Introduction: Honour Violence, Law and Power in Upper Sindh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government of Sindh Finance Department

2021-22 Finance Department Government of Sindh 1 SC12102(102) GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 51,652,000 ______________ Total: 51,652,000 ______________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT ____________________________________________________________________________________________ BUILDINGS ____________________________________________________________________________________________ P./ADP DDO Functional-Cum-Object Classification & Budget NO. NO. Particular Of Scheme Estimates 2021 - 2022 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Rs 01 GENERAL PUBLIC SERVICE 011 EXECUTIVE & LEGISLATIVE ORGANS, FINANCAL 0111 EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE ORGANS 011103 PROVINCIAL EXECUTIVE KQ5003 SECRETARY (GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE) ADP No : 0733 KQ21221562 Constt. of Multi-storeyed Flats Phase-II at Sindh Governor's 51,652,000 House, Karachi (48 Nos.) including MT-s A12470 Others 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ Total Sub Sector BUILDINGS 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ TOTAL SECTOR GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ 2 SC12104(104) SERVICES GENERAL ADMIN & COORDINATION Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 1,432,976,000 ______________ Total: 1,432,976,000 ______________ _____________________________________________________________________________ -

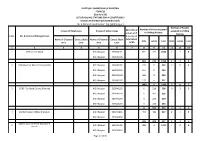

National Assembly Polling Scheme

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN FORM 28 [See Rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY Election to the National Assembly Sindh No. & Name of Constituency:- NA-208 Khairpur-I Number of Booths Number of Voters assigned In case of Rural areas In case of Urban Areas Serial No of assigned to Polling to Polling Stations voters on E Stations S.No. No. & Name of Polling Station A in case of Name of Electoral Census Block Name of Electoral Census Block bifurcation Male Female Total Male Female Total Area Code Area Code of EA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 1 GPS Saleem Abad MC Khairpur 333040101 861 735 1596 2 2 4 MC Khairpur 333040106 861 735 1596 2 2 4 2 GPS Boys Faiz Abad Colony (Male) MC Khairpur 333040102 312 0 312 3 0 3 MC Khairpur 333040103 254 0 254 MC Khairpur 333040104 306 0 306 MC Khairpur 333040105 217 0 217 1089 0 1089 3 0 3 3 GGPS Faiz Abad Colony (Female) MC Khairpur 333040102 0 228 228 0 3 3 MC Khairpur 333040103 0 202 202 MC Khairpur 333040104 0 250 250 MC Khairpur 333040105 0 233 233 0 913 913 0 3 3 4 District Council Office Khairpur-I MC Khairpur 333040201 495 422 917 2 1 3 MC Khairpur 333040206 495 422 917 2 1 3 District Council Office Khairpur-II 5 MC Khairpur 333050405 1231 0 1231 4 0 4 (Male) MC Khairpur 333050410 Page 1 of 130 Number of Booths Number of Voters assigned In case of Rural areas In case of Urban Areas Serial No of assigned to Polling to Polling Stations voters on E Stations S.No. -

Irrigation and Field Patterns in the Indus Delta. Mushtaq-Ur Rahman Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1960 Irrigation and Field Patterns in the Indus Delta. Mushtaq-ur Rahman Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Rahman, Mushtaq-ur, "Irrigation and Field Patterns in the Indus Delta." (1960). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 601. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/601 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRRIGATION AND FIELD PATTERNS IN THE INDUS DELTA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Muehtaq-ur Rahman B. A. Hons., M, A, Karachi University, 1955 June, I960 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr. William G. Mclntire for his direction and supervision of the dissertation at every stage; to Doctors Fred B. Kniffen, R. C. West, W.G.Haag and John H. Vann, Jr. , faculty members of the Department of Geography and Anthropology, Louisiana State University, for their valuable criticism of the manuscript and continued assistance. Thanks are due to Mr. Rodman E. Snead, graduate student, Louisiana State University, for permission to use climatic data collected by him in Pakistan; to Mr. -

The Musalman Races Found in Sindh

A SHORT SKETCH, HISTORICAL AND TRADITIONAL, OF THE MUSALMAN RACES FOUND IN SINDH, BALUCHISTAN AND AFGHANISTAN, THEIR GENEALOGICAL SUB-DIVISIONS AND SEPTS, TOGETHER WITH AN ETHNOLOGICAL AND ETHNOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT, BY SHEIKH SADIK ALÍ SHER ALÍ, ANSÀRI, DEPUTY COLLECTOR IN SINDH. PRINTED AT THE COMMISSIONER’S PRESS. 1901. Reproduced By SANI HUSSAIN PANHWAR September 2010; The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 DEDICATION. To ROBERT GILES, Esquire, MA., OLE., Commissioner in Sindh, This Volume is dedicated, As a humble token of the most sincere feelings of esteem for his private worth and public services, And his most kind and liberal treatment OF THE MUSALMAN LANDHOLDERS IN THE PROVINCE OF SINDH, ВY HIS OLD SUBORDINATE, THE COMPILER. The Musalman Races; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. In 1889, while I was Deputy Collector in the Frontier District of Upper Sindh, I was desired by B. Giles, Esquire, then Deputy Commissioner of that district, to prepare a Note on the Baloch and Birahoi tribes, showing their tribal connections and the feuds existing between their various branches, and other details. Accordingly, I prepared a Note on these two tribes and submitted it to him in May 1890. The Note was revised by me at the direction of C. E. S. Steele, Esquire, when he became Deputy Commissioner of the above district, and a copy of it was furnished to him. It was revised a third time in August 1895, and a copy was submitted to H. C. Mules, Esquire, after he took charge of the district, and at my request the revised Note was printed at the Commissioner-in-Sindh’s Press in 1896, and copies of it were supplied to all the District and Divisional officers. -

History of Kalhoras

HISTORY OF KALHORAS (Kalhora Daur Hukoomat) Review by: M.H. Panhwar Dr. Ghulam Muhammad Lakho has written this book, which has seen dedicated to (i) Mr. Mazharul Haq Siddiqui and (ii) me i.e., M.H. Panhwar. This book in itself is a classic, even the classic on the subject covering 102 years of Kalhora ascendancy up to their fall and is the first of its kind so far produced. With such important work, I ask my self: “do I deserve the importance that Dr. Lakho the author, has bestowed on me?” I wonder, wonder and re-wonder and then it reminds me of the Socrates who said: “People consider me wise because I know nothing”. The book is actually a Ph.D thesis on approval of which the writer was awarded the Doctorate in 1999 by the University of Sindh. The thesis has been touched further as needful for rendering it press worthy. The book has seen the light of the day in 2004 as a publication of Anjuman Ithad-e-Abbasia Pakistan, Karachi. There is so much knowledge known now and also unknown, in each and every sphere of every subject that one can’t fully master a single field or a few chapters or sub-chapters or even a part of a sub-paragraph of it during the whole life time. Research methods have changed. Field research is a new technology, to collect data statistically and draw conclusions. I get credit because research on Sindh is lacking. My interest in Sindh goes back, when at age of six, a branch for “Separation of Sindh from Bomaby” movement was formed in our village and I started wondering what Sindh was, is and will be? Since then I have read every thing about Sindh including history, with interest as well as concern, whether the original contemporary historians who wrote in Persian or English, had grasped the factual history, as times and environments had molded it and they had embarked to write History of Kalhoras; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 about. -

S U M M a R Y Works & Services Department Annual

{290} S U M M A R Y WORKS & SERVICES DEPARTMENT ANNUAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2013-14 (Rs. In million) Throw- On-Going New Total Grand Financial Projection Sr No. of No. of No. of Sub-Sector forward as FPA Total No. Schemes Schemes Schemes on 01.07.13 Capital Revenue Total Capital Revenue Total Capital Revenue Total (15+16) 2014-15 2015-16 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Works & Services Department A) Normal Roads 1 General 10762.290 26 2391.333 0.000 2391.333 1 100.000 0.000 100.000 27 2491.333 0.000 2491.333 0.000 2491.333 4218.203 3878.252 2 Improvement 20742.323 161 2846.060 0.000 2846.060 91 1441.645 15.000 1456.645 252 4287.705 15.000 4302.705 0.000 4302.705 9363.748 7777.239 3 Construction 19172.159 210 2488.995 0.000 2488.995 226 1906.049 0.000 1906.049 436 4395.044 0.000 4395.044 0.000 4395.044 9501.924 4421.097 4 Bridges 1458.123 8 296.264 0.000 296.264 1 50.000 0.000 50.000 9 346.264 0.000 346.264 0.000 346.264 595.562 595.562 Total Normal Roads 52134.894 405 8022.652 0.000 8022.652 319 3497.694 15.000 3512.694 724 11520.346 15.000 11535.346 0.000 11535.346 23679.437 16672.151 B) Strategic Roads 1 Improvement 421.253 2 29.000 0.000 29.000 0 0.000 0.000 0.000 2 29.000 0.000 29.000 0.000 29.000 196.127 196.127 2 Construction 9857.839 20 535.589 0.000 535.589 3 31.430 0.000 31.430 23 567.019 0.000 567.019 0.000 567.019 4679.848 4610.972 Total Strategic Roads 10279.092 22 564.589 0.000 564.589 3 31.430 0.000 31.430 25 596.019 0.000 596.019 0.000 596.019 4875.975 4807.099 C) Foreign Aided Project 1790.320 4 1268.635 0.000 1268.635 0 0.000 0.000 0.000 4 1268.635 0.000 1268.635 8860.948 10129.583 2051.024 0.000 Total Foreign Aided Projects 1790.320 4 1268.635 0.000 1268.635 0 0.000 0.000 0.000 4 1268.635 0.000 1268.635 8860.948 10129.583 2051.024 0.000 Total Roads & Bridges:- 64204.306 431 9855.876 0.000 9855.876 322 3529.124 15.000 3544.124 753 13385.000 15.000 13400.000 8860.948 22260.948 30606.436 21479.249 D) Buildings 1 Govt. -

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia -

Degradation of Indus Delta, Removal Mangroves Forestland Its Causes: a Case Study of Indus River Delta

Sindh Univ. Res. Jour. (Sci. Ser. ) Vol.43 (1) 67-72 (2011) SINDH UNIVERSITY RESEARCH JOURNAL (SCIENCE SERIES) Degradation of Indus delta, Removal mangroves forestland Its Causes: A Case study of Indus River delta 1 2 3 N. H. CHANDIO , M. M. ANWAR and A. A. CHANDIO 1Department of Geography, Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur, Sindh, Pakistan 2Department of Geography, the Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan 3Department of Political Science, Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur, Sindh Pakistan *Corresponding Author: N. H. Chandio, E-mail: [email protected] , Cell No. 03003142263 Received 20th October 2010 and Revised 16th March 2011) Abstract: Indus River delta and its mangroves are fighting for their survival, due to shortage of fresh water, from Kotri last two decades. Life on the delta is facing a lot of troubles, especially the deltas flora and fauna. Are facing significant challenges as they are very dependent on a steady flow of freshwater, saline sea water is increasing on surface and sub-surface toward the coastal districts of the Sindh. Fertile land is converting infertile land, local inhabitants are migrating from the area. mangroves are washed away from the area. Sea water intrusion is increasing day by day, and the of intrusion is 80 acres of delta land per day. About 38 percent area of mangroves forest has been reduced in last twenty years. The construction of various Dams, Canals and barrages is main cause of degradation of the delta and the mangroves forest. The study shows that fresh water in the River may push the sea water intrusion backward which will help the survival of the mangroves forest. -

C:\NARAD-08\History of Sindh\Si

1 Introduction The geographical Position of Sindh he Sindh as it exists today is bound in the North by Bhawalpur Tin the south by Arabian Sea, to east by Hallar range of Hills and mountains and in the west by sandy desert. On the map this land mass occupies the position between 23 degrees and 29 degrees latitude and in the eastern hemisphere it lies between 67 and 70 degrees longitudes. Thus in width is spread across 120 miles and length is 700 miles. Birth of Sindh Geologists have divided the age of the earth into Eras and eras in turn have been further divided into Epochs. Three eras in time line are described as (1) Cenozoic, which stretches to 65.5 million years. (2) Mesozoic Era which stretches from beyond 65.5 million years to 22 crore 55 lakh years and (3) Paleozoic era which is between 57 crore 5 lakh years. All this is in the realm of cosmic timeline. In the opinion of the Geologists in the tertiary age the entire north India including Sindh northern part of India emerged as a land mass 22 f History of Sindh Introduction f 23 and in place of raving sea now we find ice clad peaks of Himalayan the mountainous regions there are lakes and ponds and sandy region range and the present day Sindh emerged during that upheaval. As is totally dependent on the scanty rainfall. It is said if there is rain all per today’s map Sindh occupies the territory of 47,569 square miles. the flora fauna blooms in the desert and people get mouthful otherwise One astonishing fact brought to light by the geologists is that the there is starvation! (Vase ta Thar, Na ta bar). -

Lower Indus Basin Irrigation System: a Critical Analysis of Sindh Water Challenges 2014-15 Organization of Provincial Water Brief

Sindh Water Briefing Lower Indus Basin Irrigation System: A Critical Analysis of Sindh Water Challenges 2014-15 Organization of Provincial Water Brief This provincial water brief is divided into six sections. The next second section will be divulging upon the provincial water challenges or, in other words, the necessity of addressing the provincial policy issues hinderingbetter governance and management of water resources in Sindh Province. The third section establishes the background and history of irrigation of Sindh as well as the hydraulic reframing of the Indus River Basin in the nineteenth and twentieth century. The fourth part is actually a wake-up call to emergent harsh realities constituting the present hydraulic crisis that needs immediate redressal. The fifth section elucidates the typical problems of policy framing especially in common resources management such as water, forests, pastures and grazing lands, etc. The last and sixth section clues about the Next Steps in the formulation of Sindh Water Policy. Water Challenges in Lower Indus Basin The costs and benefits of building the Indus Basin and maintaining vast and intricate water infrastructure and irrigation system are controversial and endless. One thing that is however unmistakably clear is that, in the absence of the redressal of growing problems and meeting of varied challenges, the prevalent crisis of irrigation water sector would continue to push costs escalating and thus, ultimately rendering the whole system unbearably inefficient in the near future and unsustainable in the long run. Sindh is the lower riparian of the Indus River system and therefore most vulnerable to a variety of environmental, economic and social costs associated with the upstream water development. -

Pakistan's Sindh Province

MEMORANDUM October 29, 2015 To: Hon. Brad Sherman Attention: Kinsey Kiriakos From: K. Alan Kronstadt, Specialist in South Asian Affairs, x7-5415 Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Subject: Pakistan’s Sindh Province This memorandum responds to your request for information on Pakistan’s Sindh province, including specific discussion of its Thatta and Badin districts. Content may appear in other CRS products. Please contact me if you need further assistance. Overview1 Sindh is one of Pakistan’s four provinces, accounting for roughly one-quarter of the country’s population in less than 18% of its land area. Its provincial capital, Karachi, is among the world’s largest megacities, and also the site of significant sectarian, ethnic, and political violence. Covering more than 54,000 square miles of southeastern Pakistan (about the size of Florida, see Figure 1), Sindh stretches from the Jacobabad district in the north to the vast Indus River delta wetlands abutting the Arabian Sea and India in the south, and from the thinly-populated Dadu district in the west to the Thar Desert and a militarized border with India to the east (see Figure 2). One-third of Pakistan’s 650-mile Arabian Sea coastline is in Sindh. The vast majority of Sindh’s residents live at or near the final few hundred miles of the Indus’s course. Official government population statistics continue to be based on the most recent national census in 1998, which put Sindh’s population at 30.4 million out of Pakistan’s then-total 132 million, with 52% living in rural areas. -

Khairpur District 2020

SESSIONS PROCLAIMED OFFENDERS OF DISTRICT KHAIRPUR. S.No Range District P.S FIR No Under Section Name of Accused Father's Name Residential Address CNIC NO. Date of PO 1 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 17/2010 302-324-PPC Sabir Allah Dino Chandio Phull Road Arain Tehsil 01.12.2010 Murtaza Meerani Larkana 2 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 240/2010 302-PPC Fateh Muhammad Gangho Khan Goth Saeed Bijrani tehsil 07.08.2017 - Murtaza Meerani Nandwani tangwani 3 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 240/2010 302-PPC Gul Sher Gangho Khan Goth Saeed Bijrani tehsil 07.08.2017 - Murtaza Meerani Nandwani tangwani 4 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 36/2011 302-PPC Muhammad Ali Abdul Kareem Memon Therhi 45203- 01.06.2012 Murtaza Meerani 3176878-3 5 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 50/2011 365B-PPC Mst.Khalida Muhammad Yousif Muhalla Sarai Ghanwar 23.12.2015 - Murtaza Meerani 14/2012 506/2-PPC Shehwani Khan 6 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 65/2011 302-PPC Feroze Raheem Bux Domki Faiz Abad Colony Tehsil 45203- 22.04.2011 Murtaza Meerani Khairpur 4829104-5 7 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 65/2011 302-PPC Shoukat Raheem Bux Domki Faiz Abad Colony Tehsil 22.04.2011 Murtaza Meerani Khairpur 8 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 65/2011 302-PPC Raheem Dad Muhammad Moosa Faiz Abad Colony Tehsil 45203- 22.04.2011 Murtaza Meerani Domki Khairpur 0805855-3 9 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 167/2011 302-PPC Jumoon Nazal Kharoos Shahnawaz Kharoos Tehsil 15.07.2011 Murtaza Meerani Kingri 10 Sukkur Khairpur Shaheed SI 167/2011 302-PPC Moar Nazal Kharoos Shahnawaz Kharoos Tehsil 15.07.2011 Murtaza Meerani Kingri 11 Sukkur