Saleem Yousuf (Pakistan 1982 to 1990)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware Milestones

DECIDE: How to Manage the Risk in Your Decision Making Beware milestones Having convinced you to improve your measurement of what really matters in your organisation so that you can make better decisions, I must provide a word of caution. Sometimes when we introduce new measures we actually hurt decision making. Take the effect that milestones have on people. Milestones as the name infers are solid markers of progress on a journey. You have either made the milestone or you have fallen short. There is no better example of the effect of milestones on decision making than from sport. Take the game of cricket. If you don’t know cricket all you need to focus in on is one number, 100. That number represents a century of runs by a batsman in one innings and is a massive milestone. Careers are judged on the number of centuries a batsman scores. A batsman plays the game to score runs by hitting a ball sent toward him at varying speeds of up to 100.2 miles per hour (161.3 kilometres per hour) by a bowler from 22 yards (20 metres) away. The 100.2 mph delivery, officially the fastest ball ever recorded, was delivered by Shoaib Akhtar of Pakistan. Shoaib was nicknamed the Rawalpindi Express! Needless to say, scoring runs is not dead easy. A great batting average in cricket at the highest levels is 40 plus and you are among the elite when you have an average over 50. Then there is Australia’s great Don Bradman who had an average of 99.94 with his next nearest rivals being South Africa’s Graeme Pollock with 60.97 and England’s Herb Sutcliffe with 60.63. -

Newsletter June 2021

–- 1 President Arif Alvi promotes research-oriented and innovation-based quality education in universities resident Dr Arif Alvi has called for promoting research-oriented and innovation-based quality P education in universities to overcome the scientific and technological challenges faced by the country. He emphasised the need to educate the students about the latest technological trends in order to meet the requirements of the 4th Industrial Revolution. The President made these remarks at a briefing on Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), given by Rector LUMS, Mr Shahid Hussain, at Aiwan-e-Sadr, on June 14, 2021. Addressing the meeting, the Presi- dent underlined the need for promotion of online education as it was cost-effective and accessible to students belonging to the far flung areas of the country and under-privileged strata of society. He urged the universities to initiate steps to encourage e-learning as it played an instrumental role in ensuring continuity of education during the COVID-19 pandemic. President condoles with family killed in terrorist attack in Canada’s London Ontario resident Dr Arif Alvi and Begum Samina Alvi P visited the resi- dence of bereaved family of Pakistani origin victims of the terrorist attack in Ontario, Canada, to express their condolence. The president expressed his sympathies with the bereaved family over the loss, a press release said. The president and Begum Alvi offered Fateha and prayed for the departed soul and for the bereaved family to bear the loss with equanimity. 2 Prime Minister Imran Khan urges world leaders to act against Islamophobia rime Minister Imran Khan has called upon the world P leaders to crack down on online hate speech and Islamophobia following the deadly truck attack in London, Ontario, Canada. -

Will T20 Clean Sweep Other Formats of Cricket in Future?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Subhani, Muhammad Imtiaz and Hasan, Syed Akif and Osman, Ms. Amber Iqra University Research Center 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/45144/ MPRA Paper No. 45144, posted 16 Mar 2013 09:41 UTC Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Muhammad Imtiaz Subhani Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Amber Osman Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Syed Akif Hasan Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 1513); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Bilal Hussain Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Abstract Enthralling experience of the newest format of cricket coupled with the possibility of making it to the prestigious Olympic spectacle, T20 cricket will be the most important cricket format in times to come. The findings of this paper confirmed that comparatively test cricket is boring to tag along as it is spread over five days and one-days could be followed but on weekends, however, T20 cricket matches, which are normally played after working hours and school time in floodlights is more attractive for a larger audience. -

RBBA Coaches Handbook

RBBA Coaches Handbook The handbook is a reference of suggestions which provides: - Rule changes from year to year - What to emphasize that season broken into: Base Running, Batting, Catching, Fielding and Pitching By focusing on these areas coaches can build on skills from year to year. 1 Instructional – 1st and 2nd grade Batting - Timing Base Running - Listen to your coaches Catching - “Trust the equipment” - Catch the ball, throw it back Fielding - Always use two hands Pitching – fielding the position - Where to safely stand in relation to pitching machine 2 Rookies – 3rd grade Rule Changes - Pitching machine is replaced with live, player pitching - Pitch count has been added to innings count for pitcher usage (Spring 2017) o Pitch counters will be provided o See “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook - Maximum pitches per pitcher is 50 or 2 innings per day – whichever comes first – and 4 innings per week o Catching affects pitching. Please limit players who pitch and catch in the same game. It is good practice to avoid having a player catch after pitching. *See Catching/Pitching notations on the “Pitch Limits & Required Rest Periods” at end of Handbook. - Pitchers may not return to game after pitching at any point during that game Emphasize-Teach-Correct in the Following Areas – always continue working on skills from previous seasons Batting - Emphasize a smooth, quick level swing (bat speed) o Try to minimize hitches and inefficiencies in swings Base Running - Do not watch the batted ball and watch base coaches - Proper sliding - On batted balls “On the ground, run around. -

PEAK PERFORMANCE AGE: a DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS of PAKISTAN TEST BATSMEN Imran Abbass

PEAK PERFORMANCE AGE: A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF PAKISTAN TEST BATSMEN Imran Abbass ABSTRACT The study intended to explore the relationship of age and performance of test batsmen to know at what age they achieved the peak performance while playing test cricket. Qualitative data was collected through interviews and Secondary data sources were used of different ICC (International Cricket Council) websites and magazines. Sample comprised of top 12 test players of Pakistan from past and present era, who played for Pakistan with distinction. Time series and regression analysis was executed to find the significance of the relationship between their age and performance (Batting average).The findings of the study revealed a parabolic trajectory relationship between age and their performance, positive relationship at the start and then a plateau and then a negative relationship between age and performance. The rise and decline pattern varied and majority of the cricket players touched the peak between the ages of 28 to 34 years. The current study will provide solid grounds to account the role of age in producing expert performance and strongly suggested through the evidence of data analysis that to achieve the expert performance of the enrolled test batsmen, patience is required until and unless the cricket players meet a specific age limit. Key Words: Cricket, Test Batsmen, Peak Performance, Age INTRODUCTION score of 23, Aamer nicked one to On a bright sunny morning of the Bacher in the slips and in 1997-98 winters, stage was set to adding four runs Pakistan top topple the mighty South Africans four batsman were gone to the at eastern shores. -

PCB Annual Report 2018-19

Designed by PRESTIGE Annual Report 2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 Contents Foreword Men's domestic cricket Chairman's Report 1 Regional Inter-District 2018-2019 65 Managing Director's Report 4 Quaid-e-Azam Trophy 67 Overview of men's international cricket 5 Quaid-e-Azam Trophy Grade-II 69 Overview of women’s international/domestic cricket 7 One-Day Cup for Regions and Departments 71 Overview of men's domestic cricket 9 Quaid-e-Azam One-Day Cup 73 Overview of women’s game development 11 National T20 Cup 75 Overview of the Academies' programmes 13 HBL PSL 2019 77 Obituaries 16 Pakistan Cup 83 Patron's Trophy Grade-II 85 Men's international cricket (2018-2019) Women's domestic cricket Asia Cup 2018 19 Inter-Departmental T20 Women's Cricket Championship 89 Pakistan vs Australia in the UAE 21 PCB Triangular One-Day Women’s Cricket Tournament 2018-19 91 Pakistan vs New Zealand in the UAE 25 Pakistan in South Africa 27 Pathways cricket Pakistan in England 31 U13 Regional National T20 Tournament 95 U16 Regional National One-Day Tournament 97 Men's international cricket U16 Pentangular One-Day Tournament 99 (2017-2018) Inter-Region U19 Three-Day Tournament 101 Independence Cup 2018 Pakistan vs World XI 35 Inter-Region U19 One-Day Tournament 103 Pakistan vs Sri Lanka in the UAE and Lahore 37 Pentangular U19 T20 Cup 105 Pakistan in New Zealand 39 Pakistan A vs New Zealand A and England Lions in the UAE 106 West Indies in Karachi 41 Pakistan U16 vs Australia U16 in the UAE 109 Pakistan tour of Ireland, England and Scotland 43 Pakistan U16 in Bangladesh -

Download Detailed Profiles

Profiles Department of Electrical Engineering 194 | P a g e www.ist.edu.pk Class of 2021 Message from the Head of Department Department of Electrical Engineering is one of the most active and productive departments at IST. We pride in having the most vibrant faculty and well- groomed multidimensional students driven by self- motivation and quest to continuously improve. We already have a well- established degree program in Electrical Engineering and from Fall 2020, the department has also started the degree program in Computer Science which has now become one of the most sought-after and premier career choice world-wide. Our department offers one of the field’s strongest instructional and research program driven in part by the industry. We have very strong linkages with both public sector as well private sector industry that results in meaningful projects and research. Our graduates have got jobs in big international companies like CERN, AirBus, Huawei, Eltek etc. and almost all renowned national firms including defense sector. Our graduates have won competitive MS/PhD scholarships in world's top schools including Columbia USA, BYU USA, RWTH Aachen Germany, York Canada, Cambridge UK, NTNU Norway and Monash Australia to name a few. I have always got very positive feedback from employers as well as foreign professors about our graduates and that always makes me and our faculty very happy. Unlike most other disciplines, career opportunities in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science are endless as graduates can work anywhere from startups to big tech firms and government agencies. With the world's focus on miniaturized electronics coupled with computer vision & artificial intelligence, both degree programs offered at department of electrical engineering at IST will prepare you for a bright future. -

One Year In: a Conversation with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan

1 One Year In: A Conversation with Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan United States Institute of Peace Tuesday, July 23, 2019 Transcript Nancy Lindborg: Good morning, everybody. My name is Nancy Lindborg. I'm the president and CEO here at the U.S. Institute of Peace, and I'm delighted to welcome you here today. A special welcome to our esteemed guest of honor, Prime Minister Imran Khan, and to the delegation who's traveled far to be here with him. A warm welcome to every who's joining us online, and you can join the conversation @USIP on Twitter with #ImranKhanUSIP. And I'm delighted everyone could be here for the conversation today. This is the kind of conversation that is the hallmark of U.S. Institute of Peace, which was founded 35 years ago by Congress as an independent, nonpartisan national institution dedicated to reducing international violent conflict. And, we very strongly believe that peace is possible, that peace is practical, and it is absolutely essential for U.S. and international security. So, we pursue our mission by linking research with policy, with training and with action, working on the ground with partners. Our Pakistan program is one of our largest here at the Institute, and we've been active in the country since 2011. We partner with a network of civil society organizations, innovators, scholars and policymakers to support local programs, conduct research and analysis and convene local peacebuilders. We've supported programs in cities and villages throughout Pakistan. We focus on increasing tolerance of diversity using arts, media and culture to promote dialogue and peace education. -

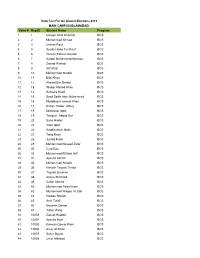

Voter # Reg ID Student Name Program 1 1 Haroon Afzal Khokhar

Voter List For Air Alumni Elections 2019 MAIN CAMPUS(ISLAMABAD) Voter # Reg ID Student Name Program 1 1 Haroon Afzal Khokhar BCS 2 2 Muhammad Ahmed BCS 3 3 Usman Rauf BCS 4 5 Syeda Hibba Tur-Rauf BCS 5 6 Hureen Fatima Qureshi BCS 6 7 Sardar Muhammad Murtaza BCS 7 8 Zainab Wahab BCS 8 9 Atif Afzal BCS 9 10 Muhammad Shabib BCS 10 11 Bilal Khan BCS 11 12 Ahmed Bin Shahid BCS 12 13 Waqar Ahmed Khan BCS 13 14 Sumaira Shafi BCS 14 15 Syed Sadik Aale Mohammed BCS 15 16 Muddassar Jameel Khan BCS 16 17 Rehan Haider Jaffery BCS 17 18 Mudassar Iqbal BCS 18 19 Tauqeer Abbas Dar BCS 19 20 Sana Haider BCS 20 21 Yasir Iqbal BCS 21 24 Saadia Amin Malik BCS 22 25 Tariq Khan BCS 23 26 Junaid Ikram BCS 24 28 Muhammad Naveed Zafar BCS 25 30 Cyra Ejaz BCS 26 33 Muhammad Rizwan Arif BCS 27 34 Ayesha Ashraf BCS 28 35 Muhammad Shoaib BCS 29 36 Hassan Tayyeb Tirmizi BCS 30 37 Tayyab Zeeshan BCS 31 38 Anjum Shahzad BCS 32 39 Saher Ahmed BCS 33 40 Muhammad Faisal Inam BCS 34 42 Muhammed Waqas Ali Saif BCS 35 43 Haroon Sheikh BCS 36 45 Amir Tufail BCS 37 46 Nauman Qamar BCS 38 47 Talha Rafiq BCS 39 10003 Zainab Shabbir BCS 40 10004 Ayesha Moin BCS 41 10005 Kamran Qamar Kiani BCS 42 10006 Amer Ali Khan BCS 43 10007 Saher Bashir BCS 44 10008 Umer Masood BCS 45 10009 Sidra Akhtar BCS 46 10011 Sohail Zafar BCS 47 10013 Muhammad Zeeshanul Haq BCS 48 10014 Rizwan - Ur - Rehman BCS 49 10015 Tooba Chaman BCS 50 10017 Urba Kiani BCS 51 10019 Abdur Rehman BCS 52 10020 Asad Kamal BCS 53 10022 Fouzia Aziz BCS 54 10023 Fahad Mehmood BCS 55 10024 Sadaqat Irfan BCS 56 10026 Nauman -

ICC Annual Report 2003-04 3 2003-04 Annual Report

2003-2004 Annual Report & Accounts Mission Statement ‘As the international governing body for cricket, the International Cricket Council will lead by promoting the game as a global sport, protecting the spirit of cricket and optimising commercial opportunities for the benefit of the game.’ ICC Annual Report 2003-04 3 2003-04 Annual Report & Accounts Contents 2 President’s Report 32 Integrity, Ethical Standards and Ehsan Mani Anti-Corruption 6 Chief Executive’s Review Malcolm Speed 36 Cricket Operations 9 Governance and 41 Development Organisational Effectiveness 47 Communication and Stakeholders 17 International Cricket 18 ICC Test Championship 51 Business of Cricket 20 ICC ODI Championship 57 Directors’ Report and Consolidated 22 ICC U/19 Cricket World Cup Financial Statements Bangladesh 2004 26 ICC Six Nations Challenge UAE 2004 28 Cricket Milestones 35 28 21 23 42 ICC Annual Report 2003-04 1 President’s Report Ehsan Mani My association with the ICC began in 1989 Cricket is an international game with a Cricket Development and over the last 15 years, I have seen the multi-national character. The Board of the ICC The sport’s horizons continue to expand with organisation evolve from being a small, is comprised of the Chairmen and Presidents China expected to be one of the countries under-resourced and reactive body to one of our Full Member countries as well as applying to take our total membership above that is properly resourced with a full-time representatives of our Associate Members. 90 countries in June. professional administration that leads the This allows for the views of all Members to We are conscious that the expansion of game in an authoritative manner for the be considered in the decision-making process. -

23TOIDC COL 01R3.QXD (Page 1)

OID‰‰†‰KOID‰‰†‰OID‰‰†‰MOID‰‰†‰C New Delhi, Saturday,August 23, 2003www.timesofindia.com Capital 38 pages* Invitation Price Rs. 1.50 International India Sport Vanessa juggles All for son: Kajol Sampras finally acting, singing prays for a boy decides to and parenting at Ajmer dargah call it a day Page 12 Page 8 Page 20 WIN WITH THE TIMES Condoms a Established 1838 dirty word Bennett, Coleman & Co., Ltd. Govt refuses to guard your CASh Believe those who are By N Vidyasagar seeking the truth. Doubt repeatedly been talking to at Centre, TIMES NEWS NETWORK those who find it. broadcasters about cable pric- ing, it has failed to make the lat- June 6 Free-to-air, okay. Free-for-all in the rest New Delhi: CAS is round the — Andre Gide ter reduce prices. Delhi waits corner, but the government says ‘‘We will work Q: Post CAS, what will be my until CAS reaches your locality. The government’s view comes By Nistula Hebbar it won’t monitor prices on behalf monthly cable bill? Q: Who will regulate the NEWS DIGEST at a time when cable TV homes to make CAS TIMES NEWS NETWORK of the consumer. All cable homes will pay Rs 98 for monopoly of cable operators? in CAS zones of four metros people-friendly. New Delhi: Is abstinence New uplinking guidelines: The ‘‘The market will determine free-to-air channels. All the major The monopoly continues. The govt the prices of pay channels. Cable have no idea about what they Package will better than using protection? government on Friday decided to re- will pay for pay channels from bouquets will cost Rs 200, so the has promised to enable new play- TV services should operate like I&B minister That may be a debate for the vise and strengthen its guidelines for September 1, 2003. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing.