Between Mottile and Ambiloxi: Cordwainer Smith As a Southern Writer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rediscovery of Man Free Download

THE REDISCOVERY OF MAN FREE DOWNLOAD Cordwainer Smith | 400 pages | 29 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575094246 | English | London, United Kingdom The Rediscovery of Man Sure, I can say it has pages of acclaimed stories—every short story that Cordwainer Smith ever wrote. After defeat, after disappointment, after ruin and reconstruction, mankind had leapt among the stars. The Rediscovery of Man Rediscovery of Man, by Cordwainer Smith. The majority of these stories take place 14, yeas into the future, and The Rediscovery of Man this day, present a The Rediscovery of Man worldview, and an astounding examination of human nature. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. This brilliant collection, often cited as the first of its kind, explores fundamental questions about ourselves and our treatment of the universe and other beings around us and ultimately what it means to be human. Cordwainer Smith is a writer like none other. These stories were written in the late 50s, early 60s, and are so intelligent and forward thinking, I'm still stunned. Underpeople do all the hard work, police is made up of robots and telepathic mind control checks that everybody is thinking happy thoughts, or they are sent for re-education. A Cordwainer Smith Panel Discussion. That said, when I said last time that I was relieved that Tiptree's radical feminism never crossed the line into open transphobia, a finger on the monkey's paw curled up and delivered me Smith's "The Tranny Menace from Beyond the Stars" "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal," about which I have absolutely nothing positive to say. -

Steam Engine Time 5

Steam Engine T ime PRIEST’S ‘THE SEPARATION’ MEMOS FROM NORSTRILIA CENSORSHIP IN AUSTRALIA POLITICS AND SF Harry Hennessey Buerkett James Doig Paul Kincaid Gillian Polack Eric S. Raymond Milan Smiljkovic Janine Stinson Issue 5 September 2006 Steam Engine T ime 5 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 5, September 2006 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). Members fwa. First edition is in .PDF file format from eFanzines.com or from either of our email addresses. Print edition available for The Usual (letters or substantial emails of comment, artistic contributions, articles, reviews, traded publications or review copies) or subscriptions (Australia: $40 for 5, cheques to ‘Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd’; Overseas: $US30 or £15 for 5, or equivalent, airmail; please send folding money, not cheques). Printed by Copy Place, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. The print edition is made possible by a generous financial donation. Graphics Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos of (p. 5) Christopher Priest, by Ian Maule; (p. 24) Roger Dard, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 25) Roger Dard fanzine contributions, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 32) Nigel Burwood, Martin Stone and Bill Blackbeard, by John Baxter; (p. 39) David Boutland. 3 EDITORIAL 1: 32 Letters of comment ‘Dream your dreams’: A meditation on Babylon 5 John Baxter Janine Stinson Rosaleen Love Steve Jeffery 4 EDITORIAL 2 E. B. Frohvet Bruce Gillespie Steve Sneyd Sydney J. -

Single-Gendered Worlds in Science Fiction: Better for Whom? Victor Grech with Clare Thake-Vasallo and Ivan Callus

VECTOR 269 – SPRING 2012 Single-gendered Worlds in Science Fiction: Better for Whom? Victor Grech with Clare Thake-Vasallo and Ivan Callus n excess of one gender is a regular and worlds are commoner than men-only worlds is that a problematic trope in SF, instantly removing any number of writers have speculated whether a world Apotential tension between the two sexes while constructed on strict feminist principles might be utopian simultaneously generating new concerns. While female- rather than dystopian, and ‘for many of these writers, only societies are common, male-only societies are rarer. such a world was imaginable only in terms of sexual This is partly a true biological obstacle because the female separatism; for others, it involved reinventing female and body is capable of bringing a baby forth into the world male identities and interactions’.2 after fertilization, or even without fertilization, so that a These issues have been ably reviewed in Brian prospective author’s only stumbling block to accounting Attebery’s Decoding Gender in Science Fiction (2002), in for the society’s potential longevity. For example, which he observes that ‘it’s impossible in real life to to gynogenesis is a particular type of parthenogenesis isolate the sexes thoroughly enough to demonstrate […] whereby animals that reproduce by this method can absolutes of feminine or masculine behavior’,3 whereas only reproduce that way. These species, such as the ‘within science-fiction, separation by gender has been the salamanders of genus Ambystoma, consist solely of basis of a fascinating series of thought experiments’.4 females which does, occasionally, have sexual contact Intriguingly, Attebery poses the question that a single- with males of a closely related species but the sperm gendered society is ‘better for whom’?5 from these males is not used to fertilise ova. -

VECTOR 58 Is Edited by Bob Parkinson, 106 Ingram Avenue, Aylesbury, Bucks

NO 58 JOHN CROMPTON on CORDWAINER SMITH VECTOR N958 VECTORED 2 C'THEME AND M'STYLE IN CORWAINER SMITH John Crompton U CORDWAINER SMITH: A BRIEF PROFILE Bob Parkinson 12 ANDRE NORTON’S WITCH WORLD FANTASIES Fred Oliphant U COMMUNICATION AND ORGANIZATION Keith Freeman 16 BOOKS 17 cover: Judy Evans & Bob Parkinson interior illustrations (delivered at very short notice): David Rowe for "A Planet Named Shayol" VECTOR 58 is edited by Bob Parkinson, 106 Ingram Avenue, Aylesbury, Bucks. Production Manager: Derek J Rolls Advertising Manager: Roger G. Peyton, 131 Gillhurst Road, Birmingham 1 ?• Published by the British Science Fiction Association, Executive Secretary: Mrs A. E. Walton, 25 Yewdale Crescent, Coventry CV2 2FF. JULY 1971 ftrice: 25 p. BETWEEN TWO WORLDS vectored Among my intentions for this column, it has Characteristically, the situation that Mailer found been my aim with each issue to write of one was ambiguous Oriana Fallaci, who had explored much book that has caught my attention in the months the same route earlier in her If The Sun Dies, wrote a immediately before Thus far we have had one book of conversion literature along side St Augustine's sf book written by a "mainstream" author and a Confessions or William Burrough's Nova Express But fantasy written by a non-sf author This time Mailer, sandwiching Apollo 11 between the failure of round I want to discuss a non-sf, non-fiction his mayoraiity campaign in New York and the break-up book written by someone outside the field entir- of his marriage, winds up finding that he is -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90d94068 Author Evans, Taylor Scott Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Taylor Scott Evans December 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Mark Minch-de Leon Mr. John Jennings, MFA Copyright by Taylor Scott Evans 2018 The Dissertation of Taylor Scott Evans is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Whenever I was struck with a particularly bad case of “You Should Be Writing,” I would imagine the acknowledgements section as a kind of sweet reward, a place where I can finally thank all the people who made every part of this project possible. Then I tried to write it. Turns out this isn’t a reward so much as my own personal Good Place torture, full of desire to acknowledge and yet bereft of the words to do justice to the task. Pride of place must go to Sherryl Vint, the committee member who lived, as it were. She has stuck through this project from the very beginning as other members came and went, providing invaluable feedback, advice, and provocation in ways it is impossible to cite or fully understand. -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R. -

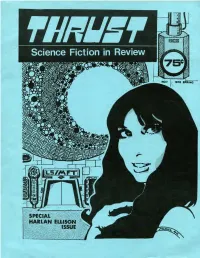

THR 1976 1.Pdf

creative writers and artists appear in rounter tfjrusit COLLEGE PARK, MD. 20740 50C thrust contents Cover by Steve Hauk.....page 1 Contents page (art by Richard Bryant).page 3 Editorial by Doug Fratz (art by Steve Hauk).page 4 THRUST INTERVIEW: HARLAN ELLISON by Dave Bischoff and Chris Lampton (axt by Steve Hauk)...page 5 Alienated Critic by Doug Fratz (art by Don Dagenais).page 12 Conventions (art by Jim Rehak).page 13 Centerspread art by Richard Bryant.page 14 Harlan Ellison vs. The Spawning Bischii by David F. Bischoff.page 16 Book Reviews by Chris Lampton, Linda Isaacs, Dave Bischoff, Melanie Desmond and Doug Fratz (art by Richard Bryant and Dennis Bailey ).page 21 ADVERTISING: Counter-Thrust Fantasy Magazine...page 2 The Nostalgia Journal.....page 27 Crazy A1 ’ s C omix and Nostalgia Shop....page 28 staff Editor-in-Chief: Computer Layout: LEE MOORE and NATALIE PAYMER Doug Fratz Art Director: Managing Editor: STEVE HAUK Editorial Assistants: Dennis Bailey RON WATSON and BARBARA GOLDFARB Staff Writers: Associate Editor: DAVE BISCHOFF Melanie Desmond EE SEE? EDITORIAL by Doug Fratz I created THRUST SCIENCE FICTION more than find it incredibly interesting reading it over three years ago, and edited and published five for the tenth or twelveth time. Ted Cogswell issues, between February 1973 and May 1974, should take special note. completely from my own funds. When I received In addition, THRUST will have a sister my degree from the University of Maryland, I magazine of sorts, COUNTER-THRUST, to be pub¬ decided to turn THRUST over to other editors. lished yearly, once each summer. -

Behind the Jet-Propelled Couch: Cordwainer Smith and Kirk Allen

Behind the Jet-Propelled Couch: Cordwainer Smith and Kirk Allen Alan C. Elms [Originally published in the New York Review of Science Fiction, May 2002] In 1978 I began to pursue the question of whether Paul Linebarger, aka Cordwainer Smith, had been the patient in “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” a psychoanalytic case history written by Robert Lindner. Over the past quarter-century I’ve accumulated more information and ideas on that question than I can fully present here. Instead I’ll use the format of a FAQ – a list of “frequently asked questions” and fairly brief answers. 1.) Why are you doing this? a) As a follow-up to one of the most famous case histories ever published. Robert Lindner’s book, The Fifty-Minute Hour, has sold several million copies since its first publication in 1955 and has remained almost constantly in print. The book’s most fascinating case, “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” has been reprinted in magazines and anthologies, has been dramatized on live TV, has repeatedly been optioned for a feature- length film, and even provided the basis for a Stephen Sondheim musical that (like all those potential film versions) was never completed. b) The case study has been of special interest to sf fans ever since its early reprinting in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Its protagonist, a patient called Kirk Allen, experienced what struck many fans as the ideal psychosis: he spontaneously found himself living a heroic life as “Lord of a planet in an interplanetary empire,” far in the future (Fifty-Minute Hour, 250). -

Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger Papers, 1922-1967

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9s200760 No online items Register of the Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger Papers, 1922-1967 Processed by Grace M. Hawes; machine-readable finding aid created by Michael C. Conkin Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 1998 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Paul Myron 82115 1 Anthony Linebarger Papers, 1922-1967 Register of the Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger Papers, 1922-1967 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Processed by: Grace M. Hawes Date Completed: 1985 Encoded by: Michael C. Conkin © 1998 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger Papers, Date (inclusive): 1922-1967 Collection Number: 82115 Creator: Linebarger, Paul Myron Anthony, 1913-1966 Collection Size: (33 manuscript boxes, 7 microfilm reels, 1 album box, 2 envelopes (15 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Diaries, correspondence, speeches and writings, printed matter, and photographs, relating to political conditions in China and elsewhere in the Far East, and to psychological warfare during and after World War II. Includes microfilm of P. M. A. Linebarger papers at the Hitotsubashi University Library, Tokyo. Language: English. Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. To listen to sound recordings or to view videos or films during your visit, please contact the Archives at least two working days before your arrival. -

Panel About Isaac Asimov

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Frank White and Robert Godwin July 2018 Frank White is best known for his writing of the 1987 book The Overview Effect — Space Exploration and Human Evolution, in which he coined the term “the Overview Effect.” The book has now gone through three editions and Frank is preparing the fourth. He has appeared on The Space Show hosted by Dr. David Livingston, and has given numerous speeches at space events. He also co-authored "Think About Space: Where Have We Been and Where Are We Going?" and "March of the Millennia," with Isaac Asimov. Robert Godwin is also a super-fan of Asimov. He owns over 400 of his books. He owns every single SF book he wrote, including first editions of Foundation and Nightfall which Asimov signed for him many years ago. He also has almost all of his early Pulp appearances back to the 1940s. Sadly, when Asimov died, Godwin's letter of condolence was the very first one published in Asimov's SF Magazine. Seth A. Milman: Because of ambiguity in human language, there is almost always a disconnect between the intended meaning of a rule and the interpretation of a rule. This is evident in Asimov's three rules of robotics. The rules are written using high-level, ambiguous language. They are moralistic and idealistic rather than formulaic. But they are interpreted very strictly by the robots. Did Asimov intentionally design the laws of robotics this way at the outset, to use the ambiguity between the intended meaning of the rule and the rigid interpretation of the rule as a thematic/plot device? Or did his themes surrounding these rules develop after he came up with the rules? Frank White: I am not sure of the answer, but I think it is a bit of both. -

An Homage to Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (1913 – 1966) Writing As Cordwainer Smith

An homage to Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (1913 – 1966) writing as Cordwainer Smith Paul Linebarger’s father was a legal adviser to the Republic of China and a close personal friend of the founder of modern China, Dr Sun Yat-sen, who became young Paul’s godfather. His father moved the family to France and then Germany while Sun Yat-sen was struggling against contentious warlords in China. As a result, Linebarger had unparalleled cross-cultural childhood experiences. By adulthood he had become fluent in six languages and. at age 23 received a PhD in Political Science from Johns Hopkins University. He was Professor of Political Science at Duke University from 1937 to 1946 where he produced highly regarded works on Far Eastern Affairs. Linbarger’s academic career was interrupted by active service as a 2nd Lieutenant in World War II. In 1943 he was sent to China to coordinate military intelligence operations, where he befriended Chiang Kai-shek. At war’s end he had risen to the rank of major. In 1947, he moved to the Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies in Washington DC where he served as Professor of Asiatic Studies. He used his wartime experience to write the book Psychological Warfare (1948), which is regarded by many in the field as a classic text. He was recalled to advise the British forces in the Malayan Emergency and the US Eighth Army in the Korean War. Paul called himself “a visitor to small wars”, and refrained from involvement in Vietnam. He is known to have done undocumented work for the CIA. -

Towards a Robust and Scholarly Christian Engagement with Science Fiction

Digital Collections @ Dordt Faculty Work Comprehensive List 7-19-2019 Towards a Robust and Scholarly Christian Engagement with Science Fiction Joshua Matthews Dordt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Matthews, J. (2019). Towards a Robust and Scholarly Christian Engagement with Science Fiction. Christian Scholar's Review, 48 (4), 337. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work/ 1233 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Work Comprehensive List by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards a Robust and Scholarly Christian Engagement with Science Fiction Keywords learning and scholarship, science fiction, criticism, faith Disciplines Christianity Comments Online access: https://christianscholars.com/towards-a-robust-and-scholarly-christian-engagement-with-science-fiction/ This article is available at Digital Collections @ Dordt: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work/1233 Towards a Robust and Scholarly Christian Engagement with Science Fiction It is well known that that great Christian apologist and critic of seventeenth-century English literature, C. S. Lewis, also wrote and critically engaged with science fiction (SF). But in his early 1960s essay “On Science Fiction,” Lewis reminds us that his love of SF came during a time in the early 20th century when it was derided by critics as crude and juvenile. Lewis observes a “double paradox” in the history of SF: “it began to be popular when it least deserved popularity, and to excite critical contempt as soon as it ceased to be wholly contemptible.”1 Fast- forward 50 years and even the crustiest critic who harbors contempt for the fantastical visions of SF has to pay it serious attention.