PDF Book, Philosophy of Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

INTUITION .THE PHILOSOPHY of HENRI BERGSON By

THE RHYTHM OF PHILOSOPHY: INTUITION ·ANI? PHILOSO~IDC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON By CAROLE TABOR FlSHER Bachelor Of Arts Taylor University Upland, Indiana .. 1983 Submitted ~o the Faculty of the Graduate College of the · Oklahoma State University in partial fulfi11ment of the requirements for . the Degree of . Master of Arts May, 1990 Oklahoma State. Univ. Library THE RHY1HM OF PlllLOSOPHY: INTUITION ' AND PfnLoSOPlllC METHOD IN .THE PHILOSOPHY OF HENRI BERGSON Thesis Approved: vt4;;. e ·~lu .. ·~ests AdVIsor /l4.t--OZ. ·~ ,£__ '', 13~6350' ii · ,. PREFACE The writing of this thesis has bee~ a tiring, enjoyable, :Qustrating and challenging experience. M.,Bergson has introduced me to ·a whole new way of doing . philosophy which has put vitality into the process. I have caught a Bergson bug. His vision of a collaboration of philosophers using his intuitional m~thod to correct, each others' work and patiently compile a body of philosophic know: ledge is inspiring. I hope I have done him justice in my description of that vision. If I have succeeded and that vision catches your imagination I hope you Will make the effort to apply it. Please let me know of your effort, your successes and your failures. With the current challenges to rationalist epistemology, I believe the time has come to give Bergson's method a try. My discovery of Bergson is. the culmination of a development of my thought, one that started long before I began my work at Oklahoma State. However, there are some people there who deserv~. special thanks for awakening me from my ' "''' analytic slumber. -

Duration, Temporality and Self

Duration, Temporality and Self: Prospects for the Future of Bergsonism by Elena Fell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire 2007 2 Student Declaration Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that white registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. Material submitted for another award I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate Type of Award Doctor of Philosophy Department Centre for Professional Ethics Abstract In philosophy time is one of the most difficult subjects because, notoriously, it eludes rationalization. However, Bergson succeeds in presenting time effectively as reality that exists in its own right. Time in Bergson is almost accessible, almost palpable in a discourse which overcomes certain difficulties of language and traditional thought. Bergson equates time with duration, a genuine temporal succession of phenomena defined by their position in that succession, and asserts that time is a quality belonging to the nature of all things rather than a relation between supposedly static elements. But Rergson's theory of duration is not organised, nor is it complete - fragments of it are embedded in discussions of various aspects of psychology, evolution, matter, and movement. My first task is therefore to extract the theory of duration from Bergson's major texts in Chapters 2-4. -

151545957.Pdf

Universit´ede Montr´eal Towards a Philosophical Reconstruction of the Dialogue between Modern Physics and Advaita Ved¯anta: An Inquiry into the Concepts of ¯ak¯a´sa, Vacuum and Reality par Jonathan Duquette Facult´ede th´eologie et de sciences des religions Th`ese pr´esent´ee `ala Facult´edes ´etudes sup´erieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de Philosophiae Doctor (Ph.D.) en sciences des religions Septembre 2010 c Jonathan Duquette, 2010 Universit´ede Montr´eal Facult´edes ´etudes sup´erieures et postdoctorales Cette th`ese intitul´ee: Towards A Philosophical Reconstruction of the Dialogue between Modern Physics and Advaita Ved¯anta: An Inquiry into the Concepts of ¯ak¯a´sa, Vacuum and Reality pr´esent´ee par: Jonathan Duquette a ´et´e´evalu´ee par un jury compos´edes personnes suivantes: Patrice Brodeur, pr´esident-rapporteur Trichur S. Rukmani, directrice de recherche Normand Mousseau, codirecteur de recherche Solange Lefebvre, membre du jury Varadaraja Raman, examinateur externe Karine Bates, repr´esentante du doyen de la FESP ii Abstract Toward the end of the 19th century, the Hindu monk and reformer Swami Vivekananda claimed that modern science was inevitably converging towards Advaita Ved¯anta, an important philosophico-religious system in Hinduism. In the decades that followed, in the midst of the revolution occasioned by the emergence of Einstein’s relativity and quantum physics, a growing number of authors claimed to discover striking “par- allels” between Advaita Ved¯anta and modern physics. Such claims of convergence have continued to the present day, especially in relation to quantum physics. In this dissertation, an attempt is made to critically examine such claims by engaging a de- tailed comparative analysis of two concepts: ¯ak¯a´sa in Advaita Ved¯anta and vacuum in quantum physics. -

Physics Needs Philosophy. Philosophy Needs Physics

Found Phys (2018) 48:481–491 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10701-018-0167-y Physics Needs Philosophy. Philosophy Needs Physics Carlo Rovelli1 Received: 4 April 2018 / Accepted: 5 April 2018 / Published online: 3 May 2018 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Contrary to claims about the irrelevance of philosophy for science, I argue that philosophy has had, and still has, far more influence on physics than is commonly assumed. I maintain that the current anti-philosophical ideology has had damaging effects on the fertility of science. I also suggest that recent important empirical results, such as the detection of the Higgs particle and gravitational waves, and the failure to detect supersymmetry where many expected to find it, question the validity of certain philosophical assumptions common among theoretical physicists, inviting us to engage in a clearer philosophical reflection on scientific method. Keywords Philosophy of physics · Aristotle · Popper · Kuhn 1. Against Philosophy is the title of a chapter of a book by one of the great physicists of the last generation: Steven Weinberg, Nobel Prize winner and one of the architects of the Standard Model of elementary particle physics [1]. Weinberg argues eloquently that philosophy is more damaging than helpful for physics—although it might pro- vide some good ideas at times, it is often a straightjacket that physicists have to free themselves from. More radically, Stephen Hawking famously wrote that “philosophy is dead” because the big questions that used to be discussed by philosophers are now in the hands of physicists [2]. Similar views are widespread among scientists, and scientists do not keep them to themselves. -

Required Readings

HPS/PHIL 93872 Spring 2006 Historical Foundations of the Quantum Theory Don Howard, Instructor Required Readings: Topic: Readings: Planck and black-body radiation. Martin Klein. “Planck, Entropy, and Quanta, 19011906.” The Natural Philosopher 1 (1963), 83-108. Martin Klein. “Einstein’s First Paper on Quanta.” The Natural Einstein and the photo-electric effect. Philosopher 2 (1963), 59-86. Max Jammer. “Regularities in Line Spectra”; “Bohr’s Theory The Bohr model of the atom and spectral of the Hydrogen Atom.” In The Conceptual Development of series. Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 62- 88. The Bohr-Sommerfeld “old” quantum Max Jammer. “The Older Quantum Theory.” In The Conceptual theory; Einstein on transition Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, probabilities. 1966, pp. 89-156. The Bohr-Kramers-Slater theory. Max Jammer. “The Transition to Quantum Mechanics.” In The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 157-195. Bose-Einstein statistics. Don Howard. “‘Nicht sein kann was nicht sein darf,’ or the Prehistory of EPR, 1909-1935: Einstein’s Early Worries about the Quantum Mechanics of Composite Systems.” In Sixty-Two Years of Uncertainty: Historical, Philosophical, and Physical Inquiries into the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. Arthur Miller, ed. New York: Plenum, 1990, pp. 61-111. Max Jammer. “The Formation of Quantum Mechanics.” In The Schrödinger and wave mechanics; Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: Heisenberg and matrix mechanics. McGraw-Hill, 1966, pp. 196-280. James T. Cushing. “Early Attempts at Causal Theories: A De Broglie and the origins of pilot-wave Stillborn Program.” In Quantum Mechanics: Historical theory. -

Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting

European Medicines Agency June 1995 CPMP/ICH/377/95 ICH Topic E 2 A Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting Step 5 NOTE FOR GUIDANCE ON CLINICAL SAFETY DATA MANAGEMENT: DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS FOR EXPEDITED REPORTING (CPMP/ICH/377/95) APPROVAL BY CPMP November 1994 DATE FOR COMING INTO OPERATION June 1995 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 85 75 Fax (44-20) 75 23 70 40 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.eu.int EMEA 2006 Reproduction and/or distribution of this document is authorised for non commercial purposes only provided the EMEA is acknowledged CLINICAL SAFETY DATA MANAGEMENT: DEFINITIONS AND STANDARDS FOR EXPEDITED REPORTING ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline 1. INTRODUCTION It is important to harmonise the way to gather and, if necessary, to take action on important clinical safety information arising during clinical development. Thus, agreed definitions and terminology, as well as procedures, will ensure uniform Good Clinical Practice standards in this area. The initiatives already undertaken for marketed medicines through the CIOMS-1 and CIOMS-2 Working Groups on expedited (alert) reports and periodic safety update reporting, respectively, are important precedents and models. However, there are special circumstances involving medicinal products under development, especially in the early stages and before any marketing experience is available. Conversely, it must be recognised that a medicinal product will be under various stages of development and/or marketing in different countries, and safety data from marketing experience will ordinarily be of interest to regulators in countries where the medicinal product is still under investigational-only (Phase 1, 2, or 3) status. -

The Role of Philosophy in a Naturalized World

EuJAP | Vol. 8 | No. 1 | 2012 ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER UDK: 1 Dummett, M. 1:53 530.1:140.8 113/119 THE ROLE OF PHILOSOPHY IN A NATURALIZED WORLD JAN FAYE University of Copenhagen ABSTRACT 1. Introduction This paper discusses the late Michael Dummett’s Why are humanists and natural scientists characterization of the estrangement between unable to understand one another? Th is physics and philosophy. It argues against those physicists who hold that modern physics, seems to be one of the two main questions rather than philosophy, can answer traditional that concern Sir Michael in his thought- metaphysical questions such as why there is provoking essay “Th e Place of Philosophy something rather than nothing. The claim is that in the European Culture.” He does not physics cannot solve metaphysical problems since metaphysical issues are in principle himself supply us with any defi nite answer, empirically underdetermined. The paper closes but suggests that philosophers in general with a critical discussion of the assumption of do not know much about the natural some cosmologists that the Universe was created sciences, and therefore do not dare to speak out of nothing: In contrast to this misleading up against the natural scientists (and those assumption, it is proposed that the Universe has a necessary existence and that the present epoch who do are not interested in the same kind after the Big Bang is a contingent realization of of problems as the scientists.) Moreover, the Universe. because of the great success of the natural sciences scientists are often arrogant by Keywords: : Dummett, physics, philosophy, meta- assuming that the only knowledge we physics, underdetermination, cosmology can have is the knowledge they are able to provide. -

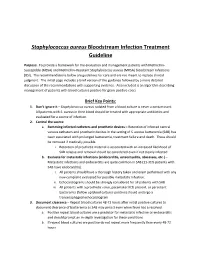

Staphylococcus Aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline

Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline Purpose: To provide a framework for the evaluation and management patients with Methicillin- Susceptible (MSSA) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSI). The recommendations below are guidelines for care and are not meant to replace clinical judgment. The initial page includes a brief version of the guidance followed by a more detailed discussion of the recommendations with supporting evidence. Also included is an algorithm describing management of patients with blood cultures positive for gram-positive cocci. Brief Key Points: 1. Don’t ignore it – Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a blood culture is never a contaminant. All patients with S. aureus in their blood should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and evaluated for a source of infection. 2. Control the source a. Removing infected catheters and prosthetic devices – Retention of infected central venous catheters and prosthetic devices in the setting of S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) has been associated with prolonged bacteremia, treatment failure and death. These should be removed if medically possible. i. Retention of prosthetic material is associated with an increased likelihood of SAB relapse and removal should be considered even if not clearly infected b. Evaluate for metastatic infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, abscesses, etc.) – Metastatic infections and endocarditis are quite common in SAB (11-31% patients with SAB have endocarditis). i. All patients should have a thorough history taken and exam performed with any new complaint evaluated for possible metastatic infection. ii. Echocardiograms should be strongly considered for all patients with SAB iii. All patients with a prosthetic valve, pacemaker/ICD present, or persistent bacteremia (follow up blood cultures positive) should undergo a transesophageal echocardiogram 3. -

The Relationship of Drought Frequency and Duration to Time Scales

Eighth Conference on Applied Climatology, 17-22 January 1993, Anaheim, California if ~ THE RELATIONSHIP OF DROUGHT FREQUENCY AND DURATION TO TIME SCALES Thomas B. McKee, Nolan J. Doesken and John Kleist Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 1.0 INTRODUCTION Five practical issues become important in any analysis of drought. These include: 1) time scale, 2) The definition of drought has continually been probability, 3) precipitation deficit, 4) application of the a stumbling block for drought monitoring and analysis. definition to precipitation and to the five water supply Wilhite and Glantz (1985) completed a thorough review variables, and 5) the relationship of the definition to the of dozens of drought definitions and identified six impacts of drought. Frequency, duration and intensity overall categories: meteorological, climatological, of drought all become functions that depend on the atmospheric, agricultural, hydrologic and water implicitly or explicitly established time scales. Our management. Dracup et al. (1980) also reviewed experience in providing drought information to a definitions. All points of view seem to agree that collection of decision makers in Colorado is that they drought is a condition of insufficient moisture caused have a need for current conditions expressed in terms by a deficit in precipitation over some time period. of probability, water deficit, and water supply as a Difficulties are primarily related to the time period over percent of average using recent climatic history (the which deficits accumulate and to the connection of the last 30 to 100 years) as the basis for comparison. No deficit in precipitation to deficits in usable water single drought definition or analysis method has sources and the impacts that ensue. -

John Von Neumann's “Impossibility Proof” in a Historical Perspective’, Physis 32 (1995), Pp

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE Published: Louis Caruana, ‘John von Neumann's “Impossibility Proof” in a Historical Perspective’, Physis 32 (1995), pp. 109-124. JOHN VON NEUMANN'S ‘IMPOSSIBILITY PROOF’ IN A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ABSTRACT John von Neumann's proof that quantum mechanics is logically incompatible with hidden varibales has been the object of extensive study both by physicists and by historians. The latter have concentrated mainly on the way the proof was interpreted, accepted and rejected between 1932, when it was published, and 1966, when J.S. Bell published the first explicit identification of the mistake it involved. What is proposed in this paper is an investigation into the origins of the proof rather than the aftermath. In the first section, a brief overview of the his personal life and his proof is given to set the scene. There follows a discussion on the merits of using here the historical method employed elsewhere by Andrew Warwick. It will be argued that a study of the origins of von Neumann's proof shows how there is an interaction between the following factors: the broad issues within a specific culture, the learning process of the theoretical physicist concerned, and the conceptual techniques available. In our case, the ‘conceptual technology’ employed by von Neumann is identified as the method of axiomatisation. 1. INTRODUCTION A full biography of John von Neumann is not yet available. Moreover, it seems that there is a lack of extended historical work on the origin of his contributions to quantum mechanics. -

Miracles: Metaphysics, Physics, and Physicalism

Religious Studies 44, 125–147 f 2008 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S0034412507009262 Printed in the United Kingdom Miracles: metaphysics, physics, and physicalism KIRK MCDERMID Department of Philosophy and Religion, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07403 Abstract: Debates about the metaphysical compatibility between miracles and natural laws often appear to prejudge the issue by either adopting or rejecting a strong physicalist thesis (the idea that the physical is all that exists). The operative component of physicalism is a causal closure principle: that every caused event is a physically caused event. If physicalism and this strong causal closure principle are accepted, then supernatural interventions are ruled out tout court, while rejecting physicalism gives miracles metaphysical carte blanche. This paper argues for a more moderate version of physicalism that respects important physicalist intuitions about causal closure while allowing for miracles’ logical possibility. A recent proposal for a specific mechanism for the production of miracles (Larmer (1996d)) is criticized and rejected. In its place, two separate mechanisms (suitable for deterministic and indeterministic worlds, respectively) are proposed that do conform to a more moderate physicalism, and their potential and limitations are explored. Introduction Many writers assert that miracles are law-violating instances (Swinburne (1970), Odegard (1982), Collier (1996), MacGill (1996)), but respondents claim that this idea is variously incoherent (McKinnon (1967), Flew (1967)), or false (Basinger (1984), Larmer (1996a)). The incoherence charge only applies to a strictly Humean view of laws as merely accounts of what actually happened (McKinnon (1967)), not to more robust views of laws as representing some variety of physical necessity or causal power.