Property in Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Intellectual Property Law

ee--RRGG Electronic Resource Guide International Intellectual Property Law * Jonathan Franklin This page was last updated February 8, 2013. his electronic resource guide, often called the ERG, has been published online by the American Society of International Law (ASIL) since 1997. T Since then it has been systematically updated and continuously expanded. The chapter format of the ERG is designed to be used by students, teachers, practitioners and researchers as a self-guided tour of relevant, quality, up-to-date online resources covering important areas of international law. The ERG also serves as a ready-made teaching tool at graduate and undergraduate levels. The narrative format of the ERG is complemented and augmented by EISIL (Electronic Information System for International Law), a free online database that organizes and provides links to, and useful information on, web resources from the full spectrum of international law. EISIL's subject-organized format and expert-provided content also enhances its potential as teaching tool. 2 This page was last updated February 8, 2013. I. Introduction II. Overview III. Research Guides and Bibliographies a. International Intellectual Property Law b. International Patent Law i. Public Health and IP ii. Agriculture, Plant Varieties, and IP c. International Copyright Law i. Art, Cultural Property, and IP d. International Trademark Law e. Trade and IP f. Arbitration, Mediation, and IP g. Traditional Knowledge and IP h. Geographical Indications IV. General Search Strategies V. Primary Sources VI. Primary National Legislation and Decisions VII. Recommended Link sites VIII. Selected Non-Governmental Organizations IX. Electronic Current Awareness 3 This page was last updated February 8, 2013. -

Tragedy of the Commons : Th

tragedy of the commons : The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_T000193&pr... tragedy of the commons Elinor Ostrom From The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Second Edition, 2008 Edited by Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume Abstract ‘The tragedy of the commons’ arises when it is difficult and costly to exclude potential users from common-pool resources that yield finite flows of benefits, as a result of which those resources will be exhausted by rational, utility-maximizing individuals rather than conserved for the benefit of all. Pessimism about the possibility of users voluntarily cooperating to prevent overuse has led to widespread central control of common-pool resources. But such control has itself frequently resulted in resource overuse. In practice, especially where they can communicate, users often develop rules that limit resource use and conserve resources. Keywords collective action; common-pool resources; common property; free rider problem; Hardin, G.; open-access resources; private property; social dilemmas; state property; tragedy of the commons Article The term ‘the tragedy of the commons’ was first introduced by Garrett Hardin (1968) in an important article in Science. Hardin asked us to envision a pasture ‘open to all’ in which each herder received large benefits from selling his or her own animals while facing only small costs of overgrazing. When the number of animals exceeds the capacity of the pasture, each herder is still motivated to add more animals since the herder receives all of the proceeds from the sale of animals and only a partial share of the cost of overgrazing. -

What Is So Special About Intangible Property? the Case for Intelligent Carryovers Richard A

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2010 What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The Case for intelligent Carryovers Richard A. Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Epstein, "What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The asC e for intelligent Carryovers" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 524, 2010). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 524 (2D SERIES) What Is So Special about Intangible Property? The Case for Intelligent Carryovers Richard A. Epstein THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO August 2010 This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. WHAT IS SO SPECIAL ABOUT INTANGIBLE PROPERTY? THE CASE FOR INTELLIGENT CARRYOVERS by Richard A. Epstein* ABSTRACT One of the major controversies in modern intellectual property law is the extent to which property rights conceptions, developed in connection with land or other forms of tangible property, can be carried over to different forms of property, such as rights in the spectrum or in patents and copyrights. -

Public Notices & the Courts

PUBLIC NOTICES B1 DAILY BUSINESS REVIEW TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021 dailybusinessreview.com & THE COURTS BROWARD PUBLIC NOTICES BUSINESS LEADS THE COURTS WEB SEARCH FORECLOSURE NOTICES: Notices of Action, NEW CASES FILED: US District Court, circuit court, EMERGENCY JUDGES: Listing of emergency judges Search our extensive database of public notices for Notices of Sale, Tax Deeds B5 family civil and probate cases B2 on duty at night and on weekends in civil, probate, FREE. Search for past, present and future notices in criminal, juvenile circuit and county courts. Also duty Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach. SALES: Auto, warehouse items and other BUSINESS TAX RECEIPTS (OCCUPATIONAL Magistrate and Federal Court Judges B14 properties for sale B8 LICENSES): Names, addresses, phone numbers Simply visit: CALENDARS: Suspensions in Miami-Dade, Broward, FICTITIOUS NAMES: Notices of intent and type of business of those who have received https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/public-notices/ and Palm Beach. Confirmation of judges’ daily motion to register business licenses B3 calendars in Miami-Dade B14 To search foreclosure sales by sale date visit: MARRIAGE LICENSES: Name, date of birth and city FAMILY MATTERS: Marriage dissolutions, adoptions, https://www.law.com/dailybusinessreview/foreclosures/ DIRECTORIES: Addresses, telephone numbers, and termination of parental rights B8 of those issued marriage licenses B3 names, and contact information for circuit and CREDIT INFORMATION: Liens filed against PROBATE NOTICES: Notices to Creditors, county -

Lifeboat Ethics: the Case Against Helping the Poor

Lifeboat Ethics: the Case Against Helping the Poor by Garrett Hardin, Psychology Today, September 1974 Environmentalists use the metaphor of the earth as a "spaceship" in trying to persuade countries, industries and people to stop wasting and polluting our natural resources. Since we all share life on this planet, they argue, no single person or institution has the right to destroy, waste, or use more than a fair share of its resources. But does everyone on earth have an equal right to an equal share of its resources? The spaceship metaphor can be dangerous when used by misguided idealists to justify suicidal policies for sharing our resources through uncontrolled immigration and foreign aid. In their enthusiastic but unrealistic generosity, they confuse the ethics of a spaceship with those of a lifeboat. A true spaceship would have to be under the control of a captain, since no ship could possibly survive if its course were determined by committee. Spaceship Earth certainly has no captain; the United Nations is merely a toothless tiger, with little power to enforce any policy upon its bickering members. If we divide the world crudely into rich nations and poor nations, two thirds of them are desperately poor, and only one third comparatively rich, with the United States the wealthiest of all. Metaphorically each rich nation can be seen as a lifeboat full of comparatively rich people. In the ocean outside each lifeboat swim the poor of the world, who would like to get in, or at least to share some of the wealth. What should the lifeboat passengers do? First, we must recognize the limited capacity of any lifeboat. -

An Ethical Defense of Global-Warming Skepticism —William Irwin and Brian Williams Adam Smith on Economic Happiness —Douglas J

REASON PAPERS A Journal of Interdisciplinary Normative Studies Articles An Ethical Defense of Global-Warming Skepticism —William Irwin and Brian Williams Adam Smith on Economic Happiness —Douglas J. Den Uyl and Douglas B. Rasmussen Direct and Overall Liberty: Areas and Extent of Disagreement —Daniel B. Klein and Michael J. Clark Violence and Postmodernism: A Conceptual Analysis —Iddo Landau Providing for Aesthetic Experience —Jason Holt Why Has Aesthetic Formalism Fallen on Hard Times? —David E. W. Fenner Austro-Libertarian Publishing: A Survey and Critique —Walter E. Block Discussion Notes Left-Libertarianism—An Oxymoron? —Tibor R. Machan Rejoinder to Hoppe on Indifference Once Again —Walter E. Block with William Barnett II Review Essay Review Essay: Edward Feser’s Locke and Eric Mack’s John Locke —Irfan Khawaja Book Review James Stacey Taylor’s Practical Autonomy and Bioethics —Thomas D. Harter Vol. 32 Fall 2010 Editor-in-Chief: Aeon J. Skoble Managing Editors: Carrie-Ann Biondi Irfan Khawaja Editor Emeritus: Tibor R. Machan Editorial Board: Jordon Barkalow Walter Block Peter Boettke Donald Boudreaux Nicholas Capaldi Andrew I. Cohen Douglas J. Den Uyl Randall Dipert John Hasnas Stephen Hicks John Hospers William T. Irwin Kelly Dean Jolley N. Stephan Kinsella Stephen Kershnar Israel M. Kirzner Shawn Klein Leonard Liggio Eric Mack Fred D. Miller, Jr. Jennifer Mogg James Otteson Douglas Rasmussen Ralph Raico Lynn Scarlett David Schmidtz James Stacey Taylor Edward Younkins Matthew Zwolinski Reason Papers Vol. 32 Editorial The editorial to volume 26 of Reason Papers began with this: Reason Papers was founded in 1974 by Professor Tibor R. Machan, who edited the first twenty-five volumes. -

Community Property V. the Elective Share, 72 La

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University: DigitalCommons @ LSU Law Center Louisiana Law Review Volume 72 | Number 1 The Future of Community Property: Is the Regime Still Viable in the 21st Century? A Symposium Fall 2011 Community Property v. The lecE tive Share Terry L. Turnipseed Repository Citation Terry L. Turnipseed, Community Property v. The Elective Share, 72 La. L. Rev. (2011) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol72/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Community Property v. The Elective Share Terry L. Turnipseed I. INTRODUCTION There is certainly no doubt that community property has its faults. But, as with any flawed thing, one must look at it in comparison with the alternatives: separate property and its companion, the elective share. This Article argues that the elective share is so flawed that it should be jettisoned in favor of community property.' The elective share can trace its ancestry to dower and curtesy, with the concept of dower dating to ancient times.2 In old England, a widowed woman was given a life estate in one-third of certain of her husband's real property-property in which the husband held an inheritable or devisable interest during the marriage.3 Once dower attached to a parcel of land at the inception of the marriage, the husband could not unilaterally terminate it by transferring the land.4 The right would spring to life upon the husband's death unless the wife had also consented to the transfer by signing the deed, even if title were held in only the husband's name.5 Copyright 2011, by TERRY L. -

Confronting Remote Ownership Problems with Ecological Law

CONFRONTING REMOTE OWNERSHIP PROBLEMS WITH ECOLOGICAL LAW Geoffrey Garver* ABSTRACT ThomasBerry’s powerfulappeal foramutually enhancing human- Earthrelationshipfaces many challengesdue to theecological crisis that is co-identifiedwith dominant growth-insistenteconomic,political, andlegal systemsacrossthe world. Thedomains of environmental history, ecological restoration, and eco-culturalrestoration, as well as studies by Elinor Ostrom and othersofsustainableuse of commonpool resources,provide insightsonthe necessary conditions foramutually enhancing human-Earth relationship. Atheme commontothesedomains is theneed forintimate knowledgeofand connectiontoplace that requiresalong-standing commitment of people to theecosystems that sustainthem.Remoteprivate ownership—oftenbylarge and politically powerful multinational corporations financed by investorsseeking thehighest possiblereturns and lacking knowledgeorinterestinthe places and people they harm—is deeplyengrained in theglobal economic system.The historical rootsof remote ownership and controlgoback to territorial extensification associated with thesharpriseofcolonialismand long-distancetradeinthe earlymodernera.Yet remote owners’and investors’ detachment from place poses an enormous challenge in thequest foramutually enhancing human-Earthrelationship. ThisEssaypresents an analysis of how contemporary environmental lawundergirds theremoteownershipproblem and of how limits-insistentecological lawcouldprovide solutions. ABSTRACT..................................................................................................425 -

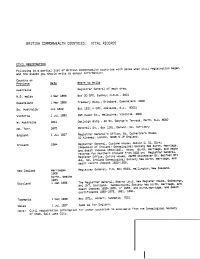

British Isles

BRITISH COMMONWEALTH COUNTRIES: VITAL RECORDS CIVIL REGISTRATICN Following is a partial list of British Ccmmcnwealth countries with dates when civil registration began, and the places you should writ~ to obtain information: Ccuntry or Prevince Q!!! Where to Write .Au$t'ralia Registrar Ganer-a! of each area. N.S. wales 1 Mar 1856 Sex 30 GPO, Sydney, N.S.W., 2001 Queensland 1 Mar 1856 Treasury Bldg., Brisbane, Queensland 4000 So. Australia Jul 1842 8ex 1531 H Gr\), Adelaide, S.A. 5CCCl Victoria 1 Jul 1853 295 Cuesn St., Melbourne, Victoria XCO W. .Australia 1841 Cak!eigh 61dg., 22 St. Gear-ge's Terrace, Perth, W.A. eoco Nc. Terr. 1870 Mitchell St., Box 1281. OarNin, Nc. Territory England 1 Jul 1837 Registrar General's Office, St. catherine's House, 10 Kinsway. Loncen, 'AC2S 6 JP England. Ireland 1864 Registrar General, Custcme House. Dublin C. 10, Eire, (Recuolic(Republic of Ireland) Genealogical Society has bir~h, marriage, and death indexes 1864-1921. Nete: Birth, rtarl"'iage,rmt'l"'iage, atld death records farfor Nor~hern Ireland frcm 1922 an: Registrar General, Regis~erOffice, Oxford House. 49~5 Chichester St. Selfast STI 4HL, No~ !re1.a.rld Genealcgical Scciety has birth, narriage, and death recordreccrd indexes 1922-l959~ New Z!!aland marriages Registrar General, P.O~ Sox =023, wellingtcn, New Zealand. 1008 birth, deaths 1924 Scotland 1 Jan 1855 The Registrar General, Search Unit, New Register House, Edinburgh, EHl 3YT, SCCtland~ Genealogical Saei~tyScei~ty has bir~h,birth, marriage, and death indexes 1855-1955, or 1956, and birt%'\ crarriage, and death cer~ificates 1855-1875, 1881. -

Strong Reciprocity and Human Sociality∗

Strong Reciprocity and Human Sociality∗ Herbert Gintis Department of Economics University of Massachusetts, Amherst Phone: 413-586-7756 Fax: 413-586-6014 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www-unix.oit.umass.edu/˜gintis Running Head: Strong Reciprocity and Human Sociality March 11, 2000 Abstract Human groups maintain a high level of sociality despite a low level of relatedness among group members. The behavioral basis of this sociality remains in doubt. This paper reviews the evidence for an empirically identifi- able form of prosocial behavior in humans, which we call ‘strong reciprocity,’ that may in part explain human sociality. A strong reciprocator is predisposed to cooperate with others and punish non-cooperators, even when this behavior cannot be justified in terms of extended kinship or reciprocal altruism. We present a simple model, stylized but plausible, of the evolutionary emergence of strong reciprocity. 1 Introduction Human groups maintain a high level of sociality despite a low level of relatedness among group members. Three types of explanation have been offered for this phe- nomenon: reciprocal altruism (Trivers 1971, Axelrod and Hamilton 1981), cultural group selection (Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman 1981, Boyd and Richerson 1985) and genetically-based altruism (Lumsden and Wilson 1981, Simon 1993, Wilson and Dugatkin 1997). These approaches are of course not incompatible. Reciprocal ∗ I would like to thank Lee Alan Dugatkin, Ernst Fehr, David Sloan Wilson, and the referees of this Journal for helpful comments, Samuel Bowles and Robert Boyd for many extended discussions of these issues, and the MacArthur Foundation for financial support. This paper is dedicated to the memory of W. -

Policy Makers Guide to Women's Land, Property and Housing Rights Across the World

POLICY MAKERS GUIDE TO WOMEN’S LAND, PROPERTY AND HOUSING RIGHTS ACROSS THE WORLD UN-HABITAT March 2007 POLICY MAKERS GUIDE TO WOMEN’S LAND, PROPERTY AND HOUSING RIGHTS ACROSS THE WORLD 1 Copyright (C) United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2006 All Rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) P.O. Box 30030, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 7621 234 Fax: +254 20 7624 266 Web: www.unhabitat.org Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the Governing Council of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, or its Member States. Acknowledgements: This guide is written by M. Siraj Sait, Legal Officer, Land, Tenure and Property Administration Section, Shelter Branch, UN-HABITAT and is edited by Clarissa Augustinus, Chief, Land, Tenure and Property Administration Section, Shelter Branch. A fuller list of credits appears as an appendix to this report. The research was made possible through support from the Governments of Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Norway. Further Information: Clarissa Augustinus, Chief Land, Tenure and Property Administration Section, Shelter Branch, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) P.O. Box 30030 Nairobi 00100, Kenya E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unhabitat.org 2 POLICY MAKERS GUIDE TO WOMEN’S LAND, PROPERTY AND HOUSING RIGHTS ACROSS THE WORLD TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery Siobhán McGrath Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science, New School University Economic Development & Global Governance and Independent Study: William Milberg Spring 2005 1. Introduction It is widely accepted that capitalism is characterized by “free” wage labor. But what is “free wage labor”? According to Marx a “free” laborer is “free in the double sense, that as a free man he can dispose of his labour power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale” – thus obliging the laborer to sell this labor power to an employer, who possesses the means of production. Yet, instances of “unfree labor” – where the worker cannot even “dispose of his labor power as his own commodity1” – abound under capitalism. The question posed by this paper is why. What factors can account for the existence of unfree labor? What role does it play in an economy? Why does it exist in certain forms? In terms of the broadest answers to the question of why unfree labor exists under capitalism, there appear to be various potential hypotheses. ¾ Unfree labor may be theorized as a “pre-capitalist” form of labor that has lingered on, a “vestige” of a formerly dominant mode of production. Similarly, it may be viewed as a “non-capitalist” form of labor that can come into existence under capitalism, but can never become the central form of labor. ¾ An alternate explanation of the relationship between unfree labor and capitalism is that it is part of a process of primary accumulation.