Intellectual Property Law Section of the State Bar of Texas the University of Texas School of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

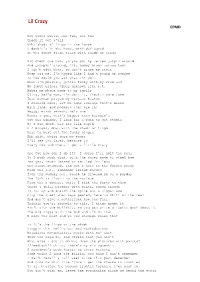

EPMD Lil Crazy

Lil Crazy EPMD Hey young world, one two, one two Check it out y'all Uhh, shadz of lingo in the house E double's in the house with def squad On the funky fresh track with shadz of lingo Mic check one two, yo you got my nerves jumpin around And _humpin' around_ like bobby brown across town I ain't with that, so don't cramp my style Step off me, I'm hyped like I had a pound of coffee Yo how could you ask what I'm doin When I'm pursuin, gettin funky with my crew and My input brings vibes unknown like e.t. Makes me phone home to my family Cling, hello mom, I'm doin it, freakin more fame Than batman played by michael keaton I crossed over, let me name someone that's black With fame, and pockets that are fat Heyyy, erick sermon, he's one Packs a gun, that's bigger than malcolm's Out the window, I look for a punk to get stupid So I can shoot his ass like cupid E 2 bingos, down with the shadz of lingo Here to bust out the funky single Ahh shit, there goes my pager I'll see you later, because yo Every now and then, I get a little crazy One two how can I do it? I guess I'll spit the real Yo I pack much dick, with the cover made of steel hoe Yes yes, never fessed or settled for less One clown stepped, and got a hole in the fuckin chest From the a.k., somebody scream mayday Took the sucker out, cause he clowned me on a payday The funk is flowin to the maximum From the e double, while I kick the facts to them Check a chill brother with class, rough enough To run up and snatch the spine out a niggaz ass Grip the steel when caps peeled, here to chill -

Hip Hop Pedagogies of Black Women Rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers Nichole Ann Guillory Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Guillory, Nichole Ann, "Schoolin' women: hip hop pedagogies of black women rappers" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 173. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/173 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SCHOOLIN’ WOMEN: HIP HOP PEDAGOGIES OF BLACK WOMEN RAPPERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Nichole Ann Guillory B.S., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette, 1998 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Nichole Ann Guillory All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Linda Espree and my grandmother Lovenia Espree iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled by the continuous encouragement and support I have received from family, friends, and professors. For their prayers and kindness, I will be forever grateful. I offer my sincere thanks to all who made sure I was well fed—mentally, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I would not have finished this program without my mother’s constant love and steadfast confidence in me. -

The E Book 2021–2022 the E Book

THE E BOOK 2021–2022 THE E BOOK This book is a guide that sets the standard for what is expected of you as an Exonian. You will find in these pages information about Academy life, rules and policies. Please take the time to read this handbook carefully. You will find yourself referring to it when you have questions about issues ranging from the out-of-town procedure to the community conduct system to laundry services. The rules and policies of Phillips Exeter Academy are set by the Trustees, faculty and administration, and may be revised during the school year. If changes occur during the school year, the Academy will notify students and their families. All students are expected to follow the most recent rules and policies. Procedures outlined in this book apply under normal circumstances. On occasion, however, a situation may require an immediate, nonstandard response. In such circumstances, the Academy reserves the right to take actions deemed to be in the best interest of the Academy, its employees and its students. This document as written does not limit the authority of the Academy to alter its rules and procedures to accommodate any unusual or changed circumstances. If you have any questions about the contents of this book or anything else about life at Phillips Exeter Academy, please feel free to ask. Your teachers, your dorm proctors, Student Listeners, and members of the Dean of Students Office all are here to help you. Phillips Exeter Academy 20 Main Street, Exeter, New Hampshire Tel 603-772-4311 • www.exeter.edu 2021 by the Trustees of Phillips Exeter Academy HISTORY OF THE ACADEMY Phillips Exeter Academy was founded in 1781 A gift from industrialist and philanthropist by Dr. -

Libraryonwheels Sparksinterest

EMI Records Aligns with Erick Sermon and Def Squad Label EMI Records (EMI have always wanted for Def /Chrysalis /SBK) today Squad Records. announced a label agreement with 1 look forward to working Def Squad Records, led with Davitt by rap recording artist/producer Sigerson and the Erick whole EMI team and to having Sermon. Under this a arrangement. Sermon will very successful'relationship submit artists together." exclusively to Sermon first made his mark EMI who concentrate on devel¬ in and the rap community as half of oping producing new the classic EPMD combo. Teachers from the Bethlehem Hills ~~HFhas since Released two Happy Child Care Center brouse through the Smart Start Bookmobile. label and will continue produc¬ solo Teachers selected books for students in their class. Keith albums. No Pressure and ing Redman, Murray and Double or other established artists. Nothin' on Def Jam Def In addition to and Squad will have offices and a finding pro¬ y ducing new talent, staff based out of the EMI including On Wheels New Das EFX, Redman and Keith Library Interest York Headquarters. * By MAURICE CROCKER Sparks Murray, Sermon has also chosen for the bookmobile are Commented Davitt pro¬ Community News Reporter The first stop of the book¬ Siger- duced singles for a diverse selected by the library heads at mobile was the son, president and CEO, EMI of each Bethlehem "Erick array artists such as Super- The branch. Happy Hills Child Care Center. Records, is always cat, Blackstreet, Forsyth County Some of the books are focused or His record Shaquille Library has started a new cho¬ "I think this is a good quality. -

Funk the Clock: Transgressing Time While Young, Prescient and Black A

Funk the Clock: Transgressing Time While Young, Prescient and Black A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Rahsaan Mahadeo IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisers: David Pellow and Joyce Bell August 2019 © 2019 Rahsaan Mahadeo Acknowledgements Pursuing a PhD has at times felt like the most selfish endeavor I have ever undertaken. For I knew that every book I read and every paper I wrote was largely for personal gain. Not coming from academic lineage or economic privilege, I could not escape the profound sense of guilt of leaving so many behind in the everyday struggle to live, labor and learn in a school that is less of a land-grant institution and more of a land-grab institution; an educational system that is more private than public; a corporation that presents students with more educational opportunists than educational opportunities; a sea of scholarship that looks more like colonizer ships; and a tower that is as anti ebony as it is ivory. Most know it as the “U of M,” when it is really the U of empire. Here, I would like to take the opportunity to counter the university’s individualistic and neoliberal logic to thank several people who have helped me cope with the challenges of living, learning and laboring in a space designed without me (and many others) in mind. Thank you to my advisers David Pellow and Joyce Bell for supporting me along my graduate school journey. Though illegible to the university, I recognize and appreciate the inordinate amount of labor you perform inside and outside the classroom. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

Człowiek Który Spaja Hip Hop Christopher Edward Martin Znany

Człowiek który spaja hip hop Christopher Edward Martin znany jednak bardziej pod pseudonimem Dj Premier(ur. 21 marca 1966 roku) to ameryka ński producent i Dj hip-hopowy. Wraz z raperem Guru tworzył grup ę Gang Starr. Urodził si ę w Houston, lecz w bardzo młodym wieku przeprowadził si ę na Brooklyn. Pocz ątek kariery Chris Martin zacz ął interesowa ć si ę DJk ą w okresie ucz ęszczania do szkoły Prairie View A&M w Prairie View w stanie Texas. Na pocz ątku wyst ępował pod pseudonimem Waxmaster C, ale zmienił go na DJ Premier po przeprowadzce na Brooklyn i razem z Guru reaktywował zespół Gang Starr. Wybrał pseudonim Premier, poniewa ż chciał by ć pierwszym w tym fachu. Gang Starr Grupa została zało żona w 1988 roku w Bostonie. Debiutancki album „No More Mr. Nice Guy” został nagrany w ci ągu 10 dni i był to nie lada wyczyn. Nast ępne albumy przynosiły jeszcze wi ększe sukcesy i sław ę. Ostatni album został wydany w 2003 roku „ The Ownerz”. Albumy ekipy Gang Starr dzi ś uchodz ą za czyst ą klasyk ę i co do tego nie ma wi ększych w ątpliwo ści, s ą to albumy, które potrafiły si ę przebi ć ponad kr ąż ki innych znakomitych artystów tworz ących w tych czasach. Pokazuje to nam, że oprawa muzyczna, za któr ą był odpowiedzialny Premier na tych płytach, była magiczna i zapadaj ąca w pami ęć . Grupa została rozwi ązana w 2005 roku, a drugi członek zespołu Guru zmarł w roku 2010. Współpraca Je żeli zapytaliby śmy jakiego ś muzyka, mc o to, czy chciałby współpracowa ć z Dj premierem, pewnie bez wahania by si ę zgodził i raczej nie byłaby to zaskakuj ąca odpowied ź, poniewa ż kiedy taki muzyk patrzy na list ę artystów, którym było dane z nim współpracowa ć, wie, że praca z takim człowiekiem gwarantuje robienie muzyki na najwy ższym poziomie. -

U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual, 2008

U.S. Government Printing Offi ce Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government printing 2008 PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd i 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:040:18:04 AAMM Production and Distribution Notes Th is publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. Th e GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To fi nd a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. Th e electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/stylemanual/index.html. Use of ISBN Prefi x Th is is the offi cial U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identifi ed to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978–0–16–081813–4 is for U.S. Government Printing Offi ce offi cial editions only. Th e Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Offi ce requests that any re- printed edition be labeled clearly as a copy of the authentic work, and that a new ISBN be assigned. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001 ISBN 978-0-16-081813-4 (CD) II PPreliminary-CD.inddreliminary-CD.indd iiii 33/4/09/4/09 110:18:050:18:05 AAMM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE STYLE MANUAL IS PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION AND AUTHORITY OF THE PUBLIC PRINTER OF THE UNITED STATES Robert C. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

Missy Elliott Supa Dupa Fly Torrent Download Supa Dupa Fly

missy elliott supa dupa fly torrent download Supa Dupa Fly. Arguably the most influential album ever released by a female hip-hop artist, Missy "Misdemeanor" Elliott's debut album, Supa Dupa Fly, is a boundary-shattering postmodern masterpiece. It had a tremendous impact on hip-hop, and an even bigger one on R&B, as its futuristic, nearly experimental style became the de facto sound of urban radio at the close of the millennium. A substantial share of the credit has to go to producer Timbaland, whose lean, digital grooves are packed with unpredictable arrangements and stuttering rhythms that often resemble slowed-down drum'n'bass breakbeats. The results are not only unique, they're nothing short of revolutionary, making Timbaland a hip name to drop in electronica circles as well. For her part, Elliott impresses with her versatility -- she's a singer, a rapper, and an equal songwriting partner, and it's clear from the album's accompanying videos that the space-age aesthetic of the music doesn't just belong to her producer. She's no technical master on the mic; her raps are fairly simple, delivered in the slow purr of a heavy-lidded stoner. Yet they're also full of hilariously surreal free associations that fit the off-kilter sensibility of the music to a tee. Actually, Elliott sings more on Supa Dupa Fly than she does on her subsequent albums, making it her most R&B-oriented effort; she's more unique as a rapper than she is as a singer, but she has a smooth voice and harmonizes well. -

Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. V. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 45 | Issue 2 Article 4 1-1994 Thou hS alt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music Carl A. Falstrom Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Carl A. Falstrom, Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music, 45 Hastings L.J. 359 (1994). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol45/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thou Shalt Not Steal: Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc. and the Future of Digital Sound Sampling in Popular Music by CARL A. FALSTROM* Introduction Digital sound sampling,1 the borrowing2 of parts of sound record- ings and the subsequent incorporations of those parts into a new re- cording,3 continues to be a source of controversy in the law.4 Part of * J.D. Candidate, 1994; B.A. University of Chicago, 1990. The people whom I wish to thank may be divided into four groups: (1) My family, for reasons that go unstated; (2) My friends and cohorts at WHPK-FM, Chicago, from 1986 to 1990, with whom I had more fun and learned more things about music and life than a person has a right to; (3) Those who edited and shaped this Note, without whom it would have looked a whole lot worse in print; and (4) Especially special persons-Robert Adam Smith, who, among other things, introduced me to rap music and inspired and nurtured my appreciation of it; and Leah Goldberg, who not only put up with a whole ton of stuff for my three years of law school, but who also managed to radiate love, understanding, and support during that trying time.