Version 2020-04-20 Bobolink (Dolichonyx Oryzivorus) Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 7-13-2003 Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie Maiken Winter State University of New York Shawn E. Hawks University of Minnesota - Crookston Jill A. Shaffer USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Douglas H. Johnson USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Winter, Maiken; Hawks, Shawn E.; Shaffer, Jill A.; and Johnson, Douglas H., "Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie" (2003). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 160. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/160 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in The Prairie Naturalist 35(3): September 2003. Published by the Great Plains Natural Science Society http://www.fhsu.edu/biology/pn/prairienat.htm Guidelines for Finding Nests of Passerine Birds in Tallgrass Prairie MAIKEN WINTER!, SHAWN E. HAWKS2, JILL A. SHAFFER, and DOUGLAS H. JOHNSON State University of New York, College of Environmental Sciences and Forestry, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210 (MW) University of Minnesota, Crookston, MN 58105 (SEH) U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, 8711 37th St. SE, Jamestown, ND 5840 I (lAS, DHJ) ABSTRACT -- The productivity of birds is one of the most critical components of their natural history affected by habitat quality. -

Territory Establishment in Red-Winged Blackbirds: Importance of Aggressive Behavior and Experience

Condor, 81:258-264 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1979 TERRITORY ESTABLISHMENT IN RED-WINGED BLACKBIRDS: IMPORTANCE OF AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE KEN YASUKAWA In this paper I assess the importance of most intense when males attempt to acquire aggression in acquisition of initial breeding their initial territories. Competition be- territory by male Red-winged Blackbirds tween males occurs primarily among birds (Agelaius phoeniceus). The ability to ac- in fully adult plumage, that is, birds who are quire territory is expected to depend upon at least two years old. The existence of con- that portion of male quality determined pri- siderable competition for territories is in- marily by intrasexual selection. dicated by: rapid replacement following re- Darwin (1859, 1871) formulated the the- moval (Orians 1961); high conspecific male ory of sexual selection to account for certain trespass rates (Peek 1971); and defense of apparent exceptions to his concept of natu- suboptimal areas (Orians 1961, Case and ral selection, but evolutionary biologists Hewitt 1963, Robertson 1972, 1973). now realize that sexual selection is a special Male Red-winged Blackbirds establish case of individual selection relating to the territories by taking over unoccupied areas, evolutionary implications of competitive intruding between occupied areas and ex- mating. Most zoologists agree with Darwin panding, or displacing established residents that sexual selection has two phases: intra- (Nero 1956). As defined here, males are sexual, usually in the form of competition “successful” when they possess suitable between males; and intersexual or epigam- nesting sites and are not displaced by other ic, usually in the form of female choice of males prior to the onset of nesting by fe- a mate (Selander 1972, Emlen 1973, Brown males (regardless of whether they acquire 1975, Wilson 1975, but see also Mayr 1972). -

Territory and Mating System in the Bobolink, Dolichonyx Oryzivorus

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1975 Territory and Mating System in the Bobolink, Dolichonyx Oryzivorus Arlo J. Raim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Raim, Arlo J., "Territory and Mating System in the Bobolink, Dolichonyx Oryzivorus" (1975). Master's Theses. 2493. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2493 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TERRITORY AND MATING SYSTEM IN THE BOBOLINK, DOLICHONYX ORYZIVORUS by Arlo J . Raim A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1975 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Richard Brewer, for suggestions and discussions about the study and for reviewing and making suggestions on preparation of the manuscript. I would also like to thank Dr. Jack Wood for suggestions on clarifying the man uscript, and Errol Moerdyk, Jerome Wenger, and Jerome Robins for their assistance in the field. Arlo J. Raim Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. -

Effects of Management Practices on Grassland Birds: Bobolink

EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: BOBOLINK Grasslands Ecosystem Initiative Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center U.S. Geological Survey Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 This report is one in a series of literature syntheses on North American grassland birds. The need for these reports was identified by the Prairie Pothole Joint Venture (PPJV), a part of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The PPJV recently adopted a new goal, to stabilize or increase populations of declining grassland- and wetland-associated wildlife species in the Prairie Pothole Region. To further that objective, it is essential to understand the habitat needs of birds other than waterfowl, and how management practices affect their habitats. The focus of these reports is on management of breeding habitat, particularly in the northern Great Plains. Suggested citation: Dechant, J. A., M. L. Sondreal, D. H. Johnson, L. D. Igl, C. M. Goldade, A. L. Zimmerman, and B. R. Euliss. 1999 (revised 2001). Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Bobolink. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND. 24 pages. Species for which syntheses are available or are in preparation: American Bittern Grasshopper Sparrow Mountain Plover Baird’s Sparrow Marbled Godwit Henslow’s Sparrow Long-billed Curlew Le Conte’s Sparrow Willet Nelson’s Sharp-tailed Sparrow Wilson’s Phalarope Vesper Sparrow Upland Sandpiper Savannah Sparrow Greater Prairie-Chicken Lark Sparrow Lesser Prairie-Chicken Field Sparrow Northern Harrier Clay-colored Sparrow Swainson’s Hawk Chestnut-collared Longspur Ferruginous Hawk McCown’s Longspur Short-eared Owl Dickcissel Burrowing Owl Lark Bunting Horned Lark Bobolink Sedge Wren Eastern Meadowlark Loggerhead Shrike Western Meadowlark Sprague’s Pipit Brown-headed Cowbird EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: BOBOLINK Jill A. -

Status of 10 Bird Species of Conservation Concern, Vol. 3

Status of 10 Bird Species of Conservation Concern in US Fish & Wildlife Service Region 6: Volume III Draft Report to: United States Fish & Wildlife Service, Region 6 Denver, Colorado By Christopher J. Butler, Ph.D., Nathan Hillis and Katrina Hucks Department of Biology University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 73034-5209 Apr 30, 2015 Table of Contents Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa) ................................................................................................................... 3 Franklin’s Gull (Leucophaeus pipixcan) ....................................................................................................... 11 Black Tern (Chlidonias niger)....................................................................................................................... 19 Black-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus erythropthalmus) ....................................................................................... 27 Prairie Falcon (Falco mexicanus) ................................................................................................................. 34 Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) .................................................................................................... 42 Bell’s Vireo (Vireo bellii) .............................................................................................................................. 49 McCown’s Longspur (Rhynchophanes mccownii) ....................................................................................... 57 Vesper Sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus) -

Rotational Grazing of Beef Cattle to Support Bobolink Breeding Success

VOLUME 14, ISSUE 2, ARTICLE 13 Campomizzi, A. J., Z. M. Lebrun-Southcott, L. D. Van Vliet, and G. A. Morris. 2019. Rotational grazing of beef cattle to support Bobolink breeding success. Avian Conservation and Ecology 14(2):13. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01420-140213 Copyright © 2019 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Rotational grazing of beef cattle to support Bobolink breeding success Andrew J. Campomizzi 1, Zoé M. Lebrun-Southcott 1, Laura D. Van Vliet 2 and Gerald A. Morris 1 1Bird Ecology and Conservation Ontario, 2Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association ABSTRACT. Conservation actions for the federally and provincially threatened Bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) in Ontario, Canada are ongoing in agricultural landscapes, including pastures. However, conditions conducive to Bobolink fledging young from breeding territories in rotationally grazed beef cattle (Bos taurus) pastures are not well understood. We tested two management strategies designed to provide habitat where Bobolink could fledge young in rotationally grazed pastures. We conducted (1) a refuge paddock experiment using a crossover design, comparing fledging success when paddocks were ungrazed in one year to when they were grazed in another year; and (2) a light spring grazing experiment. Additionally, we explored associations between fledging of young from territories with cattle stocking rate and date that cattle first entered paddocks. We used spot mapping and nest monitoring to determine if young fledged in 83 Bobolink territories in 2016 and 72 territories in 2017 on six farms in the Ottawa Valley, Ontario. In the refuge paddock experiment, 54% (N = 28) of Bobolink territories fledged young in eight ungrazed paddocks compared to 16% (N = 25) when these paddocks were grazed in another breeding season. -

Grassland Bird Response to Enhanced Vegetation Diversity in Restoration

Iowa State University Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2011 Grassland bird response to enhanced vegetation diversity in restoration plantings in the Spring Run Complex of northwestern Iowa Jennifer Amy Vogel Iowa State University Recommended Citation Vogel, Jennifer Amy, "Grassland bird response to enhanced vegetation diversity in restoration plantings in the Spring Run Complex of northwestern Iowa" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 10324. http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10324 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Iowa State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grassland bird response to enhanced vegetation diversity in restoration plantings in the Spring Run Complex of northwestern Iowa by Jennifer Amy Vogel A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Program of Study Committee: Rolf R. Koford, Co-major Professor David L. Otis, Co-major Professor Stephen J. Dinsmore Philip M. Dixon Brian J. Wilsey Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2011 Copyright © Jennifer Amy Vogel, 2011. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv CHAPTER ONE. GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 Dissertation Organization 4 Literature Cited 5 CHAPTER TWO. BIRD RESPONSE TO ENHANCED VEGETATION DIVERSITY IN GRASSLAND RESTORATION PLANTINGS 11 Abstract 11 Introduction 12 Methods 15 Results 20 Discussion 23 Acknowledgements 27 Literature Cited 28 Figures and Tables 33 Appendices 41 CHAPTER THREE. REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS OF RED-WINGED BLACKBIRDS IN RESTORED GRASSLANDS 43 Abstract 43 Introduction 44 Methods 47 Results 52 Discussion 53 Acknowledgements 57 Literature Cited 57 Figures and Tables 64 CHAPTER FOUR. -

Bobolink (Dolichonyx Oryzivorus) in Argentina

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus in Canada THREATENED 2010 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 42 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Carl Savignac for writing the provisional status report on the Bobolink, Dolichonyx oryzivorus, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. The contractor’s involvement with the writing of the status report ended with the acceptance of the provisional report. Any modifications to the status report during the subsequent preparation of the interim status report were overseen by Marty Leonard, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Goglu des prés (Dolichonyx oryzivorus) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Bobolink — Photo by Carl Savignac, with permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2010. Catalogue CW69-14/600-2010E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-15956-0 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2010 Common name Bobolink Scientific name Dolichonyx oryzivorus Status Threatened Reason for designation Over 25% of the global population of this grassland bird species breeds in Canada, which is the northern portion of its range. -

Bobolink Dolichonyx Oryzivorus

Appendix A: Birds Bobolink Dolichonyx oryzivorus Federal Listing N/A State Listing N/A Global Rank G5 State Rank S4 Regional Status Very High Photo by Pamela Hunt Justification (Reason for Concern in NH) Populations of most grassland birds are in strong decline, both in the Northeast and sometimes across larger portions of their continental ranges. For this reason, most species were included in the Northeast list of SGCN, with those that occur regularly in NH retained for the NH WAP revision. Based on BBS data (Sauer et al. 2014), Bobolink populations in New Hampshire have declined at 1.87% annually since 1966 (1.9%/year from 2003‐2013). These trends are more negative in regional data: BCR 14 = ‐4.42%/year, BCR 30 = ‐2.48%/year. Although the declines seen in the BBS are widespread, they have not manifest as significant loss of range occupancy in repeated Breeding Bird Atlases in the northeast (McGowan and Corwin 2008, Renfrew 2013, MassAudubon 2014). Distribution Bobolinks breed across the northern United States and southern Canada from Oregon and British Columbia to Virginia and (rarely) Newfoundland. They winter east of the Andes in South America from Bolivia to northern Argentina. The species occurs throughout New Hampshire where suitable habitat is present. Habitat Bobolinks breed in a variety of grassland habitats, although these generally contain a mix of tall grasses and scattered leafy forbs such as legumes or dandelions (Martin and Gavin 1995). A relatively dense litter layer is also important, a feature that is more prevalent in older fields (e.g., eight of more years since planting/reseeding, Bollinger and Gavin 1992). -

Fiftee N Vertebrate Beginnings the Chordates

Hickman−Roberts−Larson: 15. Vertebrate Beginnings: Text © The McGraw−Hill Animal Diversity, Third The Chordates Companies, 2002 Edition 15 chapter •••••• fifteen Vertebrate Beginnings The Chordates It’s a Long Way from Amphioxus Along the more southern coasts of North America, half buried in sand on the seafloor,lives a small fishlike translucent animal quietly filtering organic particles from seawater.Inconspicuous, of no commercial value and largely unknown, this creature is nonetheless one of the famous animals of classical zoology.It is amphioxus, an animal that wonderfully exhibits the four distinctive hallmarks of the phylum Chordata—(1) dorsal, tubular nerve cord overlying (2) a supportive notochord, (3) pharyngeal slits for filter feeding, and (4) a postanal tail for propulsion—all wrapped up in one creature with textbook simplicity. Amphioxus is an animal that might have been designed by a zoologist for the classroom. During the nineteenth century,with inter- est in vertebrate ancestry running high, amphioxus was considered by many to resemble closely the direct ancestor of the vertebrates. Its exalted position was later acknowledged by Philip Pope in a poem sung to the tune of “Tipperary.”It ends with the refrain: It’s a long way from amphioxus It’s a long way to us, It’s a long way from amphioxus To the meanest human cuss. Well,it’s good-bye to fins and gill slits And it’s welcome lungs and hair, It’s a long, long way from amphioxus But we all came from there. But amphioxus’place in the sun was not to endure.For one thing,amphioxus lacks one of the most important of vertebrate charac- teristics,a distinct head with special sense organs and the equipment for shifting to an active predatory mode of life. -

2020-2021 NEBRASKA BIRD LIST See Science Olympiad General Rules, Eye Protection & Other Policies on As They Apply to Every Event

2020-2021 NEBRASKA BIRD LIST See Science Olympiad General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event Kingdom – ANIMALIA ORDER: Pelecaniformes ORDER: Gruiformes Pelicans (Pelecanidae) Rails, Gallinules, and Coots (Rallidae) Phylum – CHORDATA American White Pelican Pelecanus Clapper Rail Rallus longirostris Subphylum – VERTEBRATA erythrorhynchos Sora Bitterns, Herons, and Allies Purple Gallinule Class - AVES (Ardeidae) American Coot Family Group (Family Name) American Bittern Cranes (Gruidae) Common Name Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias Sandhill Crane Antigone canadensis [Scientific name is in italics] Snowy Egret Egretta thula Whooping Crane Grus americana Green Heron ORDER: Anseriformes Black-crowned Night-heron ORDER: Charadriiformes Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Ibises and Spoonbills Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Black-bellied Whistling-duck (Threskiornithidae) American Golden-Plover Snow Goose Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Piping Plover Charadrius melodus Canada Goose Branta canadensis Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Trumpeter Swan ORDER: Suliformes Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Wood Duck Aix sponsa Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) American Oystercatcher Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Double-crested Cormorant Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) Northern Shoveler Phalacrocorax auritus Black-necked Stilt Green-winged Teal Darters (Anhingida) American Avocet Recurvirostra Canvasback Anhinga Anhinga anhinga americana Hooded Merganser Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Sandpipers, Phalaropes, -

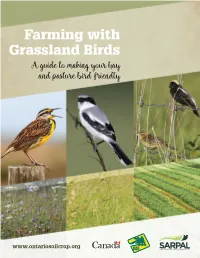

Farming with Grassland Birds a Guide to Making Your Hay and Pasture Bird Friendly

Farming with Grassland Birds A guide to making your hay and pasture bird friendly www.ontariosoilcrop.org Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 1 WHY THE CONCERN ABOUT GRASSLAND BIRDS? 2 WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW: BASIC GRASSLAND BIRD ECOLOGY 3 FORAGE AND PASTURE IN ONTARIO 4 PRINCIPLES OF FORAGE AND PASTURE MANAGEMENT 4 GRASSLAND BIRDS IN GRAZING SYSTEMS 5 Continuous Grazing 5 Deferred Rotational Grazing 5 Simple Rotational Grazing 6 Farming with Intensive Rotational Grazing 6 Grassland Birds GRASSLAND BIRDS IN FORAGE SYSTEMS 7 Early Haying 7 A guide to making your hay Middle Haying 7 and pasture bird friendly Late Haying 7 BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES 8 PRODUCER WORKBOOK 11 Step 1: Which Fields are Most Important for Grassland Birds? 11 Step 2: Goal Setting and Action Plan Development 14 APPENDIX: IDENTIFYING COMMON GRASSLAND BIRDS 18 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES FOR IDENTIFYING BIRDS Back Cover Acknowledgements Authors: Jack Kyle and Ronald Reid Reviewers: Hayley Paquette, Chris Risley, Paul Smith and Laura Van Vliet August, 2016. Species at Risk Partnerships on Agricultural Lands This workbook was funded through the Species at Risk Partnerships on Agricultural Lands (SARPAL) program, an Environment and Climate Change Canada initiative focused on working with farmers to support the recovery of species at risk on agricultural land. SARPAL funds priority conservation actions currently focused in Ontario on supporting the Bobolink and the American Badger. Visit www.ontariosoilcrop.org for more information. The views expressed herein are solely those of the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association. Bobolink This project was undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada.