Towards High-Quality, Well- Understood, Auditable Data in Gauteng’S Primary Healthcare Facilities Data Quality Baseline Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sibanye WRTRP EIA Kloof

27°20'0"E 27°30'0"E 27°40'0"E 27°50'0"E Robert Broom Dr Plan 1 Krugersdorp R Sibanye WRTRP ie Battery R24 M36 ts Wilgerood Rd p r u i t Lancaster Luipaardsvlei EIA Northway Dam Regional Setting Ventersdorp Rd M13 Vreysrus Randfontein Rd 26°10'0"S Legend N14 Randfontein Corlett Ave (M67) 26°10'0"S Major Town Porges Pit Secondary Town R41 Other Town Finsbury Settlement Cooke ip Plant l Main Rd (R559) K Main Roads Kocksoord Mohlakeng National Roads Water CD Railway Line Source: R558 Cooke 1 River R559 Dam Venterspos Water Source: Koma St (M72) Cooke 2 & 3 Soweto Infrastructure Bekkersdal Infrastructure Point Powerlines Pipelines: Kloof Mining Right Mooirivierloop Bank Westonaria R554 Pipelines: Driefontein Mining Right Lenasia Pipelines: Cooke Mining Right R500 26°20'0"S Pipelines: Ezulwini Mining Right 26°20'0"S K10 Water R28 supply M10 CPP and Future Uranium Plant Station C4N Water Libanon Regional Tailings Storage Facility Oberholzer WBT Source: Carletonville Cooke 4 Peter R501 Hillshaven Wright TSF within Kloof Mining Right DRI 3 C4S Dam Dalmore TSF within Driefontein Mining Right East Jagfontein N12 Lawley TSF within Cooke Mining Right Driefontein Glenharvie DRI 5 Estate Kloof Mining Right Ennerdale R577 Driefontein Mining Right South Deep R557 CPP Hermina Cooke Mining Right Grasmere Ezulwini Mining Right Leeudrif L e Fochville e us p N1 RTSF ru it R551 Sustainability Service Positive Change Professionalism Future Focused Integrity 26°30'0"S pruit 26°30'0"S Projection: Transverse Mercator Ref #: sdp.GOL2376.201508.010 ops R553 Lo Datum: -

GCRO 2009 Quality of Life Survey Field

N 1 1 Modimolle Makhuduthamaga Thabazimbi Mookgopong GCRO 2009 QuaL iilmityp o opfo Life Survey Field Map Thabazimbi Greater Tubatse Greater Marble Hall / 1 Bela-Bela N Greater Tubatse Moses Kotane Siyabuswa 294 Dr JS Moroka Assen 104 Moretele Elias Motsoaledi Ramotshere Moiloa 18 North Eastern Region Motshikiri 249 Makgabetlwane 235 Beestekraal 112 Temba 306 Babelegi 106 Tswaing 313 Hammanskraal 180 Local Municipality of Madibeng Kwamhlanga 215 Thembisile Maboloko 231 Ga-Mokone 170 Winterveld 333 Moloto 247 Letlhabile 224 Klippan 206 Sybrandskraal 305 Boshoek 121 Rooiwal 283 13 Nokeng tsa Taemane Mabopane 232 Ga-Luka 169 Rashoop 277 Emakhazeni Hebron 184 Bethanie 116 Lerulaneng 223 0 Phokeng 265 8 Selonsrivier 290 Elandsrand 156 R Lammerkop 217 N 14 North Western Region De Wildt 142 Bon Accord 119 4 Akasia 100 Bynespoort 127 Wonderhoek 336 Sonop 297 Cullinan 137 Photsaneng 266 Onderstepoort 258 Marikana 239 Sonderwater 296 Ekangala 154 Mafikeng Rustenburg Pretoria North 270 Mamelodi 236 Jacksonstuin 193 Hartbeespoort 183 Pretoria 269 Kroondal 212 Rayton 279 Kromdraai 211 Kgetlengrivier Mooinooi 248 Mhluzi 241 Kosmos 209 N4 1 Tshwane Middelburg (MP) 242 Garsfontein 172 Pelindaba 263 Bronkhorstspruit 126 4 Skeerpoort 295 Erasmia 163 Valhalla 315 N Centurion 130 Die Moot 146 Tierpoort 309 Balmoral 107 Steve Tshwete Doornrandjies 148 Irene 192 KwaGuqa 214 Witbank 334 Hekpoort 186 14 N 12 Kungwini Clewer 133 N o rr tt h W e s tt Maanhaarrand 230 Pinedene 267 4 West Rand Randjiesfontein 275 Welbekend 328 Elberta 158 1 Boons 120 Midrand 243 -

Vote 7: Housing

VOTE 7: HOUSING 1. Summary of Capital Budget for 2003/4 –2005/6 DESCRIPTION 2003/4 2004/05 2005/06 VOTED MTEF MTEF New capital projects 983,409 1,227,959 1,328,891 Maintenance 61,483 61,764 62,058 Other - Machinery and Equipment 3,618 3,799 3,033 Total 1,048,510 1,293,522 1,393,982 2. Description and Number of Capital Projects Annexure A (Vote 7) listed the major deliverables of the CAPEX programme. ANNEXURE A PROGRAMME 3: HOUSING FUND NEW CAPITAL Pro Program Region/D Municipal Project Project Medium Term Expenditure Framework Project Cost gra me istrict ity Number Descripti m Name on Cost No. (excl. personne l) Start Finish Budget 2003/04 2004/05 2005/06 Economic Classification Economic Classification Economic Classification SEDIBE NG METROP OLITAN COUNCI L MAYIBU Transfer Transfer Other Total Transfer Other Total Transfer Other Total YE R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 R'000 11 Lekoa- Southern Sedibeng G981203 Tshepiso 1918500 >03/04 05/06 Vaal 80 North 124 852 125 125 55 242 55 55 26 658 27 27 11 Lesedi Southern Sedibeng G981204 Heidelber 1040000 >03/04 05/06 06 g Ext. 23 Phase 2 180 310 180 180 79 783 80 80 42 361 42 42 11 Lekoa- Southern Sedibeng G981204 Sicelo 1893400 >03/04 05/06 Vaal 45 Shiceka (R 1 893 400) - Vaal 371 827 372 372 164 525 165 165 87 356 87 87 11 Lekoa- Southern Sedibeng G000100 Sonderw 945000 >03/04 05/06 Vaal 01 ater (R 1 004 500) - Vaal 359 117 359 359 158 901 159 159 84 370 84 84 0 0 RURAL HOUSIN 0 0 G 12 Lekoa- Southern Sedibeng Rietkuil 4250000 >03/04 05/06 Vaal 0 2 103 612 2 104 2 104 930 802 931 931 494 214 494 494 0 0 ESSENTI AL SERVIC ES 0 0 13 Lesedi Southern Sedibeng G941201 Ratanda 5630000 05/06 96/4 >02/03 1 590 931 1 591 1 591 703 952 704 704 373 767 374 374 13 Lesedi Southern Sedibeng G981204 Heidelber 1771000 >02/03 05/06 05/1 g Ext. -

Vegetation Units Prince Edward Islands

24° 25° 26° 27° 28° 29° 30° 31° 32° 33° 37°54'0"E 37°57'0"E 38°0'0"E PONTDRIF AZa7 AZa7 SVmp1 SVmp2 VAALKOP 22° BEIT BRIDGE Prince Edward Island MAPUNGUBWE SVmp2 NATIONAL PARK 46°36'0"S 46°36'0"S MOEDER-EN-KIND SVmp2 SVmp2 PO MUSINA LIMPO SVmp2 Prince Edward SVmp1 SVmp2 EPSILON VAN ZINDEREN SVmp2 KOP BAKKER PEAK BOGGEL FOa1 SVmp4 WOLKBERG SVmp1 SVmp1 SVmp1 PAFURI KENT CRATER e Islands l l e SVmp1 RSA Point zhe SVl1 N AZa7 FOz9 Cave Bay SVmp2 BROMBEEK FOz9 0 5 10 km AZa7 SVmp2 HOEDBERG TSHIPISE SVcb19 SVl1 SVmp3 SVl1 McNish Bay ALLDAYS 46°39'0"S Scale 1:150 000 46°39'0"S Biome Units of SVcb22 Luvuvhu MAASSTROOM SVmp2 SVmp1 le South Cape uta M FOz8 FOz9 SVmp4 South Africa, AZa7 SVcb19 SVcb21 SVl2 RADITSHABA Nzhelele SVcb21 FOa1 ´ 37°54'0"E 37°57'0"E 38°0'0"E SVmp1 Dam PUNDA MARIA SWARTWATER SVl1 Lesotho and Swaziland SVmp3 SVcb19 SVl1 37°36'0"E 37°39'0"E 37°42'0"E 37°45'0"E 37°48'0"E 37°51'0"E 37°54'0"E FOa1 SVcb20 SVcb21 SVl15 AZa7 WATERPOORT Mph TOLWE AZi11 o ngo Gm28 lo SVcb21 THOHOYANDOU SVl3 Cape Davis SVcb19 Gm28 FOz4 SVcb21 SVcb19 SVmp5 Gm28 SVmp5 FOz4 Storm Petrel Bay TOM BURKE SVcb18 FOz4 Marion Island VIVO KRUGER NATIONAL PARK MAKHADO FOz4 King Penguin Bay MARNITZ FOz4 BLOUBERG REPETTO'S HILL O Albasini Dam SVmp4 P O SVcb20 SHINGWEDZI P SVl8 46°51'0"S Glen Alpine Dam t SVl3 M d ELIM I GA-SELEKA SVl1 u Ship's Cove LONG RIDGE 46°51'0"S L SVcb18 n SVmp6 o a SVl7 SVcb19 H Sh S ing wed Trigaardt Bay BALTIMORE zi AZa7 BOCHUM AZORELLA KOP SKUA RIDGE 23° SVl3 Mixed Pickle Cove SVcb21 SVcb20 Hudson Ntsanwisi SVl8 Middle Letaba Dam Dam -

Biodiversity Impact Assessment

March 2020 19121900-328397-9 APPENDIX H Biodiversity Impact Assessment REPORT Specialist Assessment for the Proposed Surface Pipeline and Associated Infrastructure - Biodiversity Impact Assessment AngloGold Ashanti (Pty) Limited South African Operations Submitted to: Anglo Gold Ashanti (Pty) Limited South African Operations Mr J van Wyk Carletonville - Fochville Road R500 Carletonville Gauteng 2501 Submitted by: Golder Associates Africa (Pty) Ltd. Building 1, Maxwell Office Park, Magwa Crescent West, Waterfall City, Midrand, 1685, South Africa P.O. Box 6001, Halfway House, 1685 +27 11 254 4800 19121900-327695-6 February 2020 February 2020 19121900-327695-6 Distribution List 1 eCopy to Anglo Gold Ashanti (Pty) Limited South African Operations 1 eCopy to [email protected] i February 2020 19121900-327695-6 Executive Summary Project overview The AGA operations in the West Wits mining lease areas are at risk of flooding due to ingress of fissure water from surrounding mining operations. Approximately 25 Mℓ/day of fissure water flows into the underground workings of the defunct Blyvooruitzicht Mine, which spans a strike of 6 km along the boundary with AGA. If dewatering at the Old Blyvooruitzicht Shafts (#4, #5 & 6#) shafts were to cease, uncontrolled fissure water would report to the AGA operations, which would pose both a flood and safety risk of AGA personnel and the mining operations. This report provides a professional opinion regarding the anticipated terrestrial, wetland and aquatic impacts from this proposed project. Location The proposed water pipeline and associated infrastructure is located approximately 80 km west of Johannesburg. It originates at CWC 4#, approximately 3.3 km south east of Carletonville and ends at the North Boundary Dam (NBD) approximately 6 km south-south-west of Carletonville in Blyvooruitzicht, Merafong City Local Municipality, West Rand District Municipality in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. -

Department of Water and Sanitation SAFPUB V02 Output 19/09/2021 Latitude Longitude Drainage Catchment Page 1 Station Dd:Mm:Ss Dd:Mm:Ss Region Area Km**2 Description

Department of Water and Sanitation SAFPUB V02 Output 19/09/2021 Latitude Longitude Drainage Catchment Page 1 Station dd:mm:ss dd:mm:ss Region Area km**2 Description C1H001 Vaal River @ Langverwyl 26:56:33 29:15:50 C11M 8193 Data Data Period 100.00 Level (Metres) 1905-02-01 1989-02-21 3% missing 108.00 Downst Level(Metres) 1959-04-28 1989-01-24 Components Component Period C1H014 Vaal River @ Langverwyl 1905-02-01 C1H002 Klip River @ Sterkfontein 27:10:11 29:13:60 C13F 4152 Data Data Period 100.00 Level (Metres) 1906-10-01 2021-08-04 Components Component Period C1H016 Klip River @ Concrete Bridge Sterkfontein 1906-10-01 C1H015 Klip River @ Steel Bridge Sterkfontein 1963-10-29 C1H003 Vaal River @ Villiers 27:00:39 28:37:33 C12H 18616 Data Data Period 100.00 Level (Metres) 1938-08-06 1971-09-13 38% missing 108.00 Downst Level(Metres) 1966-06-22 1983-05-03 Components Component Period C1H017 Vaal River @ Villiers 1950-10-01 1956-08-24 C1H004 Waterval River @ Branddrift 26:37:41 29:01:28 C12D 901 Data Data Period 100.00 Level (Metres) 1960-08-12 2021-08-03 108.00 Downst Level(Metres) 1963-07-11 2018-03-27 C1H005 Leeu Spruit @ Welbedacht 26:51:15 29:19:31 C11L 336 Data Data Period 100.00 Level (Metres) 1964-12-04 2021-08-26 108.00 Downst Level(Metres) 1964-11-23 2021-08-26 230.70 Level (m) 2014-04-23 2016-01-20 21% missing 2351.50 Oxygen Concentration Realtime Ubuntu 2014-07-22 2016-01-20 13% missing 2351.70 Oxygen Concentration 2013-03-05 2016-01-20 10% missing 815.70 Temp (Deg C) Raw logger data 2013-03-05 2016-01-20 1% missing 820.50 Conductivity (MS/M) Realtime - Ubuntu 2014-07-22 2016-01-20 13% missing 822.70 Conduct. -

Recueil Des Colis Postaux En Ligne SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE

Recueil des colis postaux en ligne ZA - South Africa SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE LIMITED ZAA Service de base RESDES Informations sur la réception des Oui V 1.1 dépêches (réponse à un message 1 Limite de poids maximale PREDES) (poste de destination) 1.1 Colis de surface (kg) 30 5.1.5 Prêt à commencer à transmettre des Oui données aux partenaires qui le veulent 1.2 Colis-avion (kg) 30 5.1.6 Autres données transmis 2 Dimensions maximales admises PRECON Préavis d'expédition d'un envoi Oui 2.1 Colis de surface international (poste d'origine) 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non RESCON Réponse à un message PRECON Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus (poste de destination) grand pourtour) CARDIT Documents de transport international Oui 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non pour le transporteur (poste d'origine) (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus RESDIT Réponse à un message CARDIT (poste Oui grand pourtour) de destination) 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui 6 Distribution à domicile (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus grand pourtour) 6.1 Première tentative de distribution Oui 2.2 Colis-avion effectuée à l'adresse physique du destinataire 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non 6.2 En cas d'échec, un avis de passage est Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus laissé au destinataire grand pourtour) 6.3 Destinataire peut payer les taxes ou Non 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non droits dus et prendre physiquement (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus livraison de l'envoi grand pourtour) 6.4 Il y a des restrictions gouvernementales 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui ou légales vous limitent dans la (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus prestation du service de livraison à grand pourtour) domicile. -

Randfontein Main Seat of Randfontein Magisterial District

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C# # # ## # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ### # !C # # !C # # # # !C # # ## ## !C # # !C !. # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # ^ # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C## # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # ^ # ## !C # # # !C #!C ## # # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # -

ALL PUBLIC CERTIFIED ADULT LEARNING CENTRES in GAUTENG Page 1 of 8

DISTRICTS ABET CENTRE CENTRE TEL/ CELL PHYSICAL MUNICIPAL MANAGER ADDRESSES BOUNDARY Gauteng North - D1 / GN Taamane PALC Mr. Dladla D.A. (013) 935 3341 Cnr Buffalo & Gen Louis Bapsfontein, 5th Floor York Cnr. Park Van Jaan, Hlabelela, Zivuseni, 073 342 9798 Botha Baviaanspoort, Building Mandlomsobo, Vezu;wazi, [email protected] Bronkhorstspruit, 8b water Meyer street Mphumelomuhle, Rethabiseng, Clayville, Cullinan, Val de Grace Sizanani, Vezulwazi, Enkangala, GPG Building Madibatlou, Wozanibone, Hammanskraal, Pretoria Kungwini, Zonderwater Prison, Premier Mine, Tel: (012) 324 2071 Baviaanspoort Prison A & B. Rayton, Zonderwater, Mahlenga, Verena. Bekkersdal PALC Mr. Mahlatse Tsatsi Telefax: (011) 414-1952 3506 Mokate Street Gauteng West - D2 / GW Simunye, Venterspost, 082 878 8141 Mohlakeng Van Der Bank, Cnr Human & Boshoff Str. Bekkersdal; Westonaria, [email protected] Randfontein Bekkersdal, Krugersdorp 1740 Zuurbekom, Modderfontein, Brandvlei, Tel: (011) 953 Glenharvie, Mohlakeng, Doringfontein, 1313/1660/4581 Lukhanyo Glenharvie, Mosupatsela High Hekpoort, Kagiso PALC Mr. Motsomi J. M. (011) 410-1031 School Krugersdorp, Azaadville, Azaadville Sub, Fax(011) 410-9258 9080 Sebenzisa Drive Libanon, Khaselihle, Maloney’s Eye, 082 552 6304 Kagiso 2 Maanhaarrand, Silverfields, Sizwile, Sizwile 073 133 4391 Magaliesberg, Sub, Tsholetsega, [email protected] Mohlakeng, Tsholetsega Sub, Khaselihle Muldersdrift, Sub, Silverfieds Sub, Oberholzer, Munsieville. Randfontein, Randfontein South,The Village, Toekomsrus, Khutsong/ Motebong PALC Mr. S. F. Moleko fax:018 7830001 Venterspos, Mohlakeng, Badirile, 082 553 9580 3967 Nxumalo Road Western Areas, ALL PUBLIC CERTIFIED ADULT LEARNING CENTRES IN GAUTENG Page 1 of 8 Toekomsrus, Zenzele. Wedela, Telefax: (018) 788-5180 Khutsong Westonaria, 076 709 0469 Azaadville, Lebanon [email protected] Wedela/ Fochville PALC MS. A.Senoamadi Wedela, Sediegile Fax: (018) 780 1397 363 Ben Shibure 078 6155390 Avenue Kokosi Fochville Tshwane North - D3 / TN Gaerobe PALC Mr. -

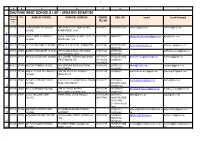

Gauteng West Schools List

1 A B C D F H I J 1 GAUTENG WEST SCHOOLS LIST - UPDATED 2016/01/20 Paypoint/ Emis NAME OF SCHOOL PHYSICAL ADDRESS SCHOOL CELL NO email Email Principal compone nt nr TEL NO 2 902009 270595 AB PHOKOMPE SECONDARY 7440 SEME STREET, MOHLAKENG, 0114140002 0825536025 GDE [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL RANDFONTEIN, 1759 3 902010 250027 AHMED TIMOL SECONDARY CNR OF KOHINOOR & KISMET STREET, 0114131323 0845815813 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL AZAADVILLE, 1750 4 902011 251199 ATLHOLANG PRIMARY SCHOOL 9079 SEBENZISA DRIVE, KAGISO 1754 0114101963 0825572384 GDE [email protected] [email protected] 6 0849412066 902012 270603 BADIRILE SECONDARY SCHOOL 3759 NXUMALO ROAD, KHUTSONG, 0187831564 0825558846 [email protected] 8 CARLETONVILLE 2499 0825532065 902013 251231 BOIPELO SECONDARY SCHOOL 4113 CORNER THEMBA & MOGOROSI 0114101001 0825558050 GDE [email protected] [email protected] DRIVE, KAGISO 1754 0114102916 0825555080 10 0114108066 902001 271478 BOITEKO PRIMARY SCHOOL 5840 SOMPANE ROAD, KHUTSONG, 0187833350 0825572339 [email protected] [email protected] 11 WESTONARIA 0832406970 902015 251264 BOSELE PUBLIC INTERMEDIATE 1676 THEMBA DRIVE, KAGISO 2, 0114101269 0825564401 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL MOGALE CITY 12 902016 270645 BRANDVLEI PRIMARY FARM PLOT 55 VENTERSDORP/RUSTENBURG 0114162122 0827216894 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL ROAD, RANDFONTEIN 0825542389 GDE 13 0731959492b 902017 270652 BULELANI PRIMARY SCHOOL 2189 RALERATA STREET, 0114141190 071 347 6165 [email protected] [email protected] 14 MOHLAKENG, RANDFONTEIN 0114141140 0824837932 902018 270041 CARLETON JONES HIGH ANNAN ROAD, CARLETONVILLE 0187883239/0 0825533315 [email protected] [email protected] SCHOOL 0845157440 0828517969 GDE 082 8517970 (0713647516 Dept 16 Dries) 902019 251306 DIE POORT PRIMARY FARM RUSTENBURG AND BRITS ROAD, 0710557514 [email protected]. -

Building Statistics, 2017

Building statistics, 2017 Embargoed until: 28 August 2019 14:30 Statistics South Africa Risenga Maluleke Report No. 50-11-01 (2017) Statistician-General STATISTICS SOUTH AFRICA i Building statistics, 2017 / Statistics South Africa Published by Statistics South Africa, Private Bag X44, Pretoria 0001 © Statistics South Africa, 2019 Users may apply or process this data, provided Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) is acknowledged as the original source of the data; that it is specified that the application and/or analysis is the result of the user's independent processing of the data; and that neither the basic data nor any reprocessed version or application thereof may be sold or offered for sale in any form whatsoever without prior permission from Stats SA. Stats SA Library Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) Data Building statistics, 2017 / Statistics South Africa. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa, 2019 Report No. 50-11-01 (2017) 52 pp ISBN 978-0-621-47787-0 A complete set of Stats SA publications is available at Stats SA Library and the following libraries: National Library of South Africa, Pretoria Division Eastern Cape Library Services, King William's Town National Library of South Africa, Cape Town Division Central Regional Library, Polokwane Library of Parliament, Cape Town Central Reference Library, Mbombela Bloemfontein Public Library Central Reference Collection, Kimberley Natal Society Library, Pietermaritzburg Central Reference Library, Mmabatho Johannesburg Public Library This report is available on the Stats SA website: www.statssa.gov.za For technical enquiries, please contact: Tsholofelo Ditinti / Nicolai Claassen Tel.: 012 310 6990 / 012 310 8007 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Building statistics, Report No. -

Oberholzer Main Seat of Merafong City Magisterial District

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # !C # # !C # #^ # # # # # # # ## # # #!C # # # # # # !C # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # ##^ !C # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # #!C # !C# # # ##!C # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # !C # # #!C # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ### # # !C # !C # # !C # ## ## # ## !C # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # !C !C## # # # ## # !C # # # # # !C# # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # ^ # # # !C# ^ # # ## !C # # # !C #!C ## # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # #