Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society Research Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Blood Service-Lancaster

From From Kendal Penrith 006) Slyne M6 A5105 Halton A6 Morecambe B5273 A683 Bare Bare Lane St Royal Lancaster Infirmary Morecambe St J34 Ashton Rd, Lancaster LA1 4RP Torrisholme Tel: 0152 489 6250 Morecambe West End A589 Fax: 0152 489 1196 Bay A589 Skerton A683 A1 Sandylands B5273 A1(M) Lancaster A65 A59 York Castle St M6 A56 Lancaster Blackpool Blackburn Leeds M62 Preston PRODUCED BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - BARTHOLOMEW(2 M65 Heysham M62 A683 See Inset A1 M61 M180 Heaton M6 Manchester M1 Aldcliffe Liverpool Heysham M60 Port Sheffield A588 e From the M6 Southbound n N Exit the motorway at junction 34 (signed Lancaster, u L Kirkby Lonsdale, Morecambe, Heysham and the A683). r Stodday A6 From the slip road follow all signs to Lancaster. l e Inset t K A6 a t v S in n i Keep in the left hand lane of the one way system. S a g n C R e S m r At third set of traffic lights follow road round to the e t a te u h n s Q r a left. u c h n T La After the car park on the right, the one way system t S bends to the left. A6 t n e Continue over the Lancaster Canal, then turn right at g e Ellel R the roundabout into the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (see d R fe inset). if S cl o d u l t M6 A h B5290 R From the M6 Northbound d Royal d Conder R Exit the motorway at junction 33 (signed Lancaster). -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

APPLY ONLINE the Closing Date for Applications Is Wednesday 15 January 2020

North · Lancaster and Morecambe · Wyre · Fylde Primary School Admissions in North Lancashire 2020 /21 This information should be read along with the main booklet “Primary School Admissions in Lancashire - Information for Parents 2020-21” APPLY ONLINE www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools The closing date for applications is Wednesday 15 January 2020 www.lancashire.gov.uk/schools This supplement provides details of Community, Voluntary Controlled, Voluntary Aided, Foundation and Academy Primary Schools in the Lancaster, Wyre and Fylde areas. The policy for admission to Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools is listed on page 2. For Voluntary Aided, Foundation Schools and Academies a summary of the admission policy is provided in this booklet under the entry for each school. Some schools may operate different admission arrangements and you are advised to contact individual schools direct for clarification and to obtain full details of their admission policies. These criteria will only be applied if the number of applicants exceeds the published admission number. A full version of the admission policy is available from the school and you should ensure you read the full policy before expressing a preference for the school. Similarly, you are advised to contact Primary Schools direct if you require details of their admissions policies. Admission numbers in The Fylde and North Lancaster districts may be subject to variation. Where the school has a nursery class, the number of nursery pupils is in addition to the number on roll. POLICIES ARE ACCURATE AT THE TIME OF PRINTING AND MAY BE SUBJECT TO CHANGE Definitions for Voluntary Aided and Foundation Schools and Academies for Admission Purposes The following terms used throughout this booklet are defined as follows, except where individual arrangements spell out a different definition. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report

Local Government fir1 Boundary Commission For England Report No. 52 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO.SZ LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund .Compton, GCB.KBE. DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin,QC. - MEMBERS The Countess Of Albemarle,'DBE. Mr T C Benfield. Professor Michael Chisholm. Sir Andrew Wheatley,CBE. Mr P B Young, CBE. To the Rt Hon Roy Jenkins, MP Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSAL FOR REVISED ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE CITY OF LANCASTER IN THE COUNTY OF LANCASHIRE 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for the City of Lancaster in . accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and of Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that City. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 60(1) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 13 May 197^ that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the Lancaster City Council, copies of which were circulated to the Lancashire County Council, Parish Councils and Parish Meetings in the district, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from any interested bodies, 3- Lancaster City Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representa- tion for our consideration. -

List of Delegated Planning Decisions

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL APPLICATION NO DETAILS DECISION 17/01219/OUT J Wedlake And Son, Wheatfield Street, Lancaster Outline Application Permitted application for the erection of a 2 storey and one 4 storey buildings comprising 12 apartments (C3) with associated access and relevant demolition of general industrial building (B2) and ancillary outbuildings for Mr R Smith (Castle Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00056/DIS Development Site, Bulk Road, Lancaster Discharge of Split Decision conditon 4 on approved application 17/01413/VCN for Eric Wright Construction (Bulk Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00110/DIS Land Adjacent To , Bulk Road, Lancaster Discharge of Split Decision condition 11 on approved application 17/01413/VCN for Stride Treglown (Bulk Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00112/DIS Development Site, Bulk Road, Lancaster Discharge of Split Decision conditions 2 and 5 on approved application 17/01413/VCN for Eric Wright Construction (Bulk Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00121/FUL Lancaster Girls Grammar School, Regent Street, Lancaster Application Permitted Erection of a two storey extension to create teaching block and creation of a new entrance to main building with single storey glazed link for Lancaster Girls Grammar School (Castle Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00122/LB Lancaster Girls Grammar School, Regent Street, Lancaster Application Permitted Listed building application for erection of a two storey extension to create teaching block, creation of a new entrance to main building with single storey glazed link and part demolition and rebuild of curtilage wall for Lancaster Girls Grammar School (Castle Ward 2015 Ward) 18/00136/DIS Development Site, Bulk Road, Lancaster Discharge of Split Decision condition 9 on approved application 17/01413/VCN for . -

Public Document Pack

Public Document Pack Committee: PLANNING AND HIGHWAYS REGULATORY COMMITTEE Date: MONDAY, 19TH DECEMBER 2005 Venue: MORECAMBE TOWN HALL Time: 10.30 A.M. A G E N D A 1 Apologies for Absence. 2 Minutes of the Meeting held on 14th November 2005 (circulated separately). 3 Items of Urgent Business authorised by the Chairman. 4 Declarations of Interest. Planning Applications for Decision Community Safety Implications In preparing the reports for this agenda, regard has been paid to the implications of the proposed developments on Community Safety issues. Where it is considered the proposed development has particular implications for Community Safety, this issue is fully considered within the main body of the report on that specific application. 5 A5 05/01276/FUL Ridgway Park, Lindeth Road, Silverdale (Pages 1 - 6) Silverdale Ward Erection of single-storey modular building, replacing existing portakabins for Ridgeway Children’s Services Ltd 6 A6 05/01156/CU 113 White Lund Road, Morecambe, Westgate (Pages 7 - 10) Lancashire Ward Change of use of land adjacent to site 8 park homes for gypsy residential accommodation for Mr D Walsh 7 A7 05/01148/FUL 15 Knowlys Drive, Heysham, Heysham (Pages 11 - Morecambe Central 16) Ward Application to retain windows and door in southern elevation, and erection of screen wall and fence, and access for disabled people for Mr and Mrs H G Maskrey 8 A8 05/00823/FUL Waterslack Garden Centre, Silverdale (Pages 17 - Waterslack Road, Silverdale Ward 20) Retrospective application for alterations to cafe and erection of -

Initial Template Document

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL APPLICATION NO DETAILS DECISION 15/01343/FUL Green Hill House Farm, Dunald Mill Lane, Nether Kellet Application Permitted Change of use of agricultural land adjacent to Greenhill House Farm for the siting of five eco-camping pods and facilities building, including landscaping and car park for Mr Ian Ward (Halton-with-Aughton Ward 2015 Ward) 15/01344/FUL 24 Salford Road, Galgate, Lancaster Demolition of existing Application Permitted side conservatory and garage and erection of a 3-bed dwelling with attached garage for Dr Alina Waite (Ellel Ward 2015 Ward) 15/01442/FUL Hare Hill, Smiths Barn And Corner House, Bay Horse Road, Application Permitted Ellel Retrospective application for the retention of three dwellinghouses for Mr Kevan Whittingham (Ellel Ward 2015 Ward) 15/01569/FUL Chapel House, Chapel Lane, Ellel Erection of a single storey Application Permitted side and rear extension, creation of a new access point and hard standing area to the front and side for Mr Peter Ballard (Ellel Ward 2015 Ward) 16/00013/FUL 34 Slyne Road, Morecambe, Lancashire Erection of a part Application Permitted single part two storey extension to the front and a two storey extension to the side for Mr & Mrs C. Parker (Torrisholme Ward 2015 Ward) 16/00050/DIS Tewitfields Trout Fishery, Burton Road, Warton Discharge of Initial Response Sent condition 7 and 14 on application 15/01011/FUL for Mr (Warton Ward 2015 Ward) 16/00059/VLA Far Lodge, Postern Gate Road, Quernmore Variation of the Application Refused Section 106 Agreement attached to application no. -

LANCASTER GIRLS' GRAMMAR SCHOOL ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS DETERMINED POLICY: SEPTEMBER 2022 Introduction Lancaster Girls' Gram

LANCASTER GIRLS’ GRAMMAR SCHOOL ADMISSION ARRANGEMENTS DETERMINED POLICY: SEPTEMBER 2022 Introduction Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School is a designated state funded, single sex grammar school which allocates places based on selective academic ability. The School is committed to prioritising places for girls within the city of Lancaster. Aims The aims of this document are: 1. to ensure compliance with The School Admissions Code February 2012 issued under Section 84 of the School Standards and Framework Act 1988. 2. to share the School's admission arrangements with parents, enabling them to easily understand how places at Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School are allocated. 3. to fairly, clearly and objectively identify and admit children to benefit from the education that the School offers. 2021 Admission Arrangements for the School Entry The School has two main points of entry: 11 plus and the Sixth Form. On occasion if there is a place available in the relevant Year group, the School will admit in Year, provided the applicant passes a mid-year test set by the School. Number of places The main School has 140 places available for September 2022 entry. The PAN for the Sixth Form is 95, and there are 200 places available in the Sixth Form. Sixth Form places will firstly be allocated to existing Year 11 pupils, who wish to continue their education in the School's Sixth Form. All remaining places will be offered to outside applicants up to the Sixth Form capacity of 200. 11 plus entry Applications are welcome for children born between 01/09/2010 and 31/08/2011 Early entry applicants Early entry applications from Year 7 applicants will be considered but evidence of exceptional academic ability in entrance testing will be required. -

Election of City Councillors for The

NOTICE OF POLL Lancaster City Council Election of City Councillors for the Bare Ward NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT: 1. A POLL for the ELECTION of CITY COUNCILLORS for the BARE WARD in the said LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL will be held on Thursday 2 May 2019, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. Three City Councillors are to be elected in the said Ward. 3. The surnames in alphabetical order and other names of all persons validly nominated as candidates at the above-mentioned election with their respective places of abode and descriptions, and the names of all persons signing their nomination papers, are as follows: 1. NAMES OF CANDIDATES 2. PLACES OF ABODE 3. DESCRIPTION 4. NAMES OF PERSONS SIGNING NOMINATION PAPERS (surname first) ANDERSON, Tony 33 Russell Drive, Morecambe, LA4 Morecambe Bay Independents Geoffrey Knight Sarah E Knight Glenys P Dennison Ray Stallwood Geoffrey T Nutt 6NR Deborah A Knight Roger T Dennison Shirley Burns Sandra Stallwood Pauline Nutt BARBER, Stephie Cathryn 7 Kensington Court, Bare Lane, Conservative Party Candidate Julia A Tamplin James F Waite James C Fletcher John Fletcher Robin Seward Bare, Morecambe, LA4 6DH Charles Edwards Christine Waite Angela J Fletcher David P Madden Kathleen H Seward BUCKLEY, Jonathan James (Address in Lancaster) The Green Party Chloe A G Buckley Jeremy C Procter Richard L Moriarty Michael C Stocks Philip G Lasan Georgina J M Sommerville Patricia E Salkeld Kathryn M Chandler Julia C Lasan Joseph L Moore EDWARDS, Charles 12 Ruskin Drive, Morecambe, LA4 Conservative Party Candidate -

FOB Gen Info 0708

FOB Gen Info 0708 11/8/08 10:30 AM Page 2 FOREST OF BOWLAND Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty B 6 5 44 4 er 5 e 2 7 K 6 Melling 9 r B i ve Map Key R 42742 Carnfortharrnfor CARNFO RT H StudfoldStudfdfold 35 Wennington nn A 6 1091 5 GressinghamGressinghss Low High Newby Bentham Bentham BB 6 26 5 2 4 5 4 Wennington Heritage sites Symbols Tathamat WharfeW Helwith 6 R Bridgee M i v Over Kelletet e ClaphamClapClaphClaClaaphamphph r W 1801 6 4B 8 6 0 4 8 e n B 1 Bleasdale Circle Nurserys n i ng BENTHAM R i B v 6 e 4 r 8 R R en n 0 i Hornby i v e r W i n AustwickAusA k b g b Bolton-le-SandsBoBoltoB ton-le-Sands l 2 Browsholme Hall Viewpoint Netherer Kellet ClaphamClaC e Aughton Wray Mill Houses StationSt 0 Feizor n e B 6 4 8 i v e r L u StainforthStainfonforth Ri v e r Hi n d b 3 Clitheroe Castle Garage Farleton u r 5 n A 5 1 0 5 R A Keasden 107070 6 4 Cromwell Bridge Pub Hestst Bank Lawkland R i v Claughton e r StackhouseStackh e 3 R B SlyneSlynynenee 8 o 6 5 Dalehead Church Birding Locations 6 e A 48 MORECAMBE A b Eldroth 6 0 HHaltoHaltonalton u 5 r Caton n Morecambe Burn A Lowgill Pier Head BareBa LaneLa A Moor LangclifLanangcliffe 6 Great Stone Café 6 B B B 5 402 2 Torrisholmeo rrisshoolo 34 7 44 7 Brookhouse Caton 2 7 5 7 Jubilee Tower Toilets 5 3 Moor B 68 GiggleswickGiggleeswickwickk A B Goodber Common SETTLESettleSetSe 5 3 2 Salter 8 Pendle Heritage Centre Tourist Information 1 GiggleswiGiggleswickeswickeswicwick 9 7 L ythe 4 StatioStatiStatStationionon 6 A Fell B BB5 2 57 3 5 9 Ribchester Roman Museum Parking HEYSHAMHEYSHE SHAM 8 9 Wham -

Lancashire Federation of Women's Institutes

LIST OF LANCASHIRE WIs 2021 Venue & Meeting date shown – please contact LFWI for contact details Membership number, formation year and month shown in brackets ACCRINGTON & DISTRICT (65) (2012) (Nov.) 2nd Wed., 7.30 p.m., Enfield Cricket Club, Dill Hall Lane, Accrington, BB5 4DQ, ANSDELL & FAIRHAVEN (83) (2005) (Oct.) 2nd Tues, 7.30 p.m. Fairhaven United Reformed Church, 22A Clifton Drive, Lytham St. Annes, FY8 1AX, www.ansdellwi.weebly.com APPLEY BRIDGE (59) (1950) (Oct.) 2nd Weds., 7.30 p.m., Appley Bridge Village Hall, Appley Lane North, Appley Bridge, WN6 9AQ www.facebook.com/appleybridgewi ARKHOLME & DISTRICT (24) (1952) (Nov.) 2nd Mon., 7.30 p.m. Arkholme Village Hall, Kirkby Lonsdale Road, Arkholme, Carnforth, LA6 1AT ASHTON ON RIBBLE (60) (1989) (Oct.) 2nd Tues., 1.30 p.m., St. Andrew’s Church Hall, Tulketh Road, Preston, PR2 1ES ASPULL & HAIGH (47) (1955) (Nov.) 2nd Mon., 7.30 p.m., St. Elizabeth's Parish Hall, Bolton Road, Aspull, Wigan, WN2 1PR ATHERTON (46) (1992) (Nov.) 2nd Thurs., 7.30 p.m., St. Richard’s Parish Centre, Jubilee Hall, Mayfield Street, Atherton, M46 0AQ AUGHTON (48) (1925) (Nov.) 3rd Tues., 7.30 p.m., ‘The Hut’, 42 Town Green Lane, Aughton, L39 6SF AUGHTON MOSS (19) (1955) (Nov.) 1st Thurs., 2.00 p.m., Christ Church Ministry Centre, Liverpool Road, Aughton BALDERSTONE & DISTRICT (42) (1919) (Nov.) 2nd Tues., 7.30 p.m., Mellor Brook Community Centre, 7 Whalley Road, Mellor Brook, BB2 7PR BANKS (51) (1952) (Nov.) 1st Thurs., 7.30 p.m., Meols Court Lounge, Schwartzman Drive, Banks, Southport, PR9 8BG BARE & DISTRICT (67) (2006) (Sept.) 3rd Thurs., 7.30 p.m., St. -

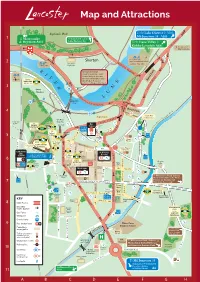

Map and Attractions

Map and Attractions 1 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree N.B. Greyhound Bridge closed for works Jan - Sept. Skerton Bridge to become two-way. Other trac routes also aected. Please see Retail Park www.lancashire.gov.uk for details 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R Escape H T Room R NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long 6 INFORMATION CENTRE Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis only Magistrates 8 Court Long Stay 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 11 AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Lancaster Leisure Park Peter Wade Guided Walks AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Wyresdale Road, Lancaster, LA1 3LA A series of interesting themed walks an eclectic mix of stalls. 01524 68444 around the district. Lancaster Castle lancasterleisurepark.com King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG 01524 420905 Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 - GB Antiques Centre visitlancaster.org.uk/whats-on/guided- thousand years of history. lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Open 10:00 – 17:00 walks-with-peter-wade/ Adults £1.50, Children/OAP 75p, Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 16:30 Under 5s Free Various dates, start time 2pm. 01524 64998 Closed all Bank Holidays Trade Dealers Free Tickets £3 lancastercastle.com - Lancaster Brewery Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily King Street Studios Monday-Thursday 10:00 - 17:00 Lune Aqueduct Open for guided tours 10:00 – 16:00 Exhibition space and gallery showing art Friday- Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 Take a Lancaster Canal Boat Cruise (some restrictions, please check with modern and contemporary values.