CHICAGO SKYWAY TOLL BRIDGE HAER No. IL-145

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago

METROPOLITAN WATER RECLAMATION DISTRICT OF GREATER CHICAGO ATTACHMENT 1 PUBLIC NOTICE In accordance with the requirements of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 40 CFR 403.8(f)(2)(viii), the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (District) herewith provides notification to the public of those industrial dischargers to its system which were determined to be in significant noncompliance of applicable Pretreatment Standards or Other Requirements during the period from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019. DISCHARGERS FOUND IN SIGNIFICANT NONCOMPLIANCE WITH APPLICABLE PRETREATMENT REGULATIONS The industrial users identified below were found to be in significant noncompliance with applicable Pretreatment Standards or Other Requirements in accordance with the selection criteria established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 40 CFR 403.8(f)(2)(viii), or additional selection criteria established by the District in Appendix E, Section 2, to the Sewage and Waste Control Ordinance, during the report period from January 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019. EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS ID NAME ADDRESS POLLUTANT Aallied Die Casting Co. of 3021 Cullerton Dr Fats, Oils, 10002 Illinois Franklin Park and Greases 4408 West Cermak Road 12749 Alanson Mfg Co. Zinc Chicago 14303 Paxton Avenue 13513 Ashland, LLC Toluene * Calumet City Automatic Anodizing 3340 West Newport Avenue 12238 Copper Corporation Chicago 5005 South Nagle Avenue Fats, Oils, 12302 Azteca Foods, Inc. Chicago and Greases Berkshire Investments, LLC 1601 South 54th Avenue 26039 Zinc * d/b/a Chicago Extruded Metals Cicero 1111 South Wheeling Road 11203 Block & Company Inc. Zinc Wheeling 14101 South Seeley Avenue 12988 Chicago Magnesium Casting Co. -

2018 Invest in Cook Grant Program

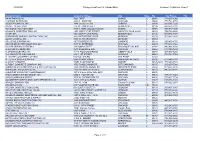

2018 INVEST IN COOK Toni Preckwinkle, President Cook County Board of Commissioners Martha Martinez, Chief Administrative Officer Bureau of Administration John Yonan, P.E., Superintendent Department of Transportation & Highways 2018 INVEST IN COOK AWARDS PROJECT NAME APPLICANT PROJECT TYPE PROJECT PHASE AWARDED 78th Avenue Reconstruction Bridgeview Freight Preliminary Engineering $350,000 Braga Drive Improvements Broadview Freight Construction $145,000 31st Street Corridor Multimodal Brookfield Roadway Preliminary Engineering $85,000 Impact Study Burnham Greenway Trail Bike/Ped Burnham Bike/Ped Preliminary Engineering $50,000 Bridge Over Five Rail Lines Dolton Road/State Street/Plummer Calumet City Freight Preliminary Engineering $200,000 Avenue Trucking Improvements Winchester Avenue Rehab Project Calumet Park Freight Design Engineering $172,000 Canal Street Viaduct Reconstruction – Adams Street to CDOT Transit Design Engineering $240,000 Madison Street Canal Street Viaduct Reconstruction – Taylor Street to CDOT Transit Design Engineering $300,000 Harrison Harrison Street Chicago Avenue Bus Transit Operations and Pedestrian Safety CDOT Transit Design Engineering $400,000 Improvements Howard Street Streetscape CDOT Roadway Construction $380,000 71st Street Streetscape CDOT Roadway Construction $500,000 79th Street Bus Transit Operations and Pedestrian Safety CDOT Transit Design Engineering $400,000 Improvements Major Taylor Trail – Dan Ryan Cook County Bike/Ped Preliminary Engineering $70,165 Woods Improvements Forest Preserve District -

MOVE-IN 2019 INSTRUCTIONS Stony Island Hall

MOVE-IN 2019 INSTRUCTIONS Stony Island Hall 5700 Stony Island Avenue Chicago, IL 60637 SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 21ST The residence hall doors will open at 9:00 AM for move-in. GETTING TO STONY ISLAND HALL FROM LAKE SHORE DRIVE Exit at 53rd Street Go west and drive under the Metra tracks Immediately after passing under the tracks, turn left onto South Lake Park Avenue Head south and proceed to 57th Street Turn left, driving back under the Metra tracks The Stony Island parking lot will be on your right hand side when you emerge from under the tracks Follow unloading instructions on page 2 FROM INDIANA Take the I-65 North or I-80 West to the Skyway (I-90/I-94 W) Drive westbound on the Skyway, exiting at Stony Island Avenue, exit 105 Drive north on Stony Island and turn left on 59th Street Immediately after passing under the Metra tracks, turn right onto South Harper Ave. Head north and proceed to 57th Street Turn right, driving back under the Metra tracks The Stony Island parking lot will be on your right hand side when you emerge from under the tracks Follow unloading instructions on page 2 FROM THE DAN RYAN EXPRESSWAY (I-94) Take exit 57 to Garfield Blvd/55th Street, and drive east, following the signs for 55th Street through Washington Park Once you cross South Cottage Grove Ave on 55th Street, the campus is on your right Continue along 55th Street until you reach South Lake Park Avenue and turn right Head south and proceed to 57th Street Turn left, driving under the Metra tracks The Stony Island parking lot will be on your right hand side when you emerge from under the tracks Follow unloading instructions below UNLOADING In order to facilitate a smooth and orderly flow into the building, cars will be lined up and students will be able to unload in the order in which they arrive. -

Leisure Pass Group Or Big Bus

All-Inclusive Guidebook Shedd Aquarium Attraction status as of Oct 2, 2020: Open Reservations required: book via Shedd Aquarium's website or by calling 312-939-2438. Please note: Shedd Aquarium is included exclusively on 1,2, 3, and 5-day All-Inclusive passes! It is not included in the Explorer pass or Build Your Own pass For an additional fee, you can also purchase tickets at the will-call ticket desk (pending availability) for a 4-D Experience. Shedd Aquarium is located on the Hop-On-Hop-Off-Bus Tour route at stop number 7: Shedd Aquarium, 1200 S. Lake Shore Drive. Hours of Operation We recommend visiting the Shedd Aquarium website for the most up-to-date information on hours of operation. Weekdays 9AM - 5PM Weekends and holidays 9AM - 6PM Closings & Holidays Thanksgiving and Christmas Day. Hours are subject to change without notice. Getting There Address On Chicago's Museum Campus 1200 S. Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605 US Hop-On Hop-Off Tour Stops Take CTA: Red, Orange, or Green Line to the Roosevelt Road/Museum Campus stop. Take CTA bus #146 from points north or south as well as from the Roosevelt Road "L" stop. Closest Bus Stop Take CTA: Red, Orange, or Green Line to the Roosevelt Road/Museum Campus stop. Take CTA bus #146 from points north or south as well as from the Roosevelt Road "L" stop. 360 CHICAGO Attraction status as of Oct 2, 2020: Open Getting In: To skip the ticketing line, look for the Go Chicago pass signage in the admissions area and present your pass for validation. -

CDOT (312) 744-0707 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 5, 2014 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] Pete Scales, CDOT (312) 744-0707 [email protected] MAYOR EMANUEL ANNOUNCES CITY REACHES HALFWAY POINT OF 100-MILE GOAL FOR PROTECTED BIKE LANES BY 2015 Next 20 Miles Installed This Spring; 30 More Miles in Design Phase Mayor Rahm Emanuel today announced the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) is halfway finished with the plan to install 100 miles of protected bike lanes by 2015, and is on track to achieve that milestone by early next year. “Improving our bicycling facilities is critical to creating the quality of life in Chicago that attracts businesses and families to the city,” Mayor Emanuel said. “We are making Chicago the most bike-friendly city in the United States.” Twenty more miles of protected bike lanes will be installed this spring and summer, with the remaining 30 miles in design phase and planned for installation later this year and early 2015. In 2013, CDOT installed 31 miles of new or restriped facilities, including 19 miles of protected bike lanes, bringing the number of protected bike lanes installed in Chicago since Mayor Emanuel came into office in May 2011 to 49 miles. Chicago’s bikeways now total more than 207 miles, according to CDOT’s report, 2013 Bikeways – Year In Review, which was released today. “Chicago is a national leader in building new and improved cycling facilities and setting a new standard for other cities to follow,” said CDOT Commissioner Rebekah Scheinfeld. “We are looking forward to continuing our bikeways construction efforts this summer to make Chicago the best cycling city in America.” Bikeways achievements in 2013 include: • Chicago’s first Neighborhood Greenway on Berteau Avenue • Bicycle-friendly treatments on three bridges • Installation of 12 bike corrals • 35,000 cyclists counted in monthly biking data collection events • Installation of 300 Divvy bike-share stations In addition to installing new lanes, maintenance of existing facilities continued as well. -

Non-Exempt Modification September 9, 2010

Non-Exempt Modification September 9, 2010 Non-Exempt Modification Pre-Revision Post-Revision Change in Project: Action Federal Funds Federal Funds Federal Funds Percentage Change (000) (000) (000) 01-10-0029 Chicago Department of Transportation Modification $2000 $2000 $ 0 0% FAU 1453 FAU 1454 Cermak Road FROM Ashland Avenue (COOK/Chicago) TO Martin Luther King, Jr Drive (COOK/Chicago) Completion Year Before Revision: 2012 Completion Year After Revision: 2012 Project Work Types Before Revision: SIGNALS - INTERCONNECTS AND TIMING Project Work Types After Revision: SIGNALS - INTERCONNECTS AND TIMING Financial Data Before Fund Source Project Phase FFY Total Cost Federal Cost Segment Revision STP-L CONSTRUCTION 11 2500 2000 Financial Data After Revision Fund Source Project Phase FFY Total Cost Federal Cost Segment STP-L CONSTRUCTION 11 2500 2000 Pre-Revision Post-Revision Change in Project: Action Federal Funds Federal Funds Federal Funds Percentage Change (000) (000) (000) 04-00-0022 IDOT District 1 Local Roads Modification $0 $0 $ 0 Before Revision: BALMORAL FROM BESSIE COLEMAN (COOK/CHICAGO) TO US 12 45 EAST OF MANNHEIM RD (COOK/ROSEMONT) After Revision: BALMORAL FROM BESSIE COLEMAN (COOK) TO US 12 45 EAST OF MANNHEIM RD (COOK) Completion Year Before Revision: 2015 Completion Year After Revision: 2015 Project Work Types Before Revision: HIGHWAY/ROAD - EXTEND ROAD INTERCHANGE - NEW BRIDGE/STRUCTURE - NEW Project Work Types After Revision: HIGHWAY/ROAD - EXTEND ROAD INTERCHANGE - NEW BRIDGE/STRUCTURE - NEW Financial Data Before Fund Source -

Residential Hotels in Chicago, 1880-1930

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. __x_____ New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Residential Hotels in Chicago, 1880-1930 B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Evolution of the Residential Hotel in Chicago as a Distinct Building Type (1880-1930) C. Form Prepared by: name/title: Emily Ramsey, Lara Ramsey, w/Terry Tatum organization: Ramsey Historic Consultants street & number: 1105 W. Chicago Avenue, Suite 201 city or town: Chicago state: IL zip code: 60642 e-mail: [email protected] telephone: 312-421-1295 date: 11/28/2016 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. _______________________________ _______________________________________________ Signature of certifying official Title Date _____________________________________ State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Licensed Contractor Report

3/23/2020 Chicago Department of Transportation Licensed_Contractors_Report Company Name Company Address City State Zip Day Phone Fax AA ANTHONYS INC 9621 TRIPP SKOKIE IL 60076 (773)230-1062 A ARROW SEWERAGE 4243 N. MONITOR CHICAGO IL 60634 (773)761-0759 ABBEY PAVING CO, INC. 1949 County Line Rd AURORA IL 60504 (630)585-7220 ABBOTT INDUSTRIES 225 WILLIAM STREET BENSENVILLE IL 60106 (630)595-2320 ACE CONSTRUCTION CORP 7334 N. MONTICELLO AVENUE SKOKIE IL 60076 (847)679-4155 ACHILLES CONSTRUCTION, INC. 4857 WEST 171ST STREET COUNTRY CLUB HILLS IL 60478 (708)799-0525 ACURA INC 556 COUNTY LINE ROAD BENSENVILLE IL 60106 (630)766-9979 ADAMSON PLUMBING CONTRACTORS, INC. 860 SOUTH FIENE DRIVE ADDISON IL 60101 (312)492-7600 ADEN PLUMBING INC 3804 W PRETSWICK ST MCHENRY IL 60050 ADJUSTABLE FORMS INC 1 E PROGRESS RD LOMBARD IL 60148 (630)953-8700 ADVANCED WATER SOLUTIONS LLC 7637 W. PETERSON CHICAGO IL 60631 (773)636-0066 A & H PLUMBING & HEATING 330 BOND STREET ELK GROVE VILLAGE IL 60007 (847)981-8800 ALARCON PLUMBING INC 8518 S KEDVALE AVE CHICAGO IL 60652 (773)349-1264 ALDRIDGE ELECTRIC INC 844 E. ROCKLAND ROAD LIBERTYVILLE IL 60048 (847)680-5200 ALL CONCRETE CHICAGO INC 414 E 1ST STREET HINSDALE IL 60521 (773)729-7004 ALLSTATE CONCRETE CUTTING 514 ROLLINS RD INGLESIDE IL 60041 ALL STATE SEWER & WATER 6941 W MONTROSE HARWOOD HEIGHTS IL 60706 (312)446-7300 ALMIGHTY ROOTER 16858 S LATHROP #1 HARVEY IL 60426-6031 (773)284-6616 ALRIGHT CONCRETE COMPANY INC. 1500 RAMBLEWOOD DR. STREAMWOOD IL 60107 (630)250-7088 AMERICAN BACKHOE SERVICE & EXCAVATING CO 2560 FEDERAL SIGNAL DR UNIVERSITY PARK IL 60484 (815)469-2100 AMERICAN LANDSCAPING, INC 2233 PALMER DR. -

Visitor Information Guide Department of Zoology, Division of Insects the Field Museum 2011

Visiting the Division of Insects at The Field Museum Visitor Information Guide Department of Zoology, Division of Insects The Field Museum 2011 Visitor Information Guide Visiting the Insect Collection Visiting the Insect Collection The Division of Insects collection of research specimens and library are used by scientists, graduate students and others from around the world. On average we host around 50 research visitors annually. The collection is primarily used for basic research on insects, arachnids, and myriapods. The collection and library are not open to the general public or used for activities that might disrupt scientific users. Due to reductions in our staff size, we cannot accommodate unannounced visitors. All visitors are requested to arrange visits at least one week in advance by contacting the staff member in charge of the collection of interest: • Coleoptera - Margaret Thayer, Division Head, Associate Curator, [email protected], (312) 665-7741 • Arachnida and Myriapoda - Petra Sierwald, Associate Curator, [email protected], (312) 665-7744 • Formicidae - Corrie Saux Moreau, Assistant Curator, [email protected], (312) 665-7743 • All other collections - Jim Boone, Assistant Collection Manager, [email protected], (312) 665-7745. The Division of Insects is open 8:30 a.m. – 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday. Arrangements to arrive earlier or to work later must be made in advance. The collection is not staffed and thus not open on weekends and federal holidays. Long term visitors can discuss the possibility for after hours and weekend access with their host. We ask that you confirm your visit date(s) with Divisional Staff before your arrival. -

Chicago Arts + Industry Commonsave (CAIC)K Nort Avenue N West Fullerton V

Chicago Arts + Industry Chicago,Commons IL N Table of Contents p03 Slide Deck p13 The Narrative 2 N Slide Deck 3 Kenwood Gardens Kenwood St. Laurence School Stony Island Arts Bank Garfield Park Industrial Arts ard e u n e v A h t ianapolis Boulev 5 Ind B e v A h t u o S levard apolis Bou treet Indian East 112th Street et outh S re t ast 108th S E e v A g n i w E h t u o S S ast 87th 87th ast Ave E South Avenue L Ewing South South Lake Shore Drive O e u n e v A h t u o treet S Ewing hore Dr hore ve S A outh Lake outh S South South Mackinaw Avenue 06th Street t 100th S hore Dr ve A S as st 1 South Buffalo Avenue E South Burley Avenue Ea South Harbor South t South Lake South South Shore Drive reet 1st Street h St East 93rd S ast 9 South Commercial Ave E East 95t al Ave al South Exchange Avenue ci East 92nd Street er Comm h h Sout Shore Drive t S South Muskegon 76th Ave East ny Avenue South Southt ho S venue Ant ast 75th ast A E uth ast 104th St hange So E East 83rd Street South Torrence Avenue South Exc South Colfax Ave treet d r a v e e l u t o a B Y h t u s o S South South Shore Drive tte arque t t M Dr S ue 100th ast Eas E rd S East 93 outh Anthony Aven e S riv an D es Dr y South V Ha ette South Jeffery Boulevard Vlissingen Rd st st qu a East 103rd Street E ar M nue e ast E East 76th Street ago Av East 87th Street ayes r D South Lake st H Shore Dr South Hyde Park Boulevard Ea outh South Chic t South Cornell Avenue S South Stony Island Avenue South Stony Island Ave ast 55th S South Stony Island Avenue treet E t S East 47th 47th East ast -

Opt-In Vendors and Cook County Commissioner Districts, 2014

Opt-InParticipating Vendors an Currencyd Cook CExchangeounty C Locationsommissio Collectingner Distr Useicts ,Tax 20 14 Opt-In Vendorson a nNon-Retailerd Cook Cou Transfernty Com ofm Motorission Vehicleser Districts, 2014 14 53 53 14 290 294 290 294 15 15 90 94 90 13 94 290 13 290 L 9 A L K A 9 E 190 K E M 190 10 12 I M 10 C I 12 H C I H 8 G 90 I A l Participating Locations 8 G 294 90 N 1 A 294 290 N Cook County 1 290 290 94 Commissioner Districts 88 290 94 (based on 2010 Census) 88 16 55 94 16 755 94 7 3 2 90 3 55 2 90 55 11 11 94 17 94 17 4 355 4 355 57 5 57 5 94 94 80 6 80 6 80 80 Map prepared by Cook County Department of Geographic Information Systems, 394 Bureau of Technology. Any attempt to repackage, resell or distribute this map without the 394 written permission of the Cook County Board of Commissioners is prohibited. 0 2 4 8 Miles 0 2 4 8 Miles Map prepared on Oct. 16, 2014; Department of Geographic Information Systems, Cook County Bureau of Technology; cook_vendor_2014.pdf; M©a 2p0 p1r4e pCaoroekd Cono uOnctyt. G16o,v 2e0rn1m4;e Dntepartment of Geographic Information Systems, Cook County Bureau of Technology; cook_vendor_2014.pdf; ©Yo 2u0 a14re C nooot kp Ceromuinttteyd G tov reerpnamceknatge, resell, or distribute this map without the written permission of the Cook County Board of Commissioners You are not permitted to repackage, resell, or distribute this map without the written permission of the Cook County Board of Commissioners PARTICIPATING CURRENCY EXCHANGE ADDRESS CITY & STATE ZIP PHONE FAX PARTICIPATING CURRENCY EXCHANGE ADDRESS CITY & STATE ZIP PHONE FAX 103rd & Halsted Currency Exchange Inc 801 W.