Zara: Fast Fashion from Savvy Systems”, Chapter 3 from the Book Getting the Most out of Information Systems (Index.Html) (V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World's Richest Get $182 Billion Poorer

World’s Richest Get $182 Billion Poorer 12/29/15, 3:34 PM World’s Richest Get $182 Billion Poorer By: DailyForex.com They say the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. But in 2015, it was the world’s richest that got poorer, losing a walloping $182 billion this past week alone. The world’s 400 richest people reacted to weak manufacturing data from China and the retreat in commodities which sent global markets plunging. According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index which measures the world’s wealthiest people based on market and economic changes, falling commodities prices and signs of a slower- growing China scared investors around the world and are to be blame for the first annual decline for the daily wealth index since it debuted in 2012 and the biggest weekly drop since the expanded tracking list began in September 2014. The Bloomberg Billionaires Index is a group that includes Warren Buffett and Glencore Plc’s Ivan Glasenberg and the combined net worth of the index members fell by $76 billion on Friday alone, when the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of U.S. stocks ended its worst week since 2011. The collapse in oil prices, which has seen its longest weekly losing streak since 1986 amid signs of an extended supply glut, contributed to $15.2 billion in losses for the world’s wealthiest energy billionaires. Continental Resources Inc. Chairman Harold Hamm saw $895 million, or 9 percent of his net worth, vanish in a week. Change of Places According to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index…. -

4607 Stores 11084 Millions Of

4,607 stores millions of 11,084 euros in sales countries with 74 sales presence 92,301 employees nnual A Report 2009 Global Reporting 6 Initiative Indicators Letter from the 14 Chairman Inditex business 16 model 18 53 54 163 IP Inditex Performance IC Inditex Commitment Summary of 2009 Customers, shareholders 20 financial year 56 and society Milestones Corporate Social 26 for the year 66 Responsibility Commercial Human 28 concepts 124 Resources International Environmental 46 presence 136 dimension 4 Inditex Annual Report 2009 164 309 LD Legal Documentation Economic and financial 167 report Corporate governance 233 report Activities Report 296 Audit and Control Committee Activities Report Nomination 303 And Remuneration Committee Verification of the audit of 308 GRI indicators 5 lobal G Reporting Initiative Indicators With transparency as the fundamental principle in its relationship with society, Inditex has followed the Global Reporting Initiative indicators since it published its first Sustainability Report in 2002. Using this guide, Inditex attempts to provide detailed, organised access to the infor- mation on its activity to all its stakeholders. Within the general indicators, specific indicators for the textile and footwear sector have been included, identified in the following way: Specific indicator for the sector Specific indicator comment for the sector 6 Inditex Annual Report 2009 Pages 1. STRATEGY AND ANALYSIS 14-15 1.1 Statement from the most senior decision-maker about the relevance of sustainability to the organisation and its strategy. 267-273, 1.2 Description of key impacts, risks, and opportunities. 20-25 Apparel and Footwear Sector Specific Commentary: Where applicable, this should include an assessment of supply chain performance. -

Top 10 Billionaires of the World

TOP 10 BILLIONAIRES OF THE WORLD 16 JAN 2018 Top 10 billionaires of the world according to Bloomberg Billionaires Index as on January 10 2018. 1. 6. Jeff Bezos | Net worth - USD 106 billion | Amazon CEO Carlos Slim | Net worth - USD 64 billion | Mexican and founder Jeff Bezos is the largest shareholder of the billionaire and controller of the Telco American Movil firm. He recorded a net worth of USD 90 billion in October Carlos Slim has holdings in banking and mining in Latin last year. America. He is also interested in investing in construction businesses. 2. Bill Gates | Net worth - USD 93.3 billion | Microsoft co- 7. founder Bill Gates continues to be a part of the rich list. He Bernard Arnault | Net worth - USD 62.4 billion | French has been a part of the list since 1987, where, most times he Businessman Bernard Arnault is the chairman of LVMH has been ranked the richest in the world. Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton. It is currently the largest luxury goods maker. 3. Warren Buffett| Net worth - USD 87.3 billion| CEO and 8. largest shareholder of Berkshire Hathaway Warren Buffett Larry Page | Net worth - USD 55 billion | Larry Page is continues to be one of the richest in the world. The firm has the CEO and co-founder of Alphabet, the holding stakes in Coca-Cola, American Express and Wells Fargo, company of Google - the world's largest search engine. among other profit-making firms. 9. 4. Larry Ellison | Net worth - USD 54.7 billion | Larry Mark Zuckerberg | Net worth - USD 77.3 billion | Facebook Ellison is the founder and largest shareholder of Oracle, co-founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg owns the largest one of the largest database companies in the world. -

Amancio Ortega Se Convierte En El Hombre Más Rico De España

NIVEL B REVISTA DE LA CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN EN REINO UNIDO E IRLANDA enero 2013 Autor: Ramón Porto Prado Profesor de Bullers Wood School, Londres NIPO: 030-13-043-X Amancio ortega se convierte en el hombre más rico de Europa Dos de los establecimientos de la empresa de A. ortega Foto: r. Porto La revista Forbes ha situado a ortega como el tercer hombre más rico del planeta. TEXTO En un momento en el que España sufre una de Parece sorprendente que en medio de una crisis las mayores crisis económicas desde la guerra civil, tan dura como la actual, sus acciones en bolsa se el español Amancio Ortega, dueño de la cadena hayan disparado un 43% desde que comenzaron de tiendas de moda Zara, se convierte en la pri- a cotizarse en 2012 y sus beneficios en el primer mera fortuna europea, estimada en 38.000 millones trimestre del año sean un 30% superiores a los del de euros, por delante del sueco Ingvar Kamprad, mismo periodo del año pasado, lo que supone un dueño de la cadena de tiendas de muebles y com- resultado récord. plementos para el hogar Ikea y del francés Bernard Este ascenso meteórico se debe a un conjunto Arnault, propietario de la firma de artículos de lujo de estrategias de mercado exitosas. No cabe duda Louis Vuiton Moët Hennessy. alguna que los mercados emergentes de Asia y es- La revista Forbes, publicación americana espe- pecialmente de China son en gran medida la causa cializada en el mundo de los negocios, edita cada de este éxito imparable. -

Zara Case: Fast Fashion from Savvy Systems a Gallaugher.Com Case Provided Free to Faculty & Students for Non-Commercial Use © Copyright 1997-2008, John M

Zara Case: Fast Fashion from Savvy Systems a gallaugher.com case provided free to faculty & students for non-commercial use © Copyright 1997-2008, John M. Gallaugher, Ph.D. – for more info see: http://www.gallaugher.com/chapters Last modified: Sept. 13, 2008 Note: this is an earlier version of the case. All cases updated after July 2009 are now hosted (and still free) at http://www.flatworldknowledge.com. For details see the ‘Courseware’ section of http://gallaugher.com INTRODUCTION The poor, ship-building town of La Coruña in northern Spain seems an unlikely home to a tech- charged innovator in the decidedly ungeeky fashion industry, but that’s where you’ll find “The Cube”, the gleaming, futuristic central command of the Inditex Corporation (Industrias de Diseno Textil), parent of game-changing clothes giant, Zara. The blend of technology-enabled strategy that Zara has unleashed seems to break all of the rules in the fashion industry. The firm shuns advertising, rarely runs sales, and in an industry where nearly every major player outsources manufacturing to low-cost countries, Zara is highly vertically integrated, keeping huge swaths of its production process in-house. These counterintuitive moves are part of a recipe for success that’s beating the pants off the competition, and it has turned the founder of Inditex, Amancio Ortega, into Spain’s wealthiest man and the world’s richest fashion executive. Zara’s operations are concentrated in La Coruña and Zaragoza, Spain. A sampling of the firm’s designs, and “The Cube”, as shown on the firm’s websites. The firm tripled in size between 1996 and 2000, then skyrocketed from $2.43 billion in 2001 to $13.6 billion in 2007. -

Top 100 Billionaires

Top 100 Billionaires Name Net Worth Age Source Country of Citizenship Bill Gates 86 61 Microsoft United States Warren Buffett 75.6 87 Berkshire Hathaway United States Jeff Bezos 72.8 53 Amazon.com United States Amancio Ortega 71.3 81 Zara Spain Mark Zuckerberg 56 33 Facebook United States Carlos Slim Helu 54.5 77 telecom Mexico Larry Ellison 52.2 73 software United States David Koch 48.3 77 diversified United States Charles Koch 48.3 81 diversified United States Michael Bloomberg 47.5 75 Bloomberg LP United States Bernard Arnault 41.5 68 LVMH France Larry Page 40.7 44 Google United States Sergey Brin 39.8 44 Google United States Liliane Bettencourt 39.5 94 L'Oreal France S. Robson Walton 34.1 72 Wal-Mart United States Jim Walton 34 69 Wal-Mart United States Alice Walton 33.8 67 Wal-Mart United States Wang Jianlin 31.3 62 real estate China Li Ka-shing 31.2 89 diversified Hong Kong Sheldon Adelson 30.4 84 casinos United States Steve Ballmer 30 61 Microsoft United States Jorge Paulo Lemann 29.2 78 beer Brazil Jack Ma 28.3 53 e-commerce China David Thomson 27.2 60 media Canada Beate Heister & Karl Albrecht Jr. 27.2 - supermarkets Germany Jacqueline Mars 27 77 candy United States John Mars 27 81 candy United States Phil Knight 26.2 79 Nike United States George Soros 25.2 87 hedge funds United States Maria Franca Fissolo 25.2 82 Nutella, chocolates Italy Ma Huateng 24.9 45 internet media China Lee Shau Kee 24.4 89 real estate Hong Kong Mukesh Ambani 23.2 60 petrochemicals, oil & gas India Masayoshi Son 21.2 60 internet, telecom Japan Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen 21.1 69 Lego Denmark Georg Schaeffler 20.7 52 automotive Germany Joseph Safra 20.5 78 banking Brazil Susanne Klatten 20.4 55 BMW, pharmaceuticals Germany Michael Dell 20.4 52 Dell computers United States Laurene Powell Jobs 20 53 Apple, Disney United States Len Blavatnik 20 60 diversified United States Paul Allen 19.9 64 Microsoft, investments United States Stefan Persson 19.6 69 H&M Sweden Theo Albrecht, Jr. -

Forbes 2017 Billionaires List: Meet the Richest People on the Planet

Forbes 2017 Billionaires List: Meet The Richest People On The Planet forbes.com/sites/kerryadolan/2017/03/20/forbes-2017-billionaires-list-meet-the-richest-people-on-the-planet/ 3/19/2017 By Luisa Kroll and Kerry A. Dolan It was a record year for the richest people on earth, as the number of billionaires jumped 13% to 2,043 from 1,810 last year, the first time ever that Forbes has pinned down more than 2,000 ten-figure-fortunes. Their total net worth rose by 18% to $7.67 trillion, also a record. The change in the number of billionaires -- up 233 since the 2016 list -- was the biggest in the 31 years that Forbes has been tracking billionaires globally. Gainers since last year’s list outnumbered losers by more than three to one. Read more: The Full List of The World's Billionaires Bill Gates is the number one richest for the fourth year in a row, and the richest person in the world for 18 out of the past 23 years. He has a fortune of $86 billion, up from $75 billion last year. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos had the best year of any person on the planet, adding $27.6 billion to his fortune; now worth $72.8 billion, he moved into the top three in the world for the first time, up from number five a year ago. Warren Buffett had the second-best year, and the biggest gain since Donald Trump was elected president in November 2016. His $14.8 billion jump in 12 months was enough for him to grab back the number two spot from Amancio Ortega, founder of Spanish clothing chain Zara. -

Billionaires for the Second World's Billionaires Time in History

www.BreakingNewsEnglish.com - The Mini Lesson Asia has most of the True / False a) Asia has the most billionaires for the second world's billionaires time in history. T / F 3rd March, 2013 b) Asia has over 100 more billionaires than the USA. T / F A newly-published c) There are more billionaires in Moscow than in report on global any other capital city. T / F wealth says that for the first time, Asia d) The richest person in the world is from has more dollar Mexico. T / F billionaires than the e) The report author thinks he only found around USA. According to a third of all billionaires. T / F the Global Rich List 2013 from the f) The author thinks the number of Chinese research institute Hurun, there were 1,453 people billionaires will start to fall. T / F whose personal worth was $1 billion or more at g) Chinese entrepreneurs are not getting ready the end of January. Asia had 608 billionaires, to globalize. T / F compared with 440 in the USA and 324 in Europe. Moscow came top of the list of billionaire capitals h) Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg isn't the world's of the world with 76 of the world's mega-rich; youngest billionaire. T / F New York, Hong Kong, Beijing and London followed. The world's wealthiest person is Mexican telecom tycoon Carlos Slim, who has $66 billion. Synonym Match He is followed by US investor Warren Buffett and 1. wealth a. originator Amancio Ortega, boss of the fashion brand Zara. 2 according to b. -

Bloomberg Billionaires Index Order Now, Wear It Tomorrow

Bloomberg the Company & Its Products Bloomberg Anywhere Remote Login Bloomberg Terminal Demo Request Bloomberg Menu Search Sign In Subscribe Bloomberg Billionaires Index Order now, wear it tomorrow. That's next day View profiles for each of the world’s 50de0livery for you* richest people, see the biggest movers, and compare fortunes or track returns. As of July 18, 2018 The Bloomberg Billionaires Index is a daily ranking of the world’s richest people. Details about the calculations are provided in the net worth analysis on each billionaire’s profile page. The figures are updated at the close of every trading day in New York. Rank Name Total net worth $ Last change $ YTD change Country Industry 1 Jeff Bezos $152B +$1.69B +$53.2B United States Technology 2 Bill Gates $95.3B +$5.13M +$3.54B United States Technology 3 Mark Zuckerberg $83.8B +$967M +$11.0B United States Technology 4 Warren Buffett $79.2B -$3.82B -$6.14B United States Diversified 5 Bernard Arnault $75.0B +$252M +$11.7B France Consumer 6 Amancio Ortega $74.9B +$78.3M -$427M Spain Retail 7 Carlos Slim $62.7B -$382M +$1.19B Mexico Diversified 8 Larry Page $58.4B +$630M +$5.98B United States Technology 9 Sergey Brin $56.9B +$608M +$5.78B United States Technology 10 Larry Ellison $55.2B +$359M +$2.12B United States Technology Francoise Bettencourt 11 Meyers $49.2B +$14.1M +$4.73B France Consumer 12 Charles Koch $46.9B +$247M -$1.27B United States Industrial 13 David Koch $46.9B +$247M -$1.27B United States Industrial 14 Jack Ma $44.4B +$317M -$1.08B China Technology 15 Mukesh Ambani $44.0B -

Amancio Ortega, a Leader in the Shade

La Dirección Estratégica de la Empresa. Teoría y Aplicaciones L.A. Guerras & J.E. Navas Thomson Reuters-Civitas, 2007, 4th edition www.guerrasynavas.com AMANCIO ORTEGA, A LEADER IN THE SHADE Ana Farto Muñoz Miriam Delgado Verde Universidad Complutense de Madrid Currently, many managers pay more attention to image than product and daily management. On the contrary, a leader in the shade is someone who flees of any prominence, managing in silence and in a discreet way. That is, the anonymity is preferred before appearing in the mass media. In this sense, a reliable, careful and confidential management is chosen, but also effective. Thus, a good example of that kind of leader is Amancio Ortega, the leader of Inditex business group. In 2009, he became 73 years old and owning 60% of the stakes at Inditex group. Moreover, he is the richest man in Spain –his personal fortune is 18,300 million euros-, occupying the position 10 in the list of international multimillionaires published by Forbes magazine. There are a few data regarding his private life, just he lives in a duplex located in A Coruña and he has lunch with his employees during the week in the firm’s collective dining room in Arteixo. He never wears ties, he rarely misses a football match of Deportivo de La Coruña team, and his private aeroplane -36 million of euros- and Casas Novas riding centre –where he plays horse-riding, his passion- are the only known luxuries. Silently and without big rejoicing, the conquest of Milan –the capital of Italian fashion- has been included in the list of Amancio Ortega’s successes. -

The World's Richest: How Do They Compare?

18th September 2017 The World’s Richest: How Do They Compare? Discover the world’s richest people, their traits and how they compare over the past decade. The world’s richest people have worked tirelessly to reach their current status, but how do they compare to each other? Home, motor and life insurance provider Budget Insurance has uncovered a wealth of stats and facts about the richest people in 2007 and 2017 in its latest discovery piece: ‘The World’s Richest: How Do They Compare?’ The innovative tool pits the likes of Bill Gates against Mark Zuckerberg to see how the top tycoons measure up. It reveals a number of statistics that show how the current ten richest people in the world compare to those from a decade ago. The piece also uncovers how the world’s richest people stack up against each other when it comes to individual characteristics like age, height and country of origin. 2007 VS 2017 Markets and industries can shift in a matter of seconds, so it can be hard to keep up to speed. Budget Insurance compared a number of interesting facts about the world’s richest people in 2007 and 2017. The results show that despite 33-year-old Mark Zuckerberg’s arrival in the top ten rich list, the average age of these tycoons has gone up from 66 to 69.1 The average net worth of those in the top ten has increased by 78% from $34.40 billion in 2007 to $61.28 billion in 2017, despite the 2008 global crash.2 From cars and net worth to charitable donations and private jets, the world’s most affluent certainly have plenty to think about in terms of safeguarding their health, wealth, family and property. -

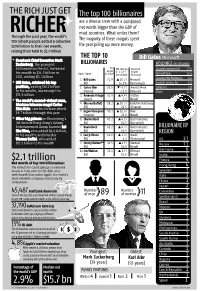

RICHER Most Countries

THE RICH JUST GET The top 100 billionaires are a diverse crew with a combined net worth bigger than the GDP of RICHER most countries. What unites them? Through the past year, the world’s The majority of these moguls spent 100 richest people added a collective $200 billion to their net wealth, the year piling up more money. raising their total to $2.1 trillion THE TOP 10 Bill Gates Microsoft | Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg, the youngest BILLIONAIRES HOLDINGS (IN $ BILLION) billionaire on the list, increased Net YTD change, Source of Cascade InvestmentLLC 37.6 his wealth to $24.5 billion in worth, in $ bn* / wealth Rank Name in $ bn* percentage (Industry) MicrosoftCorp. 12.6 2013, adding $12.3 billion Canadian Nat.Railway Co. 4.4 1 Bill Gates 72.9 !10.2 / Microsoft | Bill Gates, retained his top (US) 16.2% (Technology) Republic Services Inc. 3.0 position, adding $10.2 billion 2 Carlos Slim 65.5 "-9.7 / America Movil Ecolab Inc. 2.8 to his wealth, increasing it to (Mexico) -12.9 (Telecom) Others 12.5 $72.9 billion 3 Amancio Ortega 61.9 !4.4 / Inditex | The world’s second-richest man, (Spain) 7.7 (Retail) Mexican telecom mogul Carlos 4 Warren Buffett 58.2 !10.3 / Berkshire Hathaway Slim Helu, saw his fortune shrink (US) 21.5 (Finance) $9.7 billion through this year 5 Ingvar Kamprad 50.3 !10.6 / Ikea (Sweden) 26.8 (Retail) | Other big gainers on Bloomberg’s 6 Charles Koch 45.2 !4.3 / Koch Industries list include Hong Kong’s Galaxy (US) 10.5 (Diversified) Entertainment Group founder Lui 7 David Koch 45.2 !4.3 / Koch Industries BILLIONAIRE