Impacting Student Learning and Growth in Utah Schools Annual Evaluation Report (2019-2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Juan School District

Announcement of Position Superintendent of Schools SAN JUAN SCHOOL DISTRICT Mission Statement The mission of the San Juan School District is to unite parents, students, educators, and communities to enable all students to become empowered, literate, well-adjusted, and productive citizens. Superintendent Announcement Dr. Douglas E. Wright has served as Superintendent for the past 14 years. The San Juan School Board is committed to finding the very best candidate to fill this position and strongly urges eligible candidates to apply. The San Juan School District is vast, diverse, and prepared for a great future of student achievement and excellence. The District has a general fund balance in excess of $10 million and carries no debt. In the past the ten years, the District has completed nearly $40 million in capital projects after adopting a pay-as-you-go Capital Outlay plan. This has allowed for extensive remodeling of the major high schools and construction of two new elementary schools. Additional construction and renovations are planned, with the debt- free funding mechanism in place. An innovative academic program, based on collaboration and use of data, has resulted in enhanced and improved academic performance of students District wide. A modern and extensive technology infrastructure is in place to meet the needs of the digital age students. 1 Salary and Benefits Salary will be commensurate with experience and be comparable to salaries of superintendents of similar sized districts in the State of Utah. Application Requirements Qualified candidates should submit a formal application which includes: • Personal philosophy of education including a vision statement addressing what you feel are the essential skills and characteristics of an effective superintendent. -

2019-2020 Title I Schools

Utah Title I Schools 2019-2020 LEA School Grade Number District Name Number Building Name Span TA SW NEW Address City Zip 1 Alpine School District 107 Bonneville Elementary PK-6 SW 1245 North 800 West Orem 84057 1 Alpine School District 116 Central Elementary PK-6 SW 95 North 400 East Pleasant Grove 84062 1 Alpine School District 118 Cherry Hill Elementary PK-6 SW 250 East 1650 South Orem 84097 1 Alpine School District 128 Geneva Elementary PK-6 SW 665 West 400 North Orem 84057 1 Alpine School District 132 Greenwood Elementary PK-6 SW 50 East 200 South American Fork 84003 1 Alpine School District 161 Mount Mahogany Elementary PK-6 TA 618 N 1300 W Pleasant Grove 84062 1 Alpine School District 414 Orem Junior High School 7-9 TA 765 North 600 West Orem 84057 1 Alpine School District 168 Sharon Elementary PK-6 SW 525 North 400 East Orem 84097 1 Alpine School District 174 Suncrest Elementary PK-6 SW 668 West 150 North Orem 84057 1 Alpine School District 178 Westmore Elementary PK-6 SW 1150 South Main Orem 84058 1 Alpine School District 182 Windsor Elementary PK-6 SW 1315 North Main Orem 84057 2 Beaver School District 104 Belknap Elementary K-6 SW 30 West 300 North, P.O. Box 686 Beaver 84713 2 Beaver School District 108 Milford Elementary K-6 SW 450 South 700 West, P.O. Box 309 Milford 84751 2 Beaver School District 112 Minersville Elementary K-6 SW 450 South 200 West, P.O. Box 189 Minersville 84752 3 Box Elder School District 125 Discovery Elementary K-4 SW 810 North 500 West Brigham City 84302 3 Box Elder School District 150 Lake View Elementary -

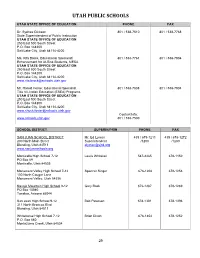

Utah Public Schools

UTAH PUBLIC SCHOOLS UTAH STATE OFFICE OF EDUCATION PHONE FAX Dr. Sydnee Dickson 801 / 538-7510 801 / 538-7768 State Superintendent of Public Instruction UTAH STATE OFFICE OF EDUCATION 250 East 500 South Street P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200 Ms. Rita Brock, Educational Specialist/ 801 / 538-7761 801 / 538-7804 Enhancement for At-Risk Students, MESA UTAH STATE OFFICE OF EDUCATION 250 East 500 South Street P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200 [email protected] Mr. Harold Foster, Educational Specialist 801 / 538-7838 801 / 538-7804 Title VII-Indian Education (ESEA) Programs UTAH STATE OFFICE OF EDUCATION 250 East 500 South Street P.O. Box 144200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-4200 [email protected] Contact Info: www.schools.utah.gov 801 / 538-7530 SCHOOL DISTRICT SUPERIN/PRIN PHONE FAX SAN JUAN SCHOOL DISTRICT Mr. Ed Lyman 435 / 678-1211 435 / 678-1272 200 North Main Street Superintendent /1200 /1280 Blanding, Utah 84511 [email protected] www.sanjuanschools.org Monticello High School 7-12 Lewis Whitaker 587-2465 678-1150 PO Box 69 Monticello, Utah 84535 Monument Valley High School 7-12 Spencer Singer 678-1208 678-1258 100 North Cougar Lane Monument Valley, Utah 84536 Navajo Mountain High School 9-12 Gary Rock 672-1287 678-1289 PO Box 10040 Tonalea, Arizona 86044 San Juan High School 9-12 Bob Peterson 678-1301 678-1396 311 North Broncos Blvd. Blanding, Utah 84511 Whitehorse High School 7-12 Brian Dixon 678-1854 678-1252 P.O. -

SOC Directory

SOC Directory We gain strength, and courage, and confidence by each experience in which we really stop to look fear in the face ... we must do that which we think we cannot. Eleanor Roosevelt Participating Agencies Division Child and Family Services Division Juvenile Justice Services Division of Workforce Services San Juan Counseling San Juan School District Seventh District Juvenile Court Page 2 EMERGENCIES Life Threatening .................................................................. 9-1-1 Crisis/Suicide Prevention………………………..….678-2992 After hours - page or call 9-1-1 and ask for an on call mental health worker..1-435-678-1757 Poison Control .................................................... 1-800-222-1222 ADULT & CHILD ABUSE/NEGLECT Adult Protective Services (APS) (Reporting)….1-800-371-7897 Moab Office ...........................................................(435) 259-3729 Division of Child and Family Services (DCFS) Child Protective Services (CPS) (Reporting) ....................................................................... 678-1491 Ambulance Services (Emergency Only) ............. 1-800-332- 1911 Non-Emergency .............................................................. 678-2034 Emergency Management Office/Fire...........................587-3225 Fire Department (Blanding) ........................................................................ 678-2837 San Juan County Systems of Care Page 3 Directory Table of Contents Table of Contents Mission and Values Statements 4 Introduction to SOC 5 Division of Child and Family Services 6 Division of Juvenile Justice Services 7 Division of Workforce Services 8 Seventh District Juvenile Court 9 San Juan Counseling 10-11 San Juan School District 12-13 Health Care 14-15 Tribal Services 16-17 Law Enforcement 18 Domestic Violence 19 Alyn Mitchell Chairman Travis Pehrson Coordinator We gain strength, and courage, and confidence by each experience in which we really stop to look fear in the face ... we must do that which we think we cannot. -

Safe Schools Policies

SAFE SCHOOLS POLICIES www.sjsd.org San Juan School District is committed to maintaining safe environments for all students and staff. In today's world, schools must enforce safe schools' policies diligently. We encourage parents and students to be familiar with these expectations in order to avoid situations that warrant unpleasant or serious consequences. If you have questions, please contact your local school administrator or district administration. Superintendent Douglas E. Wright—678 1211 Anthony Done, Special Education Director—678 1222 Clayton Holt, Business Administrator—678 1234 Lynnette Johnson, Student Services Director—678 1227 Kit Mantz, Human Resources Director—678 1270 Ron Nielson, Elementary Supervisor—678 1213 Chas DeWitt, Secondary Supervisor—678 1288 SCHOOL INFORMATION A. R. L. Middle School Monticello, Utah 84535 Principal Kim Bailey PH: (435) 587-2465 or 587-2150 [email protected] PH: (435) 678-1130 FX: (435) Bill Sivert, Assistant Principal 678-1150 [email protected] Monument Valley High Mary Ann Pugh, Counselor Principal Patricia A. Seltzer [email protected] [email protected] 535 North 100 East Connie Williams, Assistant Principal Blanding, Utah 84511 [email protected] PH: (435) 678-1398 FX:(435) 678-1399 Janae Herrera, Counselor Blanding Elem School [email protected] Principal Mark Burge P. O. Box 360008 [email protected] Monument Valley, Utah 84536 Shelby Eldredge, Counselor PH: (435) 727-3204 PH: (435) [email protected] 678-1208 302 South 100 West FX: (435) 678-1258 Blanding, Utah 84511 Navajo Mountain High PH: (435) 678-1872 FX: (435) Principal Orlo Knight 678-1877 [email protected] Bluff Elementary School Janae Herrera, Counselor Principal Barbara Silversmith [email protected] [email protected] P. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of UTAH CENTRAL DIVISION NAVAJO NATION, a Federally Recognized Indian Tribe

Case 2:12-cv-00039-RJS-DBP Document 185 Filed 08/28/15 Page 1 of 107 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH CENTRAL DIVISION NAVAJO NATION, a federally recognized Indian tribe, et al., Civil No. 2:12-cv-00039-RS Plaintiffs, v. Judge Robert J. Shelby Magistrate Judge Dustin B. Pead SAN JUAN COUNTY, a Utah governmental subdivision, Defendant. EXPERT WITNESS REPORT OF DR. DONNA DEYHLE The Educational Experiences of American Indians in San Juan, Utah, County Schools Research Results Summary The examination of the historical relationships between Indian and white communities in San Juan County, Utah, revealed two clear patterns: 1). Disparities in access to schools between whites and Indians and 2). Historical patterns of resistance to providing schools for Indian students. Contemporary educational practices in San Juan School District also show disparities in San Juan School District’s efforts to educate American Indians, such as: 1). Pushing out academically challenged American Indian students into dropping out of schools; 2). 1 Case 2:12-cv-00039-RJS-DBP Document 185 Filed 08/28/15 Page 2 of 107 Disproportionate punishing disciplinary actions against American Indian students; 3). Vocational tracking of American Indian students; 3). Limited access to educational services; 4). Remedial curriculum; 5).Remedial reading courses. 6). Racial conflict in classrooms and school. 7). The lack of academic achievement impacts civil participation, including voting. These practices by educators and administrators in San Juan School district disadvantages American Indian students and, in turn, depresses their civic participation in San Juan County. Tension between Indian and white populations in San Juan County, and racism and discrimination were recurring themes that emerged in my interviews over the past 30 years with white and Indian peoples. -

American Marten Found in the La Sals San Juan Recordadapts To

San Juan Record HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER FOR SAN JUAN COUNTY, UTAH SINCE 1915 Volume 104 Number 49 50 cents September 11, 2019 San Juan Record adapts to changes, expands to meet reader needs The San Juan Record is paper,” said Boyle. in the process of develop- The paper will be print- ing a “2020 Vision” as the ed in several smaller sec- information industry con- tions. tinues to grow and trans- In addition, the San form. Juan Record website is This vision will result in the process of being re- in a few changes in com- vamped. The new web- ing weeks. “Our reader- site, which will be intro- ship has never been larg- duced in coming weeks, er,” said San Juan Record will feature increased ca- Publisher Bill Boyle. “The pabilities. challenge is making sure “Beautiful color pho- we change to meet the de- tography is an important veloping needs of our read- part of the San Juan Re- ers.” cord,” said Boyle. “The The Monticello Homecoming Royalty reigned over a full week of activities in the past week. The homecoming royalty includes For the past ten years, new website will highlight Miss Congeniality Macy Badger, Queen Shelbie Musselman, First Attendant Makayla Sheeran, and Second Attendant Morgan the San Juan Record has that photography, much Maloy. Robin Garner photo been printed at the Medi- of which comes from our aOne press in West Val- readers. ley City. That relationship “In addition, the new will end with this issue of website will have in- the newspaper. creased capabilities for Judge rejects SUWA motion in public lands case Beginning next week, audio and video.” With a scathing rebuke, decision on the case will be before the court.” ney in a previous hearing, the San Juan Record will The changes will also in- a federal judge rejected have far-reaching impli- SUWA had previously “I know the court is com- be printed at the Gannett clude an increased pres- a motion by the South- cations in San Juan Coun- been given an increased mitted to that (a timely Press in Farmington, NM. -

Technical Report La Sal District Project

TECHNICAL REPORT ON LA SAL DISTRICT PROJECT (Including the Pandora, Beaver, and Energy Queen Projects) San Juan County, Utah, U.S.A. Prepared for Energy Fuels Inc. In Compliance with Canadian National Instrument 43-101 “Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects” Prepared by Douglas C. Peters, Certified Professional Geologist NI 43-101 Qualified Person Peters Geosciences Golden, Colorado Report Date: March 25, 2014 La Sal District Project NI43-101 Technical Report i Peters Geosciences March 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents 1.0 Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Land and Facility Status ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 History .................................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Geology and Mineralization ................................................................................. 3 1.4 Mineral Resources ................................................................................................ 4 1.5 Conclusions .......................................................................................................... 5 1.6 Recommendations ................................................................................................ 5 2.0 Introduction and Terms of Reference ..................................................................... 4 3.0 Reliance on Other Experts ..................................................................................... -

Expert Witness Report by Dr. Daniel Mccool in the Case Of: Navajo Nation V. San Juan County, UT Case. No. 2:12-Cv-00039-RS August 18, 2015

Case 2:12-cv-00039-RJS-DBP Document 181 Filed 08/19/15 Page 1 of 247 Expert Witness Report by Dr. Daniel McCool in the case of: Navajo Nation v. San Juan County, UT Case. No. 2:12-cv-00039-RS August 18, 2015 [please print in color] OUTLINE OF THE REPORT I. INTRODUCTION 1. Qualifications 3 2. Purpose of Analysis/Research Questions 4 3. Qualitative Methodology 6 II. CONTEXT 1. Historical Discrimination and Sequence of Events 9 A. National/Utah 9 B. Regional/Reservation 13 C. San Juan County 27 a. Opposition to Extending the Navajo Reservation 35 b. Opposition to a Ute Reservation 40 2. Discrimination 42 A. The Context of Discrimination 43 B. Discrimination in San Juan County 46 C. The Language of Discrimination 55 3. The Larger Socio-economic Context 59 A. Employment and Poverty 59 B. Religion 71 III. ELECTIONS AND POLITICAL COHESION 1. Geographical Compactness of the Reservation 80 2. Bloc Voting and Political Cohesion 82 3. Factors That Dilute the Ability of Indians to Participate 104 A. No Right to Vote 104 B. Polarized Political Environment 114 a. Use of Racial Appeals in Elections 129 Case 2:12-cv-00039-RJS-DBP Document 181 Filed 08/19/15 Page 2 of 247 2 b. Contemporary Statements of County Officials 130 c. Hostility over Natural Resources 133 > Uranium 135 > Oil 138 > Utah Navajo Trust Fund 140 > Coal 146 > Public Land 148 C. Electoral Procedures and Vote Dilution 154 a. Low Turnout 154 b. Inaccurate Census Counts 157 c. Unusually Large Election Districts 159 > County Precincts 159 > School Districts 160 d. -

Grant Sample: San Juan School District

Utah State Board of Education Utah K-12 Computer Science Initiative San Juan School District 4-year Full Grant Application TEAM: Computer Science Leadership LEA Name Title Name Email Phone LEA Computer Science Lead Kit Mantz [email protected] (435) 678-1318 Superintendent Ron Nielson [email protected] (435) 678-1211 CTE Director Kit Mantz [email protected] (435) 678-1318 K-6 Curriculum Director Julie Holt [email protected] (435) 678-1213 7-12 Curriculum Director Christy Fitzgerald [email protected] (435) 678-1309 Technology Director Aaron Brewer [email protected] (435) 678-1217 Elementary Principal Jay Porter [email protected] (435) 678-1870 Elementary Principal Mike Tuckfield [email protected] (435) 678-1285 Secondary A/Principal Devon Gosney [email protected] (435) 678-1254 Business Administrator Kyle Hosler [email protected] (435) 678-1234 IT/Educ. Technology Specialist David Brown [email protected] (435) 678-1221 SESC Coordinator Theresa Wilson [email protected] (435) 650-2283 Computer Science High School Ramsey Teacher Leader Seweingyawma [email protected] (435) 678-1209 ADA Compliant: December 2020 High School Teacher Leader/PD Coordinator Jamie Carling [email protected] (435) 678-1301 Middle School Teacher Leader David Hale [email protected] (435) 678-1100 Middle School Teacher Leader Tina Crofts [email protected] (435) 678-1100 Elemen School Teacher Leader Patricia Helquist [email protected] (435) 678-1871 School Board Member Steve Black [email protected] (435) 485-0298 VISION: Abstract for K-12 Computer Science Plan The San Juan School District understands that Computer Science (CS) is becoming a very important component of student learning and engagement and the District is looking forward to implementing its detailed CS strategy to integrate the K-12 Computer Science standards for all students in every grade and to offer important CS classes and CS pathways in grades 7-12. -

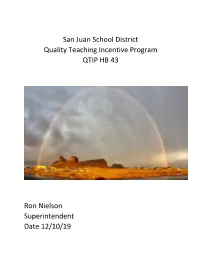

San Juan School District Quality Teaching Incentive Program QTIP HB 43

San Juan School District Quality Teaching Incentive Program QTIP HB 43 Ron Nielson Superintendent Date 12/10/19 SJSD Quality Teaching Incentive Program QTIP Objective of Program: To foster in all schools a collaborative faculty, rich in experience and pedagogy skills, and fully prepared to successfully deliver high quality instruction in all classrooms. School Number of Year One Year two Year Retention Positions Three Numbers approved by board Elementary Bluff Elementary 2 2 2 2 2/2 Montezuma 4 0 4 4 NA Creek Elementary Tsebii’nidzisgai 4 3 4 4 3/4 Elementary Secondary Navajo Mountain 1 1 1 1 1/1 High Monument Valley 5 1 2 3 1/2 High Whitehorse High 5 0 1 1 1/1 Totals 21 7 14 15 8/10 Grant Objectives: 1. Increase Efforts to Attract Quality Candidates to teach in our six southern Schools. a. Certified elementary teachers teaching in the three southern elementary schools receive $1,000 minimum signing bonus. b. Certified math and science teachers in secondary schools receive $2,500 minimum signing bonus. c. Certified LA teachers in secondary schools receive $1000 minimum signing bonus. d. Certified critical area teachers can receive a relocation stipend up to $500 dollars. e. Certified critical area teachers can receive a visitation stipend of up to $250 to come and visit the school and community. 2. Grow our own teacher Pool a. This past Fall, SJSD hired four teachers out of the first local cohort graduating from the USU Rural Southeastern Teaching Education Project. b. SJSD is committed to work closely with USU to ensure future success of this project. -

RAISE the BAR, EARN YOUR STAR! We Want 100% of Our Member Schools to 4

Utah High School Activities Association RaiseSportsmanship the Matters! Bar UPDATE December 2010 - Volume 24, Number 2 Alignment Approved for 2011-13 n November 18, 2010, the Board of Trustees (BOT) which is the policy Omaking body of the Utah High School Activities Association, passed the final consideration of regions under the new alignment for 2011-13. The decision came the day after a public hearing was held to provide the BOT with feedback from districts, schools and communities on the placement of member schools into regions. In addition to the hearings, the UHSAA Board of Trustees received numerous emails over the past few months regarding the new procedure for the realignment of member schools. The following are the number of schools and regions in each classification for the 2011-2013 alignment period: Off the CUFF 5A: 24 schools (four regions of six schools) Thoughts from UHSAA Executive Director Rob Cuff 4A: 26 schools (three regions of six, one region of eight schools) Southeastern Utah is Canyon Country 3A: 26 schools (two regions of seven schools, two regions of six schools) Southeastern Utah is known for its sweeping views, stunning red rock forma- 2A: 20 schools (four regions of five schools) tions, desert mystery, mountain grandeur 1A: 36 schools (three regions of six schools, two regions of nine schools) and intimate canyons. Earlier this year, the BOT adopted a new procedure intended to make the However, when it comes to the Utah High process more objective, efficient, timely and equitable for post-season School Activities Association, South- bracketing. The new procedure provides for the realignment of schools every eastern Utah is known more for its seven two years.