiljøer som følge av fjerning, ødeleggelse eller forfall, skal minimeres, og skal innen år 2020 ikke overstige 0,5 % årlig”. Systematisk kontrollregistrering ble i år 2000 foretatt i kommunene Nord-Aurdal, Gjerstad, Fræna og Kautokeino, 2001 i Tromsø og 2002 i Sandnes, Eidskog, Skjåk og Saltdal. Tidligere var det gjort spredte undersøkelser i presskommuner i Osloregionen – Nittedal, Lier og Ullensaker. Disse viste et gjennomsnittlig årlig tap på 1 % for hus eldre enn 1900. Satt på spissen vil dette si at om 80 år ville alle hus eldre enn 1900 være borte. Rapporten er skrevet av Kulturminnekompaniet. Rapportformen bygger på Nittedalrapporten, men er omarbeidet i samarbeid med Riksantikvaren, ved Gro Wester i 2000, fra 2001 Anke Loska. September 2006 Unni Broe og Solrun Skogstad Innhold 0 SAMMENDRAG............................................................................................................. 7 0.1 Nøkkeltall Melhus................................................................................................................. 7 0.2 Kvantitative forandringer ...................................................................................................