Homes for Londoners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Owen Hatherley El Gobierno De Londres 93 Shaohua Zhan La Cuestión De La Tierra En China 131

NEW LEFT REVIEW 122 SEGUNDA ÉPOCA mayo - junio 2020 PANDEMIA Mike Davis Entra en escena el monstruo 11 Ai Xiaoming Diario de Wuhan 20 Marco D’Eramo La epidemia del filósofo 28 N. R. Musahar Medidas de inanición en la India 34 Rohana Kuddus Limoncillo y plegarias 42 Mario Sergio Conti Pandemonio en Brasil 50 Vira Ameli Sanciones y enfermedad 57 R. Taggart Murphy Oriente y Occidente 67 ARTÍCULOS Michael Denning El impeachment como forma social 75 Owen Hatherley El gobierno de Londres 93 Shaohua Zhan La cuestión de la tierra en China 131 CRÍTICA Chris Bickerton La persistencia de Europa 153 Terry Eagleton Ciudadanos de Babel 161 Lola Seaton ¿Ficciones reales? 168 John Merrick Dorando la Gran Bretaña de 182 posguerra WWW.NEWLEFTREVIEW.ES © New Left Review Ltd., 2000 Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) INSTITUTO tds DEMOCRACIA SUSCRÍBETE owen hatherley EL GOBIERNO DE LONDRES ondres es probablemente la capital más descollante, en relación con el país que gobierna, entre los grandes Estados. En cierto sentido, siempre ha sido así: la sede del poder político en Westminster y el centro financiero de la City se Lestablecieron allí desde la Edad Media. Tuvo que hacer frente al desafío que supuso, hasta cierto punto, la aparición de grandes conurbaciones fabriles en las Midlands y el norte de Inglaterra, en Escocia y en el sur de Gales desde principios del siglo xix, pero el eclipse del poder industrial británico desde la Segunda Guerra Mundial ha reforzado la preemi- nencia de Londres. Los límites de la ciudad albergan casi 9 millones de habitantes, un récord histórico, sin incluir una enorme área metro- politana que abarca aproximadamente 14 millones de personas que trabajan en la capital, lo que supone alrededor de cinco veces el tamaño de sus rivales más cercanas en el Reino Unido (el Gran Manchester, Birmingham y Glasgow). -

97 APPENDIX A2a Comments On

APPENDIX A2a Comments on Lewisham Gateway Note: Comments in Italics refer to comments were made by visitors to the LPA Exhibition 88 Adelaide Avenue Concerned that the road system will not work and the scheme will worsen traffic. The objector also feels that the proposals to move the Quaggy and take away Charlottenburg Gardens will be detrimental to the environment. There must be other ways to improve the roundabout without damaging the area in a way that the proposed scheme will inevitably do. 6 Algernon Road He objects as the site is not suitable for the density of development proposed along with the traffic and pollution problems the development will caused. The plans are not in keeping with London policy in terms of treatment of rivers, care in proposing high rise solutions, loss of green space, alignment of development plans and transport capacity etc. A very low proportion of the housing units are to be made available as affordable housing and he questions the suitability of the site for hou sing. Also questions the business case for a mass of office space when there are large expanses of empty offices close by. The development is being driven by the developer’s business/profit model. The changes to the road system have not been proven to i mprove the situation and it is possible that the new arrangements would make the situation significantly worse. 107 Algernon Road The objector sees no proof that the proposed road system will work and fears that traffic will get worse, especially given all the other developments proposed. -

1891 United Kingdom Census - Persons from British Guiana

1891 United Kingdom Census - Persons from British Guiana Mar- District/ Last Name First Name Relation ital Age Occupation Place of Birth Head of Household Address Status H’hold Isabella (as Demerara, W. Emily EALES, College 1 Lansdown Villas, Queens Pde, ABEL Boarder - 16 Student 31/97 D.G. Ella) Indies Boarding House Cheltenham GLS ENG Margaret ABEL, Woodbine Villa, Beech Grove, Moffat ABEL William Son - 18 Scholar Demerara 05/13 Attorney's Wife DFS SCT Demerara, Henry ADAMS, 13 The Avenue, South Mimms MDX ADAMS Elsie M. Dau - 6 Scholar 8/233 British Guiana Wesleyan Minister ENG ADAMS Mary Head Wid 66 Private Means Demerara Self 10 Nelson St, Edinburgh MLN SCT 96/23 Demerara, Henry ADAMS, 13 The Avenue, South Mimms MDX ADAMS Mary E. Dau - 7 Scholar 8/233 British Guiana Wesleyan Minister ENG Emma MELHAM, Georgetown, ADAMSON Catherine Boarder Wid 38 Nurse Living on her own 2 Rose Cottages, Romford ESS ENG 11/103 Demerara means Josephine Harry (as AHRENS Boarder Unm 20 Commercial Clerk British Guiana D'OLIVEGIA, Living 7 Sproulston Rd, West Ham ESS ENG 74/160 Harey) on her own means Living on own Georgetown, AIRD Gertrude Head Mar 24 Self 13 St Pauls Rd, Hastings SSX ENG 18/210 means Demerara Labourer in Gas Georgetown, Richard TAGUE, 8 Lower Taff St, Merthyr Tydfil GLA ALEXANDER George Lodger Unm 20 29/133 Works Demerara General Huckster WLS Living on own British 42 Devonshire St, St Marylebone MDX ALLCARD Mary Head Wid 76 self 04/17 means Guayana ENG Self (wife Harriett ALLEN John Head Mar 43 Foreman Demerara 68 Bloomfield St, Hackney MDX ENG 17/85 ALLEN) Amelia Agnes Ambrose Demerara, 40 Adswood Lane West, Stockport CHS ALLISON Son Unm 16 - ALLISON (no 35/121 H.H. -

Who Is Council Housing For?

‘We thought it was Buckingham Palace’ ‘Homes for Heroes’ Cottage Estates Dover House Estate, Putney, LCC (1919) Cottage Estates Alfred and Ada Salter Wilson Grove Estate, Bermondsey Metropolitan Borough Council (1924) Tenements White City Estate, LCC (1938) Mixed Development Somerford Grove, Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Neighbourhood Units The Lansbury Estate, Poplar, LCC (1951) Post-War Flats Spa Green Estate, Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Berthold Lubetkin Post-War Flats Churchill Gardens Estate, City of Westminster (1951) Architectural Wars Alton East, Roehampton, LCC (1951) Alton West, Roehampton, LCC (1953) Multi-Storey Housing Dawson’s Heights, Southwark Borough Council (1972) Kate Macintosh The Small Estate Chinbrook Estate, Lewisham, LCC (1965) Low-Rise, High Density Lambeth Borough Council Central Hill (1974) Cressingham Gardens (1978) Camden Borough Council Low-Rise, High Density Branch Hill Estate (1978) Alexandra Road Estate (1979) Whittington Estate (1981) Goldsmith Street, Norwich City Council (2018) Passivhaus Mixed Communities ‘The key to successful communities is a good mix of people: tenants, leaseholders and freeholders. The Pepys Estate was a monolithic concentration of public housing and it makes sense to break that up a bit and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power.’ Pat Hayes, LB Lewisham, Director of Regeneration You have castrated communities. You have colonies of low income people, living in houses provided by the local authorities, and you have the higher income groups living in their own colonies. This segregation of the different income groups is a wholly evil thing, from a civilised point of view… We should try to introduce what was always the lovely feature of English and Welsh villages, where the doctor, the grocer, the butcher and the farm labourer all lived in the same street – the living tapestry of a mixed community. -

London's Housing Struggles Developer&Housing Association Dec 2014

LONDON’S HOUSING STRUGGLES 2005 - 2032 47 68 30 13 55 20 56 26 62 19 61 44 43 32 10 41 1 31 2 9 17 6 67 58 53 24 8 37 46 22 64 42 63 3 48 5 69 33 54 11 52 27 59 65 12 7 35 40 34 74 51 29 38 57 50 73 66 75 14 25 18 36 21 39 15 72 4 23 71 70 49 28 60 45 16 4 - Mardyke Estate 55 - Granville Road Estate 33 - New Era Estate 31 - Love Lane Estate 41 - Bemerton Estate 4 - Larner Road 66 - South Acton Estate 26 - Alma Road Estate 7 - Tavy Bridge estate 21 - Heathside & Lethbridge 17 - Canning Town & Custom 13 - Repton Court 29 - Wood Dene Estate 24 - Cotall Street 20 - Marlowe Road Estate 6 - Leys Estate 56 - Dollis Valley Estate 37 - Woodberry Down 32 - Wards Corner 43 - Andover Estate 70 - Deans Gardens Estate 30 - Highmead Estate 11 - Abbey Road Estates House 34 - Aylesbury Estate 8 - Goresbrook Village 58 - Cricklewood Brent Cross 71 - Green Man Lane 44 - New Avenue Estate 12 - Connaught Estate 23 - Reginald Road 19 - Carpenters Estate 35 - Heygate Estate 9 - Thames View 61 - West Hendon 72 - Allen Court 47 - Ladderswood Way 14 - Maryon Road Estate 25 - Pepys Estate 36 - Elmington Estate 10 - Gascoigne Estate 62 - Grahame Park 15 - Grove Estate 28 - Kender Estate 68 - Stonegrove & Spur 73 - Havelock Estate 74 - Rectory Park 16 - Ferrier Estate Estates 75 - Leopold Estate 53 - South Kilburn 63 - Church End area 50 - Watermeadow Court 1 - Darlington Gardens 18 - Excalibur Estate 51 - West Kensingston 2 - Chippenham Gardens 38 - Myatts Fields 64 - Chalkhill Estate 45 - Tidbury Court 42 - Westbourne area & Gibbs Green Estates 3 - Briar Road Estate -

Community-Led Regeneration

Community-Led Regeneration Community-Led Regeneration A Toolkit for Residents and Planners Pablo Sendra and Daniel Fitzpatrick First published in 2020 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Text © Authors, 2020 Images © Authors and copyright holders named in captions, 2020 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Sendra, P. and Fitzpatrick, D. 2020. Community-Led Regeneration: A Toolkit for Residents and Planners. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111. 9781787356061 Further details about Creative Commons licences are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons licence unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material. If you would like to reuse any third-party material not covered by the book’s Creative Commons licence, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-1-78735-608-5 (Hbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-607-8 (Pbk.) ISBN: 978-1-78735-606-1 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-78735-609-2 (epub) ISBN: 978-1-78735-610-8 (mobi) DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787356061 Contents List of figures vii List of abbreviations x List of contributors xi Preface by Richard Lee and Michael Edwards, Just Space xiii Acknowledgements xvi Introduction 1 Part I: Case Studies 9 1. -

Annual Report 2011/12

Community-Police Consultative Group for Lambeth Artists courtesy of www.paintshopstudio.com Annual Report 2011/12 Have Your Say on Policing in London Annual Report 2011/12 Contents Page Chair's Report………………………..……………………………………………………..…………....2 Stop and Search Sub-Group Report…………………………………………………………………...8 Mental Health Sub-Group Report……………………………………………………………………..14 Safer Neighbourhood Panels' Report…………………………………………………………………15 Honorary Comptroller's Report………………………………………………………….……………..17 Finance…………………………………………………………………………………………………...22 including Annual Accounts Appendix: Membership….…………………………………………………………………………..….25 www.lambethcpcg.org.uk 1 Annual Report 2011/12 Chair’s Report During my time with the CPCG Lambeth I have seen many a cause championed and dire situations rescued with our intervention. I was also privileged to witness the creation of The Lambeth Black Families Forum (LBFF) this year chaired by our very own Sandra Moodie and Vince McBean from The West Indian and ex Service Personnel (WASP) and supported by Lambeth Police and the Council. An Inspirational moment In April 2011 saw: Ivelaw Bowman, Cheryl Sealy and Wesley Stephenson honoured by Operation Trident Occupational Command Unit with Commendations for work above and beyond the call. This was a moment where we all publicly acknowledged CPCG for Lambeth and the work we do as we believe: 'the group is the group and we stand for something together' I have seen the tears and despair of families coping with the loss of loved ones gunned down or tragically stabbed in their prime due to gang or area code issues or death following police contact. More alarmingly, is the on-going question of our youth service and the youth clubs available to them as their environment seems to be vanishing right before their eyes. -

C20 CA Project Short Reports on Potential Conservation Areas

Conservation Areas Project Potential Conservation Areas Short Reports December 2017 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction Section 10.3.2 of the Brief for the Twentieth Century Society Conservation Areas Project requires the research consultants ‘to prepare summaries of around 50 areas that have potential for future conservation area status, providing information on their location, the architect, date of construction, borough, one or two images and a short paragraph about the site’. These short reports are listed in Section 2.0 below, and the full reports follow, in numerical order. All the short reports follow a standard format which was agreed by the Steering Group for the Project (see appendix 3 of the Scoping Report). The reports are intended principally as identifiers not as full descriptions. In line with the research strategy, they are the result of a desk-based assessment. The historic information is derived mainly from secondary sources and the pictures are taken largely from the Web (and no copyright clearance for future publication has been obtained). No specific boundaries are suggested for the potential conservation areas because any more formal proposals clearly need to be based on thorough research and site inspection. 2.0 List of Potential Conservation Areas Historic County Area Name Local Planning Record Authority Number Berkshire Blossom Avenue, Theale West Berkshire 01 Buckinghamshire Energy World Milton Keynes 02 Buckinghamshire Woolstone Milton Keynes 03 Cheshire The Brow, Runcorn Halton 04 Devon Sladnor Park Torquay 05 Dorset -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 628 5 September 2017 No. 22 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 5 September 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Damian Green MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. David Davis, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Sir Michael Fallon, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH—The Rt Hon. Jeremy Hunt, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Justine Greening, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRANSPORT—The Rt Hon. -

Conservation Areas Project Potential Conservation

Conservation Areas Project Potential Conservation Areas Scoping Report December 2017 CONTENTS 1.0 Summary 2.0 Terms of Reference and Research Methodology 3.0 Research Outcomes 3.1 Exemplary Projects 3.2 Suggested Potential Conservation Areas 4.0 Themes & Issues 4.1 Bombed Towns & Cities 4.2 New Towns 4.3 Public Housing Developments 4.4 Private Housing Developments 4.5 University Campuses 4.6 Single Design 4.7 Single Ownership 4.8 Tall Buildings 4.9 Negative Perceptions about Designation of Twentieth Century Conservation Areas 5.0 Conclusions Appendix 1. Designating Conservation Areas which include C20th Buildings: Good Practice Guidelines Appendix 2. List of Potential Conservation Areas Appendix 3. Potential Conservation Areas – Data Capture Form Template Appendix 4. Exemplary Projects Draft Criteria Appendix 5. Existing C20 Conservation Areas 2 3 1.0 SUMMARY This report summarises the outcomes of research undertaken as part of a wider project exploring conservation area designation for twentieth century structures and landscapes. The report was commissioned in 2017, the 50th Anniversary of the 1967 Civic Amenities Act which established the principle of Conservation Area designation. The rationale for the whole project is the recognition by both The Twentieth Century Society and Historic England that twentieth century heritage is often under-valued and vulnerable. There is clearly a need for improved protection in those cases where statutory listing cannot be justified but the heritage if of sufficient merit to justify some protection. There is also recognition of the benefits to be had from raising awareness of the contribution that twentieth century heritage makes to the wider historic built environment and of the benefits of preserving that heritage through conservation area designation. -

Appendix a Resident Engagement in Housing Development

Appendix A Resident engagement in housing development: A scrutiny review by the Housing Select Committee Summary of evidence and main themes December 2019 Table of Contents Early resident engagement ........................................................................................ 1 Identifying local issues and context ........................................................................ 3 Trust, transparency and information ....................................................................... 4 Engagement during the planning process .............................................................. 6 Active and ongoing engagement ................................................................................ 7 A range of methods ................................................................................................ 7 The design stage .................................................................................................... 8 Boundaries and levels of engagement .................................................................... 9 Open and honest engagement ............................................................................. 11 TRA involvement .................................................................................................. 11 Seldom-heard groups and capacity building ............................................................ 12 Resident support and capacity building ................................................................ 14 Early resident engagement 1.1 Engaging with residents -

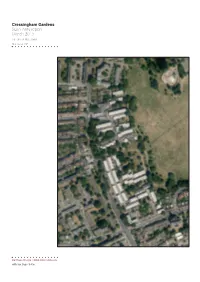

Cressingham Gardens Summary Report March 2015 A3 Format Document Status: DRAFT

Cressingham Gardens Summary report March 2015 A3 format document Status: DRAFT Karthaus Design | RIBA Client Advisers with Ian Sayer & Co. Cressingham Gardens Summary report Contents Executive Summary page 3 1. Summary of the options pages 4-11 2. Existing site pages 12-16 3. Introductory workshop pages 17-18 4. Development envelopes pages 19-27 5. Development cost estimates pages 28-31 6. Additional information pages 32-41 Contacts page 42 Karthaus Design with Ian Sayer & Co. | www.karthaus.co.uk | www.iansayer.co.uk 2 Cressingham Gardens for Lambeth Council | Final Report | March 2015 Cressingham Gardens Summary report Executive Summary This report draws together the work carried out by Karthaus Design at Cressingham Gardens since our original commission in September 2013. Our brief was to support the Council’s consultants Social Life in a series of deliberative workshops to explore possible options for the future of the estate. Meetings were held with planning officers to establish a realistically achievable development volume and some key principles that development should follow. In accordance with our detailed brief, a series of ‘massing envelopes’ or ‘volumes’ of development was produced to show different scales of redevelopment possible on the estate, from refurbishment and minimal ‘infill’ through to a full demolition and redevelopment. These massing envelopes were intended to enable a high-level discussion and testing of the future options for the estate, together with the residents prior to the commencement of a design process. On conclusion of this work and a preferred option being identified, the outcome would be the basis for a design brief for the estate to be progressed by a design team yet to be appointed by the Council.