Eosinophilic Granulomatous Gastrointestinal and Hepatic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pediatric Invasive Gastrointestinal Fungal Infections: Causative Agents and Diagnostic Modalities

Microbiology Research Journal International 19(2): 1-11, 2017; Article no.MRJI.32231 Previously known as British Microbiology Research Journal ISSN: 2231-0886, NLM ID: 101608140 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Pediatric Invasive Gastrointestinal Fungal Infections: Causative Agents and Diagnostic Modalities Mortada H. F. El-Shabrawi 1, Lamiaa A. Madkour 2* , Naglaa Kamal 1 and Kerstin Voigt 3 1Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt. 2Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt. 3Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, University of Jena, Germany. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author MHFES specified the topic of the research. Author LAM designed the study, managed the literature research and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors NK and KV wrote the subsequent drafts. Author MHFES revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/MRJI/2017/32231 Editor(s): (1) Raúl Rodríguez-Herrera, Autonomous University of Coahuila, México. Reviewers: (1) Hasibe Vural, Necmettin Erbakan Üniversity, Turkey. (2) Berdicevsky Israela, Technion Faculty of Medicine, Haifa, Israel. (3) Vassiliki Pitiriga, University of Athens, Greece. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/18327 Received 16 th February 2017 th Review Article Accepted 18 March 2017 Published 24 th March 2017 ABSTRACT Invasive gastrointestinal fungal infections are posing a serious threat to the ever-expanding population of immunocompromised children, as well as some healthy children at risk. In this narrative review, we collate and explore the etiologies and diagnostic modalities of these overlooked infections. -

Pulmonary Basidiobolomycosis: an Unusual Presentation in a Cancer Patient: a Case Report and Mini Review of Cases in India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2015) 4(5): 798-805 ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 4 Number 5 (2015) pp. 798-805 http://www.ijcmas.com Case Study Pulmonary Basidiobolomycosis: An unusual presentation in a cancer patient: A case report and mini review of cases in India Deba Dulal Biswal1, Manisa Sahu2* and Pallavi Bhaleker3 1Department of Medical Oncology, S L Raheja Hospital (A Fortis Associate) Mahim (W), Mumbai-400016, India 2Department of Microbiology, S L Raheja Hospital (A Fortis Associate) Mahim(W), Mumbai-400016, India *Corresponding author A B S T R A C T K e y w o r d s Basidiobolomycosis is an uncommon disease caused by Basidiobolus Basidiobolo- ranarum. The clinical presentation varies from localized subcutaneous mycosis, infection to widespread dissemination involving different viscera s, notably Basidio-bolus the gastrointestinal tract. Pulmonary involvement is rarer; we report a case ranarum, of pulmonary Basidiobolomycosis in a lung cancer patient. lung cancer Introduction Basidiobolo mycosis is caused by the fungus cases are from Southern part.( Sujatha S et Basidiobolus ranarum, which is a al., 2003; Chandrasekhar HR et al., 1998; zygomycetes belonging to order Prasad PV et al., 2002; Krishnan et al., Entomophthorales. (Gugnani, H. C et al., 1998) Rare dissemination with visceral 1999) This filamentous fungus is usually involvement by Basidiobolus are quoted by associated with subcutaneous zygomycosis various authors such as gastrointestinal tract, of trunk and limbs in immune competent uterus, urinary bladder and retro peritoneum. individuals (Ribes JA et al., 2000) It is an (Bigliazzi C et al., 2004; Khan ZU et al., environmental saprophyte isolated mostly 2001; Nazir Z et al., 1997; Choonhakarn C from decaying vegetation, foodstuffs, fruits, et al., 2004) Pulmonary involvement are and soil. -

Opportunistic Invasive Fungal Infections: Diagnosis & Clinical

Review Article Indian J Med Res 139, February 2014, pp 195-204 Opportunistic invasive fungal infections: diagnosis & clinical management Parisa Badiee & Zahra Hashemizadeh Prof. Alborzi Clinical Microbiology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran Received May 14, 2013 Invasive fungal infections are a significant health problem in immunocompromised patients. The clinical manifestations vary and can range from colonization in allergic bronchopulmonary disease to active infection in local aetiologic agents. Many factors influence the virulence and pathogenic capacity of the microorganisms, such as enzymes including extracellular phospholipases, lipases and proteinases, dimorphic growth in some Candida species, melanin production, mannitol secretion, superoxide dismutase, rapid growth and affinity to the blood stream, heat tolerance and toxin production. Infection is confirmed when histopathologic examinationwith special stains demonstrates fungal tissue involvement or when the aetiologic agent is isolated from sterile clinical specimens by culture. Both acquired and congenital immunodeficiency may be associated with increased susceptibility to systemic infections. Fungal infection is difficult to treat because antifungal therapy forCandida infections is still controversial and based on clinical grounds, and for molds, the clinician must assume that the species isolated from the culture medium is the pathogen. Timely initiation of antifungal treatment is a critical component affecting the outcome. Disseminated infection requires the use of systemic agents with or without surgical debridement, and in some cases immunotherapy is also advisable. Preclinical and clinical studies have shown an association between drug dose and treatment outcome. Drug dose monitoring is necessary to ensure that therapeutic levels are achieved for optimal clinical efficacy. The objectives of this review are to discuss opportunistic fungal infections, diagnostic methods and the management of these infections. -

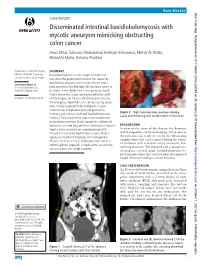

Disseminated Intestinal Basidiobolomycosis with Mycotic

Rare disease BMJ Case Rep: first published as 10.1136/bcr-2018-225054 on 29 January 2019. Downloaded from CASE REPORT Disseminated intestinal basidiobolomycosis with mycotic aneurysm mimicking obstructing colon cancer Arwa Omar Takrouni, Mohammad Heitham Schammut, Mishal Al-Otaibi, Manal Al-Mulla, Antonio Privitera Department of General Surgery, SUMMARY Ministry of Health, Dammam, Basidiobolomycosis is a rare fungal infection that Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia may affect the gastrointestinal tract. It is caused by Basidiobolus ranarum and less than 80 cases have Correspondence to Dr Arwa Omar Takrouni, been reported in the literature. The incidence seems to dr. arwa207@ gmail. com be higher in the Middle East and in particular Saudi Arabia where most cases are diagnosed in the south- Accepted 10 December 2018 western region. An 18-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with an obstructing caecal mass initially suspected to be malignant. Surgical resection was complicated by bowel perforation, Figure 2 Right hemicolectomy specimen showing histology and cultures confirmed basidiobolomycosis caecal wall thickening with necrotic debris in the lumen. infection. The postoperative course was complicated by an enterocutaneous fistula, fungal intra-abdominal abscesses, liver and lung abscesses, formation of mycotic BACKGROUND hepatic artery aneurysm and meningoencephalitis. In view of the rarity of the disease, the diagnosis The patient eventually expired due to sepsis despite and management can be challenging. The nature of aggressive treatment. Diagnosis and management the infection can result in several life-threatening complications that can be missed during the course of such rare cases are very challenging and require a of treatment such as hepatic artery aneurysm, liver multidisciplinary approach. -

Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-Diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: a Review Article

IJMS Vol 40, No 2, March 2015 Review Article Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: A Review Article Bita Geramizadeh1,2, MD; Mina Abstract 2 2 Heidari , MD; Golsa Shekarkhar , MD Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is an unusual, rare, but emerging fungal infection in the stomach, small intestine, colon, and liver. It has been rarely reported in the English literature and most of the reported cases have been from US, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iran. In the last five years, 17 cases have been reported from one or two provinces in Iran, and it seems that it has been undiagnosed or probably unnoticed in other parts of the country. This article has Continuous In this review, we explored the English literature from 1964 Medical Education (CME) through 2013 via PubMed, Google, and Google scholar using the credit for Iranian physicians following search keywords: and paramedics. They may 1) Basidiobolomycosis earn CME credit by reading 2) Basidiobolus ranarum this article and answering the 3) Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis questions on page 190. In this review, we attempted to collect all clinical, pathological, and radiological findings of the presenting patients; complemented with previous experiences regarding the treatment and prognosis of the GIB. Since 1964, only 71 cases have been reported, which will be fully described in terms of clinical presentations, methods of diagnosis and treatment as well as prognosis and follow up. Please cite this article as: Geramizadeh B, Heidari M, Shekarkhar G. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: A Review Article. Iran J Med Sci. -

Isolated Hepatic Basidiobolomycosis in a 2-Year-Old

Hepat Mon. 2015 August; 15(8): e30117. DOI: 10.5812/hepatmon.30117 Case Report Published online 2015 August 29. Isolated Hepatic Basidiobolomycosis in a 2-Year-Old Girl: The First Case Report 1,* 2 2 3 Bita Geramizadeh ; Anahita Sanai Dashti ; Mohammad Rahim Kadivar ; Shirin Kord 1Transplant Research Center, Pathology Department, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, IR Iran 2Dr. Alborzi Microbiology Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, IR Iran 3Department of Pathology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, IR Iran *Corresponding Author : Bita Geramizadeh, Transplant Research Center, Pathology Department, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, IR Iran. Tel: +98-9173143438, E-mail: [email protected] Received: ; Revised: ; Accepted: May 20, 2015 June 28, 2015 July 13, 2015 Introduction: Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis is an emerging infection, with fewer than 80 cases reported in the English literature. Case Presentation: Also, a few cases of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis, accompanied by liver involvement as part of a disseminated disease, have been reported. Conclusions: This is the first case report of an isolated liver involvement of this fungal infection in a 2-year-old girl, who presented with a liver mass resembling a hepatic abscess. Keywords: Liver; Basidiobolomycosis; Immunocompetent 1. Introduction Zygomycosis includes 2 orders, one of which causes fun- delivery without any specific disorder. She had had a nor- gal infections in an immunocompromised host (Mucora- mal infancy until 2 months prior to her referral, when les) and the other in an immunocompetent host (Ento- she developed abdominal pain with no response to rou- mophthorales) (1). tine treatment. Basidiobolus ranarum belongs to the second group and Physical examination was normal, except for mild hepa- is a saprophyte found mostly in soil and decaying vege- tomegaly. -

Fungal Infections

FUNGAL INFECTIONS SUPERFICIAL MYCOSES DEEP MYCOSES MIXED MYCOSES • Subcutaneous mycoses : important infections • Mycologists and clinicians • Common tropical subcutaneous mycoses • Signs, symptoms, diagnostic methods, therapy • Identify the causative agent • Adequate treatment Clinical classification of Mycoses CUTANEOUS SUBCUTANEOUS OPPORTUNISTIC SYSTEMIC Superficial Chromoblastomycosis Aspergillosis Aspergillosis mycoses Sporotrichosis Candidosis Blastomycosis Tinea Mycetoma Cryptococcosis Candidosis Piedra (eumycotic) Geotrichosis Coccidioidomycosis Candidosis Phaeohyphomycosis Dermatophytosis Zygomycosis Histoplasmosis Fusariosis Cryptococcosis Trichosporonosis Geotrichosis Paracoccidioidomyc osis Zygomycosis Fusariosis Trichosporonosis Sporotrichosis • Deep / subcutaneous mycosis • Sporothrix schenckii • Saprophytic , I.P. : 8-30 days • Geographical distribution Clinical varieties (Sporotrichosis) Cutaneous • Lymphangitic or Pulmonary lymphocutaneous Renal Systemic • Fixed or endemic Bone • Mycetoma like Joint • Cellulitic Meninges Lymphangitic form (Sporotrichosis) • Commonest • Exposed sites • Dermal nodule pustule ulcer sporotrichotic chancre) (Sporotrichosis) (Sporotrichosis) • Draining lymphatic inflamed & swollen • Multiple nodules along lymphatics • New nodules - every few (Sporotrichosis) days • Thin purulent discharge • Chronic - regional lymph nodes swollen - break down • Primary lesion may heal spontaneously • General health - may not be affected (Sporotrichosis) (Sporotrichosis) Fixed/Endemic variety (Sporotrichosis) • -

Basidiobolus Omanensis Sp. Nov. Causing Angioinvasive Abdominal Basidiobolomycosis

Journal of Fungi Article Basidiobolus omanensis sp. nov. Causing Angioinvasive Abdominal Basidiobolomycosis Abdullah M. S. Al-Hatmi 1,2,3,* , Abdullah Balkhair 4, Ibrahim Al-Busaidi 4 , Marcelo Sandoval-Denis 5, Saif Al-Housni 1, Hashim Ba Taher 4, Asmaa Hamdan Al Shehhi 6, Sameer Raniga 7 , Maha Al Shaibi 8, Turkiya Al Siyabi 9, Jacques F. Meis 3,10 , G. Sybren de Hoog 3 , Ahmed Al-Rawahi 1, Zakariya Al Muharrmi 9, Ahmed Al-Harrasi 1 and Badriya Al Adawi 9,* 1 Natural & Medical Sciences Research Center, University of Nizwa, Nizwa 616, Oman; [email protected] (S.A.-H.); [email protected] (A.A.-R.); [email protected] (A.A.-H.) 2 Department of Biological Sciences & Chemistry, College of Arts and Sciences, University of Nizwa, Nizwa 616, Oman 3 Centre of Expertise in Mycology, Radboud University Medical Centre/Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, 6532 SZ Nijmegen, The Netherlands; [email protected] (J.F.M.); [email protected] (G.S.d.H.) 4 Infectious Diseases Unit, Department of Medicine, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat 123, Oman; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (I.A.-B.); [email protected] (H.B.T.) 5 Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, 3584 CT Utrecht, The Netherlands; [email protected] 6 Department of Pathology, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat 123, Oman; [email protected] 7 Department of Radiology and Molecular Imaging, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat 123, Oman; [email protected] 8 Department of Surgery, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat -

Surgical Pathology and the Diagnosis of Invasive Visceral Yeast Infection

Di Carlo et al. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2013, 8:38 http://www.wjes.org/content/8/1/38 WORLD JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY SURGERY REVIEW Open Access Surgical pathology and the diagnosis of invasive visceral yeast infection: two case reports and literature review Paola Di Carlo1*, Gaetano Di Vita2, Giuliana Guadagnino1, Gianfranco Cocorullo3, Francesco D’Arpa3, Giuseppe Salamone3, Buscemi Salvatore2, Gaspare Gulotta3 and Daniela Cabibi1 Abstract Invasive mycoses are life-threatening opportunistic infections that have recently emerged as a cause of morbidity and mortality following general and gastrointestinal surgery. Candida species are the main fungal strains of gut flora. Gastrointestinal tract surgery might lead to mucosal disruption and cause Candida spp. to disseminate in the bloodstream. Here we report and discuss the peculiar clinical and morphological presentation of two cases of gastrointestinal Candida albicans lesions in patients who underwent abdominal surgery. Although in the majority of cases reported in the literature, diagnosis was made on the basis of microbiological criteria, we suggest that morphological features of fungi in histological sections of appropriate surgical specimens could help to detect the degree of yeast colonization and identify patients at risk of developing severe abdominal Candida infection. Better prevention and early antifungal treatments are highlighted, and relevant scientific literature is reviewed. Keywords: Surgical pathology, Gastrointestinal candidiasis, Diagnosis Introduction Several studies conducted over the last two decades Invasive mycoses are important healthcare-associated in- have shown that gastrointestinal surgeries are associated fections, and have become an increasingly frequent prob- with an increased risk of fungemia, and patients admit- lem in immunocompromised and severely ill patients [1]. -

Article Download (19)

wjpls, 2021, Vol. 7, Issue 6, 187-191. Review Article ISSN 2454-2229 Barot et al. World Journal of Pharmaceutical World Journaland Life of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Life Science WJPLS www.wjpls.org SJIF Impact Factor: 6.129 ITRACONAZOLE: THE INHIBITOR OF LANOSTEROL 14-ALPHA-DEMETHYLASE IN MUCORMYCOSIS *1Maitri Barot, 1Naiya Patel, 1Pruthviraj Chaudhary, 1Dr. C. N. Patel and 2Dr. Dhrubo Jyoti Sen 1Shri Sarvajanik Pharmacy College, Gujarat Technological University, Arvind Baug, Mehsana-384001, Gujarat, India. 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, Techno India University, Salt Lake City, Sector‒V, EM‒4, Kolkata‒700091, West Bengal, India. Corresponding Author: Maitri Barot Shri Sarvajanik Pharmacy College, Gujarat Technological University, Arvind Baug, Mehsana-384001, Gujarat, India. Article Received on 21/04/2021 Article Revised on 11/05/2021 Article Accepted on 01/06/2021 ABSTRACT Mucormycosis previously called zygomycosis, also known as black fungus, is a serious fungal infection, usually in people with reduce ability to fight infection.it is caused by the group of molds called mucoromycetes these molds live through the environment. In this review, based on the current understanding of the disease. It has been observed that itraconazole, as an antifungal medicine used in the treatment of mucormycosis, its work by slowing the growth of fungi that causes infection, or by killing yeast or fungi. It’s also having some role as anti-viral activity, and as an anti-cancer medicine because of the anti-viral activity, it can used in the treatment of covid-19 and also used in the cancer treatment. KEYWORDS: Mucormycosis; zygomycosis; itraconazole. INTRODUCTION Itraconazole [CAS: 84625-61-6] is an antifungal Description: Belongs to the class of organic compounds medication that is used in adults to treat infection caused known as phenylpiperazines. -

WO 2013/038197 Al 21 March 2013 (21.03.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/038197 Al 21 March 2013 (21.03.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: Geir [NO/NO]; Bj0rndalen 81, N-7072 Heimdal (NO). A01N 43/16 (2006.01) A01N 43/653 (2006.01) MYRVOLD, Rolf [NO/NO]; 0vre Gjellum vei 28, N- A61K 31/734 (2006.01) A01P 3/00 (2006.01) 1389 Heggedal (NO). A01N 43/90 (2006.01) (74) Agent: DEHNS; St Bride's House, 10 Salisbury Square, (21) International Application Number: London EC4Y 8JD (GB). PCT/GB20 12/052274 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (22) International Filing Date kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, 14 September 2012 (14.09.2012) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (25) English Filing Language: DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (26) Publication Language: English HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (30) Priority Data: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 1116010.8 15 September 201 1 (15.09.201 1) GB NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): AL- RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, GIPHARMA AS [NO/NO]; Industriveien 33, N-1337 TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, Sandvika (NO). -

Basidiobolomycosis: a Rare Case Report

Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, (2008) 26(3): 265-79 Case Report BASIDIOBOLOMYCOSIS: A RARE CASE REPORT We report a rare case of basidiobolomycosis seen in an 11-year-old no associated headache, vomiting, visual disturbance, girl from North-Eastern part of India. She presented with complaints aural fullness. She was not a diabetic and had no signs of bilateral nasal block and nasal discharge for seven-eight months. and symptoms suggestive of immunocompromised status. CT scan of sinuses revealed polypoidal mass in all the sinuses with There was no similar illness in the family. extradural extension. The tissue biopsy examined histopathologically and microbiologically, revealed Basidiobolus ranarum. Her systemic examination was non-signiÞ cant. On local Key words: Basidiobolomycosis, basidiobolus ranarum examination, there was signiÞ cant increase in intercanthal distance and broadening of the nose. Her visual acuity and Basidiobolus species are Þ lamentous fungi belonging visual Þ elds were normal. Endoscopy examination revealed to the order Entomophthorales. Unlike other zygomycetes, multiple dirty grayish polypoidal mass in both sides of Basidiobolus species causes subcutaneous zygomycosis nasal cavity displacing the middle turbinate with concha in healthy individuals.[1] Basidiobolus ranarum was bullosa on the right side. Oral cavity was normal but there Þ rst described as an isolate from frogs in 1886. It was was postnasal drip and congested post pharyngeal wall. later cultured from the intestinal contents and ultimately A contrast enhanced CT scan as shown in (Fig. 1) revealed the excreta of frogs.[2] It is commonly found in soil, soft tissue density in bilateral nasal cavity, ethmoids, decaying vegetable matter, and the gastrointestinal tracts maxillary antrum (with right side more involved than the of amphibians, reptiles, Þ sh and bats.[3] Basidiobolus is left) and sphenoid with extradural extension sparing the endemic in Uganda and certain other areas of Africa, India, orbit.