A Race Against Time for Kentucky's 2006 Watch Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAIN MAP HORSE INDUSTRY + URBAN DEVELOPMENT Aboutlexington LANDMARKS

MAIN MAP HORSE INDUSTRY + URBAN DEVELOPMENT ABOUTlexington LANDMARKS THE KENTUCKY HORSE PARK The Kentucky Horse Park is a 1,200 acre State Park and working horse farm that has been active since the 18th century. The park features approximately 50 breeds of horse and is the home to 2003 Derby Winner Funny Cide. The Park features tours, presentations, The International Museum of the Horse and the American Saddle Horse Museum as well as hosting a multitude of prestigious equine events. In the fall of 2010, the Kentucky Horse Park hosted the Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games, the first time the event has ever been held outside of Europe attracting and attendeance of over 500,000 people. The Park is also the location of the National Horse Center. that houses several equine management asso- ciations and breed organizations, The United States Equestrian Federation, The Kentucky Thoroughbred Association, The Pyramid Society, the American Hackney Horse Society, the American Hanoverian Soci- ety, U.S. Pony Clubs, Inc., among others. http://www.kyhorsepark.com/ image source: http://www.kyforward.com/tag/kentucky-horse-farms-white-fences/ MARY TODD LINCOLN’S HOME Located on Main Street in downtown Lexington, the Mary Todd Lincoln House was the family home of the future wife of Abraham Lincoln. Originally built as an inn, the property became the home of politician and businessman, Robert S. Todd in 1832. His daughter, Mary Todd, resided here until she moved to Spring- field, Illinois in 1839 to live with her elder sister. It was there that she met and married Abraham Lincoln, whom she brought to visit this home in the fall of 1847. -

Published By: the Kentucky Department of Aviation 90 Airport Rd

Published by: The Kentucky Department of Aviation 90 Airport Rd. Frankfort, KY 40601 Created and printed by The Division of Graphic Design and Printing PAID FOR WITH STATE FUNDS UNDER KRS57.375 AND PRINTED AS A PUBLIC SERVICE TO THE AVIATION COMMUNITY Update 05/02/2017 Commissioner Deputy Commissioner Steve Parker Todd X. Bloch Greater Commonwealth Aviation Division Sandra Huddleston Staff Assistant Joe Carter Airport Inspections - Administrative Branch Manager Craig Farmer Engineering Branch Manager Terry Hancock Administrative Specialists III Glen Anderson Engineer-Unmanned Aerial Systems Specialists Kelly Brown Internal Policy Analyst II Chip Barker Maintenance Worker I Sherri Bemis Administrative Specialist III Capital City Airport Division Scott Shannon Assistant Director David Gauss Airport Manager Sean Howard Pilot Danny Rogers Pilot Graeme Lang Pilot Serai Evans Flight Scheduler – Program Coordinator Steve Seger Chief of Aircraft Maintenance Shane Wilson Aircraft Mechanic/Inspector Morris Bryant Aircraft Mechanic/Inspector Tim Amyx Aircraft Mechanic/Inspector Jason Doss Aircraft Mechanic/Inspector Candi Scrogham Administrative Specialists III Troy Gaines Airport Operations Supervisor Jody Feldhaus Airport Flight Line Services David Lewis Airport Flight Line Services Mitchell Coldiron Airport Flight Line Services Darrell Sloan Airport Flight Line Services John Henry Airport Flight Line Services John Armstrong Airport Flight Line Services PHONE: 502-564-4480 FAX: 502-564-0173 KDA Website: http://transportation.ky.gov/Aviation/Pages/ -

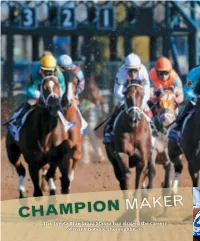

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

Pedigree Insights

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2019 WES CHAMPAGNE: FARRIER TO THE STARS PEDIGREE INSIGHTS: by Dan Ross FINAL CROP OF ARCH No foot, no horse--an adage that's as true now as when the world's first plough-horse was sidelined with a stone bruise. And IS ON THE MARCH while that same adage could be repurposed for almost any part of the horse's anatomy, it's the foot that bears the load. The hero's yoke. Of all the farriers around the nation's backstretches toiling away on those four surprisingly delicate parts of the racehorse, few have been as highly sought-after for as long as Wes Champagne. Nearly 40 years ago, Champagne was an exercise rider who, too big to follow in the boots of his jockey father, went to blacksmith school near Sacramento. Forty years later, he boasts a client list that started early on with Laz Barrera and never dipped in quality thereafter. Trainers like Charlie Whittingham, Bobby Frankel, Neil Drysdale, Richard Mandella, Bob Baffert, John Sadler. Horses like Tiffany Lass, Mister Frisky, Malek, Labeeb, Fusaichi Pegasus, Megahertz, Medaglia d'Oro, Game on Estihdaaf | Erika Rasmussen Dude. Cont. p5 by Andrew Caulfield IN TDN EUROPE TODAY The UAE 2000 Guineas, to my mind, has always been one of BRITISH RACING TO RESUME ON WEDNESDAY the most confusing races staged during the Dubai Racing British racing will resume on Wednesday after an equine influenza scare last week. Carnival. While this Group 3 contest is confined to 3-year-olds, it Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. -

96Th Running of the Toyota Blue Grass $1,000,000 (Grade

96th Running Of The Toyota Blue Grass $1,000,000 (Grade II) FOR THREE YEAR OLDS By subscription of $200 each on or before February 15, 2020 or $1,000 each on or before March 18, 2020. A Supplementary Nomination of $30,000 each may be made at time of entry (includes entry and starting fees). $5,000 to enter and an additional $5,000 to start, with $1,000,000 guaranteed, of which $600,000 to the owner of the winner plus 100 Road To The Kentucky Derby Points, $200,000 to second plus 40 Road To The Kentucky Derby Points, $100,000 to third plus 20 Road To The Kentucky Derby Points, $50,000 to fourth plus 10 Road To The Kentucky Derby Points, $30,000 to fifth and $20,000 to be divided equally among sixth through last. Weight: 123 lbs. The maximum number of starters for the Toyota Blue Grass will be limited to fourteen with two also eligible. In the event that more than fourteen pass the entry box, the fourteen starters will be determined at that time with preference given to graded stakes winners (in order I-II-III), then highest earnings. Starters to be named through the entry box by the usual time of closing. Keeneland will present a trophy cup to the winning owner. NINE FURLONGS TO BE RUN SATURDAY, APRIL 4, 2020 *********************************** AJAAWEED b.c.3 Shadwell Stable Kiaran P. McLaughlin AJHAR gr/ro.c.3 Shadwell Stable Kiaran P. McLaughlin ALPHA SIXTY SIX b.c.3 Paul P. Pompa, Jr. -

GREGORY A. LUHAN, AIA, RA, NCARB Associate Dean for Research

GREGORY A. LUHAN, AIA, RA, NCARB Associate Dean for Research e-mail: [email protected] http://www.uky.edu/design/index.php/faculty/portfolios/107 http://luhanstudio.net Studio: 3316 Braemer Drive, Lexington, Kentucky 40502-3376 studio: 859.492.5942 EDUCATION: Texas A&M University Dates Attended: 2013-present Major: Architecture Degree Track: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD in Architecture, expected 2016) W. W. Caudill Endowed Graduate Student Research Fellowship in Architecture (2013-present) Princeton University Dates Attended: 1996-1998 Major: Architecture Degree Received: Master of Architecture (1998) Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Dates Attended: 1986-1991 Major: Architecture Degree Received: Bachelor of Architecture (1991) Professional Extern Program State University of New York/Rockland Dates Attended: 1985-1986 Major: Philosophy, Engineering -- Honors Mentor/Talented Student (M/TS) Honors Program Phi Sigma Omicron Honor Society PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Academic Positions Held: 1. University of Kentucky Primary Appointment College of Design, School of Architecture, Pence Hall, Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0041 Associate Dean for Research, College of Design, July 2007-present John Russell Groves Kentucky Housing Corporation Research Professorship, 2007-2008 Associate Professor of Architecture (with Tenure), May 2006–present Assistant Professor of Architecture, July 2000-May 2006 Adjunct Professor, August 1998-June 2000 Secondary Appointments Faculty Full Member of the Graduate School, Architecture, 2007-present Faculty Full Member of the Graduate School, Historic Preservation, 2007-present Faculty Associate Member, VisCenter & Virtual Environments, 2005-present Faculty Associate Member, Center for Appalachian Studies, 2003-present Faculty Associate Member of the Graduate School, Architecture, 2003-2007 Faculty Associate Member of the Graduate School, Historic Preservation, 2002-2007 gregory a. -

146Th Running of Triple Crown 146Th Kentucky Derby

146th Running Of Triple Crown 146th Kentucky Derby - 145th Preakness Stakes - 152nd Belmont Stakes $3,000,000 (Grade I) 146TH RUNNING OF THE KENTUCKY DERBY TO BE RUN SATURDAY, MAY 2ND, 2020, 145TH RUNNING OF THE PREAKNESS STAKES TO BE RUN SATURDAY, MAY 16TH, 2020 AND 152ND RUNNING OF THE BELMONT STAKES TO BE RUN SATURDAY JUNE 6TH, 2020 ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER TO BE RUN SATURDAY, MAY 2, 2020 *********************************** (17)FASHION STORM ch.c.3 Diamond A Racing Corp. Richard E. Mandella AIRSTREEM gr/ro.c.3 Jackpot Farm and Dede McGehee Steven M. Asmussen AJAAWEED b.c.3 Shadwell Stable Kiaran P. McLaughlin ALL EYES WEST b.c.3 Gary and Mary West Jason Servis ALPHA SIXTY SIX b.c.3 Paul P. Pompa, Jr. Todd A. Pletcher AMEN CORNER b.c.3 Howling Pigeons Farm, LLC Jeremiah O'Dwyer AMERICAN BABY (JPN) dk b/.c.3 Katsumi Yoshizawa Yasushi Shono AMERICAN BUTTERFLY b.c.3 Les Wagner D. Wayne Lukas AMERICAN CODE b.c.3 Byerley Racing, LLC Bob Baffert AMERICAN FACE ch.c.3 Katsumi Yoshizawa Hirofumi Toda AMERICAN SEED b.c.3 Katsumi Yoshizawa Kenichi Fujioka AMERICAN THEOREM gr/ro.r.3 Kretz Racing, LLC George Papaprodromou AMERICANUS b.c.3 Courtlandt Farms Mark A. Hennig ANCIENT LAND dk b/.g.3 Martin Riley, D. Carroll, C. Scott and J. Howard Casey T. Lambert ANCIENT WARRIOR b.c.3 Al Graziani Jerry Hollendorfer ANNEAU D'OR b.c.3 Peter Redekop B. C., Ltd. Blaine D. Wright ANSWER IN b.g.3 Robert V. -

Owners, Kentucky Derby (1875-2017)

OWNERS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2017) Most Wins Owner Derby Span Sts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Calumet Farm 1935-2017 25 8 4 1 Whirlaway (1941), Pensive (’44), Citation (’48), Ponder (’49), Hill Gail (’52), Iron Liege (’57), Tim Tam (’58) & Forward Pass (’68) Col. E.R. Bradley 1920-1945 28 4 4 1 Behave Yourself (1921), Bubbling Over (’26), Burgoo King (’32) & Brokers Tip (’33) Belair Stud 1930-1955 8 3 1 0 Gallant Fox (1930), Omaha (’35) & Johnstown (’39) Bashford Manor Stable 1891-1912 11 2 2 1 Azra (1892) & Sir Huon (1906) Harry Payne Whitney 1915-1927 19 2 1 1 Regret (1915) & Whiskery (’27) Greentree Stable 1922-1981 19 2 2 1 Twenty Grand (1931) & Shut Out (’42) Mrs. John D. Hertz 1923-1943 3 2 0 0 Reigh Count (1928) & Count Fleet (’43) King Ranch 1941-1951 5 2 0 0 Assault (1946) & Middleground (’50) Darby Dan Farm 1963-1985 7 2 0 1 Chateaugay (1963) & Proud Clarion (’67) Meadow Stable 1950-1973 4 2 1 1 Riva Ridge (1972) & Secretariat (’73) Arthur B. Hancock III 1981-1999 6 2 2 0 Gato Del Sol (1982) & Sunday Silence (’89) William J. “Bill” Condren 1991-1995 4 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Joseph M. “Joe” Cornacchia 1991-1996 3 2 0 0 Strike the Gold (1991) & Go for Gin (’94) Robert & Beverly Lewis 1995-2006 9 2 0 1 Silver Charm (1997) & Charismatic (’99) J. Paul Reddam 2003-2017 7 2 0 0 I’ll Have Another (2012) & Nyquist (’16) Most Starts Owner Derby Span Sts. -

The Blue Grass Trust for Historic Preservation Annual Awards 2020

THE BLUE GRASS TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION ANNUAL AWARDS 2020 PRESERVATION CRAFTSMAN AWARD Given to a building industry craftsman who has exhibited a strong commitment to quality craftsmanship for historic buildings. GRANT LOGAN COPPER COPPER STEEPLE RESTORATION 1ST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH Grant Logan Copper specializes in custom copper and sheet-metal fabrication on both new and historic buildings. Grant Logan, of Nicholasville, re-clad the steeple on First Presbyterian Church with copper sheeting. The historic church at 174 North Mill was built in 1872 by prominent local architect Cincinnatus Shryock and is listed on the Na- tional Register of Historic Places. Each piece of copper on the steeple had to be measured, shaped and cut by hand. Adding to the chal- lenge, work to remove the old metal sheeting, repair the wooden structure of the steeple, and then attach the new copper had to be done from a lift. As work neared the top of the 175 foot steeple, the lift was not tall enough to reach the top. Grant and his workmen had to build a ladder and attach it to the steeple to finish the last 15 feet. PUBLIC SERVICE TO PRESERVATION AWARD Given to a government agency or official for service to preservation movement or to a specific project. PURCHASE OF DEVELOPMENT RIGHTS PROGRAM- LFUCG The Lexington Fayette Urban County Gov- ernment’s Purchase of Development Rights (PDR) Program is turning twenty this year. The programs mission is to preserve central Kentucky’s farmland by preventing future development from occurring on participat- ing properties. In addition to protecting our natural resources, it also is a friend of historic preservation by encouraging owners to pre- serve and maintain historic aspects of their farmland, such as stone fences and outbuild- ings. -

2018 Media Guide NYRA.Com 1 FIRST RUNNING the First Running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park Took Place on a Thursday

2018 Media Guide NYRA.com 1 FIRST RUNNING The first running of the Belmont Stakes in 1867 at Jerome Park took place on a Thursday. The race was 1 5/8 miles long and the conditions included “$200 each; half forfeit, and $1,500-added. The second to receive $300, and an English racing saddle, made by Merry, of St. James TABLE OF Street, London, to be presented by Mr. Duncan.” OLDEST TRIPLE CROWN EVENT CONTENTS The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is the oldest of the Triple Crown events. It predates the Preakness Stakes (first run in 1873) by six years and the Kentucky Derby (first run in 1875) by eight. Aristides, the winner of the first Kentucky Derby, ran second in the 1875 Belmont behind winner Calvin. RECORDS AND TRADITIONS . 4 Preakness-Belmont Double . 9 FOURTH OLDEST IN NORTH AMERICA Oldest Triple Crown Race and Other Historical Events. 4 Belmont Stakes Tripped Up 19 Who Tried for Triple Crown . 9 The Belmont Stakes, first run in 1867, is one of the oldest stakes races in North America. The Phoenix Stakes at Keeneland was Lowest/Highest Purses . .4 How Kentucky Derby/Preakness Winners Ran in the Belmont. .10 first run in 1831, the Queens Plate in Canada had its inaugural in 1860, and the Travers started at Saratoga in 1864. However, the Belmont, Smallest Winning Margins . 5 RUNNERS . .11 which will be run for the 150th time in 2018, is third to the Phoenix (166th running in 2018) and Queen’s Plate (159th running in 2018) in Largest Winning Margins . -

![Jockey Silks[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9845/jockey-silks-2-1349845.webp)

Jockey Silks[2]

RACING SILKS A MULTI- DISCIPLINARY LESSON ON DESIGN FOR K – 12TH WHAT ARE RACING SILKS? Silks are the uniform that a jockey wears during a race. The colorful jackets help the race commentator and the fans identify the horses on the track. WHO DECIDES WHAT THE SILKS LOOK LIKE? • The horse owner designs the silks. • Jockeys change their silks each race to reflect the owner of the horse they will be riding. • When you see two of the same silks in one race, that means that both of the horses belong to the same owner. • Each silks design is registered with the Jockey Club so that no two owners have the same silks. This ensures that each design is unique. A FEW JOCKEY CLUB DESIGN RULES • It costs $100 per year to register your silks. You must renew the registration annually. Colors are renewable on December 31st of the year they are registered. • Front and back of silks must be identical, except for the seam design. • Navy blue is NOT an available color. • A maximum of two colors is allowed on the jacket and two on the sleeves for a maximum of four colors. • You may have an acceptable emblem or up to three initials on the ball, yoke, circle or braces design. You may have one initial on the opposite shoulder of the sash, box frame or diamond design. COLORS AND PATTERNS Silks can be made up of a wide variety of colors and shapes, with patterns like circles, stars, squares, and triangles. We know colors and patterns mean things, and sometimes horse owners draw inspirations for their design from their childhood, surroundings, favorite things, and careers. -

Kentucky Derby

The Legacy and Traditions of Churchill Downs and the Kentucky Derby The Kentucky Derby The Kentucky Derby has taken place annually in Louis- ville, Kentucky since 1875. It was started by Meriwether Lewis Clark, Jr. at his track he called Churchill Downs, and it has run continuously since that first race. This first jewel of the Triple Crown has produced famous winners, with thirteen of these winners gaining that Triple Crown title. Lewis limited the Derby to only 3-year old horses. The race has evolved and grown over time and has changed since its first running, remaining an important event for more than a century. Through the study of the Derby’s influential historic traditions, notable winners and horse farms in Kentucky, and its profound cultural TABLE OF CONTENTS impact, this program will identify and explore these dif- Background and History…..2 ferent aspects that all contribute to the excitement and legacy of the “most exciting two minutes in sports.” Curriculum Standards…..3 Traditions ................ 4-8 Triple Crown ............ 9 Derby Winners ........ 10-11 Notable Horse Farms….12-13 Significant Figures…...15 Bibliography………….16 Image list…………….17-18 Derby Activities…….19-22 To replicate the races he witnessed in Europe, Meri- wether Lewis Clark Jr., the grandson of explorer Wil- liam Clark, created three races in the United States that resembled those he’d attended in Europe. The first meet was in May of 1875. Family ties to the horse racing world led Clark to his purchase of what would become Churchill Downs, named after his uncles, John and Henry Churchill in 1883.