George Collier Master Baker of Branscombe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Chapel Row, Branscombe, Seaton, Devon, EX12 3AZ

1 Chapel Row, Branscombe, Seaton, Devon, EX12 3AZ An outstanding Grade II Listed end of terrace cottage currently let as a successful holiday cottage. Sidmouth 5 miles Honiton 8.6 miles • Three Bedrooms • Sitting Room With Inglenook • Kitchen/ Dining room • Bathroom and downstairs shower room • Private Gardens • Established holiday let • Character Offers in excess of £325,000 01404 45885 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London stags.co.uk 1 Chapel Row, Branscombe, Seaton, Devon, EX12 3AZ SITUATION OUTSIDE A charming thatched cottage set the highly regarded The garden predominately laid to lawn with mature coastal village of Branscombe with its well-regarded hedging and a stone path. The parking area across the village school, two popular public houses and stunning road has parking for around 2 cars. beach. This delightful part of East Devon which has been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty forms SERVICES a major part of the Jurassic coast, a World Heritage site, Mains water, electricity and drainage. renowned for its dramatic cliffs and golden beaches. DIRECTIONS From the A3052 at Branscombe Cross travel south, sign There is a range of good independent schools in the area posted to Branscombe and Bulstone, continue on this with the revered Colyton Grammar School within easy road, passing the Fountain Head pub, for 1.7 miles and reach. The nearby Sidmouth provides for most everyday the property is on the left. requirements, including schools, shops, banks, post office, library, theatre and cinema. Honiton lies inland and offers a main line rail service to London Waterloo. Exeter is approximately 21 miles to the west with further amenities, a main line rail link to London Paddington, the M5 motorway and an International airport. -

Final Report

Parishscapes Project PNNU –PNON YF>C<>C< H=: E6GH HD A>;: Evaluation Report J<KDLCL><J@L C<L =@@H LNJJIKM@? =P Contents a6>C F:EDFH Glossary of Abbreviations Used in This Report R O Project Background S P Project Aims and Achievements T Q Structure and Delivery V R Overview of Outputs OP S Quantative Evaluation PO T Qualitative Evaluation PR U Conclusions and Acknowledgements QW Appendices: X School Tithe Map Workshop – St Peter’s Primary School RP Y Emails and Feedback from a Range of Contacts RS Z Apportionment Guidelines SS [ Finances SU \L86J6H>DC D; 6 9:G:FH:9 8DHH6<: 6H fIBB:F9DKC ]6FB, bDFH=A:><=, [:JDC List of Figures and Image Acknowledgements TN O Abstract TO P Introduction TP Q The Survey and the Site Before Excavation TR R The Geophysical Survey by Richard Sandover TU S The Excavation UN T The Pottery UV U The Metalwork VP V Building Materials, Glass and Faunal Remains VS W Worked Stone and Flint VU ON The Documentary Evidence by Ron Woodcock and Philippe Planel WN OO Lees Cottage and the Surrounding Landscape WT OP Acknowledgements and References WV Parishscapes Project PNNU –PNON YF>C<>C< H=: E6GH HD A>;: Main Report ^ADGG6FM D; 677F:J>6H>DCG BFILL<KP IA <==K@OD<MDIHL NL@? DH MCDL K@JIKM "! Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Apportionment The supporting recording sheets for the tithe maps Devon County Council #" Devon Record Office East Devon District Council Geo-rectification Modifying boundaries of old maps to fit modern day electronic maps $ Geographical Information System – digitally mapped information #/$ Historic Environment Record/Service – record based in ?>> % Information Technology – the service/use of computers and electronic equipment for information Polygonisation Assigning information to individual parcels (e.g. -

899S Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

899S bus time schedule & line map 899S Seaton - Sidford - Sidmouth - Budleigh Salterton View In Website Mode - Littleham The 899S bus line (Seaton - Sidford - Sidmouth - Budleigh Salterton - Littleham) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Budleigh Salterton: 6:45 AM (2) Littleham: 3:50 PM (3) Newton Poppleford: 7:20 AM - 3:50 PM (4) Seaton: 7:45 AM - 4:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 899S bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 899S bus arriving. Direction: Budleigh Salterton 899S bus Time Schedule 17 stops Budleigh Salterton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:45 AM Marine Place, Seaton Marine Place, Seaton Tuesday 6:45 AM Newlands Park, Seaton Wednesday Not Operational Hangman's Stone, Branscombe Thursday Not Operational Friday Not Operational Three Horseshoes Inn, Street Saturday Not Operational King's Down Tail, Trow Donkey Sanctuary, Trow Packhorse Close, Sidford 899S bus Info Trow Hill, Sidmouth Direction: Budleigh Salterton Stops: 17 Trow Farm, Trow Trip Duration: 39 min A3052, Sidmouth Civil Parish Line Summary: Marine Place, Seaton, Newlands Park, Seaton, Hangman's Stone, Branscombe, Three Packhorse Close, Sidford Horseshoes Inn, Street, King's Down Tail, Trow, Trow Hill, Sidmouth Donkey Sanctuary, Trow, Packhorse Close, Sidford, Trow Farm, Trow, Packhorse Close, Sidford, Spar, Spar, Sidford Sidford, Burscombe Lane, Sidford, Core Hill Road, Sidmouth, The Bowd, Bowd, Lower Way, Newton Burscombe Lane, Sidford Poppleford, Millmoor Lane, Newton Poppleford, -

L L L L 0826 L L 0941 L 41 L L from 26Th May 2019

Exmouth . Budleigh Salterton . Otterton . Newton Poppleford . Sidmouth 157 Exmouth Community College . Budleigh Salterton 257 Exmouth . Cranford Avenue . Budleigh Salterton 357 MONDAYS to FRIDAYS except Bank Holidays Service No. 157 157 157 157 357 357 157 357 157 357 157 357 157 257 357 157 357 157 Byron Way Lovering Close 0823 Exmouth Parade 0628 0635 0705 0740 0815 0835 0900 0930 00 30 1400 1430 1500 1535 1605 1630 1705 Exmouth Rolle Street 0630 0637 0707 0742 0820 0836 0905 0935 05 35 1405 1435 1505 1540 1610 1635 1710 Cranford Avenue Merrion Avenue 0826 0941 41 1441 1546 1641 Exmouth Community College l l l l l l then l l l 1510 l l Littleham Tesco 0637 0644 0715 0750 0831 0842 0913 0946 at 13 46 1413 1446 1513 1523 1551 1618 1646 1718 Budleigh Salterton Public Hall 0645 0652 0725 0800 0842 0850 0923 0957 these 23 57 until 1423 1457 1523 1533 1602 1628 1657 1728 Budleigh Salterton Granary Lane 0655 0728 0803 0855 0926 times 26 1426 1526 1536 1631 1731 East Budleigh High Street 0659 0732 0807 0930 each 30 1430 1530 1635 1735 Otterton Village 0703 0812 l 0935 hour 35 1435 1535 1640 1740 Bicton Park Entrance 0706 0816 l 0939 39 1439 1539 1644 1744 Bicton College 0905 Colaton Raleigh 0709 0819 0942 42 1442 1542 1647 1747 Newton Poppleford Memorial 0714 0824 0947 47 1447 1547 1652 1752 Sidmouth Alexandria Road 0831 0954 54 1454 1554 1659 1759 Sidmouth Triangle/3 Cornered Plot 0729 0840 1003 03 1503 1603 1708 1808 Service No. -

Transport Information

TIVERTON www.bicton.ac.uk 1hr 30mins CULLOMPTON TRANSPORT TRANSPORT GUIDELINES 55mins - The cost for use of the daily transport for all non-residential students can be paid for per HONITON INFORMATION term or in one payment in the Autumn term to cover the whole year - Autumn, Spring & CREDITON 45mins Summer terms. 1hr 5mins AXMINSTER 1hr 10mins - No knives to be taken onto the contract buses or the college campus. - Bus passes will be issued on payment and must be available at all times for inspection. BICTON COLLEGE - Buses try to keep to the published times, please be patient if the bus is late it may have EXETER been held up by roadworks or a breakdown, etc. If you miss the bus you must make 30 - 45mins your own way to college or home. We will not be able to return for those left behind. - SEAT BELTS MUST BE WORN. DAWLISH LYME REGIS - All buses arrive at Bicton College campus by 9.00am. 1hr 25mins 1hr 20mins - Please ensure that you apply to Bicton College for transport. SIDMOUTH 15mins - PLEASE BE AT YOUR BUS STOP 10 MINUTES BEFORE YOUR DEPARTURE TIME. NEWTON ABBOT - Buses leave the campus at 5.00pm. 1hr SEATON 1hr - Unfortunately transport cannot be offered if attending extra curricular activities e.g. staying TEIGNMOUTH late for computer use, discos, late return from sports fixtures, equine duties or work 1hr 15mins experience placements. - Residential students can access the transport to go home at weekends by prior arrangement with the Transport Office. - Bicton College operates a no smoking policy in all of our vehicles. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Sea Cottage 42A FORE STREET, BUDLEIGH SALTERTON, DEVON, EX9 6NJ Sea Cottage 42A FORE STREET, BUDLEIGH SALTERTON, DEVON, EX9 6NJ

Sea Cottage 42A FORE STREET, BUDLEIGH SALTERTON, DEVON, EX9 6NJ Sea Cottage 42A FORE STREET, BUDLEIGH SALTERTON, DEVON, EX9 6NJ Exeter about 11 miles Exeter international airport about 11.2 miles Sidmouth about 6.5 miles A unique Grade II listed Georgian townhouse occupying a beautiful west facing sea front position overlooking Lyme Bay, one of East Devon’s finest Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Accommodation summary Sociable kitchen/dining room • Sitting room • WC Three bedrooms • Bathroom Courtyard garden SITUATION Sea Cottage is situated in a breath-taking location, tucked away within the sought after coastal town of Budleigh Salterton. Designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the town sits at the western end of the Jurassic Coastline, a World Heritage Site with a two mile stretch of pebble beach. The town has a good range of shops, cafes, restaurants, inns and a Post Office. It also has a thriving community and caters for a wide range of leisure activities, including tennis, bowls, croquet, badminton, cricket and golf course within easy reach. There are cycle paths and many lovely walks in the area, with the South West Coastal Footpath running along the coast line, as well as plenty of picnic spots and bird watching opportunities on the estuary of the River Otter. Budleigh Salterton also hosts a number of annual arts, music and literary events throughout the year. Communication links in the area are excellent, with good access to the M5 motorway (J31) and A30 at Exeter, together with mainline train stations, providing regular links to London Paddington and Waterloo. -

Various Roads, East Devon District) (Control of Waiting & Loading) Amendment Number 2 Order 2017

Devon County Council (Various Roads, East Devon District) (Control of Waiting & Loading) Amendment Number 2 Order 2017 Devon County Council make the following order under sections 1, 2, 4, 32, 35 & part IV of schedule 9 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 & of all other enabling powers 1 This order comes into force 25th September 2017 and may be cited as “Devon County Council (Various Roads, East Devon District) (Control of Waiting & Loading) Amendment Number 2 Order 2017” 2 The schedules in part 1 are added to Devon County Council (Traffic Regulation & On-Street Parking Places) Consolidation Order 2017 as amended and the lengths of road in part 2 are revoked from the corresponding schedules that order TOWNS INCLUDED Axminster Beer Budleigh Salterton Colyton Honiton Lympstone Ottery St Mary Seaton Sidmouth Stoke Canon PART 1 RESTRICTIONS AXMINSTER Schedule 1.001 No Waiting At Any Time Alexandra Road, Axminster (i) the east side from its junction with King Edward Road for a distance of 6 metres in a northerly direction (ii) the north-west side from its junction with King Edward Road to a point 34 metres south-west of its junction with Widepost Lane (iii) the south-east side from its junction with Widepost Lane for a distance of 42 metres in a south-westerly direction BEER Schedule 1.001 No Waiting At Any Time Causeway, Beer (i) the south side from its junction with Mare Lane for a distance of 49 metres in a south-easterly direction (ii) the south side from a point 97 metres east of its junction with Mare Lane for a distance of 97 metres -

Site Improvement Plan Sidmouth to West Bay

Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 Sites (IPENS) Planning for the Future Site Improvement Plan Sidmouth to West Bay Site Improvement Plans (SIPs) have been developed for each Natura 2000 site in England as part of the Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 sites (IPENS). Natura 2000 sites is the combined term for sites designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protected Areas (SPA). This work has been financially supported by LIFE, a financial instrument of the European Community. The plan provides a high level overview of the issues (both current and predicted) affecting the condition of the Natura 2000 features on the site(s) and outlines the priority measures required to improve the condition of the features. It does not cover issues where remedial actions are already in place or ongoing management activities which are required for maintenance. The SIP consists of three parts: a Summary table, which sets out the priority Issues and Measures; a detailed Actions table, which sets out who needs to do what, when and how much it is estimated to cost; and a set of tables containing contextual information and links. Once this current programme ends, it is anticipated that Natural England and others, working with landowners and managers, will all play a role in delivering the priority measures to improve the condition of the features on these sites. The SIPs are based on Natural England's current evidence and knowledge. The SIPs are not legal documents, they are live documents that will be updated to reflect changes in our evidence/knowledge and as actions get underway. -

Summer 2014 Free

SUMMER 2014 FREE Robots raise money for a Water Survival Box Page 26 Sea Creatures at Charmouth Primary School Page 22 Winter Storms Page 30 Superfast Mary Anning Broadband – Realities is Here! Page 32 Page 6 Five Gold Stars Page 19 Lost Almshouses Page 14 Sweet flavours of Margaret Ledbrooke and her early summer future daughter-in-law Page 16 Natcha Sukjoy in Auckland, NZ SHORELINE SUMMER 2014 / ISSUE 25 1 Shoreline Summer 2014 Award-Winning Hotel and Restaurant Four Luxury Suites, family friendly www.whitehousehotel.com 01297 560411 @charmouthhotel Contemporary Art Gallery Morcombelake Fun, funky and Dorset DT6 6DY 01297 489746 gorgeous gifts Open Tuesday to Saturday 10am – 5pm for everyone! Next to Charmouth Stores (Nisa) www.artwavewest.com The Street, Charmouth - Tel 01297 560304 CHARMOUTH STORES Your Local Store for more than 198 years! Open until 9pm every night The Street, Charmouth. Tel 01297 560304 2 SHORELINE SUMMER 2014 / ISSUE 25 Editorial Charmouth Traders Summer 2014 Looking behind, I am filled n spite of the difficult economic conditions over the last three or four years it with gratitude. always amazes me that we have the level of local shops and services that we Ido in Charmouth. There are not many (indeed I doubt if there are any) villages Looking forward, I am filled nowadays that can boast two pubs, a pharmacy, a butcher, a flower shop, two with vision. hairdressers, a newsagents come general store like Morgans, two cafes, fish and chip shops, a chocolate shop, a camping shop, a post office, the Nisa store Looking upwards, I am filled with attached gift shop, as well as a variety of caravan parks, hotels, B&Bs and with strength. -

Strategic Planning Committee Date of Meeting: 10Th June 2019 Public Document: Yes Exemption: None

Report to: Strategic Planning Committee Date of Meeting: 10th June 2019 Public Document: Yes Exemption: None Review date for None release Agenda 7 Subject: Review of East Devon Area of Special Control of Advertisements (ASCA) Purpose of report: To seek Members agreement to recommend that full Council make changes to the areas included in the East Devon Area of Special Control of Advertisements. Recommendation: 1. That this Committee recommend that full Council make amendments to the areas covered by the Area of Special Control of Advertisements as set out in the attached draft schedule (Appendix 2). 2. That the Service Lead – Planning Strategy and Development Management be authorised to make minor changes to the draft modification Order (Appendix 2) prior to finalisation. This is intended to cover the production of more detailed plans to indicate the changes proposed and any minor wording updates that may be necessary. Reason for To ensure that the appropriate areas are covered by the Area of Special recommendation: Control of Advertisements. Officer: Linda Renshaw, Senior Planning Policy Officer Email [email protected] Tel: 01395 571 683 Financial There are no direct financial implication resulting from the implications: recommendations Legal implications: This modified order designating amended areas of special control is made under the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and will only come into effect once approved by the Secretary of State. This approval is a formal process where objections are invited and may be made following receipt a hearing may be required with consideration of the representations before approval is issued. Other than this there are no other legal implications Equalities impact: Low Impact Changes to the Area of Special Control of Advertisements will not have specific equalities impacts Risk: Low Risk The Area of Special Control of Advertisements has been reviewed and consulted on in accordance with legal requirements. -

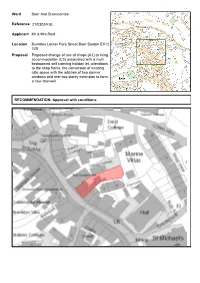

Ward Beer and Branscombe Reference 21/0302/FUL Applicant

Ward Beer And Branscombe Reference 21/0302/FUL Applicant Mr & Mrs Reid Location Bumbles Locker Fore Street Beer Seaton EX12 3JB Proposal Proposed change of use of shops (A1) to living accommodation (C3) associated with a multi bedroomed self catering holiday let, alterations to the shop fronts, the conversion of existing attic space with the addition of two dormer windows and rear two storey extension to form a new stairwell RECOMMENDATION: Approval with conditions Crown Copyright and database rights 2021 Ordnance Survey 100023746 Committee Date: 5th May 2021 Beer And Target Date: Branscombe 21/0302/FUL 01.04.2021 (Beer) Applicant: Mr & Mrs Reid Location: Bumbles Locker Fore Street Proposal: Proposed change of use of shops (A1) to living accommodation (C3) associated with a multi bedroomed self catering holiday let, alterations to the shop fronts, the conversion of existing attic space with the addition of two dormer windows and rear two storey extension to form a new stairwell RECOMMENDATION: Approval with conditions EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The application is presented to committee as the officer recommendation differs from that of the ward member. The proposal relates to a mixed use property located in the centre of Beer within the defined built-up area boundary and village centre and the designated Beer Conservation Area. The ground floor of the front part of the property has a lawful commercial use, most recently for retail purposes but currently vacant. It is subdivided into 2 no. units a larger unit to the left and smaller unit to the right. The remainder of the ground floor and the first floor of the building are in residential use as a single unit.