Growing Your Own Leaders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burnham Grammar School

EMBRACINGBURNHAM CHALLENGE GRAMMAR SCHOOL EMBRACING CHALLENGE SCHOOL ADMINISTRATOR JOB APPLICATION PACK CONTENTS This application pack includes: Headteacher’s Letter to candidates Job Advert Job Description Person Specification How to apply: Please download an application form from our website and send your completed form to: Mrs Anjna Pankhania Burnham Grammar School Hogfair Lane Burnham Buckinghamshire SL1 7HG Or email to [email protected] http://www.burnhamgrammar.org.uk/231/vacancies Please note we do not accept CVs Closing Date: 10 am Monday 1 July 2019 Interview Date: Wednesday 3 July 2019 It is the normal practice for references to be obtained before any formal interview. Burnham Grammar School as part of the Beeches Learning Development Trust is commit- ted to safeguarding and promoting the welfare of its students and staff and expects all staff and volunteers to share this commitment. Successful candidates will be required to undertake an enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check We encourage applications from the right candidates regardless of age, disability, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, belief or race Thank you for the interest you have shown in this vacancy HEADTEACHER’S LETTER Dear Applicant Thank you for your interest in applying for this role at Burnham Grammar School. I do hope that the information attached encourages and inspires you to make a formal application for the post. In June 2017 Burnham Grammar School created a multi-academy trust called the Beeches Learning and Development Trust in which it is the lead school and currently comprises Burnham Grammar school and Dorney School, a primary which is sponsored by the trust. -

TYPE Aylesbury Grammar School Further Offers Ma

Moving up to Secondary School in September 2014 Second Round Allocation Positions GRAMMAR SCHOOLS GRAMMAR SCHOOLS - ALLOCATION PROFILE (qualified applicants only) TYPE Further offers made under rule 4 (linked siblings), and some under rule 7 (catchment) to a distance of 1.291 Aylesbury Grammar School Academy miles. Aylesbury High School All applicants offered. Academy Beaconsfield High School All applicants offered. Foundation Burnham Grammar School Further offers made under rule 5 (distance) to 10.456 miles. Academy Chesham Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy Dr Challoner's Grammar School Further offers made under rule 4 (catchment) to a distance of 7.378 miles. Academy Dr Challoner's High School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) to a distance of 6.330 miles. Academy John Hampden Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy The Royal Grammar School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) and some under rule 6 (distance) to 8.276 miles. Academy The Royal Latin School Further offers made under rule 2 (catchment) some under rule 5 (distance) to 7.661 miles. Academy Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School All applicants offered. Academy Further offers made under rule 2{3}(catchment siblings) and some under rule 2 (catchment), to a distance of Sir William Borlase's Grammar School Academy 0.622 miles. Wycombe High School Further offers made under rule b (catchment) and some under rule d (distance) to 16.957 miles. Academy UPPER SCHOOLS UPPER SCHOOLS - ALLOCATION PROFILE TYPE Further offers made under rule b (catchment), rule c (siblings) and some under rule e (distance) to 4.038 Amersham School Academy miles. -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Schools Forum, 08/12/2020 13:30

Schools Forum agenda Date: Tuesday 8 December 2020 Time: 1.30 pm Venue: MS Teams Virtual Meeting Membership: Ms J Antrobus (Newton School), Ms J Cochrane (Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School), Ms P Coppins (Manor Farm Community Infant School), A Cranmer, Ms S Cromie (Wycombe High School), Ms J Freeman (Rye Liaison Group), Mr A Gillespie (Burnham Grammar School), Mr D Hood (Cressex Community School), Mrs J Male (Alfriston School), Mr K Patrick (Chiltern Hills Academy) (Chairman), Mrs D Rutley (Aspire PRU), Ms S Skinner (Growing Together Federation (Bowerdean & Henry Allen Nursery Schools)), Mr S Sneesby (Kite Ridge School), Ms E Stewart (Stoke Mandeville Combined School), Ms K Tamlyn (Cheddington Combined School) (Vice-Chairman), Mr B Taylor (Special School Representative), Mr A Wanford (Green Ridge Academy) and Ms J Watson (Lent Rise School) Webcasting notice Please note: this meeting may be filmed for live or subsequent broadcast via the council's website. At the start of the meeting the chairman will confirm if all or part of the meeting is being filmed. You should be aware that the council is a data controller under the Data Protection Act. Data collected during this webcast will be retained in accordance with the council’s published policy. Therefore by entering the meeting room, you are consenting to being filmed and to the possible use of those images and sound recordings for webcasting and/or training purposes. If members of the public do not wish to have their image captured they should ask the committee clerk, who will advise where to sit. If you have any queries regarding this, please contact the monitoring officer at [email protected]. -

Burnham Grammar School

EMBRACINGBURNHAM CHALLENGE GRAMMAR SCHOOL EMBRACING CHALLENGE PE Assistant/Sports Coach JOB APPLICATION PACK CONTENTS This application pack includes: Headteacher’s Letter to candidates Job Advert Job Description Person Specification Department Information How to apply: Please download an application form from our website and send your completed form to: Mrs Anjna Pankhania Burnham Grammar School Hogfair Lane Burnham Buckinghamshire SL1 7HG Or email to [email protected] http://www.burnhamgrammar.org.uk/231/vacancies Please note we do not accept CVs Closing Date: Monday 17 June 2019 It is the normal practice for references to be obtained before any formal interview. Burnham Grammar School as part of the Beeches Learning Development Trust is commit- ted to safeguarding and promoting the welfare of its students and staff and expects all staff and volunteers to share this commitment. Successful candidates will be required to undertake an enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check We encourage applications from the right candidates regardless of age, disability, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, belief or race Thank you for the interest you have shown in this vacancy HEADTEACHER’S LETTER Dear Applicant Thank you for your interest in applying for this role at Burnham Grammar School. I do hope that the information attached encourages and inspires you to make a formal application for the post. In June 2017 Burnham Grammar School created a multi-academy trust called the Beeches Learning and Development Trust in which it is the lead school and currently comprises Burnham Grammar school and Dorney School, a primary which is sponsored by the trust. -

2009 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

Grammar School Analysis.Xlsx

Report for: ACTION Item Number: 6ii Contains Confidential Yes – Appendix 5 only. Not for publication by virtue of or Exempt Information paragraph 3 of Part 1 of Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972. Title Satellite Grammar School Provision in RBWM Responsible Officer(s) Alison Alexander, Strategic Director Children’s Services Contact officer, job David Scott, Head of Education title and phone no. Member reporting Cllr Phillip Bicknell Lead Member for Education For Consideration By Cabinet Date to be Considered 29 October 2015 Implementation Date if 4 November 2015 Not Called In Affected Wards All wards Keywords/Index School Expansion, Secondary, Middle, Upper, Grammar, Academies, Satellite REPORT SUMMARY 1. The Royal Borough’s ambitions on education are that parents have choice over school places for their children and that all children have the opportunity to access high quality education, assessed as good or outstanding by Ofsted and that all children make progress in their education attainment above national levels in order to equip them with the qualifications and skills they need to succeed in their chosen career paths. 2. In September 2015 Cabinet approved a £20.5m expansion programme of six local schools, which will increase the number of secondary places by 1,380, and requested detail on Secretary of State’s decision regarding expansion of a grammar school. 3. Following the Secretary of State’s decision on 15th October 2015, this report seeks Cabinet’s approval for officers to work with Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School to undertake due diligence on options for expanding through a satellite site in Maidenhead, and carry out relevant consultation with residents. -

Dr Challoners Grammar School

Determination Case reference: ADA3659 Objector: An individual Admission authority: The Academy Trust for Dr Challoner’s Grammar School, Buckinghamshire Date of decision: 11 August 2020 Determination In accordance with section 88H(4) of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998, I do not uphold the objection to the admission arrangements for September 2021 determined by Dr Challoner’s Grammar School Trust for Dr Challoner’s Grammar School Buckinghamshire. The referral 1. Under section 88H(2) of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998, (the Act), an objection has been referred to the adjudicator by a person, (the objector), about the admission arrangements (the arrangements) for Dr Challoner’s Grammar School (the school), a selective academy school for boys aged 11 – 18 for admissions in September 2021. 2. The objection is to the school’s catchment area which is said to be in contravention of the ‘Greenwich judgement’, and therefore unlawful. The catchment area is also said to be unreasonable and to operate in a way that causes an unfairness to local applicants who do not live within the county of Buckinghamshire, specifically to applicants who reside in Chorleywood and Rickmansworth. 3. The local authority (LA) for the area in which the school is located is Buckinghamshire County Council. The LA is a party to this objection. Other parties to the objection are the objector and the Academy Trust for Dr Challoner’s Grammar School (the trust), which is the admission authority for the school. 4. The objector has lodged objections to the arrangements of two other schools, namely Chesham Grammar School (ADA3658) and Dr Challoner’s High School (ADA3660). -

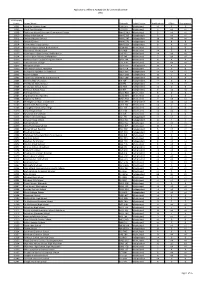

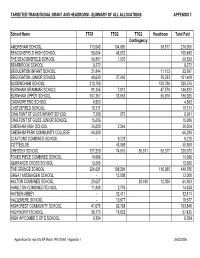

Targeted Transitional Grant and Headroom - Summary of All Allocations Appendix 1

TARGETED TRANSITIONAL GRANT AND HEADROOM - SUMMARY OF ALL ALLOCATIONS APPENDIX 1 School Name TTG1 TTG2 TTG2 Headroom Total Paid Contingency AMERSHAM SCHOOL 113,043 104,085 58,877 276,005 BEACONSFIELD HIGH SCHOOL 59,664 48,832 108,496 THE BEACONSFIELD SCHOOL 58,887 1,933 60,820 BEARBROOK SCHOOL 9,272 9,272 BROUGHTON INFANT SCHOOL 21,844 11,153 32,997 BROUGHTON JUNIOR SCHOOL 48,640 27,436 25,333 101,409 BUCKINGHAM SCHOOL 210,789 109,786 320,575 BURNHAM GRAMMAR SCHOOL 91,345 7,912 47,576 146,833 BURNHAM UPPER SCHOOL 107,357 33,653 55,915 196,925 CADMORE END SCHOOL 4,563 4,563 CASTLEFIELD SCHOOL 18,311 18,311 CHALFONT ST GILES INFANT SCHOOL 7,289 972 8,261 CHALFONT ST GILES JUNIOR SCHOOL 15,686 15,686 CHESHAM HIGH SCHOOL 26,680 2,344 29,024 CHESHAM PARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE 66,289 66,289 CLAYTONS COMBINED SCHOOL - 9,228 9,228 COTTESLOE - 45,869 45,869 CRESSEX SCHOOL 127,329 74,616 56,811 66,317 325,073 FOXES PIECE COMBINED SCHOOL 14,996 14,996 GERRARDS CROSS SCHOOL 12,665 12,665 THE GRANGE SCHOOL 224,601 108,204 116,980 449,785 GREAT MISSENDEN SCHOOL - 13,008 13,008 HALTON COMBINED SCHOOL 23,627 28,430 12,306 64,363 HAMILTON COMBINED SCHOOL 11,848 2,776 14,624 HAYDEN ABBEY - 32,411 32,411 HAZLEMERE SCHOOL - 10,677 10,677 HIGHCREST COMMUNITY SCHOOL 41,078 62,768 103,846 HIGHWORTH SCHOOL 38,773 18,652 57,425 HIGH WYCOMBE C OF E SCHOOL 9,354 9,354 Appendices for report to SF March 14th 20061 / Appendix 1 06/03/2006 School Name TTG1 TTG2 TTG2 Headroom Total Paid Contingency HOLMER GREEN SENIOR SCHOOL 67,317 3,956 71,273 IBSTONE SCHOOL 5,517 2,873 -

LGPS Employer Contribution Rates

Employer contributions % of payroll % of payroll (plus % of payroll (plus % of payro ll (plus £pm in some £pm in some £pm in some cases) cases) cases) Employer 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 Acorn Childcare N/A 16.1% 16.1% 17.0% + £75 17.0% + £75 17.0% + £75 Action for Children 13% 13.0% 13.0% 13.0% 13.0% 13.0% Action for Children (Children’s Centres) N/A N/A N/A N/A 18.2% 18.2% Action for Hearing Loss N/A N/A N/A 23.3% + £25 23.3% + £83 23.3% + £133 Adventure Learning Foundation (BCC) N/A N/A 19.4% 19.4% 19.4% 19.4% Adventure Learning Foundation (WDC) N/A N/A N/A N/A 6.2% 6.2% Alfriston School N/A N/A N/A 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% Alliance in Partnership N/A N/A N/A 18.7% 18.7% 18.7% Ambassador Theatre Group 23.0% 23.0% 23.0% 20.0% 20.0% 20.0% Amersham and Wycombe College 18.5% 18.5% 18.5% 12.0% + £13,000 12.0% + £13,583 12.0% + £14,167 Amersham School 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% Amersham Town Council 21.2% 21.2% 21.2% 14.8% + £1,167 14.8% + £1,167 14.8% + £1,250 Amey plc 12.8% 13.3% 13.8% 13.0% + £500 13.0% + £525 13.0% + £542 Archgate Cleaning 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 28.8% 28.8% 28.8% Ashridge Security Management Ltd N/A N/A N/A N/A 19.7% 19.7% ASM Metal Recycling Ltd 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% N/A N/A N/A Aston Clinton Parish Council 21.2% 21.2% 21.2% 14.8% + £117 14.8% + £117 14.8% + £125 Aylesbury College 16.4% 16.4% 16.4% 11.4% + £10,167 11.4% + £10,667 11.4% + £11,167 Aylesbury Grammar School 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% Aylesbury High School 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% 22.8% Aylesbury Town Council 21.2% 21.2% 21.2% -

ADA3658 Chesham Grammar School Objection Determination

Determination Case reference: ADA3658 Objector: An individual Admission authority: White Hill Schools Trust for Chesham Grammar School, Buckinghamshire Date of decision: 11 August 2020 Determination In accordance with section 88H(4) of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998, I do not uphold the objection to the admission arrangements for September 2021 determined by the White Hill Schools Trust for Chesham Grammar School, Buckinghamshire. The referral 1. Under section 88H(2) of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998, (the Act), an objection has been referred to the adjudicator by a person (the objector), about the admission arrangements (the arrangements) for Chesham Grammar School (the school), a selective academy school for boys and girls aged 11 – 18, for admissions in September 2021. 2. The objection is to the school’s catchment area which is said to be in contravention of the ‘Greenwich judgement’, and therefore unlawful. The catchment area is also alleged to be unreasonable and to operate to cause an unfairness to applicants who reside outside the county of Buckinghamshire, and particularly those who live in Chorleywood and Rickmansworth. 3. The local authority (LA) for the area in which the school is located is Buckinghamshire County Council. The LA is a party to this objection. Other parties to the objection are the objector and the White Hill Schools Trust (the trust) which is the admission authority for the school. 4. The objector has lodged objections to the arrangements of two other schools, namely Dr Challoner’s Grammar School (ADA3659) and Dr Challoner’s High School (ADA3660). Although the central points of the objections are the same or similar, I have dealt with the three objections as separate cases. -

1St Preference Applications for Grammar School Places from RBWM

1st preference applications for grammar school places from RBWM residents Data excludes Late Applications 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Weighted 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 Trend Average Average Slough gives result of 11+ to parents before applications deadline Bucks follows suit 1st preference analysis Holyport College opens A Ascot 8 8 7 6 6 9 1 4 4 6 5 1st preference applications for Maidenhead 144 171 165 151 171 177 201 126 106 157 126 Grammar schools, by area of Windsor 33 34 54 41 46 37 39 32 30 38 33 residence Datchet & Wraysbury 39 38 37 39 29 37 27 35 22 34 28 RBWM 224 251 263 237 252 260 268 197 162 235 192 B Total No. On Roll in Year 6 (in Ascot 117 112 113 119 103 117 117 119 122 115 119 RBWM school) by area of Maidenhead 671 719 704 730 653 693 669 730 699 696 703 residence (rbwm school means any state Windsor 296 341 321 335 323 322 330 305 369 327 344 maintained school in the borough, incl. free schools and academies) Datchet & Wraysbury 73 73 78 88 65 77 64 87 87 77 84 (January School CENSUS) RBWM 1157 1245 1216 1272 1144 1209 1180 1241 1277 1216 1251 reflects recent trends,more whilst taking accountthe overallof C All 1st preference applications Ascot 148 161 179 175 176 190 191 195 211 181 198 for Year 7, by area of residence Maidenhead 553 678 673 706 701 739 724 801 780 706 759 Windsor 50 60 63 58 62 50 61 70 81 62 73 (incl.