An Amicus Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom from Religion Foundation Year in Review — 2016

Freedom From Religion Foundation Year in Review — 2016 Many Kick the Habit – Become Nones As this is written, FFRF has 24,000 current members and count- ing — hundreds are joining (300 since Nov. 8). FFRF’s also em- barking on a major digital advertising campaign to turn some of our 450,000 Facebook “friends” into active supporters so FFRF can speak up for them and you with an even more powerful voice. If you know of a likely prospective member, let us know! We’d be glad to send them a complimentary issue of our newspaper, brochure and invitation to join us: ffrf.org/info or phone 1-800- 335-4021. Extra! Extra! FFRF makes the news! FFRF welcomed in February Amit Pal, a seasoned alumnus of The Progressive magazine who oversaw the magazine and its op- ed Media Project for many years, as our first communications di- rector. Amit has written or overseen more than 300 news releases and 50 action alerts since being hired, polishing and broadening Photo: Chris Line FFRF’s communications. His charming special weekly email up- FFRF’s “unabashed” staff and interns, October 2016. dates keep you informed in between issues of Freethought Today New Year’s resolution: Look for FFRF’s upcoming TV show of all the legal victories, complaints, and media being generated. and more videos produced in the Stephen Uhl Friendly Atheist Thanks to Amit’s productivity and Communications Assistant Studio in 2017! Lauryn Seering’s efficiency in alerting the media, FFRF’s state/ FFRF restores historic Ingersoll statue church work, litigation and educational campaigns generated over 1,600 bona fide news stories about FFRF in daily and online me- FFRF quickly raised funds — dia outlets, plus 196 local and nationwide TV news segments. -

Translation Ellehumanist Ur S

. ! se rv ic e e a m n p d a t p hy a r t i c i a p l a tr t i u o is n m ility um h – e t h ic a l d e v e l o p m e n t peace and ice l just cia so critical thinking responsibility s gl s ob e al awaren e n vironmental ism ، American Humanist Association: www.americanhumanist.org Humanist Manifesto: www.americanhumanist.org/what-is-humanism/manifesto3/ The Ten Commitments: www.humanistcommitments.org Effective Altruism: https://www.effectivealtruism.org Camp Quest: www.campquest.org Foundation Beyond Belief: https://foundationbeyondbelief.org Oasis: www.networkoasis.org Sunday Assembly: www.sundayassembly.com Unitarian Universalist Association: www.UUA.org Center For Inquiry: www.centerforinquiry.org Freedom From Religion Foundation: www.ffrf.org American Ethical Union: www.aeu.org Secular Student Alliance: www.secularstudents.org Skeptic Society: https://www.skeptic.com Black Non-Believers www.blacknonbelievers.com Hispanic American Freethinkers: http://hafree.org Freethought Society: www.ftsociety.org Friendly Atheist: www.friendlyatheist.patheos.com Thinking Atheist: www.thethinkingatheist.com American Atheists: www.atheists.org Annabelle & Aiden Book Series: www.annabelleandaiden.com Stardust Book Series: www.stardustscience.com Society for Humanistic Judaism: www.shj.org Openly Secular: www.openlysecular.org Secular Coalition: www.secular.org Teacher Institute for Evolutionary Science: www.tieseducation.org Richard Dawkins Foundation: www.richarddawkins.net Humanists International: www.humanists.international Humanist Community -

Lori L. Fazzino

Lori L. Fazzino Department of Sociology Phone: 702-895-3322 University of Nevada, Las Vegas Email: [email protected] 4505 Maryland Parkway Website: Box 455033 http://faculty.unlv.edu/wpmu/lfazzino/ Las Vegas, NV 89154 EDUCATION Ph.D. Candidate, Sociology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2016 (expected) Committee: Michael Ian Borer (chair); Robert Futrell; David R. Dickens; Ian Dove (graduate college representative); Ryan T. Cragun (outside member) Comprehensive Exams: Culture; Social Movements DISSERTATION Good Without God in the City of Sin: The Making of Irreligious Morality in the Las Vegas Atheist Community My dissertation examines the lived experience of everyday irreligion, specifically looking at constructions of irreligious moral order(s) vis-a-vis dominant moral discourse. Because irreligion is a response to religion from the position of a “moral other,” this dissertation is also concerned with exploring “othering” as a form of moral injury and cultural trauma. Understanding the construction and performance of irreligious morality as individual and collective acts of cultural and political resistance, particularly in a digitally mediated urban environment, will tell us much about how global citizens are attempting to change the face of social justice in the 21st century and how historically marginalized populations cope with their specific legacies of moral injustice. M.A. Sociology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2012 B.A. Magna cum laude, Pacific Lutheran University 2010 Major: Sociology, Minor: Philosophy, RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Religion, Culture, Deviance, Social Movements, Theory, and Gender/Embodiment PUBLICATIONS Refereed Journal Articles Fazzino, Lori L. 2014. “Leaving the Church Behind: Applying a Deconversion Perspective to Evangelical Exit Narratives.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 29 (2): 249-266. -

American Atheists 2019 National Convention

AMERICAN ATHEISTS 2019 NATIONAL CONVENTION APRIL 19–21, 2019 Hilton Netherland Plaza Hotel Cincinnati, OH EVERYDAY ATHEISM EXTRAORDINARY ACTIVISM FROM EVERYDAY PEOPLE CONFERENCE AGENDA YOUR NAME Table of Contents Convention Site Layout ......................................................2 Exhibitors and Guests ..........................................................3 Service Project ..........................................................................4 Recording Policy ......................................................................4 Meet Your Emcee ...................................................................5 Convention Schedule Thursday ..............................................................................5 Friday ......................................................................................6 Saturday ...............................................................................8 Sunday ..................................................................................10 Convention Speakers ...........................................................11 God Awful Movies LIVE! .....................................................17 Saturday Main Stage ............................................................18 Saturday Workshops ............................................................19 Full Code of Conduct ...........................................................23 Join the Conversation American Atheists @AmericanAtheist #AACon2019 Convention Layout Fourth Floor Freight Rosewood Elevator Rosewood -

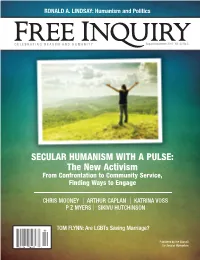

SECULAR HUMANISM with a PULSE: the New Activism from Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage

FI AS C1_Layout 1 6/28/12 10:45 AM Page 1 RONALD A. LINDSAY: Humanism and Politics CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No.5 SECULAR HUMANISM WITH A PULSE: The New Activism From Confrontation to Community Service, Finding Ways to Engage CHRIS MOONEY | ARTHUR CAPLAN | KATRINA VOSS P Z MYERS | SIKIVU HUTCHINSON 09 TOM FLYNN: Are LGBTs Saving Marriage? Published by the Council for Secular Humanism 7725274 74957 FI Aug Sept CUT_FI 6/27/12 4:54 PM Page 3 August/September 2012 Vol. 32 No. 5 CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY 20 Secular Humanism With A Pulse: 30 Grief Beyond Belief The New Activists Rebecca Hensler Introduction Lauren Becker 32 Humanists Care about Humans! Bob Stevenson 22 Sparking a Fire in the Humanist Heart James Croft 34 Not Enough Marthas Reba Boyd Wooden 24 Secular Service in Michigan Mindy Miner 35 The Making of an Angry Atheist Advocate EllenBeth Wachs 25 Campus Service Work Franklin Kramer and Derek Miller 37 Taking Care of Our Own Hemant Mehta 27 Diversity and Secular Activism Alix Jules 39 A Tale of Two Tomes Michael B. Paulkovich 29 Live Well and Help Others Live Well Bill Cooke EDITORIAL 15 Who Cares What Happens 56 The Atheist’s Guide to Reality: 4 Humanism and Politics to Dropouts? Enjoying Life without Illusions Ronald A. Lindsay Nat Hentoff by Alex Rosenberg Reviewed by Jean Kazez LEADING QUESTIONS 16 CFI Gives Women a Voice with 7 The Rise of Islamic Creationism, Part 1 ‘Women in Secularism’ Conference 58 What Jesus Didn’t Say A Conversation with Johan Braeckman Julia Lavarnway by Gerd Lüdemann Reviewed by Robert M. -

ENVISIONING a BETTER WORLD Secular Student Alliance Virtual Conference • July 22-25, 2020

ENVISIONING A BETTER WORLD Secular Student Alliance Virtual Conference • July 22-25, 2020 Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 9:00 Pacific Daylight Time 9:00 Pacific Daylight Time 9:00 Pacific Daylight Time 10:00 Pacific Daylight Time Conference Kick-off What You Need to Know Gender, Race, and Power Religious Nationalism: A Kevin Bolling About Humanism & Race Angela Saini Threat to Democracy Secular Student Alliance Anthony Pinn Katherine Stewart 10:15 10:15 10:15 11:15 Humanists At Risk In Conversation Living Our Humanist The Founding Myth Gary McLelland Reps. Jared Huffman, Pramila Values Andrew Seidel Humanist International Jayapal, and Jamie Raskin Emily Newman & Kristin Wintermute 11:40 11:40 11:40 12:20 Finding Realness, Lobby Your Elected Staring Into the Void: Can A Reading: Meaning, and Belonging Officials: Panel Discussion Existential Therapy Help? Elle the Humanist in Our Digital Lives Secular Coalition for America Cara Santa Maria Elle Harris Chris Stedman 12:50 12:50 12:50 12:40 Community and Resilience Supporting Secular Out of the Ashes: Humanists In the Hood in Times of Crisis Students at Home During Imagining Better Sikivu Hutchinson Varun Soni Covid-19 Communities University of Southern California Mandisa Thomas & Kevin Bolling Isaac Gilles 2:00 2:00 2:00 1:50 Contesting Secular Male Reality Check: Making How to Make a Splash in Mobilize Voters Like a Pro! Supremacy to Build a Nonreligious People Count the Media Sean Rivera Better World Alison Gill Serah Blain & Evan Clark Alex DiBranco American Atheists 3:10 3:10 3:10 3:00 Is Atheism Still Taboo in How to Have Difficult Black Secular College Fighting for Voting Rights Politics? Conversations Students: An Exploration Amanda Scott Hemant Mehta Callie Wright of Margins ACLU J.T. -

To Download This Guide in PDF Format

OPENING MINDS CHANGING HEARTS A Guide to Being Openly Secular A Beginner’s Guide to Becoming Openly Secular. Copyright © 2015 Openly Secular. Some Rights Reserved. Content written by Lori L. Fazzino, M.A., University of Nevada, Las Vegas Graphic design by Sarah Hamilton, www.smfhamilton.com This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International. More information is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Openly Secular grants you permission for all non-commercial uses, including reproduction, distribution, and adaptation, so long as you provide proper credit to Openly Secular and provide others with the same rights you are receiving. ABOUT THE OPENLY SECULAR CaMPAIGN Openly Secular is a coalition project that promotes tolerance and equality of people regardless of their belief systems. Founded in 2013, the Openly Secular Coalition is led by four organizations - Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science, Secular Coalition for America, Secular Student Alliance, and Stiefel Freethought Foundation. This campaign is also joined by national partner organizations from the secular movement as well as organizations that are allies to our cause. OUR MISSION The mission of Openly Secular is to eliminate discrimination and increase acceptance by getting secular people - including atheists, freethinkers, agnostics, humanists and nonreligious people - to be open about their beliefs. www.openlysecular.org SPECIAL THANKS We would like to thank PFLAG, www.pflag.org, and the Secular Safe Zone Project, www.secularsafezone.org, for allowing us to adapt pieces of the Be Yourself: Questions and Answers for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth and the Secular Safe Zone Resource Guide for Allies for this text. -

Kathleen Goodman 116 Marti Court • Oxford, OH 45056 • (703) 585-9582 • [email protected]

Kathleen Goodman 116 Marti Court • Oxford, OH 45056 • (703) 585-9582 • [email protected] Education The University of Iowa 2011 Doctor of Philosophy, Student Affairs Administration and Research Dissertation Title: The Influence of the Campus Climate for Diversity on College Students’ Need for Cognition Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Ernest Pascarella Boston College 1994 Master of Arts, Higher Education Administration The State University of New York at Potsdam 1988 Bachelor of Arts, Cum Laude Major: Cultural Anthropology / Minor: English Writing Research and Teaching Interests The impact of college experiences on student learning Diversity and equity in higher education Student development Spirituality, interfaith dialogue, and atheism Quantitative methods Publications Refereed Journal Articles Goodman, K. M. (under review.) The Effects of the Campus Climate for Diversity on Need for Cognition: Insights from a Quantitative Critical Perspective. Stinson, R. D., Goodman, K. M., Bermingham, C., & Ali, S. R. (2013). Do atheism and feminism go hand-in-hand? A qualitative investigation of atheist men's perspectives about gender equality. Secularism and Nonreligion, 2, 39-60. Seifert, T., Goodman, K., King, P., & Baxter Magolda, M. (2010). Using mixed methods to study first-year college impact. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(3), 248-267. Seifert, T., Pascarella, E., Goodman, K., Salisbury, M., & Blaich, C. (2010). Liberal arts colleges and good practices in undergraduate education: Additional evidence. Journal of College Student Development, 51(1), 1-22. Seifert, T., Goodman, K., Lindsay, N., Jorgensen, J., Wolniak, G., Pascarella, E., et al. (2008). The effects of liberal arts experiences on liberal arts outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 49(2), 107-125. -

2013 Year in Review STOP the PRESS! FFRF WINS MAJOR ‘PARISH EXEMPTION’ SUIT in FEDERAL COURT NOV

Freedom From Religion Foundation 2013 Year in Review STOP THE PRESS! FFRF WINS MAJOR ‘PARISH EXEMPTION’ SUIT IN FEDERAL COURT NOV. 22! FFRF closes in on 20,000 members in Wing (name to be unveiled), Rose Zerwick our 35th year! (in memoriam) Courtyard and Garden. All donors’ names will be memorialized in a The Freedom From Religion Foundation, keepsake book on display. Thank you, ev- which began with 3 original members in eryone! 1976 and was incorporated nationally in 1978, has grown to nearly 20,0000 mem- Public relations/educational campaigns bers nationwide. Help FFRF reach and surpass that 20,000 mark! Please let freethinking friends and family “Godless Constitution” campaign. FFRF unveiled a know about FFRF. The curious may request a sample Founding Fathers full-page ad to counter Religious Right packet, including a free issue of Freethought Today, at: disinformation by Hobby Lobby, promoting our “Godless ffrf.org, or phone 1-800-335-4021. Constitution” in 24 newspapers on July 4, including The New York Times. (The Oklahoma City daily, where Hob- Steven Pinker accepts new by Lobby is based, censored our ad.) Several kind FFRF Honorary President position members have since placed a version of this ad for Con- stitution Day (Sept. 17) and Bill of Rights Day (Dec. 15). Harvard experimental psychologist Ste- Lies by the Religious Right should never go uncorrected. ven Pinker, a leading intellectual, author and committed state/church separationist, Scientific American ads. Thanks to a $25,000 grant has accepted FFRF’s invitation to serve as FFRF’s first from Lester Goldstein, matched by donors, FFRF is Honorary President. -

February 12, 2019 Raúl M. Grijalva Chairman

February 12, 2019 Raúl M. Grijalva Chairman House Committee on Natural Resources 1324 Longworth House Office Building Washington, DC 20515 Dear Chairman Grijalva, The undersigned organizations, who advocate for the rights of the nearly 95 million Americans who are nonreligious, write to express our deep concern with the House Committee on Natural Resources’ recent vote to retain the phrase “so help me God” in the oath taken by hearing witnesses. We were incredibly heartened when early reports claimed that the committee was preparing, at your direction, to vote on an amendment that would make the “God” clause optional. Removing the requirement to recite this clause is a long-overdue step that would bring the committee in line with the overwhelming majority of Americans who support the constitutional separation of church and state in law and in spirit. We saw the vote as an opportunity for the new Congressional majority to show leadership in making our government inclusive of all Americans regardless of their religious belief or lack thereof. We were shocked when a religious television network reported that you later called the draft proposal a “mistake.”1 It is never a mistake to fight for religious equality and inclusive government. The requirement to swear loyalty to a deity is a clear violation of the religious freedom enshrined in the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution, which requires the government to maintain neutrality not just between different religions, but also between religion and non-religion.2 According to the Pew Research Center, 29 percent of adults in the United States have no religious beliefs.3 To Americans with deep and sincerely held beliefs that are non-religious, a mandatory “God” clause sends the message that they are second-class citizens and not “real” Americans. -

Bruce Gleason - Examining “Woo”

The HSSB Secular Circular – August 2020 1 Newsletter of the Humanist Society of Santa Barbara www.SBHumanists.org AUGUST 2020 Please join us for our August Speaker Meeting on Zoom… Bruce Gleason - Examining “Woo” Examining “Woo” is a presentation about all things magical, mystical, and absolutely, totally useless. Bruce will scrutinize many common non-scientific medical procedures, religion- based infomercial scams, homeopathy, GMOs, and gay conversion therapy. He will discuss how to tell what is more likely to be true and will examine the psychology of conspiracy theorists. He will also review why our species is so susceptible to confirmation bias and so often comfortable with cognitive dissonance. Bruce Gleason has been involved in the atheist, skeptic and humanist communities for 16 years. Founder of the Backyard Skeptics Meetup with over 1300 members, he has placed over 14 billboards supporting the secular community. He creates two annual conferences: LogiCal-LA, a scientific skeptics’ event, and the Freethought Alliance Conference, which is for atheists, agnostics, and church-state separatists. Both conferences are currently postponed due to Covid-19. Bruce is a professional videographer and supplies critical audio Bruce Gleason, Founder of visual equipment for conferences such as the American Backyard Skeptics; creator of Humanist and American Atheists conferences. He worked at LogiCal-LA and Freethought ABC Television in Hollywood for several years. Alliance Conference. When: Saturday, August 15, via Zoom. Log in as early as 2:45 pm. Program begins at 3pm. Where: Zoom link https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84572611448. For those ONLY joining with phone audio, dial 1-669-900-9128 then enter meeting id 84572611448# COVID-19 Pandemic Models Update Dave Flattery will present his 7th update on the state of the COVID-19 pandemic on Sunday August 23rd at 3pm. -

Supreme Court of the United States ———————————————————————— UNITED STATES of AMERICA, PETITIONER, V

No. 12-307 In The Supreme Court of the United States ———————————————————————— UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PETITIONER, v. EDITH SCHLAIN WINDSOR, et al., RESPONDENTS. _____________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ————————— BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION AND AMERICAN ATHEISTS, INC., AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION, THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY, MILITARY ASSOCIATION OF ATHEISTS AND FREETHINKERS, SECULAR COALITION FOR AMERICA, SECULAR STUDENT ALLIANCE, AND SOCIETY FOR HUMANISTIC JUDAISM, IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ADDRESSING THE MERITS ————————— WILLIAM J. BURGESS ELIZABETH L. HILEMAN MONICA MILLER Counsel of Record Appignani Humanist Hileman & Williams, P.C. Legal Center 7979 Old Georgetown Rd. American Humanist Bethesda, Md. 20814 Association (301) 652-1448 1777 T Street, N.W. [email protected] Washington, D.C. 20009 (202) 238-9088 [email protected] Attorneys for Amici Curiae ══════════════════════════════════ TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................... i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................... iii INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE ................................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................................... 3 ARGUMENT .................................................................. 5 I. DOMA VIOLATES EQUAL PROTECTION BECAUSE IT REFLECTS AND PERPETUATES PREJUDICE TOWARDS A PROTECTED CLASS AND IS NOT JUSTIFIED BY ANY VALID GOVERNMENTAL INTEREST ................. 5 A. Laws such as DOMA,