This History Was Originally Written by Graham Tanner, OUAC Coach From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathfinders Club Is Founded Fr. Walsh Talks on Russian

No. 21 VOL. V GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D. C„ MARCH 13, 1924 PATHFINDERS CLUB COPY OF TELEGRAM SENT TO PRESIDENT OF BARONSERGEKORFF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY AND TO PRESIDENT DIES SUDDENLY IS FOUNDED OF JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY. Eighty Men Gather to Form New Russian Nobleman Stricken in "Georgetown University unites with sister University in Society—Fr. Quigley, S. J., Is common sorrow at death of beloved Professor Baron Korff. Stricken in Midst of Seminar—Burial at Sponsor of Club to Further classroom of School of Foreign Service, he leaves precious memories, for Rock Creek Cemetery Monday. Students' Interest in a Voca- faculty and student body, of a true scholar and distinguished gentleman. Learned Lecturer Enjoyed tion — Big Professional and Cause of both universities in efforts towards an enlightened understanding Brilliant Career as Statesman of international relations suffers immeasurably by his death. Business Men to Address and Educator—Fr. Walsh Pays JOHN B. CREEDON, Members. President Georgetown University. Tribute to Former Colleague. On Monday evening, March 10, in Baron Serge A. Korff, professor of Room H, a large number of students as- History in the Foreign Service School, sembled to organize a club which is FR. WALSH TALKS CAST FOR HAMLET member of the Russian nobility and inter- unique in the annals of Georgetown. Mr. nationally known as a leader in political John H. Daly, president of the class of ON RUSSIAN DECIDED UPON science and as a professor of Compara- 1924, presided as chairman of the meet- tive Government, died from a stroke of apoplexy at his residence in 15th Street ing. -

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

The Oxford V Cambridge Varsity Sports

Fixtures 2013 Changing Times 1 The format of the Achilles Annual Report went largely un‐ ACHILLES CLUB changed from 1920 unl the 1960’s (and if any one can Saturday 16th February ‐ Varsity Field Events & Relays ‐ Lee Valley unearth the lost Reports of 1921‐23 we would be thrilled!). 23‐24th February ‐ BUCS Indoors ‐ Sheffield EIS It was then a small A5 booklet, containing a couple of pages ANNUAL REPORT Saturday 9th March – CUAC Dinner describing the Club’s acvies during the year, the results of the Varsity Match and other compeons, and a compre‐ 13th‐23rd March—OUAC Warm Weather Training ‐ Portugal hensive list of members and their addresses. 24th‐31st March ‐ CUAC Warm Weather Training‐ Malta 3rd‐19th April ‐ Oxford & Cambridge US Tour 6th April ‐ Oxford & Cambridge v Penn & Cornell ‐ Cornell www.achilles.org th 2012 15 April – American Achilles Foundaon Dinner, at Harvard ‐ contact Tom Blodge [email protected] 16th April ‐ Oxford 7 Cambridge v Harvard & Yale – Harvard Saturday 27th April ‐ Achilles: Kinnaird/Sward Meeng – Kingston‐upon‐ Thames Sunday 28th April ‐ CUAC Sports ‐ Wilberforce Road 4‐6th May ‐ BUCS Outdoors ‐ Bedford Saturday 18th May ‐ Varsity Sports ‐ Wilberforce Road, Cambridge During the 1970’s and early 1980’s publicaon lapsed, and Achilles Dinner, at St Catharine’s. Chief Guest: Jon Ridgeon. Contact Tom Dowie when I revived it in 1986 it was in A4 format. Over the [email protected] years, as technology and my IT skills have improved I’ve Wednesday 29th May ‐ Achilles v Loughborough ‐ Loughborough sought to expand the content and refine its presentaon, Saturday 29 June ‐ Achilles, LICC Round One ‐ Allianz Park (formerly but always maintaining the style and identy of the Reports Copthall Stadium) of the Club’s first 50 years. -

Melbourne University Sport

Blues Advisory Group Terms of Reference 1. Preamble Sport has always had a special significance at the University of Melbourne, particularly the success of our student-athletes in their endeavours in representing the University against other institutions. Blues were first awarded by the University for cricket and rowing for sporting contests in 1870. They were adopted along the lines of those awarded by Oxford and Cambridge universities where students were selected for annual sporting competitions with Full Blues awarded for major sports and Half Blues awarded for minor sports. Similar principles still apply to the awarding of Blues today with Full Blues awarded for a student’s outstanding sporting achievement whilst representing the University in approved inter-university competitions, and Half Blues awarded where sporting performance is excellent, but not of a Full Blue standard. 2. Composition The Blues Advisory Group is appointed by the University of Melbourne’s Board of Sport (the Board) and is comprised as follows: 2.1. Eight members who hold a Blue, Half Blue or Distinguished Service Award; and a Chair as nominated by the Director of Sport The Sport Coordinator, or designated University Team Manager for the year, will attend to provide secretariat support. 3. Term Blues Advisory Group members will: 3.1. Be appointed for a three-year term and may be reappointed for two further terms; and 3.2. Vacancies will be advertised on the MU Sport website and to clubs via the Club Operations Memo as and when appropriate. 4. Blues Advisory Group Duties The Blues Advisory Group will: 4.1. -

Etn1964 Vol11 02

:~/~r-' .;__-,'/>~~"":-\-·.__ : f-:"'-, • •... •·. < ;r . •·.. ·• ?~ 'TRACK ' . if SupplementingTRACK & FIELDNEWS twice monthly. rt_v_o_l_. -1-l,-.-N-o-·.-2---------------------A-u_gu_st-27-· ,-1-96_4_________ .......,_____________ --=, __ I Final Olympic Trials Predictions Foreign News by Dick Drake t' The following dope sheet represents the author's predicted ( With assistance from Sven Ivan Johansson) ~;,<:order of finish for all the competitors in the Final Olympic Trials. ESSEN, WEST GERMANY, 100, Obersiebrasse 10.3; 2. Kmck r:·cThe second column indicates best mark this season and the third is enberg 10.3. HT, Beyer (19 years old) 221'½". ( ~he athlete'; place and mark in the Olympic Semi Trials. In some LANDAU, WEST GERMANY, JT, Stumpp 259'3½". Wilke 10.2w. (:;~cases, the athletes were advanced by the Olympic committee, in LEIPZIG, EAST GERMANY, 800, Ulrich 1:48.5. TJ, Thierfel z;;.·.which i.nstances the word "passed" is used. Comments on each ath der 52'7½". ~ ';Jete follow aa well as general comments for each event. , SIENNE, ITALY, 100, Figuerola (Cuba) 10.2. HH, Ottoz 14.1; 2. Mazza 12.1. HJ, Bogliatto 6'91". ¼~~:t~-1· 00 M.ET· ER· DASH SOFIA, BULGARIA, PV, Khlebarov 15'10½"; 2. Butcher (Pol) ("': :Bob Hayes 10. 2 passed He doesn't lose even injured 15'5". DT, Artarski 185'4". Hf, Rut (Pol) 218'1". 400R, Bulgaria r .'.Charles Greene 10 .3 3-10 .2w If healthy, could be there 40.1. ~,t~·.T:rentonJackson 10 11 1-10.lw Powerfulrunner;goodstarter PRAGUE, 1600R, Czechoslovakia 3:07 .2. ;\;Darel Newman 10.2 6t-10.3w Tailed off in national meets DUSSELOORF, 400, Kindger 46.6. -

Sports Guide 2019-20 Clubs • Facilities • Competitions • Membership Contents

Sports Guide 2019-20 Clubs • Facilities • Competitions • Membership Contents 1 Welcome - 9 Dance 16 Mountaineering 23 Shooting – Rifle Nick Brooking Dancesport Netball Shooting – Small-bore 2 Sports Service Eton Fives Orienteering Ski and Snowboard Contacts Fencing Polo Squash Rackets 3 Competitions 10 Football (Men) 18 Pool and Snooker 24 Swimming 4 American Football Football (Women) Powerlifting Table Tennis Archery Gliding Rackets Taekwondo Athletics Golf Rambling Lawn Tennis Australian Rules 11 Gymnastics 19 Real Tennis 25 Touch Rugby 5 Automobile Handball Riding Trampoline Badminton Hillwalking Rowing (Men) Triathlon Basketball (Men) Hockey Rowing (Women) Ultimate Basketball (Women) 13 Ice Hockey (Men) 20 Rowing – (Lightweight 26 Volleyball 6 Boxing Ice Hockey (Women) Men) Water Polo Canoe Jiu-Jitsu Rugby Fives Windsurfing Cheerleading Judo Rugby League – see Sailing Chess 14 Karate Rugby Union (M) Yachting 8 Cricket (Men) Kendo 21 Rugby Union (W) Disability Mulitsport Cricket (Women) Kickboxing Sailing 28 Sports Facilities Cross County Korfball Shooting 29 Support & Services Cycling 15 Lacrosse (Men) – Clay Pigeon Lacrosse (Mixed) Shooting – Revolver and Pistol Lacrosse (Women) Modern Pentathlon Welcome to the University of Cambridge, and I hope you find this guide to our University Sports Clubs helpful. With over 75 Sports Clubs and Societies, Cambridge offers you a diverse range of competitive and recreational sport. Whether your ambition is to perform at the highest level or to start playing a sport you have not played before, there will be great opportunities for you during your time here. Many University teams compete against their peers at other Universities in BUCS competitions throughout the season; some play in National or Regional leagues and there are also possibilities for individual representation. -

Vetrunner June 2008.Pub

VETRUNNER Email: [email protected] ISSN 1449-8006 Vol. 29 Issue 10 — June 2008 MAJURA — cool & crisp but a warm inner glow at the finish (Handicap report for 27th April 2008 by Geoff Barker) home in 19th position to claim the bronze medal. Emma found it rewarding to receive a medal especially after her Even though the balloons could not fly, the ACT Vets increased new handicap, and hopes it is an indication that (Masters?) flew around the Majura course like there was no her fitness level is improving each month. It was the most tomorrow. It was a cool, crisp morning with a bit of a chill challenging run Emma has attempted in her three months wind reminding us all that winter is here. Everyone also of running. She found the start the most difficult and warmed to see Marco Falzarano – albeit briefly do a bit of a thought the last bit before the turn ‘cruel’. However she jog/walk up the first 100 metres. And the absence of Alan enjoyed the end. She now feels competitive with Anthony, Duus, Jane Bell, Ros Pilkinton and John Littler has been Mike and Robyn and hopes it will not be too long before she noted! overtakes them all in the family medal tally. Daughter Mollie, who uses the childcare facilities, is not included. FRYLINK series Heather Koch, who was first over the line in April, First over the line was Carol Bennett, who became came home in 25th position. another of these women who simply ran off into the pale Tony Harrison, one of the most important people at blue cold day, and has not been seen since. -

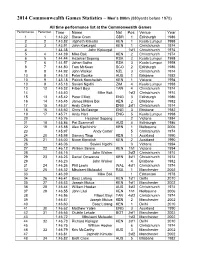

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's 800M

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 800m (880yards before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 1:43.22 Steve Cram GBR 1 Edinburgh 1986 2 2 1:43.82 Japheth Kimutai KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 3 3 1:43.91 John Kipkurgat KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 4 1:44.38 John Kipkurgat 1sf1 Christchurch 1974 5 4 1:44.39 Mike Boit KEN 2 Christchurch 1974 6 5 1:44.44 Hezekiel Sepeng RSA 2 Kuala Lumpur 1998 7 6 1:44.57 Johan Botha RSA 3 Kuala Lumpur 1998 8 7 1:44.80 Tom McKean SCO 2 Edinburgh 1986 9 8 1:44.92 John Walker NZL 3 Christchurch 1974 10 9 1:45.18 Peter Bourke AUS 1 Brisbane 1982 10 9 1:45.18 Patrick Konchellah KEN 1 Victoria 1994 10 9 1:45.18 Savieri Ngidhi ZIM 4 Kuala Lumpur 1998 13 12 1:45.32 Filbert Bayi TAN 4 Christchurch 1974 14 1:45.40 Mike Boit 1sf2 Christchurch 1974 15 13 1:45.42 Peter Elliott ENG 3 Edinburgh 1986 16 14 1:45.45 James Maina Boi KEN 2 Brisbane 1982 17 15 1:45.57 Andy Carter ENG 2sf1 Christchurch 1974 18 16 1:45.60 Chris McGeorge ENG 3 Brisbane 1982 19 17 1:45.71 Andy Hart ENG 5 Kuala Lumpur 1998 20 1:45.76 Hezekiel Sepeng 2 Victoria 1994 21 18 1:45.86 Pat Scammell AUS 4 Edinburgh 1986 22 19 1:45.88 Alex Kipchirchir KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 23 1:45.97 Andy Carter 5 Christchurch 1974 24 20 1:45.98 Sammy Tirop KEN 1 Auckland 1990 25 21 1:46.00 Nixon Kiprotich KEN 2 Auckland 1990 26 1:46.06 Savieri Ngidhi 3 Victoria 1994 27 22 1:46.12 William Serem KEN 1h1 Victoria 1994 28 1:46.15 John Walker 2sf2 Christchurch 1974 29 23 1:46.23 Daniel Omwanza KEN 3sf1 Christchurch -

See Partial Accord in Test Ban Talks

****** Distribution ^, W*5 t* ».. Fair U- mt mimmmm. Urn toafebt 21,350 Me. Wednesday, fair, little ) Independent Daily [ Chance in temperature. Sea \_ nonBAtTUKVoanauT-trr.mi J Wtatber, Page 2. DIAL SH I -0010 VOL. 86; NO. 12 luu.a iij, Units umofh Friday. Mcend CUn Po»t»it RED BANK, N. J., MONDAY, JULY 15, 1963 PAGE ONE Paid lUd Bank ul u AdiltteUl KtlUni Oiucuu 7c PER COPY Rockefeller Challenges Goldwater WASH»JGTON (AP)-Gov. Nel will never be found in a party son A. Rockefeller has challenged of extremism, a party of section- See Partial Accord Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., to alism, a party of racism, a party an all-out liberal vs. conservative that disclaims responsibility for fight for the 1964 Republican pres- most of the population before it idential nomination. even starts its campaign for their In a policy statement tanta- support." mount to announcing his candi- Goldwater, who was not named dacy, the New York governor said in the statement, made no imme- In Test Ban Talks Sunday the Goldwater strategy is diate response. But associates to try to weld conservative, South- said they interpreted Rockefeller's BULLETIN ban. Underground tests were ex- North Atlantic Treaty Organiza- Western observers expected the ern and Western support while attack- as a declaration of war MOSCOW (AP) — Special empted to avoid the thorny issue tion and the Communist Warsaw opening round ol the secret three- they were certain the senator of on-site inspection. writing off Northern states. This, envoys from President Kennedy Pact alliance. He said the test ban power talks at the Kremlin would would accept, even though he re- Partial Ban and the non-aggression pact should clarify whether Khrushcfiev would Rockefeller said, "would not only and Prime Minister Macmillan main* an unannounced belliger- At the time Khrushchev ap- be signed simultaneously, but U.S.insist on the two treaties as « defeat the Republican party in opened negotiations with Pre- 1964 but would destroy it alto- ent. -

Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912– 1921 By: Adam Berg, Mark Dyreson Berg, A

The Flying Finn's American Sojourn: Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912– 1921 By: Adam Berg, Mark Dyreson Berg, A. & Dyreson, M. (2012). The Flying Finn’s American Sojourn: Hannes Kolehmainen in the United States, 1912-1921. International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(7), 1035-1059. doi: 10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in International Journal of the History of Sport on 15 May 2012, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 Made available courtesy of Taylor & Francis: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.679025 ***© Taylor & Francis. Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Taylor & Francis. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** Abstract: Shortly after he won three gold medals and one silver medal in distance running events at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, Finland's Hannes Kolehmainen immigrated to the United States. He spent nearly a decade living in Brooklyn, plying his trade as a mason and dominating the amateur endurance running circuit in his adopted homeland. He became a naturalised US citizen in 1921 but returned to Finland shortly thereafter. During his American sojourn, the US press depicted him simultaneously as an exotic foreign athlete and as an immigrant shaped by his new environment into a symbol of successful assimilation. Kolehmainen's career raised questions about sport and national identity – both Finnish and American – about the complexities of immigration during the floodtide of European migration to the US, and about native and adopted cultures in shaping the habits of success. -

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S

Indoor Track and Field DIVISION I MEN’S Highlights Florida claims top spot in men’s indoor track: At the end of the two-day gamut of ups and downs that is the Division I NCAA Indoor Track and Field National Champion- ships, Florida coach Mike Holloway had a hard time thinking of anything that went wrong for the Gators. “I don’t know,” Holloway said. “The worst thing that happened to me was that I had a stomachache for a couple of days.” There’s no doubt Holloway left the Randal Tyson Track Center feeling better on Saturday night. That’s because a near-fl awless performance by the top-ranked Gators re- sulted in the school’s fi rst indoor national championship. Florida had come close before, fi nishing second three times in Holloway’s seven previous years as head coach. “It’s been a long journey and I’m just so proud of my staff . I’m so proud of my athletes and everybody associated with the program,” Holloway said. “I’m almost at a loss for words; that’s how happy I am. “It’s just an amazing feeling, an absolutely amazing feeling.” Florida began the day with 20 points, four behind host Arkansas, but had loads of chances to score and didn’t waste time getting started. After No. 2 Oregon took the lead with 33 points behind a world-record performance in the heptathlon from Ashton Eaton and a solid showing in the mile, Florida picked up seven points in the 400-meter dash. -

Ok-Fr-Belgian-Delegations-Summer

Délégations belges aux Jeux Olympiques d’été 34ème Olympiade d’été – Los Angeles, USA – 2028 33ème Olympiade d’été – Paris, France – 2024 32ème Olympiade d’été – Tokyo, Japon – 2020 31ème Olympiade d’été – Rio de Janeiro, Brésil – 2016 30ème Olympiade d’été – Londres, Angleterre – 2012 29ème Olympiade d’été – Pékin, Chine – 2008 28ème Olympiade d’été – Athènes, Grèce – 2004 27ème Olympiade d’été – Sydney, Australie – 2000 26ème Olympiade d’été – Atlanta, USA – 1996 25ème Olympiade d’été – Barcelone, Espagne – 1992 24ème Olympiade d’été – Séoul, Corée du Sud – 1988 23ème Olympiade d’été – Los Angeles, USA – 1984 22ème Olympiade d’été – Moscou, Russie – 1980 21ème Olympiade d’été – Montréal, Canada – 1976 20ème Olympiade d’été – Munich, Allemagne – 1972 19ème Olympiade d’été – Mexico, Mexique – 1968 18ème Olympiade d’été – Tokyo, Japon – 1964 17ème Olympiade d’été – Rome, Italie – 1960 16ème Olympiade d’été : Jeux équestres – Stockholm, Suède - 1956 16ème Olympiade d’été – Melbourne, Australie – 1956 15ème Olympiade d’été – Helsinki, Finlande – 1952 14ème Olympiade d’été – Londres, Angleterre – 1948 13ème Olympiade d’été – Londres, Angleterre – 1944 12ème Olympiade d’été – Tokyo, Japon – 1940 11ème Olympiade d’été – Berlin, Allemagne – 1936 10ème Olympiade d’été – Los Angeles, USA – 1932 9ème Olympiade d’été – Amsterdam, Pays-Bas – 1928 8ème Olympiade d’été – Paris, France – 1924 7ème Olympiade d’été – Anvers, Belgique – 1920 6ème Olympiade d’été – Berlin, Allemagne – 1916 5ème Olympiade d’été – Stockholm, Suède – 1912 4ème Olympiade d’été