The Environmental Context of the Neolithic Monuments on the Brodgar Isthmus, Mainland, 2 Orkney 3 Bates, C.R.1, Bates, M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orkney Islands the Orkney Islands

The by Carolyn Emerick Orkney Islands Let me take you down, cause we’re goin’ to... Skara Brae! The Islands of Orkney are a mystical place decline prior to the Viking invasion. Why it steeped in history and legend. Like the rest was declining is yet another mystery. It would of the British Isles, Orkney is an amalgam of appear that either the Picts required the aid of influences. The ancients left their mark from pre- Vikings, or that their situation left them wide history with their standing stones and neolithic open for a foreign invador to move in. settlements. Then came the Picts, however they What is known, is that the Viking settlement remain even more of a mystery as the Picts left of Orkney was so complete that virtually no very little evidence of their existence in Orkney place names of Pictish origin survive. In the behind. So scarce is the evidence, in fact, that rest of Britain, place names can be used to show until recently scholars questioned whether they the mixed heritage and influence of the various were there at all. It was the Vikings that left their settlers, from Celt to Roman, and especially the stamp on Orkney so strongly that their influence Germanic settlers such as the Angles, Saxons, can be found in the culture to this day. Danes, and so forth. The Vikings first began settling Orkney in the The Orkney Islands are late eighth century. From the records available, shown in Red with the we can only speculate what happened to the Shetland Islands off to Picts who had been living on the Islands prior the upper right in this to Viking settlement. -

Heart of Neolithic Orkney Map and Guide

World heritage The remarkable monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1999. These sites give visitors Heart of a vivid glimpse into the creative genius, lost beliefs and everyday lives of a once flourishing culture. Neolithic World Heritage status places them alongside such globally © Raymond Besant World heritage iconic sites as the Pyramids of Egypt and the Taj Mahal. Sites Orkney site r anger service are listed because they are of importance to all of humanity. The monuments World Heritage Site Orkney’s rich cultural and natural heritage is brought to life R anger Service Ring of Brodgar by the WHS Rangers and team of The evocative Ring of Brodgar is one of the largest and volunteers who support them. best-preserved stone circles in Great Britain. It hints at Throughout the year they run a busy programme of forgotten ritual and belief. public walks, talks and family events for all ages and Skara Brae levels of interest. The village of Skara Brae with its houses and stone Every day at 1pm in June, July and August the Rangers furniture presents an insight into the daily lives of lead walks around the Ring of Brodgar to explore the Neolithic people that is unmatched in northern Europe. iconic monument and its surrounding landscape. There Stones of Stenness are also activities designed specifically for schools and education groups. The Stones of Stenness are the remains of one of the oldest stone circles in the country, raised about 5,000 years ago. The Rangers work closely with the local community to care for the historical landscape and the wildlife that Maeshowe lives in and around its monuments. -

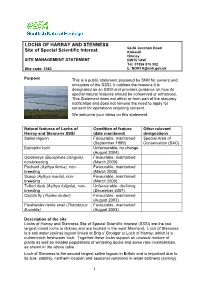

Lochs of Harray and Stenness Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) Are the Two Largest Inland Lochs in Orkney and Are Located in the West Mainland

LOCHS OF HARRAY AND STENNESS 54-56 Junction Road Site of Special Scientific Interest Kirkwall Orkney SITE MANAGEMENT STATEMENT KW15 1AW Tel: 01856 875 302 Site code: 1083 E: [email protected] Purpose This is a public statement prepared by SNH for owners and occupiers of the SSSI. It outlines the reasons it is designated as an SSSI and provides guidance on how its special natural features should be conserved or enhanced. This Statement does not affect or form part of the statutory notification and does not remove the need to apply for consent for operations requiring consent. We welcome your views on this statement. Natural features of Lochs of Condition of feature Other relevant Harray and Stenness SSSI (date monitored) designations Saline lagoon Favourable, maintained Special Area of (September 1999) Conservation (SAC) Eutrophic loch Unfavourable, no change (August 2004) Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula), Favourable, maintained non-breeding (March 2000) Pochard (Aythya ferina), non- Favourable, maintained breeding (March 2000) Scaup (Aythya marila), non- Favourable, maintained breeding (March 2000) Tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), non- Unfavourable, declining breeding (December 2007) Caddis fly (Ylodes reuteri) Favourable, maintained (August 2003) Freshwater nerite snail (Theodoxus Favourable, maintained fluviatilis) (August 2003) Description of the site Lochs of Harray and Stenness Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are the two largest inland lochs in Orkney and are located in the west Mainland. Loch of Stenness is a salt water (saline) lagoon linked at Brig o’ Brodgar to Loch of Harray, which is a nutrient-rich freshwater loch. Together these lochs support an unusual mixture of plants as well as notable populations of wintering ducks and some rare invertebrates, as shown in the above table. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

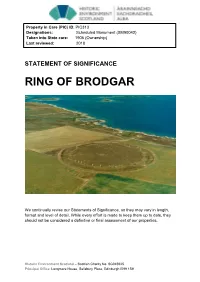

Ring of Brodgar

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC313 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90042) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2018 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE RING OF BRODGAR We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH RING OF BRODGAR, STONE CIRCLE AND HENGE BRIEF DESCRIPTION The monument comprises a massive ceremonial enclosure, or ‘henge’; its rock-cut ditch (c.123m diameter) encircling a platform with an impressive stone circle set around its circumference. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Homozygosity, inbreeding and health in European populations Ruth McQuillan PhD Thesis The University of Edinburgh 2009 Table of Contents Abstract v Acknowledgements vii Declaration xi Notes xii Abbreviations xiii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.1 Key concepts 1 1.2 Measuring inbreeding, autozygosity and homozygosity 5 1.3 Inbreeding and health in human populations 11 1.4 The genetic architecture of common complex disease 14 1.5 Thesis Aims and Objectives 17 Chapter 2: Historical and genealogical description of the population of the North Isles of Orkney 24 2.1 Introduction 24 2.2 ORCADES Pedigree Analysis: Methods 28 2.3 Results 29 2.4 Discussion 40 2.4.1 The population history of Orkney -

Orkney - the Cultural Hub of Britain in 3,500 Bc - a World Heritage Site from 1999

ORKNEY - THE CULTURAL HUB OF BRITAIN IN 3,500 BC - A WORLD HERITAGE SITE FROM 1999. THE INGENIOUS PRE-HISTORIC INHABITANTS OF WHAT ONLY BECAME SCOTLAND IN THE 9TH CENTURY AD. By James Macnaughton As indicated in the title, people lived in the Northern part of Britain for many thousands of years before it became Scotland and they were called Scots. Given its wet, cool climate and its very mountainous terrain, those inhabitants were always living on the edge, fighting to grow enough food to survive through the long winters and looking for ways to breed suitable livestock to provide both food and skins and furs from which they could fashion clothing to keep them warm and dry. 20,000 years ago, present day Scotland lay under a 1.5 Km deep ice-sheet.This is so long ago that it is difficult to imagine, but if you consider a generation to be 25 years, then this was 800 generations ago, and for us to think beyond even two or three generations of our families, this is almost unimaginable. From 11,000 years, ago, the ice was gradually melting from the South of England towards the North and this occurred more quickly along the coasts where the ice was not so thick. Early inhabitants moved North along the sea coasts as hunter gatherers and by 10,000 years ago, some of them had settled near Banchory in Aberdeenshire on the banks of the River Dee. The warming climate and the plentiful supply of fish from the river, and game from the surrounding forests, encouraged them to create a permanent settlement and to change from nomadic hunter gatherers to settled farmers. -

Introduction

Introduction On 2 July, 1266, diplomatic representatives of King Magnus vi of Norway and King Alexander iii of Scotland convened in Perth to sign a treaty aimed at bringing political order to the unstable Norse-Scottish frontier.1 Three years earlier, Alexander iii had sponsored an invasion of the Inner Hebrides, territo- ries which had long been claimed by the Norwegian crown, prompting Magnus vi’s predecessor, King Hákon iv, to launch a colossal fleet to fight back the Scottish invaders and reestablish Norway’s preeminence over the isles around the Irish Sea. Despite its ambitious scale, the Norwegian fleet was driven back, leaving those proud possessions of the Norwegian crown in the hands of a for- eign ruler.2 But it was not until 1266 that the Scottish king’s practical lordship over the Hebrides was formalized in a finalis concordia, known more commonly as the Treaty of Perth.3 In a seemingly ancillary clause, Magnus vi emphasizes his lordship over two other island provinces, Orkney and Shetland, explaining that he was to retain the lordships, homages, rents and services from them to his own ‘dominion’.4 With this simple interpolation, the Norwegian king estab- lished a political regime that would come to shape the Norse-Scottish frontier and dictate the relations between the Norwegian and Scottish crowns for an- other two centuries until, in 1468/69, those isles also fell into the hands of a Scottish king, James iii.5 During that time, Orkney and Shetland represented 1 Diplomatarium Norvegicum, 21 vols. [dn], eds. C.C.A. Lange et al., Christiania & Oslo 1849–1995, 8, no. -

The Norse Waterways of West Mainland Orkney, Scotland

The Norse Waterways of West Mainland Orkney, Scotland Martin Bates, Richard Bates, Barbara Crawford, and Alexandra Sanmark1 landscape will be that of loss of navigable Summary waterways. The potential existence of a line of This purpose of the study was to investigate the these in the West Mainland of Orkney was an idea originally developed by Barbara Crawford existence of navigable waterways in the West (Crawford 2006 a, b). This has been further Mainland of Orkney, Scotland, in the Norse period examined in recent research (Sanmark 2017; (790―1350). In the parish of Harray, a Norse farm Crawford and Sanmark 2016) to highlight an named Houseby is found. Farms with this name important gap in our knowledge of the past are known from Scandinavia and Orkney and are landscape of Orkney. usually situated by major water routes. An After the initial Norse settlement, the Orkney inspection of the oldest geographically referenced Earldom was created in the late 9th century AD maps for the parish suggests that in the past and gradually integrated into the kingdom of significant waterways across wetlands may have Norway, where it remained until the islands were extended north from the loch of Harray towards mortgaged to the Scottish kingdom in 1468. The Houseby in an area close to the power centre of fertile West Mainland of Orkney was a key area of the earldom at Birsay. The main aim of this project power for the Norse Earls, and this is where many was to test this hypothesis using palaeo- of the Earls’ seats of power were located, such as geographic reconstructions and further study of the residence at the Brough of Birsay, as well as a place-names. -

The Case of Orkney in Eighteenth-Century Scotland

Meiji Journal of Political Science and Economics Volume 3, 2014 The Enlightenment Idea of Improvement and its Discontents: The Case of Orkney in Eighteenth-Century Scotland Hiroyuki Furuya Associate Professor of the History of Economic Thought, Tokushima Bunri University, Japan Abstract The aim of this paper is to offer a view of improvement emerged in the age of Enlightenment in Scotland. This paper examines an economic debate that took place in the context of a bitterly-fought legal battle referred to as the Pundlar Process (1733–1759). It was contested between the Earl of Morton, who was a feudal superior of Orkney and Shetland, and local lairds. This paper focuses on two contemporary documents concerning the lairds as plaintiffs and Morton as defendant respectively: James Mackenzie’s The General Grievances and Oppression of the Isles of Orkney and Shetland (1750), and Thomas Hepburn’s A Letter to a Gentleman from his Friend in Orkney, Containing the True Causes of the Poverty of that Country (1760). This paper seeks to illuminate the contrasts revealed during the age of Enlightenment in Scotland by focusing on the conflict between those who tried to promote ‘improvement’ in order to adapt the economy to increased competition brought about by trade expansion after the Acts of Union of 1707, and those in the traditional, local communities who sought out alternative ways to accommodate themselves to this change. Keywords: Scottish Enlightenment, Improvement, Orkney, Pundlar Process, Thomas Hepburn 1. Introduction The age of Enlightenment in Scotland is usually associated with promising prospects such as innovations in the fields of philosophy, literature and economic thought, improvements to agricultural methods, and the dawn of the industrial revolution (Smout, 1983). -

A Contribution to the Debate on the Future of Tourism and Archaeology from Orkney Archaeology Society

Orkney Ecomuseum: A contribution to the debate on the future of tourism and archaeology from Orkney Archaeology Society Orkney Archaeology Society, 23 March 2018 Introduction OAS is not and cannot be an Orkney Tourist Board, but tourism does provide a vital opportunity to protect and promote the archaeology of our county. Tourism can help provide an income to support archaeological digs and research (e.g. the thousands raised from tourists who visit the Ness) and provides resources that that educate the public (e.g. the various museums). Tourism can also be a threat to archaeology with the erosion of sites. This paper has been prepared by OAS as a contribution to the debate on the future of tourism in Orkney and its relationship with archaeology. Cruise ships There is a concern that the increase in visitors from cruise ships means that the main sites, especially the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage sites, are so busy during peak times that is it difficult for other tourists who come to Orkney for longer periods of time to get the most out of their visits. Skara Brae can be very busy, the car parks are full at Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar and the high footfall has damaged the paths around the Ring. Tourism is a major source of income for the county and there is a perception that the mass day tourism could damage the core element; the tourist who comes for a week or more and spends money through out that time. The day visitors clearly do contribute to the local economy, not least the shops in Kirkwall, the Tourist Guides etc., but the interests of both groups and those who provide services for them, need to be balanced.