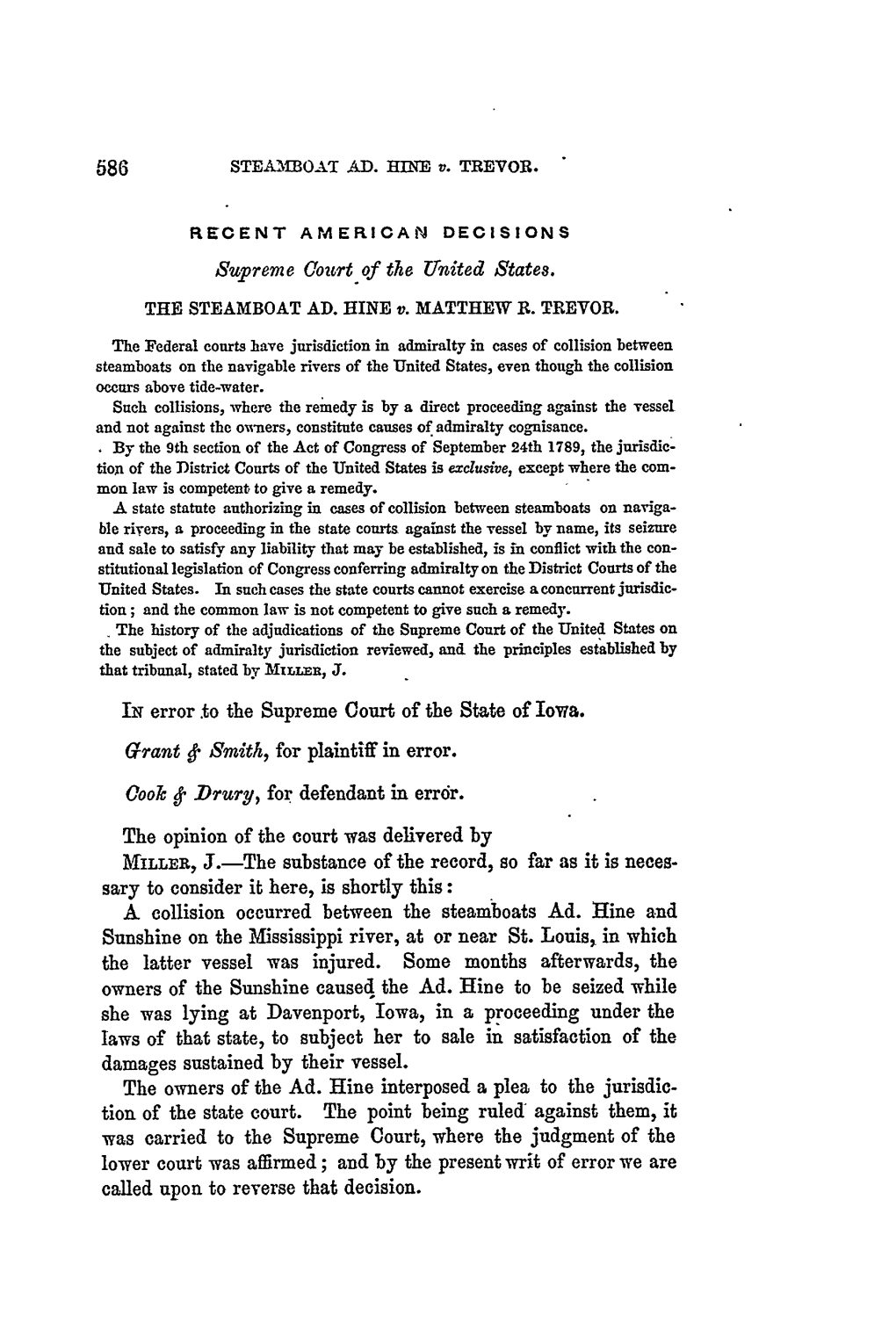

Supreme Court of the Fnited States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Abandoned Shipwrecks Act in Florida Tyler Wolanin

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst School of Public Policy Capstones School of Public Policy 2018 The Abandoned Shipwrecks Act in Florida Tyler Wolanin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cppa_capstones Part of the Law Commons, Other Legal Studies Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Wolanin, Tyler, "The Abandoned Shipwrecks Act in Florida" (2018). School of Public Policy Capstones. 47. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cppa_capstones/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Policy at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Public Policy Capstones by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Abandoned Shipwrecks Act in Florida Tyler Wolanin Master of Public Policy and Administration Capstone May 1st, 2018 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Abandoned Shipwrecks Act is a 1988 federal law that grants states jurisdiction over abandoned shipwrecks in their territorial waters. The intention of the law is to allow states to form historic preservation regimes to protect historic shipwrecks from looters and salvagers. One of the most important beneficiaries of this law is the state of Florida, with the longest coastline in the continental United States and a history of attempts to protect historic shipwrecks. This law has been criticized since inception for removing the profit incentive for salvors to discover new shipwrecks. The Act has been subjected to a considerable amount of legal criticism for the removal of jurisdiction over shipwrecks from federal admiralty courts, but it has not received attention from policy scholars. -

Indemnity Provisions in Maritime Contracts

University of Miami Law Review Volume 14 Number 1 Article 10 10-1-1959 Admiralty -- Indemnity Provisions in Maritime Contracts Michael C. Slotnick Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael C. Slotnick, Admiralty -- Indemnity Provisions in Maritime Contracts, 14 U. Miami L. Rev. 115 (1959) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol14/iss1/10 This Case Noted is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CASES NOTED ADMIRALTY-INDEMNITY PROVISIONS IN MARITIME CONTRACTS An employee of a stevedoring company was injured in the performance of a stevedoring contract between the stevedoring company and a ship- owner. The employee brought a libel against the shipowner, who impleaded the stevedoring company pursuant to an indemnity provision in the con- tract. The federal district court, having dismissed the libel on the merits, found the claim for indemnification to be moot. The court of appeals reversed and remanded the case for an adjudication of the shipowner's petition for indemnification, as well as a determination of the employee's damages. The district court, after determining the amount of damages, construed the indemnity provision to be governed by the law of the State of New York and denied recovery. Held, reversed: the shipowner was entitled to full indemnification; an indemnity provision in a stevedoring contract is governed by federal admiralty principles. -

Ship Arrests in Practice 1 FOREWORD

SHIP ARRESTS IN PRACTICE ELEVENTH EDITION 2018 A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE TO SHIP ARREST & RELEASE PROCEDURES IN 93 JURISDICTIONS WRITTEN BY MEMBERS OF THE SHIPARRESTED.COM NETWORK Ship Arrests in Practice 1 FOREWORD Welcome to the eleventh edition of Ship Arrests in Practice. When first designing this publication, I never imagined it would come this far. It is a pleasure to announce that we now have 93 jurisdictions (six more than in the previous edition) examined under the questionnaire I drafted years ago. For more than a decade now, this publication has been circulated to many industry players. It is a very welcome guide for parties willing to arrest or release a ship worldwide: suppliers, owners, insurers, P&I Clubs, law firms, and banks are some of our day to day readers. Thanks are due to all of the members contributing to this year’s publication and my special thanks goes to the members of the Editorial Committee who, as busy as we all are, have taken the time to review the publication to make it the first-rate source that it is. The law is stated as of 15th of January 2018. Felipe Arizon Editorial Committee of the Shiparrested.com network: Richard Faint, Kelly Yap, Francisco Venetucci, George Chalos, Marc de Man, Abraham Stern, and Dr. Felipe Arizon N.B.: The information contained in this book is for general purposes, providing a brief overview of the requirements to arrest or release ships in the said jurisdictions. It does not contain any legal or professional advice. For a detailed synopsis, please contact the members’ law firm. -

1Judge John Holland and the Vice- Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1797-1803: Some Introductory and Biographical Notes (Part 1)

1JUDGE JOHN HOLLAND AND THE VICE- ADMIRALTY COURT OF THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE, 1797-1803: SOME INTRODUCTORY AND BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES (PART 1) JP van Niekerk* ABSTRACT A British Vice-Admiralty Court operated at the Cape of Good Hope from 1797 until 1803. It determined both Prize causes and (a few) Instance causes. This Court, headed by a single judge, should be distinguished from the ad hoc Piracy Court, comprised of seven members of which the Admiralty judge was one, which sat twice during this period, and also from the occasional naval courts martial which were called at the Cape. The Vice-Admiralty Court’s judge, John Holland, and its main officials and practitioners were sent out from Britain. Key words: Vice-Admiralty Court; Cape of Good Hope; First British Occupation of the Cape; jurisdiction; Piracy Court; naval courts martial; Judge John Holland; other officials, practitioners and support staff of the Vice-Admiralty Court * Professor, Department of Mercantile Law, School of Law, University of South Africa. Fundamina DOI: 10.17159/2411-7870/2017/v23n2a8 Volume 23 | Number 2 | 2017 Print ISSN 1021-545X/ Online ISSN 2411-7870 pp 176-210 176 JUDGE JOHN HOLLAND AND THE VICE-ADMIRALTY COURT OF THE CAPE OF GOOD HOPE 1 Introduction When the 988 ton, triple-decker HCS Belvedere, under the command of Captain Charles Christie,1 arrived at the Cape on Saturday 3 February 1798 on her fifth voyage to the East, she had on board a man whose arrival was eagerly anticipated locally in both naval and legal circles. He was the first British judicial appointment to the recently acquired settlement and was to serve as judge of the newly created Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope. -

Pleasure Boating and Admiralty: Erie at Sea' Preble Stolz*

California Law Review VoL. 51 OCTOBER 1963 No. 4 Pleasure Boating and Admiralty: Erie at Sea' Preble Stolz* P LEASURE BOATING is basically a new phenomenon, the product of a technology that can produce small boats at modest cost and of an economy that puts such craft within the means of almost everyone.' The risks generated by this development create new legal problems. New legal problems are typically solved first, and often finally, by extension of com- mon law doctrines in the state courts. Legislative regulation and any solu- tion at the federal level are exceptional and usually come into play only as a later stage of public response.2 There is no obvious reason why our legal system should react differ- ently to the new problems presented by pleasure boating. Small boats fall easily into the class of personal property. The normal rules of sales and security interests would seem capable of extension to small boats without difficulty. The same should be true of the rules relating to the operation of pleasure boats and particularly to the liability for breach of the duty to take reasonable care for the safety of others. One would expect, therefore, that the legal problems of pleasure boating would be met with the typical response: adaptation of the common law at the state level. Unhappily this is not likely to happen. Pleasure boating has the mis- fortune of presenting basic issues in an already complex problem of fed- t I am grateful to Professor Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr. for reading the manuscript in nearly final form, and to Professor Ronan E. -

Uniformity in the Maritime Law of the United States: II

University of Pennsylvania Law Review And American Law Register FOUNDED 1852 Publh d Quarterly. November to Junm, by the University of Pennsylvania Law School. at 34th and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia. Pa. VOL. 73. MARCH, 1925. NO. 3. UNIFORMITY IN THE MARITIME LAW OF THE UNITED STATES (II).* Recognition cf the Doctrine: The Later Period. In the history of our maritime law, much favors and much is opposed to the ideal of uniformity. Judges and others, differ- ing as to its recognition as a rule of law, select whatever favors the position they are taking and declare that it illustrates the general rule, and that all the rest turns upon special, peculiar con- siderations. "As to the spectre of a lack of uniformity," said Justice Holmes, "I content myself with referring to The Ham ii- ton, 207 U. S. 398,4o6." 1 The Hamilton, in short stands for the general rule. Justice McReynolds, however, regards this case as the exception 2 and deducles his general rule from other cases. Learned justices here, as elsewhere, pass each other by, going rapidly in opposite-directions, without any real clash. Their opin- ions merely show that they disagree. A is so, B is not, says one: B is so, A is not says the other. Since they differ, they owe it to each other and to us to justify their contradictions. Justice Holmes should have explained why lack of uniformity is merely a spectre ("a ghostly apparition" . "an appearance of the * Continued from 73 U. oF PA. L. Rev. x23-14r. 'Southern Pacific Co. -

Governance and Institutional Change in Marine Insurance, 1350-1850

Governance and institutional change in marine insurance, 1350-1850 Christopher Kingston∗ Amherst College July 3, 2013 Abstract This article explores the development and diffusion of market governance institutions in the marine insurance industry as the practice of insurance spread from its early origins in medieval Italy throughout the Atlantic world. Informal governance mechanisms provided the foundation for the development of insurance law administered by specialist courts. Efforts to tax and regulate the industry frequently met with limited success, both because of interjurisdictional competition and because merchants and brokers could to some extent opt out of the formal system. The divergence in organizational form between Britain and other countries, brought about in part by Britain's Bubble Act of 1720, illustrates the potential for path-dependent institutional change. 1 Introduction Many market transactions are plagued by agency problems that give rise to a \fundamental problem of exchange" (Greif 2000), and in such cases markets can function only if suitable institutions enable transactors to overcome incentives for opportunism. Recent research has therefore studied the role of both formal public and private institutions in the organization and governance of markets (Dixit 2003). Some aspects of market governance institutions be- gin as \spontaneous" local orders or customs that may eventually \harden" into formal rules, while others are deliberately designed by entrepreneurs and lawmakers. \Good" institutions ∗Email: [email protected]. I am grateful to Anu Bradford, Stephen Haber, the editors, two anonymous referees, and participants in the October 2011 European University Institute conference on `Legal Order, the State, and Economic Development' for helpful comments and suggestions. -

Shipwreck Legislation and the Preservation of Submerged Artifacts Timothy J

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 22 | Issue 1 1990 Shipwreck Legislation and the Preservation of Submerged Artifacts Timothy J. Runyan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Timothy J. Runyan, Shipwreck Legislation and the Preservation of Submerged Artifacts, 22 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 31 (1990) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol22/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Shipwreck Legislation and the Preservation of Submerged Artifacts Timothy J. Runyan, Ph.D.* INTRODUCTION This article will examine the relationship of the law to a particular type of art: a submerged ship and its contents. Today, shipwrecks are a principal object of those archaeologists who seek to expand our knowl- edge of history through a study of submerged material culture.' Their enthusiasm for retrieving and preserving that culture has spawned the field of maritime or underwater archaeology. It has also spawned a de- bate over the ownership of submerged artifacts. An examination of mari- time or admiralty law and its relationship to shipwrecks forms the core of the first part of this Article and is followed by an analysis of the con- flict which has arisen between preservationists and commercial or trea- sure salvors. -

An Overview of Maritime Law Stephen M

The following document is offered to PBI faculty as a sample of good written materials. We are proud of the reputation of our “yellow books.” They are often the starting point in tackling a novel issue. From Boating Law and Liability PBI Course #7091 Published April 2012 An Overview of Maritime Law Stephen M. Calder, Esquire Copyright 2012 PBI and the author. All rights reserved. Preamble This overview is intended to be a general introduction to some of the issues that arise in cases governed by admiralty practice and maritime law, particularly in the federal courts. As is true in other practice areas, maritime law evolved over a considerable period of time, and continues to do so. Procedures for the handling of claims have been modified and refined in order to adapt to the changes that have occurred in our courts, as well as the relatively recent phenomenon of recreational boating on a large scale. Nevertheless, many fundamental principles have remained intact, such that maritime law is an unusual mix of ancient traditions and modern approaches to the resolution of disputes. The Source of Admiralty Law and Jurisdiction The family tree for the law governing boats and boating can be traced back to the Code of Hammurabi, the Egyptian and Phoenician merchant fleets, the Rhodian law that governed commerce in the Mediterranean, and later the Rolls of Oleron that recorded rules and customs applicable to the wine trade. It is said that Eleanor of Aquitaine and her son, Richard I, were responsible for the incorporation of the Rolls of Oleron into the laws of England, which eventually found their way into the maritime law of the United States. -

Glossary International Freight Terms

GLOSSARY INTERNATIONAL FREIGHT TERMS ABI - Automated Brokerage Interface: Is a system available to U.S. Customs Brokers with the computer capabilities and customs certification to transmit and exchange customs entries and other information, facilitating prompt release of imported cargo. Acceptance: A time draft (or bill of exchange) which the drawee has accepted and is unconditionally obligated to pay at maturity. Drawee's act in receiving a draft and thus entering into the obligation to pay its value at maturity. An agreement to purchase goods under specified terms. Add Hoc Charter: A one-off charter operated at the necessity of an airline or charterer. Ad Valorem ("according to the value"): A fixed percentage of the value of goods that is used to calculate customs duties and taxes. Admiralty Court: Is a court having jurisdiction over maritime questions pertaining to ocean transport, including contracts, charters, collisions, and cargo damages. Advance Against Documents: Load made on the security of the documents covering the shipment. Advising Bank: A bank that receives a letter of credit from an issuing bank, verifies its authenticity, and forwards the original letter of credit to the exporter without obligation to pay. Advisory Capacity: A term indicating that a shipper's agent or representative is not empowered to make definite decisions or adjustment without the approval of the group or individual represented. Affiliate: Is a company that controls, or is controlled by another company, or is one of two or more commonly controlled companies. Airfreightment: An agreement by a steamship line to provide cargo space on a vessel at a specified time and for a specified price to accommodate an exporter or importer, who then becomes liable for payment even though he is later unable to make the shipment. -

Canada's Admiralty Court in the Twentieth Century

Canada's Admiralty Court in the Twentieth Century Arthur J. Stone* The author outlines the debate surrounding the L'auteur traite du dabat ayant entour6 ]a creation creation of Canada's admiralty court. This debate was d'une Cour d'amiraut6 an Canada. Ce dtbat 6tait ali- fuelled by the desire for autonomy from England and ment6 par ]a volont6 d'une plus grande autonomie vis- the disagreement amongst Canadian politicians re- A-vis l'Angleterre, de meme que par le d~saccord entre garding which court was best suited to exercise admi- les politiciens canadiens quant A la cour la plus appro- ralty jurisdiction. In 1891, more than thirty years after pride pour avoir juridiction en mati~re de droit mari- this debate began, the Exchequer Court of Canada, a time. En 1891, apris plus de trente ans de dtbats, fut national admiralty court, was declared, replacing the crede la Cour de l'&chiquier du Canada, une cour unpopular British vice-admiralty courts. The jurisdic- d'amirantd nationale qui remplaga les impopulaires 2002 CanLIIDocs 40 tion of this court was generally consistent with the ex- cours britanniques de vice-amiraut6. La juridiction de isting English admiralty jurisdiction; it was not until cette cour 6tait gdndralement en accord avec la juridic- 1931 that Canada was able to decide the jurisdiction of tion des cours d'amirautd britanniques; il faflut attendre its own court. Since then, this jurisdiction has been en- 1931 pour que le Canada soit capable de d6cider de ]a larged by federal legislative measures, most notably the juridiction de ses propres tribunaux. -

Limitations on the Sieracki Doctrine Guy C

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 37 | Number 4 Article 5 6-1-1959 Admiralty -- Limitations on the Sieracki Doctrine Guy C. Evans Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Guy C. Evans, Admiralty -- Limitations on the Sieracki Doctrine, 37 N.C. L. Rev. 479 (1959). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol37/iss4/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES AND COMMENTS Admiralty-Limitations on the Sieracki Doctrine In Seas Shipping Co., Inc. v. Sierackil plaintiff-stevedore was in- jured while in the process of loading cargo into a ship. As a result, he subsequently sought to recover for his damages from the operator of the ship on the theory of unseaworthiness. 2 Theretofore the ship and her operator had been held liable to a seaman who was injured by reason of the unseaworthiness of the vessel.3 The Supreme Court held, how- ever, that liability for unseaworthiness was not limited to seamen but was available as well to persons who did a seaman's work irrespective of whether such persons were hired directly by the shipowner, through his consent, or by his arrangement. Doing a seaman's work was said to incur a seaman's risks for which a seaman would be entitled to a sea- worthy ship.