Plumage Colour Variations in the Agapornis Genus: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shells and Ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: Indications for Modern Behavior

Journal of Human Evolution 56 (2009) 307–314 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer a,*, Bernard Vandermeersch b, Ofer Bar-Yosef c a The Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies and Department of Maritime Civilizations, University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel b Laboratoire d’Anthropologie des Populations du Passe´, Universite´ Bordeaux 1, Bordeaux, France c Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA 02138, USA article info abstract Article history: Qafzeh Cave, the burial grounds of several anatomically modern humans, producers of Mousterian Received 7 March 2008 industry, yielded archaeological evidence reflecting their modern behavior. Dated to 92 ka BP, the lower Accepted 15 October 2008 layers at the site contained a series of hearths, several human graves, flint artifacts, animal bones, a collection of sea shells, lumps of red ochre, and an incised cortical flake. The marine shells were Keywords: recovered from layers earlier than most of the graves except for one burial. The shells were collected and Shell beads brought from the Mediterranean Sea shore some 35 km away, and are complete Glycymeris bivalves, Modern humans naturally perforated. Several valves bear traces of having been strung, and a few had ochre stains on Glycymeris insubrica them. Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction and electron spin resonance (ESR) readings that placed both the Skhul and Qafzeh hominins in the range of 130–90 ka BP (Schwarcz Until a few years ago it was assumed that seashells were et al., 1988; Valladas et al., 1988; Mercier et al., 1993). -

Northern Rivers Feral Deer Identification Guide

Northern Rivers Feral Deer Identification Guide Menil (spotted) Fallow Buck, Western Sydney Parklands. Fallow Deer (Dama dama) Chital Deer (Axis axis) Introduction and distribution Introduction and distribution Fallow Deer were introduced to Tasmania in the 1830’s Chital Deer were introduced to Australia from India and mainland Australia around the 1880’s from Europe. in the 1860s. Wild populations of Chital exist in Fallow deer are the most widespread and established Queensland near Charters Towers, with other smaller of the feral deer species in Australia. They occur in isolated population in NSW, South Australia and Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and Victoria. Range and densities are increasing from South Australia. isolated pockets and deliberate release for hunting. Habitat and herding Habitat and herding The Fallow Deer are a herd deer inhabiting semi-open Chital deer are herbivores that browse on a variety of scrubland and frequent and graze on pasture that grasses, fruit and leaves. They are gregarious and can is in close proximity to cover. They breed during the form groups of more than 100 individuals. They do April/May, fawns are born in December and the bucks not have a defined breeding season, and are capable cast their antlers in October. Antlers are regrown by of producing three offspring in two years. Chital deer February. In rut, the buck makes an unmistakable will eat their shed antlers if their diet is lacking the croak, similar to a grunting pig. The calls vary from vitamins and minerals. Females will separate from the high pitched bleating to deep grunts. -

Dynamics and Determinants of Land Change in India: Integrating Satellite Data with Village Socioeconomics

Reg Environ Change DOI 10.1007/s10113-016-1068-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dynamics and determinants of land change in India: integrating satellite data with village socioeconomics 1 2 3 2 Prasanth Meiyappan • Parth S. Roy • Yeshu Sharma • Reshma M. Ramachandran • 4 5 1 Pawan K. Joshi • Ruth S. DeFries • Atul K. Jain Received: 11 April 2016 / Accepted: 12 October 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract We examine the dynamics and spatial determi- *23,810 km2 (1985–1995) to *25,770 km2 (1995–2005). nants of land change in India by integrating decadal land The gross forest gain also increased from *6000 km2 cover maps (1985–1995–2005) from a wall-to-wall analy- (1985–1995) to *7440 km2 (1995–2005). Overall, India sis of Landsat images with spatiotemporal socioeconomic experienced a net decline in forest by *18,000 km2 (gross database for *630,000 villages in India. We reinforce our loss–gross gain) consistently during both decades. We results through collective evidence from synthesis of 102 show that the major source of forest loss was cropland case studies that incorporate field knowledge of the causes expansion in areas of low cropland productivity (due to soil of land change in India. We focus on cropland–fallow land degradation and lack of irrigation), followed by industrial conversions, and forest area changes (excludes non-forest development and mining/quarrying activities, and exces- tree categories including commercial plantations). We sive economic dependence of villages on forest resources. show that cropland to fallow conversions are prominently associated with lack of irrigation and capital, male agri- Keywords Land use change Á Drivers Á Causes Á cultural labor shortage, and fragmentation of land holdings. -

Natural Solutions

Natural Solutions Natural Solutions Introduction Table of Contents Graham is the nation’s fastest growing provider of The species featured on these pages are the ones architectural wood doors. In addition to offering most often used for architectural flush wood doors. you a wide selection of flush doors (including fire However, there are thousands of wood species that rated, acoustical, pairs, decorative, dutch, wicket, can also be used for your Graham wood doors. A and transoms) and accessories (such as lites, applied few of these species are Anigre, Bamboo, Makore, moulding, and machining), we have an entire team Rosewood, Sapele, Wenge, and Zebrawood. Contact of individuals that are here for one purpose... your Graham Customer Service Professional to learn to serve you. more. Graham wood doors meet or exceed WDMA and Cherry AWS performance criteria. We offer doors with 20, Plain Sliced .................................................. 2, 3 45, 60, and 90 minute fire ratings and acoustical Mahogany doors with STC ratings from 27 to 46. Additionally, Flat Cut ......................................................... 4, 5 Graham wood doors can contribute to “green Black Walnut building” with recycled content, regional materials, Plain Sliced ...................................................6, 7 rapidly renewable materials, FSC certified wood, Maple and/or no added urea-formaldehyde. Plain Sliced White ......................................8, 9 Oak Everyone at Graham is proud of the beauty Plain Sliced Red .....................................10, 11 exemplified in each and every door we make. Wood Plain Sliced White .................................12, 13 is an aesthetically appealing material, stimulating the Rift Red ......................................................14,15 senses of sight, touch, and smell. The appearance of Rotary Red ................................................16,17 wood is influenced by a number of factors controlled Birch by nature. -

Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology, and Biochemistry: Unit

U. S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice Sourcebook in Forensic Serology, Immunology, and Biochemistry Unit M:Banslations of Selected Contributions to the Original Literature of Medicolegal Examinations of Blood and Body Fluids - a publication of the National Institute of Justice About the National Institute of Justice The National lnstitute of Justice is a research branch of the U.S. Department of Justice. The Institute's mission is to develop knowledge about crime. its causes and control. Priority is given to policy-relevant research that can yield approaches and information State and local agencies can use in preventing and reducing crime. Established in 1979 by the Justice System Improvement Act. NIJ builds upon the foundation laid by the former National lnstitute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice. the first major Federal research program on crime and justice. Carrying out the mandate assigned by Congress. the National lnstitute of Justice: Sponsors research and development to improve and strengthen the criminal justice system and related civil justice aspects, with a balanced program of basic and applied research. Evaluates the effectiveness of federally funded justice improvement programs and identifies programs that promise to be successful if continued or repeated. Tests and demonstrates new and improved approaches to strengthen the justice system, and recommends actions that can be taken by Federal. State. and local governments and private organbations and individuals to achieve this goal. Disseminates information from research. demonstrations, evaluations. and special prograrris to Federal. State. and local governments: and serves as an international clearinghouse of justice information. Trains criminal justice practitioners in research and evaluation findings. -

INDIGENOUS AGROFORESTRY in the PERUVIAN AMAZON: BORA INDIAN Managementr of SNIDDEN FALLOWS WILLIAM M

INDIGENOUS AGROFORESTRY IN THE PERUVIAN AMAZON: BORA INDIAN MANAGEMENTr OF SNIDDEN FALLOWS WILLIAM M. DENEVAN, JOIN M. TREACY, JANIS B. ALCORN CHRISTINE JULIE DENSLOW PADOCH, and SALVADOR FLORES PAITAN n recent years students nagement of tropical forest of Amazonia resurces: 1. farmers, but have ema- the diverse, multistoried rarely among colonist phasized swidden (shift- farmers. that some of ing cultivation However, it has received little at. the most successful food field) which protects the tention; producing adap- soil and allows brief mentions include: Denevan tations to the rain forest for habitat recovery (1971: habitat have under long fallow 508-509) for the Campa in been those of the (e.g., Conklin, 1957; eastern indigenous tribes, and Harris, Peru; Pose', 1982; 1983: 244. that consequently 1971); 2. the house g:arden, or we have much to learn dooryard 245) for the Kayap6 in central from these garden, also diverse and mul- Brazil, "ecosystem" people. "Refined Basso (1973: 34-35) for the Kalapalo over tistoried, but with :) large complement in millennia, Amazon Indian agri- of central Brazil; Eden (1980) culture tree crops ind with soil additives for the preserves the soils and from Andoke and Witoto the househoid retise, ash, and in the Colombian ecosystem ... If manure (e.g., Amazon; Smole the knowledge of in- Covich and (1976: 152-156) and digenous peoples can Nic-tcrson, 1966); and 3. the for he integrated with planting, protection, Harris (1971: 4S7, 489) and To. modern technological know-how, and harvesting of rres Espinoza then a trail side and campsite (19 0) for the Shuar new path for ecologically vegetation ("no- in eastern sound develop- medic aQricullrc"' Ecuador. -

Seasonal Cultivated and Fallow Cropland Mapping Using MODIS- Based Automated Cropland Classification Algorithm

Seasonal cultivated and fallow cropland mapping using MODIS- based automated cropland classification algorithm Zhuoting Wu Prasad S. Thenkabail Rick Mueller Audra Zakzeski Forrest Melton Lee Johnson Carolyn Rosevelt John Dwyer Jeanine Jones James P. Verdin Downloaded From: http://remotesensing.spiedigitallibrary.org/ on 11/19/2015 Terms of Use: http://spiedigitallibrary.org/ss/TermsOfUse.aspx Seasonal cultivated and fallow cropland mapping using MODIS-based automated cropland classification algorithm Zhuoting Wu,a,b Prasad S. Thenkabail,a Rick Mueller,c Audra Zakzeski,c Forrest Melton,d,e Lee Johnson,d,e Carolyn Rosevelt,d John Dwyer,f Jeanine Jones,g and James P. Verdinf aUSGS Western Geographic Science Center, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 [email protected] bNorthern Arizona University, Merriam-Powell Center for Environmental Research, Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 cUSDA NASS, Fairfax, Virginia 22030 dCSU Monterey Bay, Seaside, California 93955 eNASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California 94035 fUSGS EROS Data Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota 57198 gCalifornia Department of Water Resources, Sacramento, California 94236 Abstract. Increasing drought occurrences and growing populations demand accurate, routine, and consistent cultivated and fallow cropland products to enable water and food security analy- sis. The overarching goal of this research was to develop and test automated cropland classi- fication algorithm (ACCA) that provide accurate, consistent, and repeatable information on seasonal cultivated as well as seasonal fallow cropland extents and areas based on the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer remote sensing data. Seasonal ACCA develop- ment process involves writing series of iterative decision tree codes to separate cultivated and fallow croplands from noncroplands, aiming to accurately mirror reliable reference data sources. -

The Rice Agroecosystem, Cuban Fulvous Whistling Ducks and Avian Conservation

THE RICE AGROECOSYSTEM, CUBAN FULVOUS WHISTLING DUCKS AND AVIAN CONSERVATION Lourdes Mugica Valdes Lic., Universidad de la Habana 1 981 r THESIS SUBMllTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCES in the Department of Biological Sciences O Lourdes Mugica Valdes 1993 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY October 1993 All rights resewed. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: LOURDES MUGICA-VALDES Degree: Master of Science f Title of Thesis: THE RICE AGROECOSYSTEM, CUBAN FULVOUS WHISTLING DUCKS, AND AVIAN CONSERVATION Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. N.H. Haunerland, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor, Departme Dr. N.Af ~er&k;fiofEssor, Depart ent of Biological Sciences, SFU Dr. Kee Bass, AssociaYe Piofebsor Department of Zoology, UBC External Examiner Date Approved 5-8 - /.9?3 . PART I AL COPYR 1 GHT L l CENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser Unlverslty the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay'(the ,ltle of whlch Is shown below) to users of the Slmh Frarer Unlversl ty ~lbr&~, and to make part la l or single coples only for such users or In response to a request from the 1 i brary of any other unlverslty, or other educat lona l I nst I tut Ion, on its own behalf or for one of Its users. I further agree that permission formultlple copying of thls work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studles. It is understood that copyrng or publlcatlon of thls work for flnanclal gain shall not be allowed without my written permlsslon. -

Environmentally Friendly Elmosoft Leather

LEATHER SEATING FABRIC Environmentally Friendly elmosoft Leather ELMOSOFT Prussian 77158 Prussian 77158 Dark Blue 77030 Royal 77026 Blue 07075 Elf 78023 Rain Forset 98015 Verdun 98047 Crusoe 88020 LaPalma 88005 Bilbao 88033 Navy 77127 Dark Navy 97038 Jungle 87088 Dark Slate 17027 Light Slate 07008 Burgundy 95006 Brown Bramble 93099 Brown 93129 Cocoa Brown 93101 Raw Umber 43083 Milk Chocolate 33001 Tan 33004 Peru Tan 53032 Rich Tan 54035 Flax 22030 Castro 75010 Blue Violet 57349 Red Violet 76025 Solid Pink 16003 Pearl Lusta 07080 Maroon 35126 Crimson 55002 Red 05011 Crimson Glory 05007 Orange Red 45018 Rust 45065 Persimmon 45050 Moon Yellow 44012 Sunshine 44026 Electric Yellow 44005 Black 99999 Gondola 91102 Gun Metal 71017 Shady Lady 11033 Parchment 11073 Dark Brown 93068 Shadow 13064 Dusty Grey 13048 Grey 11049 Light Grey 01037 Fawn 13087 Wet Sand 01003 Beige 13072 Fallow 12105 Sapling 01021 Light Brown 13053 Champagne 12080 Buttered Rum 43054 Equator 22024 Chamois 02085 Cherokee 02110 Taupe 01061 O White 01040 Snow 00100* Colonial 00118* Bianca 01085 Pale Pink 06001 Tranquil 07029 Mint 08035 Electric White 00109* * Call factory for availability. TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION Property Target Value Method LIGHTFASTNESS 6 ISO I05-B02 WET-RUBBING 80/4 ISO 11640 DRY-RUBBING 2000/4 ISO 11640 SWEAT-RUBBING 50/4 ISO 11640 FINISH-ADHESION 2 N/CM ISO 11644 TEAR-STRENGTH 20 N DIN 53329-A THICKNESS 1.1 - 1.3 MM Color assessment: Daylight source D 65, closely corresponding to CIE standard light D 65. LEATHER SEATING FABRIC TECHNICAL INFORMATION Elmosoft Chrome Free Leather Full top grain aniline dyed, semi-aniline leather Origin: Sweden. -

Just Ask AKC to Remove Non-‐Standard Colors

Just Ask AKC To Remove Non-Standard Colors - Cindy Stansell This article was originally printed in The Bulldogger March 2016 and is reprinted here with permission. This article may not be reprinted except with permission of the author. We have to understand the AKC registration system in order to make changes. How does the system work? What changes can be proposed and how would they be implemented? SELECTION OF COLOR ON REGISTRATION. Before the early 1990s the blue slips listed frequently used colors – generally, the standard colors. If an owner did not select one of the colors on the blue slip, AKC would send him an expanded list of colors used by AKC. The expanded list also contained a “fill-in-the-blank” line where the owner could list any color. Under this system any color could be listed and registered. In the early 1990s AKC decided to “standardize” colors and to eliminate the “fill-in-the- blank.” During this two-three year period AKC contacted every parent club. The purpose was to provide a list of colors that had been registered to date and give the parent clubs an opportunity to designate which colors should be listed as standard and which should be listed as “alternate.” The BCA responded and listed the following colors as “alternate”: • Black & White • Black, Fawn & White • Gray & White • Bronze • Black, Red & White • Black • Gray • Black and Fawn Please remember that at this time the BCA Executive Council was not aware of anyone purposely breeding non-standard colors. Occasionally a Bulldog was produced with a non- standard color, but this was not intentionally done nor was it a normal occurrence. -

Deer Identification Guide

Record your data with Notes on Antlers Antlers are an outgrowth of the skeletal system of deer and are Deer Identification grown and shed annually by males. Initiation of antler development, Deer Scan subsequent growth and eventually shedding are regulated by testosterone. During growth the antlers are covered in a sensitive DeerScan (a component of FeralScan), is a free community skin coated with hair, known as velvet. As the antler approaches full resource for recording sightings of feral deer, reporting the damage development, blood flow to the velvet is restricted and it dries and they cause, and documenting control actions you undertake. Guide flakes. During this time deer may rub off the velvet by thrashing the https://www.deerscan.org.au vegetation, resulting in a clean or polished set of antlers. How to get started The size, shape and arrangement of tines on antlers can be used to identify a species. However, it can take several years of successive 1. Register your details growth for an animal to produce full antlers that are suitable to identify the species. The first set of antlers a male grows are usually unbranched Register your details in DeerScan or simply record information with and called spikers. a valid email address. You do not need to register but it will make it easier for you to view your own data, and enable the FeralScan Yearly antler development of team to contact you about deer information in your local area. Sambar Deer 2. Map your observations Record wherever you see deer, what species you have seen, what problems they have caused, and control activities such as ground Source: Frank Knight, Field Identification guide for the Australian Alps shooting. -

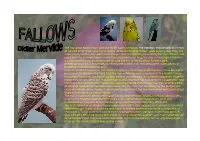

The Mutation Fallow Have at Least Three Types of Fallow, the GERMAN

The mutation Fallow have at least three types of Fallow, the GERMAN, ENGLISH AND SCOTTISH, all named after their country of origin, although none of these types is common. They are superficially similar, but adult birds may be distinguished by examining the eye. All have red eyes, but the German Fallow shows the usual white iris ring, the eye of the English Fallow is a solid red with a barely discernible iris and the iris of the Scottish Fallow is pink. Breeding Fallows is a challenge, not everyone is able to do this because it takes years of breeding to obtain a better bird. In an attempt to regularise the names of mutations across all psittacines, it has been pro- posed by Inte Onsman (MUTAVI) that the name Pale Fallow be adopted for the English Fallow mutation. The name Dun Fallow has also been proposed, and Terry Martin suggests Beige Fal- low or Grey-Brown Fallow. But in Budgerigar clubs they have not followed that suggestion and they kept the name English Fallow. The same happened with the German Fallow where Inte Onsman proposed the name Bronze Fallow but this was not accepted by the Budgerigar clubs worldwide. Why change it when everybody knows the meaning when we talked about English, German or Scottisch Fallow. The most common Fallows are English Fallows and German Fallows, Scottish Fallow is very near to the English Fallow and in 10 years of breeding Fallows I have never seen one. In appearance they are all very similar, only genetically are they very different. The first report of an English Fallow appeared in 1937 in the aviaries of F.Dervan (U.K.) In that time he bought a pair of Skyblues and a pair of Greens and intermated de youngsters of © DM these pairs.