This Land Is Our Land: the Multiple Claims of Devils Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stability of Leaning Column at Devils Tower National Monument, Wyoming

Stability of Leaning Column at Devils Tower National Monument, Wyoming By Edwin L. Harp and Charles R. Lindsay U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Harp, Edwin L., and Lindsay, Charles R., 2006, Stability of Leaning Column at Devils Tower National Monument, Wyoming: U.S. Geological Survey Open-file Report 2006–1130, 10 p. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Cover photograph: Devils Tower with leaning column visible (red arrow) at lower left edge of vertical shadow on tower face. ii Contents Abstract .....................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................................................1 -

Rocky Mountain Region

• Some major park roads are not plowed during winter. -oz • Hunting allowed only in National Recreation Areas and O » then is regulated; firearms must be broken down in other areas. 0°! • Every park has at least one visitor center and a variety of ro -n interpretive activities; be sure to take advantage of them! NATIONAL PARK AREAS IN THE • Keep peak-season travel plans flexible, since camp sl grounds, tours, or popular backcountry areas may be full when CO XT you arrive. • Special safety precautions are necessary in parks because S£ C<D C2D of dangers like wild animals, steep cliffs, or thermal areas — -"' -o stay alert and don't take chances. : rocky Once you're familiar with the variety and richness of National Most important, remember to have a good time! The parks are Park System areas, you'll no longer be satisfied with armchair 81 yours to preserve, use, and enjoy. 00° traveling. These natural, historic, and recreational sites com 0 > prise part of an astounding system that began in 1872, when a IV> DO Colorado 01 =;• group of forward-looking men saw the need to preserve unique en mountain features of our nation, without impairment, for the future. We ©BENT'S OLD FORT NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE O still enjoy the fruits of their idea, the first system of national 3; Here on the banks of the Arkansas River stands Bent's Old O parks in the world, and so—with your help—will generations to Fort — reconstructed and refurbished adobe fur-trading post, CD come. Indian rendezvous, way station, and military staging base on This sampler will help you choose those areas you'd most like the Santa Fe Trail. -

2019 National Park Service Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTACT INFORMATION page one ACKNOWLEDGMENTS page one CONSERVATION LEGACY OVERVIEW page two EXECUTIVE SUMMARY page three STATEMENT OF PURPOSE page three OVERVIEW OF PROGRAM SUCCESS page five DEMOGRAPHICS & ACCOMPLISHMENTS page six PARK LOCATIONS page six PROGRAM & PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS page seven PARTICIPANT AND PARTNER EXPERIENCE page twenty-two CONCLUSION page twenty-three APPENDIX A: PRESS AND MEDIA page twenty-four APPENDIX B: PROJECTS page twenty-four ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS APPENDIX C: FUNDING Conservation Legacy would like to thank the National Park Service page twenty-six staff, Cooperators and Partners who make our shared vision, mission and programming a continued success. We absolutely could not APPENDIX D: OTHER DOI PROGRAMS page twenty-six positively impact these individuals, communities, and treasured places without you! APPENDIX E: INTERN SURVEY RESULTS page twenty-seven NPS STAFF AND UNITS: NPS Washington Office NPS Youth Programs NPS Rivers and Trails Conservation Assistance Program NPS Historic Preservation Training Center CONSERVATION LEGACY Region 1 North Atlantic Appalachian NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Region 2 South Atlantic Gulf FY2019 REPORT Region 3 Great Lakes Report Term: October 2018–September 2019 Region 4 Mississippi Basin Region 5 Missouri Basin CONTACT INFO Region 6 Arkansas Rio Grande Texas Gulf FOR CONSERVATION LEGACY: Region 7 Upper Colorado Basin Amy Sovocool, Chief External Affairs Officer Region 8 Lower Colorado Basin 701 Camino del Rio, Suite 101 Region 9 Colombia Pacific Northwest Durango, Colorado 81301 Region 10 California Great Basin Email: [email protected] Region 11 Alaska Phone: 970-749-1151 Region 12 Pacific Islands www.conservationlegacy.org 1 OVERVIEW FOSTERING CONSERVATION SERVICE IN SUPPORT OF COMMUNITIES & ECOSYSTEMS LOCAL ACTION. -

NPS Intermountain Region Parks

Appendix A – List of parks available for collection Table 1 – NPS Intermountain Region Parks PARK PAVED ROAD PARK NAME STATE ALPHA MILES TO COLLECT ALFL Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument 2.287 TX AMIS Amistad National Recreation Area 6.216 TX ARCH Arches National Park 26.024 UT AZRU Aztec Ruins National Monument 0.068 NM BAND Bandelier National Monument 5.887 NM BEOL Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site 0.142 CO BIBE Big Bend National Park 122.382 TX BICA Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area 41.001 MT, WY BLCA Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park 8.947 CO BRCA Bryce Canyon National Park 28.366 CO CACH Canyon de Chelly National Monument 24.318 NM CAGR Casa Grande Ruins National Monument 0.848 AZ CANY Canyonlands National Park 52.55 UT CARE Capitol Reef National Park 9.056 UT CAVE Carlsbad Caverns National Park 7.898 NM CAVO Capulin Volcano National Monument 2.677 NM CEBR Cedar Breaks National Monument 7.266 UT CHAM Chamizal National Memorial 0.526 TX CHIC Chickasaw National Recreation Area 20.707 OK CHIR Chiricahua National Monument 9.107 AZ COLM Colorado National Monument 25.746 CO CORO Coronado National Memorial 3.631 AZ CURE Curecanti National Recreation Area 5.91 CO DETO Devils Tower National Monument 4.123 WY DINO Dinosaur National Monument 60.643 CO, UT ELMA El Malpais National Monument 0.26 NM ELMO El Morro National Monument 1.659 NM FOBO Fort Bowie National Historic Site 0.481 AZ FOBU Fossil Butte National Monument 3.633 WY FODA Fort Davis National Historic Site 0.361 TX FOLA Fort Laramie National Historic Site 1.027 WY FOUN Fort Union National Monument 0.815 NM GICL Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument 0.881 NM GLAC Glacier National Park 116.266 MT GLCA Glen Canyon National Recreation Area 58.569 UT, AZ GRCA Grand Canyon National Park 108.319 AZ GRSA Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve 7.163 CO PARK PAVED ROAD PARK NAME STATE ALPHA MILES TO COLLECT GRTE Grand Teton National Park 142.679 WY GUMO Guadalupe Mountains National Park 7.113 TX HOAL Horace M. -

Agate Fossil Beds

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 1980 Agate Fossil Beds Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark "Agate Fossil Beds" (1980). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 160. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/160 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Agate Fossil Beds cap. tfs*Af Clemson Universit A *?* jfcti *JpRPP* - - - . Agate Fossil Beds Agate Fossil Beds National Monument Nebraska Produced by the Division of Publications National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1980 — — The National Park Handbook Series National Park Handbooks, compact introductions to the great natural and historic places adminis- tered by the National Park Service, are designed to promote understanding and enjoyment of the parks. Each is intended to be informative reading and a useful guide before, during, and after a park visit. More than 100 titles are in print. This is Handbook 107. You may purchase the handbooks through the mail by writing to Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC 20402. About This Book What was life like in North America 21 million years ago? Agate Fossil Beds provides a glimpse of that time, long before the arrival of man, when now-extinct creatures roamed the land which we know today as Nebraska. -

54 Part 7—Special Regulations, Areas Of

Pt. 7 36 CFR Ch. I (7–1–07 Edition) PART 7—SPECIAL REGULATIONS, 7.53 Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument. AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK 7.54 Theodore Roosevelt National Park. SYSTEM 7.55 Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area. Sec. 7.56 Acadia National Park. 7.1 Colonial National Historical Park. 7.57 Lake Meredith National Recreation 7.2 Crater Lake National Park. Area. 7.3 Glacier National Park. 7.58 Cape Hatteras National Seashore. 7.4 Grand Canyon National Park. 7.59 Grand Portage National Monument. 7.5 Mount Rainier National Park. 7.60 Herbert Hoover National Historic Site. 7.6 Muir Woods National Monument. 7.61 Fort Caroline National Memorial. 7.7 Rocky Mountain National Park. 7.62 Lake Chelan National Recreation Area. 7.8 Sequoia and Kings Canyon National 7.63 Dinosaur National Monument. Parks. 7.64 Petersburg National Battlefield. 7.9 St. Croix National Scenic Rivers. 7.65 Assateague Island National Seashore. 7.10 Zion National Park. 7.66 North Cascades National Park. 7.11 Saguaro National Park. 7.67 Cape Cod National Seashore. 7.12 Gulf Islands National Seashore. 7.68 Russell Cave National Monument. 7.13 Yellowstone National Park. 7.69 Ross Lake National Recreation Area. 7.14 Great Smoky Mountains National 7.70 Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Park. 7.71 Delaware Water Gap National Recre- 7.15 Shenandoah National Park. ation Area. 7.16 Yosemite National Park. 7.72 Arkansas Post National Memorial. 7.17 Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation 7.73 Buck Island Reef National Monument. Area. 7.74 Virgin Islands National Park. -

National Parks, Monuments, and Historical Landmarks Visited

National Parks, Monuments, and Historical Landmarks Visited Abraham Lincoln Birthplace, KY Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, AZ Acadia National Park, ME Castillo de San Marcos, FL Adirondack Park Historical Landmark, NY Castle Clinton National Monument, NY Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument, TX Cedar Breaks National Monument, UT Agua Fria National Monument, AZ Central Park Historical Landmark, NY American Stock Exchange Historical Landmark, NY Chattahoochie River Recreation Area, GA Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, CA Chattanooga National Military Park, TN Angel Mounds Historical Landmark, IN Chichamauga National Military Park, TN Appalachian National Scenic Trail, NJ & NY Chimney Rock National Monument, CO Arkansan Post Memorial, AR Chiricahua National Monument, CO Arches National Park, UT Chrysler Building Historical Landmark, NY Assateague Island National Seashore, Berlin, MD Cole’s Hill Historical Landmark, MA Aztec Ruins National Monument, AZ Colorado National Monument, CO Badlands National Park, SD Congaree National Park, SC Bandelier National Monument, NM Constitution Historical Landmark, MA Banff National Park, AB, Canada Crater Lake National Park, OR Big Bend National Park, TX Craters of the Moon National Monument, ID Biscayne National Park, FL Cuyahoga Valley National Park, OH Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, CO Death Valley National Park, CA & NV Blue Ridge, PW Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, NJ & PA Bonneville Salt Flats, UT Denali (Mount McKinley) National Park. AK Boston Naval Shipyard Historical -

The Places Nobody Knows

THE OWNER’S GUIDE SERIES VOLUME 3 nobodthe places y knows Presented by the National Park Foundation www.nationalparks.org About the Author: Kelly Smith Trimble lives, hikes, gardens, and writes in North Cascades National Park Knoxville, Tennessee. She earned a B.A. in English from Sewanee: The University of the South and an M.S. in Environmental Studies from Green Mountain College. When not writing about gardening and the outdoors, Kelly can be found growing vegetables, volunteering for conservation organizations, hiking and canoeing the Southeast, and traveling to national parks. Copyright 2013 National Park Foundation. 1110 Vermont Ave NW, Suite 200, Washington DC 20005 www.nationalparks.org NATIONALPARKS.ORG | 2 Everybody loves Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon, and with good reason. Those and other icons of the National Park System are undeniably spectacular, and to experience their wonders is well worth braving the crowds they inevitably draw. But lest you think the big names are the whole story, consider that the vast park network also boasts plenty of less well-known destinations that are beautiful, historic, or culturally significant—or all of the above. Some of these gems are off the beaten track, others are slowly rising to prominence, and a few are simply overshadowed by bigger, better-publicized parks. But these national parks, monuments, historic places, and recreation areas are overlooked by many, and that’s a mistake you won’t want to make. nobodthe places y knows For every Yosemite, there’s a lesser-known park where the scenery shines and surprises. NATIONALPARKS.ORG | 3 1 VISIT: Bandelier National Monument VISIT: Big South Fork National River and IF YOU LOVE: Mesa Verde National Park Recreation Area FOR: Archaeologist’sthe dream placesIF YOU LOVE: Olympic National Park FOR: A range of outdoor recreation Few and precious places give us great insight Any traveler to Olympic National Park can 1| into the civilizations that lived on this land long 2| confirm that variety truly is the spice of life, before it was called the United States. -

Name Bear Lodge Was "Well Applied" and Should Be Retained (1880:221) Early Exceptions Who Accepted Dodge1s New Name Were a Military Engineer, Major G

NAMING BEAR LODGE D. White, 1998, Page 3 BACKGROUND Theodore Roosevelt created Devils Tower National Monument in 1906, as the first national monument in the United States. The name of the monument came from its central feature, a tower-like column ofphonolite porphyry 8651 high, which first appeared on published maps in 11 11 I857 as "Bears Lodge ( a direct and correct translation ofthe Lakota name "Mato Tipi ) but was renamed by Col. Richard Irving Dodge in 1875 as "Devil's Tower, 11 an epithet which Dodge claimed to be a "proper modification" of the "Indian" name "Bad God's Tower." The new name was at first scorned even by the scientific members of Dodge's expedition, and variants of "Bear Lodge" and "Mato Tipi" (the original Lakota name) continued to appear on published maps. In later years Maj. Gen. H. L. Scott attempted to have the name "Devil's Tower" removed from the feature. However, largely due to the success of Dodge1s several books (Sundance Times 1927, Kiger 1996d), and perhaps partly due to sentiments toward Indian people, the name "Devil's Tower" became most widely used. A diverse set of indigenous names continued to be used by American Indian Tribes having historical and cultural affiliation with the tower. With increasing institutional attention to American Indian cultural issues emerging in the final quarter of the twentieth century, the matter of the name emerged once again into public debate. When the National Park Service commissioned an ethnographic overview ofDevils Tower National Monument, the name was identified as a key issue and the researchers recommended that the National Park Service "consider renaming Devils Tower, giving it a name (proposed by the tribes) that is more ethnographically appropriate" (Hanson and Chirinos 1997:34). -

The Use and Potential Misuse of 3D and Spatial Heritage Data in Our Nation’S Parks

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications Tampa Library 12-2019 The Use and Potential Misuse of 3D and Spatial Heritage Data in Our Nation’s Parks Lori D. Collins University of South Florida, [email protected] Travis Doering University of South Florida, [email protected] Jorge Gonzalez University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/dhhc_facpub Scholar Commons Citation Collins, Lori D.; Doering, Travis; and Gonzalez, Jorge, "The Use and Potential Misuse of 3D and Spatial Heritage Data in Our Nation’s Parks" (2019). Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications. 21. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/dhhc_facpub/21 This Technical Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Tampa Library at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 | P a g e The Use and Potential Misuse of 3D and Spatial Heritage Data in Our Nation’s Parks Lori D. Collins, Ph.D., Travis Doering, Ph.D. and Jorge Gonzalez Digital Heritage and Humanities Collections, University of South Florida Libraries The Use and Potential Misuse of 3D and Spatial Heritage Data in Our Nation’s Parks i | P a g e Abstract Imaging and laser scanning technologies, associated advancements in methods for using the data collected with these instruments, and the rise and availability of mobile platforms such as UAVs for deploying these technologies, are greatly assisting professional archeologists in locating, documenting, managing, and preserving archeological and heritage sites. -

Geology of Devils Tower National Monument Wyoming

Geology of /« H t» , Devils Tower tl National Monument Wyoming GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1021-1 O S3 oSc o os *3 w T A CONTRIBUTION TO GENERAL GEOLOGY By CHARLES S. ROBINSON ABSTRACT Devils Tower is a steep-sided mass of igneous rock that rises above tne sur- ^ ronnding hills and the valley of the Belle Fourche River in Crook County, Wyo. It is composed of a crystalline rock, classified as phonolite porphyry, that when -(. fresh is gray but which weathers to green or brown. Vertical joints divide the rock mass into polygonal columns that extend from just above the base to the * top of the Tower. i The hills in the vicinity and at the base of the Tower are composed of red, 1 yellow, green, or gray sedimentary rocks that consist of sandstone, shale, or gypsum. These rocks, in aggregate about 400 feet thick, include, from oldest to youngest, the upper part of the Spearfish formation, of Triassic age, the A Gypsum Spring formation, of Middle Jurassic age, and the Sundance formation, of Late Jurassic age. The Sundance formation consists of the Stockade Beaver ~t, shale member, the Hulett sandstone member, the Lak member, and the Red- water shale member. * The formations have been only slightly deformed by faulting and folding. Within 2,000 to 3,000 feet of the Tower, the strata for the most part dip at 3°-5° towards the Tower. Beyond this distance, they dip at 2°-5° from the Tower. The Tower is believed to have been formed by the intrusion of magma into the sedimentary rocks, and the shape of the igneous mass formed by the cooled k . -

Devils Tower

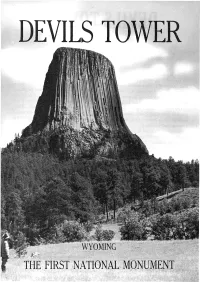

DEVILS TOWER WYOMING THE FIRST NATIONAL MONUMENT The "town" is generally inactive during visit before you walk along the Tower Trail. the heat of the day in warm weather. In Ranger-naturalists conduct campfire pro DEVILS TOWER winter, the prairie dogs will come out of grams at night during the summer. their burrows to bask in the sun during the warmest time of the day. They stay under The Toiver Trail NATIONAL MONUMENT ground when the weather is wet, or when it This trail is gently graded as it encircles is cold. A roadside exhibit tells you some the tower. Along it you will find a wealth thing of their way of life. of natural history information in the plants, An 865-foot monolith, evidence of geologic activity millions of years ago animals, and rocks. ABOUT YOUR VISIT Indian relics have been found at a point just off of the Tower Trail. This site This National Monument was established From the east entrance of the monument 3 Geology (marked by a sign) was an Indian workplace on September 24, 1906, by President Theo miles of oil-surfaced road leads to the visitor and lookout point. You will want to stop dore Roosevelt's proclamation under the Geologists agree that the rock of Devils center and the Tower Trail parking area. here for the superb view up the Belle Fourche authority of the Antiquities Act and became Tower was at one time molten or plastic. Valley. the first of many National Monuments to be About 50 million years ago this material was Interpretive Services set aside for the people of the United States.