World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook of Statistics Guntur District 2015 Andhra Pradesh.Pdf

Sri. Kantilal Dande, I.A.S., District Collector & Magistrate, Guntur. PREFACE I am glad that the Hand Book of Statistics of Guntur District for the year 2014-15 is being released. In view of the rapid socio-economic development and progress being made at macro and micro levels the need for maintaining a Basic Information System and statistical infrastructure is very much essential. As such the present Hand Book gives the statistics on various aspects of socio-economic development under various sectors in the District. I hope this book will serve as a useful source of information for the Public, Administrators, Planners, Bankers, NGOs, Development Agencies and Research scholars for information and implementation of various developmental programmes, projects & schemes in the district. The data incorporated in this book has been collected from various Central / State Government Departments, Public Sector undertakings, Corporations and other agencies. I express my deep gratitude to all the officers of the concerned agencies in furnishing the data for this publication. I appreciate the efforts made by Chief Planning Officer and his staff for the excellent work done by them in bringing out this publication. Any suggestion for further improvement of this publication is most welcome. GUNTUR DISTRICT COLLECTOR Date: - 01-2016 GUNTUR DISTRICT HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS – 2015 CONTENTS Table No. ItemPage No. A. Salient Features of the District (1 to 2) i - ii A-1 Places of Tourist Importance iii B. Comparision of the District with the State 2012-13 iv-viii C. Administrative Divisions in the District – 2014 ix C-1 Municipal Information in the District-2014-15 x D. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 SURVEY NO.1053 & 1054, ATS SHOPPING COMPLEX, ANDAMAN TRUNK ROAD, GARACHAR MA, PORT ANDAMAN BLAIR, AND SOUTH NICOBAR ANDAMAN ISLAND ANDAMAN Garacharma -744105 PORT BLAIR CNRB000521403192-251114 Krishna ANDAMAN House, AND Aberdeen NICOBAR PORT BLAIR Bazar, Port ISLAND ANDAMAN ANDAMAN Blair 744 104 PORT BLAIR CNRB000118503192-233085 [email protected] CANARA BANK, H NO 9 - 420, TEACHERS COLONY, DASNAPUR - 504001, ADILABAD DIST, ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH ADILABAD DASNAPUR PRADESH ADILABAD CNRB0003872 [email protected] H No.4-47/5, Bellampally Road MANCHERIA L 504208 , ANDHRA MANCHERIA ADILABAD MANCHERIY cb4169@can PRADESH ADILABAD L DIST., A P AL CNRB0004169arabank.com Main Road NIRMAL ANDHRA ADILABAD cb4176@can PRADESH ADILABAD Nirmal DISTRICT NIRMAL CNRB0004176arabank.com DOOR NO 11/176,SUBH ASH ROAD,, NEAROLD TOWN BRIDGE,, ANDHRA ANANTAPUR 08554 PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR - 515001. ANANTAPUR CNRB0000659-222464 [email protected] BANGALORE - HYDERABAD HIGHWAY,, CHENNAKOT HAPALLI , DIST ANDHRA CHENNEKOT ANANTHPUR CHENNAKOT PRADESH ANANTAPUR HAPALLI (A P) -515 101 HAPALLI CNRB000013808559-240328 [email protected] MANJU COMPLEX,, ANDHRA DHARMAVAR DHARMAVAR DHARMAVAR PRADESH ANANTAPUR AM AM 515671, , AM CNRB000085108559-223029 [email protected] LALAPPA GARDEN, NH - 7,, GARLADINN E , DIST ANDHRA GARLADINN ANANTPUR, GARLADINN PRADESH ANANTAPUR E (A P) - 515731 E CNRB000097908551-286430 [email protected] D.NO:1/30 KOTAVEEDHI RAPTHADU MANDAL ANANTAPUR DISTRICT ANDHRA -

Handbook of Statistics Guntur District 2014 Andhra Pradesh.Pdf

Sri. Kantilal Dande, I.A.S., District Collector & Magistrate, Guntur. PREFACE I am glad that the Hand Book of Statistics of Guntur District for the year 2013-14 is being released. In view of the rapid socio-economic development and progress being made at macro and micro levels the need for maintaining a Basic Information System and statistical infrastructure is very much essential. As such the present Hand Book gives the statistics on various aspects of socio-economic development under various sectors in the District. I hope this book will serve as a useful source of information for the Public, Administrators, Planners, Bankers, NGOs, Development Agencies and Research scholars for information and implementation of various developmental programmes, projects & schemes in the district. The data incorporated in this book has been collected from various Central / State Government Departments, Public Sector undertakings, Corporations and other agencies. I express my deep gratitude to all the officers of the concerned agencies in furnishing the data for this publication. I appreciate the efforts made by Chief Planning Officer and his staff for the excellent work done by them in bringing out this publication. Any suggestion for further improvement of this publication is most welcome. GUNTUR DISTRICT COLLECTOR Date:20-08-2015 GUNTUR DISTRICT HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS – 2014 CONTENTS Table No. ItemPage No. A. Salient Features of the District (1 to 2) i - ii A-1 Places of Tourist Importance iii B. Comparison of the District with the State 2013-14 iv-viii C. Administrative Divisions in the District – 2013-14 ix C-1 Municipal Information in the District-2013-14 x D. -

District Census Handbook, Guntur, Part XII-A & B, Series-2

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GUNTUR PARTS XII - A &. B VILLAGE &. TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE It TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT R.P.SINGH OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1995 FOREWORD Publication of the District Census Handbooks (DCHs) was initiated after the 1951 Census and is continuing since then with .some innovations/modifications after each decennial Census. This is the most valuable district level publication brought out by the Census Organisation on behalf of each State Govt./ Uni~n Territory a~ministratio~. It Inte: alia Provides data/information on· some of the baSIC demographic and soclo-economlc characteristics and on the availability of certain important civic amenities/facilities in each village and town of the respective ~i~tricts. This pub~i~ation has thus proved to be of immense utility to the pJanners., administrators, academiCians and researchers. The scope of the .DCH was initially confined to certain important census tables on population, economic and socia-cultural aspects as also the Primary Census Abstract (PCA) of each village and town (ward wise) of the district. The DCHs published after the 1961 Census contained a descriptive account of the district, administrative statistics, census tables and Village and Town Directories including PCA. After the 1971 Census, two parts of the District Census Handbooks (Part-A comprising Village and Town Directories and Part-B com~iSing Village and Town PCA) were released in all the States and Union Territories. Th ri art (C) of the District Census Handbooks comprising administrative statistics and distric census tables, which was also to be brought out, could not be published in many States/UTs due to considerable delay in compilation of relevant material. -

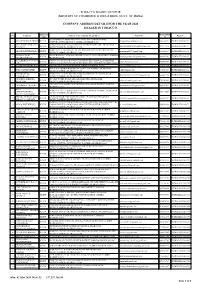

Print Report

TOBACCO BOARD::GUNTUR (MINISTRY OF COMMERCE & INDUSTRIES, GOVT. OF INDIA) COMPANY ADDRESS DETAILS FOR THE YEAR 2020 DEALER IN TOBACCO Apllication phone/Mobile S.No. Company Address of the company (Regd.office) Email-id Regn.No. Type No "ALLIED HOUSE" DOOR NO.10-2-26 2ND LANE, SAMBASIVAPET 1 ALLIED AGRO TRADERS RENEW [email protected] 9866146097 TB/DEALER/2020/07 GUNTUR,GUNTUR DISTRICT,ANDHRA PRADESH,522001 ANNAPURNA TOBACCO OPPOSITE OLD APF.NO.24 TOBACCO BOARD TANGUTURU ,PRAKASAM 2 RENEW [email protected] 9949114692 TB/DEALER/2020/19 COMPANY DISTRICT,ANDHRA PRADESH,523274 DOOR NO:13-7-13 6TH LINE , GUNTURIVARI THOTA GUNTUR,GUNTUR 3 ARAVIND ENTERPRISES RENEW [email protected] 9246485697 TB/DEALER/2020/21 DISTRICT,ANDHRA PRADESH,522001 ASHOK KUMAR CLOTH BAZAAR CHOWTRA CENTER GUNTUR ,GUNTUR DISTRICT,ANDHRA 4 RENEW [email protected] 9849093201 TB/DEALER/2020/25 GOUTHAMCHAND PRADESH,522003 A.S. KRISHNA & CO. PVT. TOBACCO COLONY P.B.NO.62 GT ROAD,(NORTH) MANGALAGIRI ROAD 5 RENEW [email protected] 9866432509 TB/DEALER/2020/29 LTD. TOBACCO COLONY GUNTUR,GUNTUR DISTRICT,ANDHRA PRADESH,522001 6 A.VENKATESWARA RAO RENEW AMARAVATHI,GUNTUR DISTRICT,ANDHRA PRADESH,522020 [email protected] 9394153154 TB/DEALER/2020/30 ONGOLE ROAD M.NIDAMANURU TANGUTUR MANDAL,PRAKASAM 7 SURYA ENTERPRISES RENEW [email protected] 9440853810 TB/DEALER/2020/42 DISTRICT,ANDHRA PRADESH,523279 CHANDANMAL DOOR NO:21-13-58 NUNEVARI STREET CHOWTRA GUNTUR,GUNTUR 8 RENEW [email protected] 9440441966 TB/DEALER/2020/45 -

Download Full Report

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Local Bodies for the year ended March 2014 Government of Andhra Pradesh Report No. 5 of 2015 www.cag.gov.in Reference to Paragraph Page iii v About this Report 1 v Background 2 v Organisational set-up 3 v Significant Audit Observations 4 vii ͷǦ Finances of Local Bodies 1.1 1 Devolution of Funds and Functions 1.2 3 Accounting Arrangements 1.3 3 Audit Mandate 1.4 4 Financial Reporting 1.5 6 Conclusion 1.6 9 Ǧ 2 11 Ǧ 3.1 35 ǣ ǡ 3.2 45 3.3 56 3.4 57 3.5 58 ǯ ȋ Ȍ Appendix Reference to Subject No. Paragraph Page 1 Statement showing roles and responsibilities of each level of organisational set-up of Panchayat Raj Overview 61 Institutions 1.1 Statement showing district wise and department wise devolution of funds to PRIs during 2012-13 and 1.2 63 2013-14 1.2 Statement showing the details of non-compilation of 1.5.7 63 Accounts in ULBs 3.1 Details of Audit Sample 3.1.2 66 3.2 Audit findings relating to assessments of test- 3.2.3 67 checked properties 3.3 Audit findings relating to collection of property tax 3.2.4.1 68 in test-checked properties 3.4 Statement showing the details of contributions recovered towards Provident Fund, but not remitted 3.5 69 to Fund Commissioner Glossary of abbreviations 71 This Report pertaining to the erstwhile composite state of Andhra Pradesh for the year ended March 2014 has been prepared for submission to Governors of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana under Article 151 of the Constitution of India, and in accordance with Section 45(1) of the Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act, 2014.