Demonstrating on Public Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mill's "Very Simple Principle": Liberty, Utilitarianism And

MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE": LIBERTY, UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM MICHAEL GRENFELL submitted for degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H^S £ S F 6SI6 ABSTRACT OF THESIS MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE'*: LIBERTY. UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM 1 The thesis aims to examine the political consequences of applying J.S. Mill's "very simple principle" of liberty in practice: whether the result would be free-market liberalism or socialism, and to what extent a society governed in accordance with the principle would be free. 2 Contrary to Mill's claims for the principle, it fails to provide a clear or coherent answer to this "practical question". This is largely because of three essential ambiguities in Mill's formulation of the principle, examined in turn in the three chapters of the thesis. 3 First, Mill is ambivalent about whether liberty is to be promoted for its intrinsic value, or because it is instrumental to the achievement of other objectives, principally the utilitarian objective of "general welfare". -

Intergovernmental Fiscal Immunity

BEST BEST & KRIEGER LLP A CALIFORNIA LIMITED LIABILITY PARTNERSHIP INCLUDING PROFESSIONAL CORPORATIONS RIVERSIDE ONTARIO LAWYERS (909) 686-1450 TH (909) 989-8584 WEST BROADWAY FLOOR ,, 402 , 13 ,, INDIAN WELLS SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA 92101-3542 ORANGE COUNTY (760) 568-2611 (619) 525-1300 (949) 263-2600 (619) 233-6118 FAX ,, SACRAMENTO BBKLAW COM . (916) 325-4000 CITY ATTORNEYS DEPARTMENT LEAGUE OF CALIFORNIA CITIES CONTINUING EDUCATION SEMINAR FEBRUARY 2003 WARREN DIVEN OF BEST BEST & KRIEGER LLP INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL IMMUNITY TOPIC OUTLINE TAXES Property Taxes Publicly Owned Property as Generally Exempt from Property Taxation Construction of the Constitutional Exemption Use of Publicly Owned Property Property Owned by a Public Agency Outside its Jurisdictional Boundaries Taxation of Possessory Interest Miscellaneous Statutory Provisions or Decisions Related to Property Taxation Sales and Use Tax Business License Tax Special Taxes Utility Users Tax CAPITAL FACILITIES FEES Capital Facilities Fees - Judicial History Legislative Response to San Marcos USER FEES ASSESSMENTS Pre-Proposition 218 Implied Exemption Public Use Requirement Post Proposition 218 - What Effect Proposition 218? City Attorneys Department League of California Cities Continuing Education Seminar February 2003 Warren Diven Partner INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL IMMUNITY1 The purpose of this paper is to review the concept of intergovernmental fiscal immunity, i.e., the exemption of one governmental entity from liability for the payment of taxes, assessments or fees levied or imposed by another governmental entity: • Where does such immunity exist? • How is such immunity created? • When does it apply? • What is the extent of such immunity? • What are the exceptions to the application of such immunity? This paper shall in turn review the application of intergovernmental fiscal immunity to: • Taxes; • Capital facility fees; • User fees; and • Assessments. -

A Study of the Conflicting Values When Private Property Rights Are

Private Property Rights vs. the Rights of Public Domain: A Study of the Conflicting Values when Private Property Rights are Abused by Hunters or Fishermen Ron Walsingham Abstract This research project examines traditions and cultures in Florida supporting the rights of private property ownership and the harvest of game or fish, whose ownership is common to all. The conflicts that arise from these deeply held values will be identified and discussed. This study presents the results of a questionnaire administered to wildlife law enforcement officers and interviews conducted with property owners and wildlife resource users throughout the state of Florida. This study will examine, from a current and historical perspective, the steps taken by the Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission to resolve this emotionally charged conflict. Introduction Urbanization of the state of Florida is proceeding at a rapid pace. In fact, Florida is currently one of the fastest growing states in our nation. From Florida’s Everglades to the rural Northwest Panhandle, communities are affected by this growth and development (Burnett, 1986). One effect of this rapid growth is alteration of traditional land uses. Undeveloped land, much of which was used by the public for recreation, has been developed to provide for the needs of the populace. Large tracts of land are required when these needs include housing, schools, hospitals, water, sewage, solid waste disposal and prisons, just to mention a few. Communities that were once considered small towns are now population centers with all of the problems associated with a large number of people. One aspect of growth seldom noticed by the urban community is the loss of undeveloped properties, lakes and streams previously available to the public for hunting and fishing. -

The Camouflaged Crime: Perceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2021 The Camouflaged Crime: erP ceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia Randi Miller East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Randi, "The Camouflaged Crime: erP ceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3919. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3919 This Thesis - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Camouflaged Crime: Perceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Criminal Justice East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Criminal Justice ______________________ by Randi Marie Miller May 2021 _____________________ Dustin Osborne, Ph.D., Chair Larry Miller, Ph.D. Chris Rush, Ph.D. Keywords: conservation officers, poaching, southern appalachia, rural crime ABSTRACT The Camouflaged Crime: Perceptions of Poaching in Southern Appalachia by Randi Marie Miller The purpose of this study was to explore perceptions of poaching within the Southern Appalachian Region. To date, little research has been conducted on the general topic of poaching and no studies have focused on this Region. Several research questions were pursued, including perceptions of poacher motivations, methods and concern regarding apprehension and punishment. -

Regulating the Use and Occupancy of Open Space and Other Public Property and Protecting Constitutional Rights Thursday, May 5, 2016 General Session; 2:15 – 4:15 P.M

Regulating the Use and Occupancy of Open Space and Other Public Property and Protecting Constitutional Rights Thursday, May 5, 2016 General Session; 2:15 – 4:15 p.m. Yibin Shen, Deputy City Attorney, Santa Monica DISCLAIMER: These materials are not offered as or intended to be legal advice. Readers should seek the advice of an attorney when confronted with legal issues. Attorneys should perform an independent evaluation of the issues raised in these materials. Copyright © 2016, League of California Cities®. All rights reserved. This paper, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without express written permission from the League of California Cities®. For further information, contact the League of California Cities® at 1400 K Street, 4th Floor, Sacramento, CA 95814. Telephone: (916) 658-8200. League of California Cities® 2016 Spring Conference Marriott, Newport Beach Notes:______________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ -

Chapter 7 Property Tax Exemptions Module Topics and Objectives

Rev. 1/21 CHAPTER 7 PROPERTY TAX EXEMPTIONS MODULE TOPICS AND OBJECTIVES A. TOPICS 1. Introduction to exemptions. 2. Exemptions for charitable, fraternal, veterans’ and religious organizations. 3. General requirements for personal exemptions. 4. Exemptions for seniors, surviving spouses and minors, veterans and blind persons. 5. Financial hardship exemption. 6. Tax deferrals for seniors and persons with temporary financial hardships. B. OBJECTIVES 1. Participants will learn the definition of exemption. 2. Participants will learn about the important exemptions to property. 3. Participants will learn about exemptions for persons. Assessment Administration: Law, Procedures and Valuation Property Tax Exemptions 7 - 1 Rev. 1/21 CHAPTER 7 PROPERTY TAX EXEMPTIONS MODULE 1.0 OVERVIEW AND DEFINITIONS 1.1 Exemptions An exemption is a release or discharge from the obligation to pay all or a portion of a local property tax. Exemptions are established by the legislature for particular categories of property or persons and are generally found in G.L. c. 59, § 5. However, a few are contained in other general laws and some are provided by court decisions. Exemption is a privilege and any claimant must demonstrate that it clearly qualifies. 1.1.1 Exempt Properties Properties that may qualify for exemption from local property taxes include public land and facilities, hospitals, schools, churches, and cultural institutions. 1.1.2 Exempt Persons Persons who may qualify for exemptions include disabled veterans, blind persons, surviving spouses, and seniors. There are also tax deferrals for seniors and those experiencing a temporary financial hardship. 1.2 Qualification Date Exempt status for real estate is determined as of July 1, which is the beginning of the fiscal year. -

7 Commodity Or Public Property?

7 Commodity or Public Property? Nils A. Nilsson The first scientific journals which started regularly publishing new ideas and results in an organised way were launched in 1665 in France and the United Kingdom. The idea was that by collecting new science in one place, scientists could save much work and effort by not having to distribute their results in the form of written letters. Moreover, as the journals recorded the exact dates of received material, it became easier to give credit appropriately. Previous to this, it was not always clear who had been the first to arrive at a certain result. Since then, the world has grown smaller, and today there are thousands of peer reviewed academic journals available both online and in print. However, a large fraction of these publications are available only through a subscription, which comes at a steep cost, and individuals outside of academia might feel reluctant to put up the money required for access. Whilst there are preprint servers out there, these are not peer reviewed, and articles published there may contain mistakes and inconsistencies. It is therefore imperative to have access to the publication in its final form, which means needing access to a journal, through a paywall. An engineering student from Germany, a schoolteacher from Sudan, or a decision maker from Japan, these are people who might want access to the latest research publications, but because of paywalls, will almost certainly have trouble finding what they need. If publications were available free of charge, these people, and many more would have instant access to the very forefront of human knowledge. -

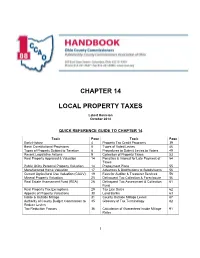

Chapter 14 Local Property Taxes

CHAPTER 14 LOCAL PROPERTY TAXES Latest Revision October 2014 QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE TO CHAPTER 14 Topic Page Topic Page Early History 4 Property Tax Credit Programs 39 Basic Constitutional Provisions 5 Types of Voted Levies 46 Types of Property Subject to Taxation 8 Procedures to Submit Levies to Voters 49 Recent Legislative Actions 9 Collection of Property Taxes 53 Real Property Appraisal & Valuation 14 Penalties & Interest for Late Payment of 54 Taxes Public Utility Personal Property Valuation 14 Prepayment Plans 55 Manufactured Home Valuation 17 Advances & Distributions to Subdivisions 56 Current Agricultural Use Valuation (CAUV) 19 Fees for Auditor & Treasurer Services 56 Mineral Property Valuation 25 Delinquent Tax Collection & Foreclosure 56 Real Estate Assessment Fund (REA) 26 Delinquent Tax Assessment & Collection 61 Fund Real Property Tax Exemptions 29 Tax Lien Sales 62 Appeals of Property Valuations 30 Land Banks 63 Inside & Outside Millage 31 County Outside Millage Levies 67 Authority of County Budget Commission to 35 Glossary of Tax Terminology 82 Reduce Levies Tax Reduction Factors 36 Calculation of Guaranteed Inside Millage 91 Rates 1 14.01 INTRODUCTION Property taxes form the financial base of many local government services. For counties, the board of county commissioners is the county’s taxing authority and has the authority and responsibility to place most of the statutorily authorized county property tax levies on the ballot for consideration of the electors. In addition, a county commissioner is a member of the county -

Marshall: a Professional Economist Guards the Purity of His Discipline

4 Marshall: A Professional Economist Guards the Purity of His Discipline / BY ROBERT F. HEBERT I. Background In 1883 the name of Henry George was more famiMar on both sides of the Atlantic than that of Alfred Marshall. Marshall was to achieve lasting recognition a decade later as the foremost British economist of his day, but George's Progress and Poverty had already achieved an unusual measure of success for a work in political economy. Sales of that volume reached one hundred thousand in the British Isles a few years after its appearance in a separate English edition. This popularity (in a period when "best sellers"- were less well received than now) was undoubtedly one measure of the British sentiment for land reform—a sentiment that had been carefully nurtured for several decades, especially by John Stuart Mill and Alfred R. Wallace. Additional sympathy for George and his ideas was also stirred by his controversial arrests in Ireland in 1882.' Most economists of the late nineteenth century paid little attention to the lively subject of land reform, but Marshall was an exception. Intellectually, he was akin to John Stuart Mill—both were simultaneously attracted and repelled by socialist doctrine. Marshall admitted a youthful "tendency to socialism," which he later rejected as unrealistic and perverse in its effect on economic incentives and human character .2 His early writings, however, clearly identify him as a champion of the working class. Marshall cultivated this reputation in his correspondence, and he continued to take socialism seriously, even after his "flirtation" with it ended. In the winter of 1883 Marshall gave a series of public lectures at Bristol on "Henry George's subject of Progress and Poverty." These lectures have only recently become accessible to American readers.' In retrospect they appear to be Marshall's first deliberate attempt to renounce his socialist "ties," such as they were. -

14Th Amendment US Constitution

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS GUARANTEED PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES OF CITIZENSHIP, DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION CONTENTS Page Section 1. Rights Guaranteed ................................................................................................... 1565 Citizens of the United States ............................................................................................ 1565 Privileges and Immunities ................................................................................................. 1568 Due Process of Law ............................................................................................................ 1572 The Development of Substantive Due Process .......................................................... 1572 ``Persons'' Defined ................................................................................................. 1578 Police Power Defined and Limited ...................................................................... 1579 ``Liberty'' ................................................................................................................ 1581 Liberty of Contract ...................................................................................................... 1581 Regulatory Labor Laws Generally ...................................................................... 1581 Laws Regulating Hours of Labor ........................................................................ 1586 Laws Regulating Labor in Mines ....................................................................... -

The Public Trust Doctrine

The Wildlife Society 5410 Grosvenor Lane, Suite 200 Bethesda, MD 20814-2144 301-897-9770 301-530-2471 Fax [email protected] Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 444 North Capitol Street, NW Suite 725 Washington, DC 20001 202-624-7890 202-624-7891 Fax [email protected] Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 522 Notre Dame Court Cheyenne, WY 82009 The Public Trust Doctrine 307-638-1470 307-638-1470 Fax Implications for Wildlife Management and [email protected] Conservation in the United States and Canada Wildlife Management Institute 1440 Upper Bermudian Road Gardners, PA 17324 Technical Review 10-01 717-677-4480 September 2010 [email protected] The Wildlife Society The Public Trust Doctrine: Implications for Wildlife Management and Conservation in the United States and Canada Technical Review 10-01 September 2010 “Defenders of the short-sighted men who in their greed and selfishness will, if permitted, rob our country of half its charm by their reckless extermination of all useful and beautiful wild things sometimes seek to champion them by saying that “the game belongs to the people.” So it does; and not merely to the people now alive, but to the unborn people. The “greatest good for the great- est number” applies to the number within the womb of time, compared to which those now alive form but an in- significant fraction. Our duty to the whole, including the unborn generations, bids us to restrain an unprincipled present-day minority from wasting the heritage of these unborn generations. The movement for the conservation of wildlife and the larger movement for the conservation of all our natural resources are essentially democratic in spirit, purpose, and method.” Theodore Roosevelt (1916) Armed for a hunt, Theodore Roosevelt makes ready to ride, circa 1900. -

Hobbes to Rousseau: Inequality, Institutions, and Development

IZA DP No. 1450 Hobbes to Rousseau: Inequality, Institutions, and Development Matteo Cervellati Piergiuseppe Fortunato Uwe Sunde DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER January 2005 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Hobbes to Rousseau: Inequality, Institutions, and Development Matteo Cervellati University of Bologna Piergiuseppe Fortunato University of Bologna Uwe Sunde IZA Bonn and University of Bonn Discussion Paper No. 1450 January 2005 (updated February 2006 – old version available at ftp://ftp.iza.org/dps/dp1450_ov.pdf) IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author.