Morton Feldman's for Samuel Beckett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morton Feldman: a Celebration of His 80Th Birthday

Morton Feldman : A Celebration of His 80th Birthday Curated by John Bewley June 1 – September 15, 2006 Case 1 Morton Feldman was born January 12, 1926 in New York City to Irving and Frances Feldman. He grew up in Woodside, Queens where his father established a company that manufactured children’s coats. His early musical education consisted of piano lessons at the Third Street Settlement School in Manhattan and beginning at age twelve, with Vera Maurina Press, an acquaintance of the Russian composer, Alexander Scriabin, and a student of Ferruccio Busoni, Emil von Sauer, and Ignaz Friedman. Feldman began composing at age nine but did not begin formal studies until age fifteen when he began compositional studies with Wallingford Riegger. Morton Feldman, age 13, at the Perisphere, New York World’s Fair, 1939? Unidentified photographer Rather than pursuing a college education, Feldman chose to study music privately while he continued working for his father until about 1967. After completing his studies in January 1944 at the Music and Arts High School in Manhattan, Feldman studied composition with Stefan Wolpe. It was through Wolpe that Feldman met Edgard Varèse whose music and professional life were major influences on Feldman’s career. Excerpt from “I met Heine on the Rue Furstenburg”, Morton Feldman in conversation with John Dwyer, Buffalo Evening News, Saturday April 21, 1973 Let me tell you about the factory and Lukas Foss (composer and former Buffalo Philharmonic conductor). The plant was near La Guardia airport. Lukas missed his plane one day and he knew I was around there, so he called me up and invited me to lunch. -

Feldman the Rug-Maker, Weaving for John Cage by Meg Wilhoite

Feldman the Rug-maker, Weaving For John Cage By Meg Wilhoite In an interview with Jan Williams, Morton Feldman described his fascination with ancient Middle Eastern patterned rugs: “In older oriental rugs the dyes are made in small amounts and so what happens is that there is an imperfection throughout the rug of changing colors of these dyes. Most people feel that they are imperfections. Actually it is the refraction of the light on these small dye batches that makes the rugs wonderful. I interpreted this as going in and out of tune. There is a name for that in rugs - it's called abrash - a change of colors that leads us into pieces like Instruments III [1977] which was the beginning of my rug idea.”1 There is an intimate connection between the rugs Feldman admired and many of the pieces he wrote in the last fifteen or so years of his life. These rugs set up an overall effect of sameness by systematically repeating a set of patterns, while at the same time disrupting this effect by slightly altering the components of those patterns. Similarly, Feldman wrote long works that produce a sense of skewed sameness by writing musical patterns that repeat many times, but change in intonation and/or rhythm almost imperceptibly. I present here a picture of Feldman as meticulous rug-maker, as he wove together what pianist Siegfried Mauser referred to as “an image of discreetly arranged musical sound and form.”2 Thinking of Feldman’s lengthy late works in terms of rug weaving provides us with a useful framework on which to hang both small and large-scale analyses of his music. -

Notes on Morton Feldman's “The King of Denmark” by Eberhard Blum

Notes on Morton Feldman’s “The King of Denmark” by Eberhard Blum [English translation by Peter Söderberg] In February and March 2008 I had an exhibition, entitled “Choice & Chance”, at the Villa Oppenheim in Berlin, a centre for contemporary art. This featured some forty of my large graphite works on paper. In connection with the exhibition, the percussionist Adam Weisman gave a concert with the following programme: Morton Feldman – The King of Denmark (1964), first realization Karlheinz Stockhausen – Zyklus for a percussionist (1959) Morton Feldman – The King of Denmark (1964), second realization I have been familiar with both these compositions for a long time. Their principles of construction have influenced many considerations affecting the construction of my own graphic work (e.g., the question: What could be the nature of indeterminate or aleatoric graphic works?). Morton Feldman often talked about his piece and also described its relationship to Stockhausen’s. Through the percussionist Jan Williams I came to know Feldman’s piece in detail. During his tenure at the “Center of the Creative and Performing Arts” in Buffalo, Jan had created a version which fully corresponded to Feldman’s own conception of the work. The choice of percussion instruments, which are not determined in the score, was made by Jan according to Feldman’s proposals and wishes. More than once I observed them both in the famous percussion room – Room 100 of the Music Department at the University, where early in 1978 we first performed Feldman’s work “Why Patterns?”, then still called “Instruments 4”, for his students – the two of them comparing the sounds of small cymbals and triangles to make the right decision. -

Solo Percussion Is Published Ralph Shapey by Theodore Presser; All Other Soli for Solo Percussion

Tom Kolor, percussion Acknowledgments Recorded in Slee Hall, University Charles Wuorinen at Buffalo SUNY. Engineered, Marimba Variations edited, and mastered by Christopher Jacobs. Morton Feldman The King of Denmark Ralph Shapey’s Soli for Solo Percussion is published Ralph Shapey by Theodore Presser; all other Soli for Solo Percussion works are published by CF Peters. Christian Wolff Photo of Tom Kolor: Irene Haupt Percussionist Songs Special thanks to my family, Raymond DesRoches, Gordon Gottlieb, and to my colleagues AMERICAN MASTERPIECES FOR at University of Buffalo. SOLO PERCUSSION VOLUME II WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1578 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2015 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. AMERICAN MASTERPIECES FOR AMERICAN MASTERPIECES FOR Ralph Shapey TROY1578 Soli for Solo Percussion SOLO PERCUSSION 3 A [6:14] VOLUME II [6:14] 4 A + B 5 A + B + C [6:19] Tom Kolor, percussion Christian Wolf SOLO PERCUSSION Percussionist Songs Charles Wuorinen 6 Song 1 [3:12] 1 Marimba Variations [11:11] 7 Song 2 [2:58] [2:21] 8 Song 3 Tom Kolor, percussion • Morton Feldman VOLUME II 9 Song 4 [2:15] 2 The King of Denmark [6:51] 10 Song 5 [5:33] [1:38] 11 Song 6 VOLUME II • 12 Song 7 [2:01] Tom Kolor, percussion Total Time = 56:48 SOLO PERCUSSION WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1578 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. TROY1578 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

A Musical Work Emerges and Disappears – Morton Feldman's The

A musical work emerges and disappears – Morton Feldman’s The Possibility of a New Work for Electric Guitar 1 by Peter Söderberg The Possibility of a New Work for Electric Guitar is a work by Morton Feldman that does not exist. Or maybe it does, after all! There was certainly something resembling a work for one year, between 1966 and 1967, after which all traces seemed to disappear. But can an existing musical work really cease to be, and if so, under what conditions? Can a work reappear after many years, in spite of the fact that the original, the composer’s manuscript, is lost? Morton Feldman composed The Possibility of a New Work for Electric Guitar in early 1966, at the request of his colleague Christian Wolff. Feldman and Wolff were since the early 1950’s part of the circle around John Cage in New York, and they both belong amongst the most the prominent American composers of the second half of the 20th century. Less well- known is the fact that, around that time, Christian Wolff performed as an electric guitar player. He played the instrument without any real training and with an idiosyncratic technique, often with the guitar lying on the floor or on a table. Wolff has testified that the music emerged on a single occasion, when he and Feldman got together. Feldman sat at the piano, playing sounds that Wolff would try to transfer to the guitar. The result of the investigation was notated by Feldman, and in that way the work took shape. On the same occasion, Feldman handed over the sheet music to Wolff, and accordingly the work was established in the form that would be the ultimate – at least from the composer’s pen. -

Suspicious Silence: Walking out on John Cage

Suspicious Silence: Walking Out on John Cage Clark Lunberry “What we require is / silence; but what silence requires / is that I go on talking .” –John Cage, “Lecture on Nothing” “Well, shall we / think or listen? Is there a sound addressed / not wholly to the ear?” –William Carlos Williams, “The Orchestra” Critical Innocence: 2012 marked what would have been the composer and writer John Cage’s 100th birthday, offering a nice round numbered moment to commemorate and reevaluate Cage’s lasting legacy. And it is a rich and still, astonishingly, controversial legacy, bringing forth bold assessments of Cage that range, as they have for decades, from worshipful acclaim, to ridiculing rejection. It seems with Cage, still, that it’s either black or white, love or hate; that he is either a saintly prophet of new sounds, new silences, or a foolish charlatan leading anarchically astray. Of late, however, one reads more and more critical accounts of Cage that, while acknowledging his wide–ranging influence and importance, suggest nonetheless of him a deafening innocence to his own renowned hearing. A new generation of writers and listeners, one that is perhaps more theoretically inclined and less reverential of the composer’s acclaim, have begun to raise questions about what they perceive as the unexamined dimensions of some of Cage’s claims about silence, the nature of the nothing that was thought to have constituted it. Cage, as a consequence, is now often more mystically presented as somewhat naively espousing a kind of zen–like syncing of a scene with a sound, with its immediate moment. -

Morton Feldman and Abstract Expressionism

Morton Feldman and Abstract Expressionism Time and sound construction in his piano miniatures of the 1950s and 1960s by Gianmario Borio (English translation by Francesco Sani) This essay was first published in Italian in Itinerari della musica americana, edited by Gianmario Borio and Gabrio Taglietti, Lucca, Lim 1996, pp. 119-134. An earlier version appeared as a chapter in Borio’s PhD dissertation Musikalische Avantgarde um 1960. Entwurf einer Theorie der informellen Musik, Laaber Verlag, Laaber 1993, pp. 146-167. The circle of musicians gathering around John Cage towards the latter part of the 1940s – Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, David Tudor and Christian Wolff – expressed a strong interest in the visual arts. Cage, right from the time of his studies with Arnold Schoenberg in 1935, had taken an interest in abstract painting – Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian – and had himself begun painting. The most fruitful encounter for him was with Mark Tobey at the Cornish School of Art in Seattle; the latter’s white paintings suggested to Cage the idea of non-representational and radically abstract art[1]. Perhaps it was after meeting Cage in 1941 that Tobey began studying piano and composition. His fascination with music concerned especially rhythmic and contrapuntal aspects, the subject of his paintings – stars, swarming lights, crowds and urban landscapes – executed through several interacting lines giving life to an experience characterised by an overall rhythmic pulse[2]. Tobey worked in the West Coast, an area that more than any other in the US was influenced by Asian philosophy and religion. This cultural background helps understanding the intellectual affinity felt http://www.cnvill.net/mfborio.pdf 1 by Cage when confronted with Tobey’s work. -

Morton Feldman in Conversation with Stuart Morgan the Following

Pie-Slicing and Small Moves: exemplified in the twentieth century by Mondrian. Tact informs Feldman's art criticism, which is Morton Feldman in conversation with Stuart meditative, daring and partisan. (See, for example, Morgan "Some Elementary Questions" Art News April 1967; "After Modernism" Art in America December 1971; "The Anxiety of Art" Art in The following interview was originally published in America September-October 1973.) A heightened Artscribe (April 1978) pp 34-37. sensitivity to time and the gradual progression of artistic careers underlies both his reminiscences "I don't know what a composer is," said Morton ("Give my Regards to Eighth Street" Art in Feldman two years ago. "I never knew as a young America March-April 1971) and an eloquent man, I don't know now and I'm gonna be fifty tribute to his friend Frank O'Hara ("Frank next month." Feldman (at present Edgar Varèse O'Hara: Lost Times and Future Hopes" Art in Professor of Music at the State University of New America March-April 1972). Preoccupation with York at Buffalo) studied composition with images of life and death is evident in his images of Wallingford Riegger and Stefan Wolpe. In New creative work. "What it really amounts to is York in the fifties he met John Cage and joined a whether you want to be in the work, in the circle that included Earle Brown, Christian Wolff medium or outside it . I feel that Cage and and pianist David Tudor. A second major myself are in the work . Stockhausen and influence was painting; friendships with Rothko, Boulez are out of it". -

Between Categories-Morton Feldman

Contemporary Music Review ISSN: 0749-4467 (Print) 1477-2256 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcmr20 Between categories Morton Feldman To cite this article: Morton Feldman (1988) Between categories, Contemporary Music Review, 2:2, 1-5, DOI: 10.1080/07494468808567063 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494468808567063 Published online: 10 Oct 2011. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 120 View related articles Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gcmr20 Download by: [Royal Conservatoire of Scotland], [Maria Donohue] Date: 26 September 2016, At: 05:04 Contemporary Music Review, © 1988 Harwood Academic Publishers GmbH 1988, Vol. 2 pp. 1-5. Printed in the-United Kingdom Photocopying permitted by license only Between categories Morton Feldman This article was originally published in the mimeographed periodical The Composer (Vol. 1, no. 2, 1969, pp. 73-77). Almost immediately it was translated into Swedish ("Mellan kategoriema," Nutida Musik, vol. 12, no. 4, 1968-69, pp. 25-27) and French ("Entre des categories," Musique en Jeu, No. 1, 1970, pp. 22-26). More recently it has appeared in a German re-translation from the Swedish and French versions in the collection of Feldman's writings edited by Walter Zimmermann ("Zwischen den Kategorien," in Morton Feldman: Essays. Kerpen, Beginner Press, 1985, pp. 82-84). This is the first time Feldman's original text, which is rather hard to find, has been reprinted. KEY WORDS music, painting, construction, surface. Space, Time. Oscar Wilde tells us that a painting can be interpreted in two ways, by its subject or by its surface. -

David Tudor in Darmstadt Amy C

This article was downloaded by: [University of California, Santa Cruz] On: 22 November 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 923037288] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Music Review Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713455393 David Tudor in Darmstadt Amy C. Beal To cite this Article Beal, Amy C.(2007) 'David Tudor in Darmstadt', Contemporary Music Review, 26: 1, 77 — 88 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/07494460601069242 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494460601069242 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Contemporary Music Review Vol. 26, No. 1, February 2007, pp. 77 – 88 David Tudor in Darmstadt1 Amy C. -

Musical Rhetoric, Narrative, Drama, and Their Negation in Morton Feldman's Piano and String Quartet

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Musical Rhetoric, Narrative, Drama, and Their Negation in Morton Feldman's Piano and String Quartet Ryan Michael Howard Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/487 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSICAL RHETORIC, NARRATIVE, DRAMA, AND THEIR NEGATION IN MORTON FELDMAN’S PIANO AND STRING QUARTET by Ryan M. Howard A dissertation submitted to the Department of Music of the Graduate Center, City University of New York in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 © Ryan M. Howard, 2014 All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Dr. Jeff Nichols, Advisor Dr. Joseph Straus, First Reader Dr. David Olan Dr. Bruce Saylor Dr. Nils Vigeland supervisory committee iii Abstract Musical Rhetoric, Narrative, Drama, and Their Negation in Morton Feldman’s Piano and String Quartet by Ryan Howard Advisor: Dr. Jeff Nichols Though Morton Feldman famously expressed his aversion to conventional compositional rhetoric early in his career, an examination of his music from the late 1970s onward reveals a more complex and ambiguous relationship with musical rhetoric than has often been acknowledged. -

Programme Notes

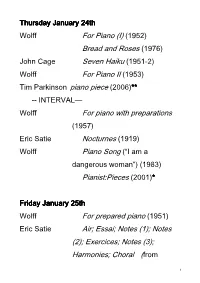

Thursday January 24th Wolff For Piano (I) (1952) Bread and Roses (1976) John Cage Seven Haiku (1951-2) Wolff For Piano II (1953) Tim Parkinson piano piece (2006)****** -- INTERVAL— Wolff For piano with preparations (1957) Eric Satie Nocturnes (1919) Wolff Piano Song (“I am a dangerous woman”) (1983) Pianist:Pieces (2001) *** Friday January 25th Wolff For prepared piano (1951) Eric Satie Air; Essai; Notes (1); Notes (2); Exercices; Notes (3); Harmonies; Choral (from 1 'Carnet d'esquisses et do croquis', 1900-13 ) Wolff A Piano Piece (2006) *** Charles Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) Steve Chase Piano Dances (2007-8) ****** Wolff Accompaniments (1972) --INTERVAL— Wolff Eight Days a Week Variation (1990) Cornelius Cardew Father Murphy (1973) Howard Skempton Whispers (2000) Wolff Preludes 1-11 (1980-1) Saturday January 26th Christopher Fox at the edge of time (2007) *** Wolff Studies (1974-6) Michael Parsons Oblique Pieces 8 and 9 (2007) ****** 2 Wolff Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida (1979) --INTERVAL-- Wolff Suite (I) (1954) For pianist (1959) Webern Variations (1936) Wolff Touch (2002) *** (** denotes world premiere; *** denotes UK premiere) for pianist: the piano music of Christian Wolff Given the importance within Christian Wolff’s compositional aesthetic of music which involves interaction between players, it is perhaps surprising that there is a significant body of works for solo instrument. In particular the piano proves to be central 3 to Wolff’s output, from the early 1950s to the present day. These concerts include no fewer than sixteen piano solos; I have chosen not to include a number of other works for indeterminate instrumentation which are well suited to the piano (the Tilbury pieces for example) as well as two recent anthologies of short pieces, A Keyboard Miscellany and Incidental Music , and also Long Piano (Peace March 11) of which I gave the European premiere in 2007.