Draft Environmental Impact Statement, CPDWS, Rio Grand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 OHV Grant Recommended Funding Approval

State Trails Program 13787 US Hwy. 85 N., Littleton, Colorado 80125 P 303.791.1957 | F 303.470-0782 May 6-7, 2020 2020-2021 OHV Trail Grant funding awards as recommended by the State Recreational Trails Committee. This letter is a summary and explanation of the enclosed Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) 2020-2021 OHV Trail Grant funding recommendations for Parks and Wildlife Commission (PWC) approval during the May 2020 meeting. We are requesting approval for 60 grants for a total award amount of $4,273,860. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The Colorado Parks and Wildlife Division’s (CPW) Trails Program, a statewide program within CPW, administers grants for trail-related projects on an annual basis. Local, county, and state governments, federal agencies, special recreation districts, and non-profit organizations with management responsibilities over public lands may apply for and are eligible to receive non- motorized and motorized trail grants. Colorado’s Off-highway Vehicle Trail Program CPW’s OHV Program is statutorily created in sections 33-14.5-101 through 33-14.5-113, Colorado Revised Statutes. The program is funded through the sale of OHV registrations and use permits. It is estimated that almost 200,000 OHVs were registered or permitted for use in Colorado during the 2019-2020 season. The price of an annual OHV registration or use- permit is $25.25. Funds are used to support the statewide OHV Program, the OHV Registration Program and OHV Trail Grant Program, including OHV law enforcement. The OHV Program seeks to improve and enhance motorized recreation opportunities in Colorado while promoting safe, responsible use of OHVs. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

Rocky Mountain Region Campground List

ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION COLORADO CAMPGROUND LIST ARAPAHO & ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FORESTS (970) 295.6700 This Campground List contains all the Forest Service campgrounds located within the BOULDER RD* - BOULDER, CO (303) 541.2500 Rocky Mountain Region. The campgrounds are listed by State, National SITE # OF MAX BASE CAMPGROUND NAME Forest/Grassland, and Ranger District. Base Minimum Camping Fees are listed, but ELEVATION SITES SPUR FEE we cannot show additional fees that may be applicable (hook-ups, etc.). Most Rocky Camp Dick 8,650' 41 40' $19 R* Y Y Mountain Region campgrounds are open from Memorial Day through Labor Day. To Kelly Dahl 8,600' 46 40' $19 R* Y N find a campground's Open/Closed status, contact the appropriate Ranger District office. Campground locations are shown on each National Forest or Meeker Park 8,600' 29 35' $11 FC* N N Grassland Visitor Information Map and they can be viewed online at: Olive Ridge 8,350' 56 40' $19 R* Y N http://www.fs.usda.gov/goto/r2/recreation/camping Pawnee 10,400' 47 40' $19 R* Y Y Peaceful Valley 8,500' 17 30' $19 R* Y Y Rainbow Lakes 10,000' 14 40' $13 FC* N Y FOR CAMPGROUND RESERVATIONS GO TO: RECREATION.GOV CANYON LAKES RD* - FORT COLLINS, CO (970) 295.6700 SITE # OF MAX BASE 1.877.444.6777 www.recreation.gov CAMPGROUND NAME ELEVATION SITES SPUR FEE Campgrounds accepting reservations are marked with *R under the column with the Ansel Watrous 5,800' 17 45' $19 R* Y Y Recreation.gov logo above. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2021 to 09/30/2021 Rio Grande National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2021 to 09/30/2021 Rio Grande National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, On Hold N/A N/A Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders 907-586-7886 EIS [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. R2 - Rocky Mountain Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Xcel Energy Transmission and - Special use management Developing Proposal Expected:03/2021 05/2021 Matthew Custer Distribution Authorization; Est. Scoping Start 12/2020 720-822-4321 Operation and Maintenance [email protected] Plan Project Description: The Forest Service proposes to reauthorize approximately 293 miles of existing electric transmission line and 196 CE miles of electric distribution line; develop and implement a standardized O&M Plan for routine maintenance and vegetation management. -

2019 OHV Trail Grants Funding Approval

congressional districts, one member appointed from the state at large and one member that represents the GOCO Board. The Committee also serves as Colorado’s State Recreational Trail Advisory Committee as required by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) to be eligible for RTP funds. To be in compliance with federal RTP funding eligibility rules, committee membership must include trail users and there must be representation of both off- road motorized recreational trail users and non-motorized recreational trail interests. The Committee oversees CPW’s annual trail grant application reviews, scoring and ranking processes and submits its recommendations for grant funding strategies to the Commission for their review, consideration and final approval. Appendix A lists the current Committee members. The 2018 OHV Grant Application and Review Process OHV grant applications are sent out by e-mail, ground mail, and are posted on the CPW’s Trails Program website each year. Trail grant opportunities are publicized annually through press releases, newsletters, the state website, and e-mail information networks. Technical assistance for grant preparation is provided by CPW Trails Program staff to potential applicants. The submission deadline for OHV grant applications is the first business day of December each year. The Commission, through its Policy A-104, has authorized a subcommittee structure to assist the Committee in formulating its grant recommendations. Subcommittee members are appointed to the Grant Review and Ranking Subcommittees for the purpose of reviewing and ranking grant applications and compiling funding recommendations for the Committee’s consideration. To solicit public comment, all grant applications are posted on the CPW Trails Program’s website and every public comment is evaluated as part of a subcommittee’s grant review and ranking process. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Rio Grande National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Rio Grande National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Rio Grande National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 01/01/2021 to 03/31/2021 Rio Grande National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Nancy Rusho 228, subpart A. Orders DEIS NOA in Federal Register 202-731-9196 09/13/2018 [email protected] EIS Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 11/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. These regulations apply to all NFS lands open to mineral entry under the US mining laws. More Information is available at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/science-technology/geology/minerals/locatable-minerals/current-revisions. R2 - Rocky Mountain Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) 01/01/2021 04:04 am MT Page 1 of 9 Rio Grande National Forest Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R2 - Rocky Mountain Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Xcel Energy Transmission and - Special use management Developing Proposal Expected:03/2021 05/2021 Matthew Custer Distribution Authorization; Est. -

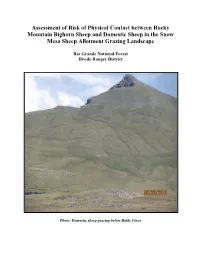

Assessment of Risk of Physical Contact Between Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep and Domestic Sheep in the Snow Mesa Sheep Allotment Grazing Landscape

Assessment of Risk of Physical Contact between Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep and Domestic Sheep in the Snow Mesa Sheep Allotment Grazing Landscape Rio Grande National Forest Divide Ranger District Photo: Domestic sheep grazing below Baldy Cinco TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT 4 Why the Concern Now 6 ALTERNATIVES EVALUATED 8 KEY CONCEPTS, GUIDANCE AND RECOMMENDATION DOCUMENTS 10 HISTORY OF DOMESTIC SHEEP GRAZING ON THE SNOW MESA LANDSCAPE 12 CENTRAL SAN JUAN BIGHORN SHEEP HERD 14 AFFECTED BIGHORN SHEEP HERDS S-22 San Luis Peak Sub-Herd 18 S-53 Bristol Head Sub-Herd 20 S-36 Bellows Creek Sub-Herd 22 RISK OF CONTACT TOOL 24 DISEASE HISTORY 27 RISK ASSESSMENT OUTCOMES 29 RISK OF CONTACT TOOL RESULTS 30 Snow Mesa Allotment Alternative 2 34 Snow Mesa Allotment Alternative 3 36 Table Allotment Alternative 2 38 Table Allotment Alternative 3 40 Miners Allotment Alternative 2 42 Miners Allotment Alternative 3 44 Ouray Allotment Alternative 2 46 Ouray Allotment Alternative 3 47 SUMMARY TABLE 49 DISCUSSION 50 UNCERTAINTIES 51 LITERATURE CITED 56 APPENDIX 1: RISK OF CONTACT TOOL RESULTS FOR ALTERNATIVE 2 58 APPENDIX 2: RISK OF CONTACT TOOL RESULTS FOR ALTERNATIVE 3 59 APPENDIX 3: RAM FORAY PROBABILITY FOR SUBGROUPS ALTERNATIVE 2 60 APPENDIX 4: RAM FORAY PROBABILTY CUMULATIVE FOR ALTERNATIVE 2 61 APPENDIX 5: RAM FORAY PROBABILITY FOR SUBGROUPS ALTERNATIVE 3 62 APPENDIX 6: RAM FORAY PROBABILTY CUMULATIVE FOR ALTERNATIVE 3 63 APPENDIX 7: PROJECT DESIGN CRITERIA 64 APPENDIX 8: RISK ASSESSMENT PROCESS – FOUR STEP OUTLINE 68 2 INTRODUCTION The Snow Mesa Landscape is located approximately 5 miles northwest of Creede, Colorado within Mineral and Hinsdale Counties within the Divide Ranger District of the Rio Grande National Forest. -

The Natural Heritage Network and Biodiversity

Biological Inventory of Rio Grande and Conejos Counties, Colorado Prepared for: The Nature Conservancy 1881 9th St., Suite 200 Boulder, CO 80302 Prepared by: Steve Kettler, Joe Rocchio, Robert Schorr, Julie Burt Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University College of Natural Resources 254 General Services Building Ft. Collins, Colorado 80523 March 31, 2000 Biological Inventory of Rio Grande and Conejos Counties, Colorado Prepared for: The Nature Conservancy 1881 9th St., Suite 200 Boulder, CO 80302 Prepared by: Steve Kettler, Joe Rocchio, Robert Schorr, Julie Burt Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University College of Natural Resources 254 General Services Building Ft. Collins, Colorado 80523 March 31, 2000 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS............................................................................................................................ VIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................. IX INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................................1 GENERAL STUDY AREA DESCRIPTION ..............................................................................................................2 METHODS .........................................................................................................................................................6 RESULTS..........................................................................................................................................................15 -

Eagle's View of San Juan Mountains

Eagle’s View of San Juan Mountains Aerial Photographs with Mountain Descriptions of the most attractive places of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains Wojtek Rychlik Ⓒ 2014 Wojtek Rychlik, Pikes Peak Photo Published by Mother's House Publishing 6180 Lehman, Suite 104 Colorado Springs CO 80918 719-266-0437 / 800-266-0999 [email protected] www.mothershousepublishing.com ISBN 978-1-61888-085-7 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Printed by Mother’s House Publishing, Colorado Springs, CO, U.S.A. Wojtek Rychlik www.PikesPeakPhoto.com Title page photo: Lizard Head and Sunshine Mountain southwest of Telluride. Front cover photo: Mount Sneffels and Yankee Boy Basin viewed from west. Acknowledgement 1. Aerial photography was made possible thanks to the courtesy of Jack Wojdyla, owner and pilot of Cessna 182S airplane. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Section NE: The Northeast, La Garita Mountains and Mountains East of Hwy 149 5 San Luis Peak 13 3. Section N: North San Juan Mountains; Northeast of Silverton & West of Lake City 21 Uncompahgre & Wetterhorn Peaks 24 Redcloud & Sunshine Peaks 35 Handies Peak 41 4. Section NW: The Northwest, Mount Sneffels and Lizard Head Wildernesses 59 Mount Sneffels 69 Wilson & El Diente Peaks, Mount Wilson 75 5. Section SW: The Southwest, Mountains West of Animas River and South of Ophir 93 6. Section S: South San Juan Mountains, between Animas and Piedra Rivers 108 Mount Eolus & North Eolus 126 Windom, Sunlight Peaks & Sunlight Spire 137 7. Section SE: The Southeast, Mountains East of Trout Creek and South of Rio Grande 165 9. -

Railroads of the San Luis Valley

New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 35th Field Conference. Rio Grande Rift: Northern New Mexico, 1984 297 RAILROADS OF THE SAN LUIS VALLEY ALLEN L. BOWMAN Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, New Mexico 87545 The Denver and Rio Grande Railway (D&RG) pushed its 3-foot- indebtedness of the Railway Company soon outstripped its earning gauge track over La Veta pass in the spring of 1877, reaching the new capacity. The first default on bond interest payments occurred in 1877 town of Alamosa on July 10, 1878 (Athearn, 1962). The isolated res- (Athearn, 1962). Another lucrative source of profit came from the idents of the San Luis Valley (Fig. 1) could now travel the 130 miles practice of creating new towns on the railroad, on land conveniently to Pueblo in eight hours, or 250 miles to Denver in only 14 hours owned by Palmer's group. These townsites were then sold as town lots (Anderson, 1963, p. 405). More significantly, the convenience of rail to businessmen wishing to benefit from the new railroad. If a town transportation quickly made Alamosa the business and mercantile center of the San Luis Valley, a position that it still holds today. The position of Alamosa at end-of-track also made it the terminus for stage lines and wagon freight to the mining districts of the San Juan Mountains, supplanting the previous terminal towns of Garland City (4 miles east of Fort Garland) and La Veta. The railroad moved on to Chama in 1880, to Durango in 1881, and to Silverton in 1882, but the growth of the San Luis Valley was sufficient to support Alamosa, while Garland City became a ghost town and La Veta became a small farm and ranch center (Athearn, 1962).