1 Classic Comix Classix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RACHAEL SMITH, BENJAMIN DICKSON Queen's Favorite Witch #1

PAPERCUTZ • OCTOBER 2021 JUVENILE FICTION / COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS / FANTASY RACHAEL SMITH, BENJAMIN DICKSON Queen's Favorite Witch #1 Meet Daisy, a precocious, down on her luck witch who is thrust into the world of royal intrigue when she applies to become The Queen's Favorite Witch! Elizabethan England is a time of superstition and strange goings on. If you have a problem, it’s common to go to a witch for help. And Queen Elizabeth I is no different… When Daisy -- a precocious young witch -- learns of the death of the Queen's Royal Witch, she flies to London to audition as her replacement. But Daisy is from a poor family, and they don't let just anyone into the Royal Court. The only OCTOBER Papercutz way into the palace is to take a job as a cleaner. Juvenile Fiction / Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy As Daisy cleans the palace, she draws the attention of On Sale 10/19/2021 Elizabeth's doctor (and arch-heretic) John Dee, who places Ages 7 to 12 her into the auditions -- much to the chagrin of her more Trade Paperback , 112 pages well-to-do competitors. But Dee knows how dangerous the 9 in H | 6 in W Carton Quantity: 60 corridors of power have become, with dark forces ISBN: 9781545807224 manipulating events for their own ends. To him, Daisy $9.99 / $12.99 Can. represents a wild card -- ... Benjamin Dickson is a writer, artist and lecturer who most recently produced the critically-acclaimed A New Jerusalem for New Internationalist/Myriad Editions (also published in France as Le Retour, by Actes Sud). -

Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers Into the Library

School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts Department of Information Studies Graphic Novels: Enticing Teenagers into the Library Clare Snowball This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University of Technology March 2011 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: _____________________________ Date: _________________________________ Page i Abstract This thesis investigates the inclusion of graphic novels in library collections and whether the format encourages teenagers to use libraries and read in their free time. Graphic novels are bound paperback or hardcover works in comic-book form and cover the full range of fiction genres, manga (Japanese comics), and also nonfiction. Teenagers are believed to read less in their free time than their younger counterparts. The importance of recreational reading necessitates methods to encourage teenagers to enjoy reading and undertake the pastime. Graphic novels have been discussed as a popular format among teenagers. As with reading, library use among teenagers declines as they age from childhood. The combination of graphic novel collections in school and public libraries may be a solution to both these dilemmas. Teenagers’ views were explored through focus groups to determine their attitudes toward reading, libraries and their use of libraries; their opinions on reading for school, including reading for English classes and gathering information for school assignments; and their liking for different reading materials, including graphic novels. -

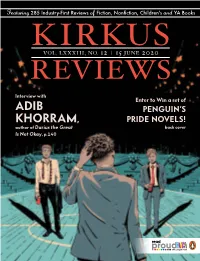

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― the Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated

Submitted October 3, 2011 Published January 27, 2012 Proposé le 3 octobre 2011 Publié le 27 janvier 2012 From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― The Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated William B. Jones, Jr. Abstract From 1941 to 1971, the Classics Illustrated series of comic-book adaptations of works by Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, and others provided a gateway to great literature for millions of young readers. Jules Verne was the most popular author in the Classics catalog, with ten titles in circulation. The first of these to be adapted, Michael Strogoff (June 1946), was the favorite of the Russian-born series founder, Albert L. Kanter. The last to be included, Tigers and Traitors (May 1962), indicated how far among the Extraordinary Voyages the editorial selections could range. This article explores the Classics Illustrated pictorial abridgments of such well-known novels as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in 80 Days and more esoteric selections such as Off on a Comet and Robur the Conqueror. Attention is given to both the adaptations and the artwork, generously represented, that first drew many readers to Jules Verne. Click on images to view in full size. Résumé De 1941 à 1971, la collection de bandes dessinées des Classics Illustrated (Classiques illustrés) offrant des adaptations d'œuvres de Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, et d'autres a fourni une passerelle vers la grande littérature pour des millions de jeunes lecteurs. Jules Verne a été l'auteur le plus populaire du catalogue des Classics, avec dix titres en circulation. -

Visualizing the Romance: Uses of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Narratives in Comics1

Visualizing the Romance: Uses of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Narratives in Comics1 Derek Parker Royal Classic works of American literature have been adapted to comics since the medium, especially as delivered in periodical form (i.e., the comic book), first gained a pop cultural foothold. One of the first texts adapted by Classic Comics, which would later become Classics Illustrated,2 was James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, which appeared in issue #4, published in August 1942. This was immediately followed the next month by a rendering of Moby-Dick and then seven issues later by adaptations of two stories by Washington Irving, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Headless Horseman.”3 As M. Thomas Inge points out, Edgar Allan Poe was one of the first, and most frequent, American authors to be translated into comics form (Incredible Mr. Poe 14), having his stories adapted not only in early issues of Classic Comics, but also in Yellow- jacket Comics (1944–1945) and Will Eisner’s The Spirit (1948).4 What is notable here is that almost all of the earliest adaptations of American literature sprang not only from antebellum texts, but from what we now consider classic examples of literary romance,5 those narrative spaces between the real and the fantastic where psychological states become the scaffolding of national and historical morality. It is only appropriate that comics, a hybrid medium where image and text often breed an ambiguous yet pliable synthesis, have become such a fertile means of retelling these early American romances. Given this predominance of early nineteenth-century writers adapted to the graphic narrative form, it is curious how one such author has been underrepresented within the medium, at least when compared to the treatment given to his contemporaries. -

Spring/Summer 2014 Hotlist Juvenile and Teen

SPRING/SUMMER 2014 HOTLIST JUVENILE AND TEEN Orders due by May 9, 2014 Skylight Books is the wholesale division of McNally Robinson Booksellers. We offer Hotlist service to libraries in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Our discounts are competitive and our hotlists are selected specifically to serve prairie readers by including, along with national and international bestsellers, regional titles and books from regional authors and publishers. The Hotlist is now available on the institutional page of mcnallyrobinson.com. To access the institutional page of mcnallyrobinson.com, please contact [email protected] Skylight Books #2-90 Market Avenue Winnipeg, MB R3B 0P3 Phone: 204-339-2093 Fax: 204-339-2094 Email: wendy @ skylight.mcnallyrobinson.ca SKYLIGHT BOOKS SPRING/SUMMER 2014 HOTLIST The reviews are read, the catalogues marked, and the representatives appointments completed. All in preparation to bring you and your patrons our selections for the upcoming Spring/Summer seasons. So welcome to Skylight Books Spring/Summer Hotlist catalogues bursting with hot Spring/Summer releases from well-loved and in-demand authors and series yes. But also lesser gems from debut and upcoming international, national and regional voices. Best of all, and back by popular demand, our "Picks of the Season" as chosen by our dedicated publisher representatives. Please note, some rep selections may not appear in our Hotlist catalogues. For your ordering convenience we will post a "Reps Picks" spreadsheet on the Institutional page of our website. We thank the following representatives for sharing their picks for the Spring/Summer seasons: Rorie Bruce ± Publishers Group Canada Jean Cichon ± Hachette Book Group (Canadian Manda Group) Joedi Dunn ± Simon And Shuster Canada Mary Giuliano ± Random House Canada Judy Parker ± MacMillan Publishing Group, Raincoast Books, (Ampersand Inc. -

Nominees Announced for 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards Sonny Liew’S the Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Tops List with Six Nominations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jackie Estrada [email protected] Nominees Announced for 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Tops List with Six Nominations SAN DIEGO – Comic-Con International (Comic-Con) is proud to announce the nominations for the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards 2017. The nominees were chosen by a blue-ribbon panel of judges. Once again, this year’s nominees reflect the wide range of material being published in comics and graphic novel form today, with over 120 titles from some 50 publishers and by creators from all over the world. Topping the nominations is Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Pantheon), originally published in Singapore. It is a history of Singapore from the 1950s to the present as told by a fictional cartoonist in a wide variety of styles reflecting the various time periods. It is nominated in 6 categories: Best Graphic Album–New, Best U.S. Edition of International Material–Asia, Best Writer/Artist, Best Coloring, Best Lettering, and Best Publication Design. Boasting 4 nominations are Image’s Saga and Kill or Be Killed. Saga is up for Best Continuing Series, Best Writer (Brian K. Vaughan), and Best Cover Artist and Best Coloring (Fiona Staples). Kill or Be Killed by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips is nominated for Best Continuing Series, Best Writer, Best Cover Artist, and Best Coloring (Elizabeth Breitweiser). Two titles have 3 nominations: Image’s Monstress by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda (Best Publication for Teens, Best Painter, Best Cover Artist) and Tom Gauld’s Mooncop (Best Graphic Album–New, Best Writer/Artist, Best Lettering), published by Drawn & Quarterly. -

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films

Video 108 Media Corp 9 Story A&E Networks A24 All Channel Films Alliance Entertainment American Cinema Inspires American Public Television Ammo Content Astrolab Motion Bayview Entertainment BBC Bell Marker Bennett-Watt Entertainment BidSlate Bleecker Street Media Blue Fox Entertainment Blue Ridge Holdings Blue Socks Media BluEvo Bold and the Beautiful Brain Power Studio Breaking Glass BroadGreen Caracol CBC Cheng Cheng Films Christiano Film Group Cinedigm Cinedigm Canada Cinema Libre Studio CJ Entertainment Collective Eye Films Comedy Dynamics Content Media Corp Culver Digital Distribution DBM Films Deep C Digital DHX Media (Cookie Jar) Digital Media Rights Dino Lingo Disney Studios Distrib Films US Dreamscape Media Echelon Studios Eco Dox Education 2000 Electric Entertainment Engine 15 eOne Films Canada Epic Pictures Epoch Entertainment Equator Creative Media Everyday ASL Productions Fashion News World Inc Film Buff Film Chest Film Ideas Film Movement Film UA Group FilmRise Filmworks Entertainment First Run Features Fit for Life Freestyle Digital Media Gaiam Giant Interactive Global Genesis Group Global Media Globe Edutainment GoDigital Inc. Good Deed Entertainment GPC Films Grasshopper Films Gravitas Ventures Green Apple Green Planet Films Growing Minds Gunpowder & Sky Distribution HG Distribution Icarus Films IMUSTI INC Inception Media Group Indie Rights Indigenius Intelecom Janson Media Juice International KDMG Kew Media Group KimStim Kino Lorber Kinonation Koan Inc. Language Tree Legend Films Lego Leomark Studios Level 33 Entertainment -

MAURICIO DE SOUSA, ARTIST: ZAZO Monica Adventures #1 “What a Day!”

SUPER GENIUS • MARCH 2019 YOUNG ADULT FICTION / COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS / COMING OF AGE VITOR CAFAGGI Vincent Book One Guide to Love, Magic, and RPG "How I Met Your Mother" told with all the heart...and animals! It's been some time since Vincent has had a good day. Sitting on the bus, he still doesn't know that his life is about to change. Forever. At that moment, outside the bus, Lady lets a little smile escape when recalling an anecdote about tomatoes. Vincent sees the smile and his world turns upside down. Now, armed with his nerdy RPG friends(not counting Bu, who is like a sister to Vincent and full of solid wisdom), an impressive magic act, and a insatiable love of roast beef sandwiches (no pickles, Vincent hates pickles), he must learn MARCH how to navigate his first non-platonic love and what may Super Genius happen if things don't go as planned (as they often do in the Young Adult Fiction / Comics & Graphic Novels / Coming life of Vincent). Of Age On Sale 3/19/2019 Vitor Cafaggi is a professor of visual narrative, script and character Ages 14 And Up Trade Paperback , 96 pages development in Minas Gerais, Brazil. His debut to the world of 8 in H | 8 in W comics was with the webcomic Puny Parker, which narrated the Carton Quantity: 45 childhood of his favorite hero, Spider-Man. He gained notoriety in ISBN: 9781545805343 his country with the graphic novels inspired by Brazilian super- $9.99 / $12.99 Can. property Turma da Mônica (Monica and Friends) and the comic strip Valente (Vincent) published by the Brazilian newspaper O Globo. -

Free Comic Book Day 2017 Checklist

Free Comic Book Day May 6th, 2017 Comics Checklist DC SUPER HERO GIRLS (Shea Fontana, Yancy Labat, DC Comics) Gold Comics COLORFUL MONSTERS BETTY & VERONICA #1 (Anouk Ricard, Elise Gravel, Drawn & Quarterly) (Adam Hughes, Archie Comics) HOSTAGE BONGO COMICS FREE-FOR-ALL (Guy Delisle, Brigitte Findakly Drawn & Quarterly) (Matt Groening, Bongo Comics) ANIMAL JAM BOOM! STUDIOS SUMMER BLAST (Fernando Ruiz, Pete Pantazis, D.E.) (David Petersen, Kyla Vanderklugt, Boom! Studios) TEX PATAGONIA BRIGGS LAND/JAMES CAMERON’S AVATAR (Mauro Boselli, Pasquale Frisenda, D.E.) (Sherri Smith, Brian Wood, Doug Wheatley, Werther Dell’Edera, Dark WORLD’S GREATEST CARTOONISTS Horse Comics) (Noah Van Sciver, Fantagraphics) WONDER WOMAN SPILL NIGHT (Greg Rucka, Nicola Scott, DC Comics) (Scott Westerfeld, Alex Puvilland, :01 First Second) STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION: MIRROR BROKEN GRAPHIX SPOTLIGHT: TIME SHIFTERS (Scott Tipton, David Tipton, J. K. Woodward, IDW) (Chris Grine, Graphix) I HATE IMAGE THE INCAL (Skottie Young, Image Comics) (Alejandro Jodorowsky, Moebius, U-Jin, Humanoids Inc.) SECRET EMPIRE TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: PRELUDE TO (Nick Spencer, Andrea Sorrentino, Marvel Comics) DIMENSION X RICK & MORTY (Tom Waltz, Cory Smith, IDW) (Zac Gorman, Tini Howard, CJ Cannon, Maximus Pauson, Oni Press) KID SAVAGE DOCTOR WHO (Joe Kelly, Ilya, Image Comics) (Alex Paknadel, Mariano Laclaustra, Titan Comics) ATTACK ON TITAN X-O MANOWAR SPECIAL (Jody Houser, Emi Lenox, Paolo Rivera, Kodansha Comics) (Matt Kindt, Jeff Lemire (A) Tomas -

Why Graphic Novels?

Why Graphic Novels? Graphic novels may be a new format for your store, but they’re still all about telling stories. The way graphic novels tell their stories – with integrated words and pictures – looks different from traditional novels, poetry, plays, and picture books, but the stories they tell have the same hearts. Bone, by Jeff Smith, is a fantastical adventure with a monstrous villain and endearing heroes, like Harry Potter. American Born Chinese, by Gene Luen Yang, is a coming-of-age novel, like Catcher in the Rye. Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel, is a powerful memoir, like Running With Scissors. When people ask, ‘why graphic novels?’ the easiest answer you can give is, graphic novels tell stories that are just as scary and funny and powerful and heartwarming as prose. Here are two more sophisticated answers you can also try out. Education Graphic novels are a great way to go for kids making the transition from image-centric books to more text-based books, and for adults just learning English. Because of the combination of image and text in a graphic novel, readers get visual clues about what’s going on in the story even if their vocabulary isn’t quite up to all the words yet. And because graphic novels are told as a series of panels, reading graphic novels also forces readers to think and become actively involved each time they move between one panel and the next. What’s happening in that space? How do the story and the characters get from panel 1 to panel 2? Both television and the internet play a large part in our culture – images are becoming more and more integrated into everyone’s everyday life. -

S18-Papercutz.Pdf

SUPER GENIUS • MAY 2018 COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS / HORROR DAVID GALLAHER AND STEVE ELLIS High Moon Vol. 2: "Wicked Ways" The fate of humanity hangs by the skin of its teeth in the second volume of HIGH MOON. The award-winning werewolf western series continues in HIGH MOON: WICKED WAYS. After a horrific series of murders, Macgregor joins forces with a gang of outlaws to stop an army from unleashing untold devastation. But something sinister is brewing across the globe — and danger will bring the detective to London where he will find himself face-to-face with a gruesome plot that threatens the fabric of humanity. David Gallaher (BOX 13) and Steve Ellis (THE MAY ONLY LIVING BOY) re-unite for this legendary series which Super Genius features a 16 page never-seen-before bonus story! Comics & Graphic Novels / Horror On Sale5/1/2018 DAVID GALLAHER Ages 13 to 18 has received multiple Harvey Award Trade Paperback , 148 pages nominations and won The Best Online Comic Award for his work 11 in H | 8.5 in W on HIGH MOON. He has served as a consultant for Random Carton Quantity: 30 House, The NYPD, and McGraw-Hill. ISBN:9781545800010 $14.99 / $19.50 Can. STEVE ELLIS has created artwork and conceived projects for numerous companies. Recently he has developed the award Also available winning comic series HIGH MOON as well as acted as the lead designer, storyboard artist and illustrator on AMC's Breaking Bad: The Cost of Doing Business and The Walking Dead: Dead Reckoning games. High Moon Vol. 1: “Bullet Holes and Bite Marks” 9781629918419 $14.99/$20.99 Can.