Samata: Keeping Girls in Secondary School Project Implementation Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 731 to BE ANSWERED on 23Rd JULY, 2018

LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 731 TO BE ANSWERED ON 23rd JULY, 2018 Survey for Petrol Pumps 731. SHRI BHAGWANTH KHUBA: पेट्रोलियम एवं प्राकृ तिक गैस मंत्री Will the Minister of PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government have conducted proposes to conduct any survey to open new petrol pumps and new LPG distributorships/dealerships in Hyderabad and Karnataka and if so, the details thereof; and (b) the name of the places where new petrol pump and LPG dealership have been opened / proposed to be opened open after the said survey? ANSWER पेट्रोलियम एवं प्राकृ तिक गैस मंत्री (श्री धमेन्द्र प्रधान) MINISTER OF PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS (SHRI DHARMENDRA PRADHAN) (a) Expansion of Retail Outlets (ROs) and LPG distributorships network by Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) in the country is a continuous process. ROs and LPG distributorships are set up by OMCs at identified locations based on field survey and feasibility studies. Locations found to be having sufficient potential as well as economically viable are rostered in the Marketing Plans for setting up ROs and LPG distributorships. (b) OMCs have commissioned 342 ROs (IOCL:143, BPCL:89 & HPCL:110) in Karnataka and Hyderabad during the last three years and current year. State/District/Location-wise number of ROs where Letter of Intents have been issued by OMCs in the State of Karnataka and Hyderabad as on 01.07.2018 is given in Annexure-I. Details of locations advertised by OMCs for LPG distributorship in the state of Karnataka is given in Annexure-II. -

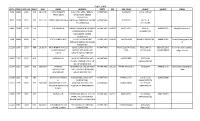

Of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN

Page 1 of 426 AUTO YEAR IVPR_SRL PAGE DOB NAME ADDRESS STATE PIN REG_NUM QUALIF MOBILE EMAIL 7356 1994S 2091 345 28.04.49 KRISHNAMSETY D-12, IVRI, QTRS, HEBBAL, KARNATAKA VCI/85/94 B.V.Sc./APAU/ PRABHODAS BANGALORE-580024 KARNATAKA 8992 1994S 3750 425 03.01.43 SATYA NARAYAN SAHA IVRI PO HA FARM BANGALORE- KARNATAKA VCI/92/94 B.V.Sc. & 24 KARNATAKA A.H./CU/66 6466 1994S 1188 295 DINTARAN PAL ANIMAL NUTRITION DIV NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2150/91 BVSc & 9480613205 [email protected] ADUGODI HOSUR ROAD AH/BCKVV/91 BANGALORE 560030 KARNATAKA 7200 1994S 1931 337 KAJAL SANKAR ROY SCIENTIST (SS) NIANP KARNATAKA 560030 WB/2254/93 BVSc&AH/BCKVV/93 9448974024 [email protected] ADNGODI BANGLORE 560030 m KARNATAKA 12229 1995 2593 488 26.08.39 KRISHNAMURTHY.R,S/ #1645, 19TH CROSS 7TH KARNATAKA APSVC/205/94,VCI/61 BVSC/UNI OF 080 25721645 krishnamurthy.rayakot O VEERASWAMY SECTOR, 3RD MAIN HSR 7/95 MADRAS/62 09480258795 [email protected] NAIDU LAYOUT, BANGALORE-560 102. 14837 1995 5242 626 SADASHIV M. MUDLAJE FARMS BALNAD KARNATAKA KAESVC/805/ BVSC/UAS VILLAGE UJRRHADE PUTTUR BANGALORE/69 DA KA KARANATAKA 11694 1995 2049 460 29/04/69 JAMBAGI ADIGANGA EXTENSION AREA KARNATAKA 591220 KARNATAKA/2417/ BVSC&AH 9448187670 shekharjambagi@gmai RAJASHEKHAR A/P. HARUGERI BELGAUM l.com BALAKRISHNA 591220 KARANATAKA 10289 1995 624 386 BASAVARAJA REDDY HUKKERI, BELGAUM DISTT. KARNATAKA KARSUL/437/ B.V.SC./GAS 9241059098 A.I. KARANATAKA BANGALORE/73 14212 1995 4605 592 25/07/68 RAJASHEKAR D PATIL, AMALZARI PO, BILIGI TQ, KARNATAKA KARSV/2824/ B.V.SC/UAS S/O DONKANAGOUDA BIJAPUR DT. -

Karnataka Name of Graduates' Constituency : Karnataka North West Graduates

Table of Content of Graduates' Constituency of Legislative Council Electoral Roll of the Year 2015 Name Of State: Karnataka Name of Graduates' Constituency : Karnataka North West Graduates DETAILS OF REVISION Year of revision : 2015 Type of revision : Summary Qualifying date : 01-11-2015 Date of publication : 18-01-2016 (a).Name of Graduates' Constituency : Karnataka North West Graduates Karnataka North West Graduates (b).Districts in which the aforesaid Constituency is located : Belgaum,Bagalkot,Bijapur. (c) No. and Name of Assembly Constituency Comprised within the All the Assembly Constituencies in the districts of aforesaid Graduates' Constituency : Belgaum,Bagalkot,Bijapur. TOTAL NO. OF PARTS IN THE CONSTITUENCY : 150. COMPONENTS OF THE ROLL. (A) Mother roll (B) Supplement-1 (C) Supplement-2 NET NUMBER OF ELECTORS : Male Female Others Total 141286 37801 11 179098 Part No : 111 Electoral Rolls,2015 of North West Graduates Constituency of Karnataka Legislative Council District : Bijapur Taluk/Town/City : Muddebihal Area : Muddebihal.Kuntoji,kolur,Tangadagi,Nebageri,Mudur,Kolur,L.T. Devur,Abbihal,Kavadimatii,Harindral.Geddalamari,Mudnal,Hadalageri,Handargal,Nagaral,Hadagali,Chirch ankal,Inchagal.Yargal,Gonal.S.H.Banoshi,Kamaladinni,Gangur,Chalmi,Alur,Kunchaganur,Kalagi,Amaragol, Shirol,Garasangi,Madari,Bailakur,Madinal,Gonal P.N Sl No Name of the Elector Name of Address (Place of Ordinary Qualification Business Age Sex EPIC Photo of Father/Mother/Husband Residence) Number the elector 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 L A Rajashekhar Em N A Maruthi Nagar Muddebihal M S C M Ed M Phila Lecturer 36 M Photo Not Available 2 PARAVIN AALAGUR Abdulakhadar AALAGUR .,Muddebihal, Muddebihal, B.A.,Bed. -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

Muddebihal Assembly Karnataka Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781-84 Email : [email protected] Website : http://www.indiastatelections.com Online Book Store : www.indiastatpublications.com Report No. : AFB/KA-026-0121 ISBN : 978-93-87148-19-2 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : January, 2021 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310/- © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 183 for the use of this publication. Printed in India Contents No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-10 Constituency - (Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2018, 2014, 2013 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 11-18 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population -

In the High Court of Karnataka Kalaburagi Bench

- 1 - W.P.Nos.201158-201161/2015 IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA KALABURAGI BENCH DATED THIS THE 8 TH DAY OF SEPTEMBER 2015 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE H.G.RAMESH WRIT PETITION Nos.201158-201161/2015 (KLR-RES) BETWEEN: 1. GURUNATH S/O SHANTARAM SARODE AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O TALIKOTI, TQ. MUDDEBIHAL DIST: VIJAYPUR 2. VISHWANATH S/O SHANTARAM SARODE AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O TALIKOTI, TQ. MUDDEBIHAL DIST: VIJAYPUR 3. SMT. NANABAI W/O S. DAYEPULE AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O TALIKOTI, TQ. MUDDEBIHAL DIST: VIJAYPUR 4. SMT. TULAJABAI W/O SHANTARAM DAYEPULE AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O TALIKOTI, TQ: MUDDEBIHAL DIST: VIJAYPUR .... PETITIONERS (BY SRI JAYANANDAYYA, ADVOCATE-ABSENT) AND: 1. THE STATE OF KARNATAKA REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY - 2 - W.P.Nos.201158-201161/2015 REVENUE DEPARTMENT M.S. BUILDING, BANGALORE 2. THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER VIJAYPURA 3. THE ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER VIJAYPUR 4. THE DEPUTY TAHASILDAR TALIKOT, DIST: VIJAYPURA 5. SIDDANAGOUDA S/O SHANKARAPPA TANGADAGI AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O GADISOMANAL TQ. MUDDEBIHAL, DIST: VIJAYPUR 6. RAMANGOUDA S/O SHANKAREPPA TANGADAGI AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O GADISOMANAL TQ. MUDDEBIHAL, DIST: VIJAYPUR 7. MAHADEVAPPA S/O SHANKAREPPA TANGADAGI AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O GADISOMANAL TQ. MUDDEBIHAL, DIST: VIJAYPUR 8. SHANTGOUDA S/O SHANKAREPPA TANGADAGI AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O GADISOMANAL TQ. MUDDEBIHAL, DIST: VIJAYPUR 9. NINGANGOUADA S/O SHANKAREPPA TANGADAGI AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE R/O GADISOMANAL TQ. MUDDEBIHAL, DIST: VIJAYPUR 10. NANAGOUDA S/O SHANKAREPPA TANGADAGI AGE: YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE - 3 - W.P.Nos.201158-201161/2015 R/O GADISOMANAL TQ. -

PRL. DISTRICT and SESSIONS JUDGE, VIJAYAPURA Hon. Sri

PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE, VIJAYAPURA Hon. Sri. SADANAND NARAYAN NAYAK PRL DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE Cause List Date: 27-11-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate 11.00 AM to 02.00 PM 1 R.A. 118/2020 Kalyankumar S/o Ishwarappa Kadi Sachin (HEARING) Nagathan Veerasangappa. Vs Malati W/o Laxman Bhosale 2 Civil Misc. (A.I.R.) Sunil S/o. Nathu Chavan 42/2020 Vs (FIRST HEARING) Darshan S/o. Sanjaya Rathod 3 Civil Misc. (A.I.R.) Sachin S/o. Basappa Taddewadi 43/2020 Vs (FIRST HEARING) Santosh S/o. Lakshman Magi 4 Civil Misc. (A.I.R.) Maheshkumar Sagareppa 44/2020 Kengalgutti (FIRST HEARING) Vs Chidananda Dundappa Birajdar 5 Civil Misc. (A.I.R.) Pruthviraj urf Preetham 45/2020 Vs (FIRST HEARING) Tukaram S/o Ramaning Pujari 6 R.A. 31/2013 Channappagouda Mallanagouda Kulkarni (ARGUMENTS) Patil Raghvendra IA/1/2013 Vs Madhavrao. Bhagirathibai Goudappagouda Patil BVP 7 R.A. 76/2019 Shankrevva W/o Jaapu Pawar Jahagirdhar (ARGUMENTS) Urf Lamani R/o Utnal Sanjeev IA/1/2019 Vs Venkatesh. Yashavant S/o Subbu Lamani R/o Utnal Khasnis Mahipati Hanamtarao. 2.45 PM to 05.00 PM 8 Misc 317/2018 Sadiqpeeran S/o. Sahebhussaini Sri. (ORDERS) Patel L.M.Hanchali Vs Hussainbasha S/o. Moulasab M.R.Indikar Mamadapur Cases listed below are adjourned due to Covid 19 9 EX 33/2020 07-01-2021 Manager, Majlis-E-Millat Urban V.V.Khade (STEPS) (2.45 PM to 05.00 Credit Souharda PM) Sahakari,Vijayapur Vs Zaherabi Kasimsab Niralgi 1/3 PRL. -

Present the Hon'ble Mr.Justice N.Ananda and The

- -1 `IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA GULBARGA BENCH DATED THIS THE 17 TH DAY OF SEPTEMBER, 2014 PRESENT THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE N.ANANDA AND THE HON’BLE MR.JUSTICE S.N.SATYANARAYANA WRIT APPEAL NO.50087/2013 (KLR-RR) BETWEEN 1. SHANKARAPPA BASAPPA TANGADAGI SINCE DECEASED BY HIS LRS 1-A) SIDDANAGOUDA S/O. SHANKARAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 57 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE 1-B) RAMANAGOUDA S/O. SHNAKARAPP TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 50 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE 1-C) MAHADEVAPPA S/O. SHAANKARAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 55 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE 1-D) SHANTAGOUDA S/O. SHANKARAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 52 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE 1-E) NINGANAGOUDA S/O. SHANKARPP TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 46 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE 1-F) NANAGOUDA S/O. SHANKARAPP TNGADAGI AGED ABOUT 48 YEARS, OCC: AGRICULTURE 2. SHIVABASAPPA BASAPPA TANGADAGI SINCE DECEASED BY HIS LRS., 2-A) BASANAGOUDA S/O. SHIVABASAPPA TANGADAGI - -2 AGED ABOUT 49 YEARS, OCC: SERVICE 2-B) BHIMANAGOUDA S/O. SHIVABASAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 43 YEARS, OCC: AGRL. 2-C) PRABHUGOUDA S/O. SHIVABASAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 36 YEARS, OCC: AGRL. 3. GURAPPA BASAPPA TANGADAGI SINCE DECEASED BY HIS LRS., 3-A) LAXMIBAI W/O. GURAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 65 YEARS, OCC: H.H.WORK 3-B) YAMANAPPA @ YAMANOOR S/O GURAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 42 YEARS, OCC: AGRI. 4. SAHEBGOUDA S/O SIDRAMAPPA TANGADAGI AGED ABOUT 52 YEARS, OCC: AGRL. ALL R/O GDISOMANAL VILLAGE TQ: MUDDEBIHAL, DIST: BIJAPUR ... PETITIONERS (BY M/S.SHIVAYOGIMATH ASSOCIATES) AND 1. THE STATE OF KARNATAKA REP. BY ITS SECRETARY REVENUE DEPARTMENT M.S. BUILDING, BANGALORE-1 2. -

Gram Panchayat Human Development

Gram Panchayat Human Development Index Ranking in the State - Districtwise Rank Rank Rank Standard Rank in in Health in Education in District Taluk Gram Panchayat of Living HDI the the Index the Index the Index State State State State Bagalkot Badami Kotikal 0.1537 2186 0.7905 5744 0.7164 1148 0.4432 2829 Bagalkot Badami Jalihal 0.1381 2807 1.0000 1 0.6287 4042 0.4428 2844 Bagalkot Badami Cholachagud 0.1216 3539 1.0000 1 0.6636 2995 0.4322 3211 Bagalkot Badami Nandikeshwar 0.1186 3666 0.9255 4748 0.7163 1149 0.4284 3319 Bagalkot Badami Hangaragi 0.1036 4270 1.0000 1 0.7058 1500 0.4182 3659 Bagalkot Badami Mangalore 0.1057 4181 1.0000 1 0.6851 2265 0.4169 3700 Bagalkot Badami Hebbali 0.1031 4284 1.0000 1 0.6985 1757 0.4160 3727 Bagalkot Badami Sulikeri 0.1049 4208 1.0000 1 0.6835 2319 0.4155 3740 Bagalkot Badami Belur 0.1335 3011 0.8722 5365 0.5940 4742 0.4105 3875 Bagalkot Badami Kittali 0.0967 4541 1.0000 1 0.6652 2938 0.4007 4141 Bagalkot Badami Kataraki 0.1054 4194 1.0000 1 0.6054 4549 0.3996 4163 Bagalkot Badami Khanapur S.K. 0.1120 3946 0.9255 4748 0.6112 4436 0.3986 4187 Bagalkot Badami Kaknur 0.1156 3787 0.8359 5608 0.6550 3309 0.3985 4191 Bagalkot Badami Neelgund 0.0936 4682 1.0000 1 0.6740 2644 0.3981 4196 Bagalkot Badami Parvati 0.1151 3813 1.0000 1 0.5368 5375 0.3953 4269 Bagalkot Badami Narasapura 0.0902 4801 1.0000 1 0.6836 2313 0.3950 4276 Bagalkot Badami Fakirbhudihal 0.0922 4725 1.0000 1 0.6673 2874 0.3948 4281 Bagalkot Badami Kainakatti 0.1024 4312 0.9758 2796 0.6097 4464 0.3935 4315 Bagalkot Badami Haldur 0.0911 4762 -

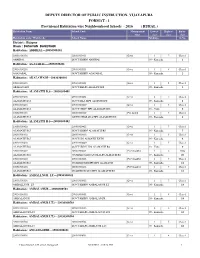

Format-1 Vijayapura

DEPUTYDIRECTOROFPUBLICINSTRUCTION,VIJAYAPURA FORMAT-1 ProvisionalHabitationwiseNeighbourhoodSchools-2016(RURAL) HabitationName SchoolCode Management Lowest Highest Entry type class class class Habitationcode/Wardcode SchoolName Medium Sl.No. District:Bijapur Block:BASAVANBAGEWADI Habitation:ABBIHAL---29030300101 29030300101 29030300101 Govt. 1 7 Class1 ABBIHAL GOVTKBHPSABBIHAL 05-Kannada 1 Habitation:AGASABAL---29030300201 29030300201 29030300201 Govt. 1 8 Class1 AGASABAL GOVTKBHPSAGASABAL 05-Kannada 2 Habitation:AKALAWADI---29030300301 29030300301 29030300301 Govt. 1 5 Class1 AKALAWADI GOVTKBLPSAKALAWADI 05-Kannada 3 Habitation:ALAMATTID.S---29030300401 29030300401 29030300401 Govt. 1 7 Class1 ALAMATTID.S GOVTMLAMPSALMATTIDS 05-Kannada 4 29030300401 29030300419 Govt. 1 8 Class1 ALAMATTID.S GOVTURDUHPSALAMATTIDS 18-Urdu 5 29030300401 29030300429 PvtAided 1 7 Class1 ALAMATTID.S AIDEDSHARADAHPSALAMATTIDS 05-Kannada 6 Habitation:ALAMATTIR.S---29030300402 29030300402 29030300402 Govt. 1 7 Class1 ALAMATTIR.S GOVTKBHPSALAMATTIRS 05-Kannada 7 29030300402 29030300413 Govt. 1 5 Class1 ALAMATTIR.S GOVTLPSALMATTIEXTN 05-Kannada 8 29030300402 29030300420 Govt. 1 5 Class1 ALAMATTIR.S GOVTURDULPSALAMATTIRS 18-Urdu 9 29030300402 29030300431 PvtUnaided 1 5 LKG ALAMATTIR.S UNAIDEDGEETANJALILPSALMATTIRS 05-Kannada 10 29030300402 29030300416 PvtUnaided 1 7 Class1 ALAMATTIR.S UNAIDEDMHMPSHPSALAMATTI 05-Kannada 11 29030300402 29030300418 PvtUnaided 1 7 Class1 ALAMATTIR.S UNAIDEDB.M.NHPSALAMATTIRS 05-Kannada 12 Habitation:AMBALLNURLT---29030300501 29030300501 -

District Taluk Gram Panchayat Year Work Name Type of Building

Estimated Expenditure For District Taluk Gram Panchayat Year Work Name Type Of Building Expenditure Work status Amount SC/ST Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Formation of dranage in chavanabhavi village Drinking Water Supply 198000 0 0 completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 I.E.C. IEC 84000 41000 0 completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Construction of Drainage from Hand pump to Nala at Kyatanadoni village Drainage 45000 44000 0 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Construction of Concrete road to Anganawadi at Donkamadu village CC Road 45000 44500 0 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Construction of Dobi-Ghat at Khilarahatti village Dhobi Ghat 50000 48000 0 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Providing Stone paving from Gram Devata Katta at A-Hulagabal village Stone Paving 50000 49000 0 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Construction of Dobi-Ghat at Chavanabhavi village Dhobi Ghat 60000 59000 0 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Construction of Ladies Latrine at A-Hulagabal LT village Construction of Toilet 50000 48000 48000 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2006-07 Construction of Ladies Latrine at Adavi Somanal village Construction of Toilet 100000 98000 98000 Completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2007-08 I.E.C IEC 10000 10000 0 completed Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2007-08 Construction of concrete road from KBMPS School to Anaganawadi Centre at Kyatanadoni village. School Compound and Buildings75000 74000 0 Completed Providing stone paving from Anganawadi to Dyamanna Kudalagi house at Donkamadu village. Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2007-08 Stone Paving 80000 79000 0 Completed (2008-09) Bijapur Muddebihal Adavi Somanal 2007-08 Construction of drainage from Gram Devate katta to Nala at Adavi Hulagabal village. -

社唧i斂 Cg優鍊tp罄 瑰糯异ai斂 母 牆阪 母j鬆扚 §G乜i斂效 C瑰繗仴囡A

PÀ£ÁðlPÀ ¸ÀPÁðgÀ - CgÀtå E¯ÁSÉ ¥ÀæzsÁ£À ªÀÄÄRå CgÀtå ¸ÀAgÀPÀëuÁ¢üPÁj (ªÀÄÄRå¸ÀÜgÀÄ, CgÀtå ¥ÀqÉ) ºÁUÀÆ DAiÉÄÌ ¥Áæ¢üPÁgÀ EªÀgÀ PÀbÉÃj CgÀtå ¨sÀªÀ£À, ªÀįÉèñÀégÀA, ¨ÉAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ-560003 C¢ü¸ÀÆZÀ£É ¸ÀASÉå: ©9-ªÀCC-«ªÀ-5/2015-16, ¢£ÁAPÀ: 22.03.2016 ªÀ®AiÀÄ CgÀuÁå¢üPÁj ºÀÄzÉÝAiÀÄ ¥ÀƪÀð¨Á« ¥ÀjÃPÉë §gÉAiÀÄ®Ä CºÀðvÉ ºÉÆA¢gÀĪÀ C¨sÀåyðUÀ¼À ¥ÀnÖ (©.J¹ì ªÀÄvÀÄÛ EvÀgÀ C¨sÀåyðUÀ¼ÀÄ) Sl.No. Application ID Register No. Name of the Candidate Father Name Gender Examination Centre 1 50013099 20001 ABHIJEET BELAVI ASHOK BELAVI MALE Belagavi 2 50016319 20002 ABHISHEK UMESH UDOSHI UMESH UDOSHI MALE Belagavi 3 50001204 20003 Abubakar Kodihal Kashimrajak MALE Belagavi 4 50000294 20004 ADINATH BASARIKHODI SHREEKANT MALE Belagavi 5 50021395 20005 AIZAZKHAN PATHAN SADRUDDIN MALE Belagavi 6 50006193 20006 AJAREKAR SUMYABI A KADAR A KADAR FEMALE Belagavi 7 50011074 20007 AJAY VERNEKAR AMARNATHA VERNEKAR MALE Belagavi 8 50009969 20008 AJAYKUMAR MATHAPATI BASAVARAJ MALE Belagavi 9 50007632 20009 AKASHAY HADIMANI BASAVARAJ MALE Belagavi 10 50009043 20010 AKSHATA DADDIMANI VITTAL FEMALE Belagavi 11 50011348 20011 AKSHATA PAWAR AMBAJI PAWAR FEMALE Belagavi 12 50016859 20012 AKSHATHA M KARJAGIMATH MAHANTESH KARJAGIMATH FEMALE Belagavi 13 50014918 20013 AKSHAYKUMAR ROTTAYYANAVARAMATH VIJAY MALE Belagavi 14 50022133 20014 ALLAPPA KANKANAWADI ASHOK MALE Belagavi 15 50009302 20015 AMAR MOKASHI ARUNRAO MALE Belagavi 16 50006355 20016 AMEED NADAF PINJAR RAMAJAN MALE Belagavi 17 50015923 20017 AMIR KHALEELAHMED KITTUR KHALEELAHMED MALE Belagavi 18 50007966 20018 AMIT ANIL KADAM ANIL S KADAM MALE Belagavi 19 50017475 20019 AMIT G KORI GANESH G KORI MALE Belagavi 20 50022373 20020 AMIT HOLKAR RAGHAVENDRA MALE Belagavi 21 50021633 20021 ANAND BADIGER DUNDAPPA MALE Belagavi 22 50008770 20022 ANAND D MAILANNAVAR DURGAPPA MALE Belagavi 23 50009262 20023 ANAND HUKKERI BASAPPA MALE Belagavi 24 50022950 20024 ANAND JAYAGOUDAR BUJABALI JAYAGOUDAR MALE Belagavi 25 50000516 20025 ANAND M BUDRAKATTI MALLAPPA MALE Belagavi 26 50016146 20026 ANAND NAIK SHIVAGOND MALE Belagavi Page 1 of 339 Sl.No.