Chapter 1 Introduction This Book Is Written for Anyone Who Has Ever Wondered What the Bible Really Teaches About Mary, the Mothe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Mary of the Annunciation | Mundelein

Vision: That all generations at St. Mary and in the surrounding community encounter Jesus and live as His disciples. Mission: We are called to go out and share the Good News, making disciples who build up the Kingdom of God through meaningful prayer, effective formation and loving service. SAINT MARY OF THE ANNUNCIATION | MUNDELEIN Mass Schedule: Follow us on social media: Sat. 5:00 PM Sun. 7:30, 9:30,11:30 AM Weekday Mass Schedule: Monday - Friday, 8:00 AM @stmarymundelein www.stmaryfc.org Confessions: Saturday, 4:00–4:45 PM Mass May 10—May 16, 2021 Stewardship Report Sunday Collection May 02, 2021 $ 25,072.57 Monday, May 10, 8:00AM Budgeted Weekly Collection $ 22,115.38 † Jim Monahan Wife Shirley Difference $ 2,957.19 † Lottie Cnota Cnota Family Tuesday, May 11, 8:00AM Current Fiscal Year-to-Date* $ 970,846.93 † Frank Metcalf Daughter Victoria Hansen Budgeted Sunday Collections To-Date $ 973,076.92 Wednesday, May 12, 8:00 AM Difference $ (2,229.99) † Brad Hansen, Sr. & Danny Hansen Carol Hansen Family Difference vs. Last Year $ (25,860.21) † Maria Vullo Daughter Fran & Duane Schmidt † Salvatore & †Michelina Panettieri The Family *Note: YTD amount reflects updates by bank to postings and adjustments. † Rose Schmidt Son Duane & Fran Schmidt Thursday, May 13, 8:00 AM LIVING Gene Murden Sister Mary Lou Loomis Do you know someone missing the † Anne R. Golm Victoria Hansen parish bulletin each week? Friday, May 14, 8:00 AM For those not able to pick up a copy of † Sophia Barthuly Husband Ron the bulletin at Mass there are several Wedding Saturday, May 15, 2:30PM ways to receive the St. -

The Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time August 1St, 2021

2200 S.E. Cove Rd Stuart, Fl 34997 Phone (772) -781-4418 Fax: (772)-743-6127 The Eighteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time August 1st, 2021 819- 819-1 Saint Andrew Catholic Church 2100 SE Cove Road Adult Education (RCIA) Stuart, Florida 34997 & Lectors 772-781-4415 Christine Michaelian Thursday 6:30pm-8:00pm July 31 Sat. 4:00pm Callie Frances Sharp+ Adoration Aug 1 Sun. 7:30am The Harden Family+ M-F 8:00am –12m in Church Mo Wallace Aug 1 Sun. 9:00am Robin Srebot Ziesmer+ [email protected] 772-285-2688 Aug 1 Sun. 10:30am Manuel Higuera+ Saturday Vigil: 4:00pm Servants of the Eucharist & Sunday: 7:30, 9:00 & 10:30am Aug 2 Mon. 7:30am Robert Paul Bretherick+ Care of the Sick Monday-Friday 7:30am Kathleen Sullivan Holy Days: Vigil 4:00pm Aug 3 Tues. 7:30am Rita Zuendt+ 7:30am & 6:00pm Annulments Aug 4 Weds. 7:30am Thomas + & Phyllis Cote (Liv) John Ginnetti Confession: Aug 5 Thurs. 7:30am Mary Towers+ Men of Saint Andrew Saturday: 2:30pm Dave Olio Those wishing to receive the Aug 6 Fri. 7:30am The Parrini Family (Liv & +) Monday evening 6:30-8pm sacrament [email protected] should be here at 2:30 Aug 7 Sat. 7:30am Colleen & Dick Venezia(Liv) Prayer Shawl Ministry First Friday Aug 7 Sat. 4:00pm Pauline Becker (Liv) Norma Olio 7:30am Mass followed 1st Wednesday of each month by individual confessions Aug. 8 Sun. 7:30am Aaron Banasiewicz (Liv) 10:30 am Aug. 8 Sun. 9:00am Melanie Gallagher (Liv) Pro-Life Ministry First Saturday Michele Williams 7:30 Mass followed by individual Aug. -

The Catholic University of America A

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By John H. Osman Washington, D.C. 2015 A Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity: A Neglected Catechetical Text of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore John H. Osman, Ph.D. Director: Joseph M. White, Ph.D. At the 1884 Third Plenary Council of Baltimore, the US Catholic bishops commissioned a national prayer book titled the Manual of Prayers for the Use of the Catholic Laity and the widely-known Baltimore Catechism. This study examines the Manual’s genesis, contents, and publication history to understand its contribution to the Church’s teaching efforts. To account for the Manual’s contents, the study describes prayer book genres developed in the British Isles that shaped similar publications for use by American Catholics. The study considers the critiques of bishops and others concerning US-published prayer books, and episcopal decrees to address their weak theological content. To improve understanding of the Church’s liturgy, the bishops commissioned a prayer book for the laity containing selections from Roman liturgical books. The study quantifies the text’s sources from liturgical and devotional books. The book’s compiler, Rev. Clarence Woodman, C.S.P., adopted the English manual prayer book genre while most of the book’s content derived from the Roman Missal, Breviary, and Ritual, albeit augmented with highly regarded English and US prayers and instructions. -

S OK Not to Like Some Devotions —

It’s OK not to like some devotions — here’s why Although you may never mention it to anyone, it’s not some dirty little secret or large fault to not like some Catholic devotions. They may not appeal to you and, more importantly, when you give them an honest try, you don’t find them spiritually helpful. Perhaps — yikes! — you even find them a little annoying or burdensome. Devotions mandated in Scripture This isn’t to say Catholicism is a make-it-up-yourself kind of religion with do-it-yourself theology. Not at all. So let’s start by pointing out some hard-and-fast basic devotions that all Catholics practice: The Eucharist and the other sacraments: “Do this in memory of me” (Lk 22:19). The Blessed Virgin Mary: “Behold your mother” (Jn 19:27). The Our Father: “Lord, teach us to pray” (Lk 11:1). Private prayer: “He went up on the mountain by himself to pray. When it was evening he was there alone” (Mt 14:23). Scripture: “He interpreted to them what referred to him in all the scriptures” (Lk 24:27). Dogma: “Amen, I say to you, whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Mt 18:18). So what’s missing? All the wonderful devotions and practices that the Church has created since the end of apostolic times. (That is, the death of the last apostle who, tradition says, was John.) Some of those devotions and practices have been, and remain, hugely popular and incredibly helpful to countless people. -

What Is the Angelus? “The Angel of the Lord Declared Unto Mary…” D.D. Emmons the Catholic Answer

What Is the Angelus? “The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary…” D.D. Emmons The Catholic Answer 4/4/2011 Among our many Catholic devotions, few are more beautiful or have been contemplated more often than the Angelus. Designed to commemorate the mystery of the Incarnation and pay homage to Mary’s role in salvation history, it has long been part of Catholic life. Around the world, three times every day, the faithful stop whatever they are doing and with the words “The Angel of the Lord declared unto Mary” begin this simple yet beautiful prayer. But why do we say the Angelus at all, much less three times a day? A review of Church history shows that this devotion did not appear suddenly, but developed over several centuries. Called By the Bell Most Church historians agree that the Angelus can be traced back to 11th- century Italy, where Franciscan monks said three Hail Marys during night prayers, at the last bell of the day. Over time, pastors encouraged their Catholic flocks to end each day in a similar fashion by saying three Hail Marys. In the villages, as in the monasteries, a bell was rung at the close of the day reminding the laity of this special prayer time. The evening devotional practice soon spread to other parts of Christendom, including England. Toward the end of the 11th century, the Normans invaded and occupied England. In order to ensure control of the populace, the Normans rang a curfew bell at the end of each day reminding the locals to extinguish all fires, get off the streets and retire to their homes. -

For Review Only. Copyright Our Sunday Visitor, Inc

St. Joseph, who provided For Further Reading a home to the child Jesus, is Novena Prayer to St. Jude often invoked by Catholics The How-To Book of Catholic Devotions (Our Sunday needing to sell a home (The following prayers are repeated once a day for nine Visitor), Mike Aquilina and Regis Flaherty. (www.stjosephsite.com/ consecutive days.) The Church’s Most Powerful Novenas (Our Sunday SJS_Prayer_To sell a home. Most holy Apostle St. Jude, faithful servant and Visitor), Michael Dubruiel. htm) friend of Jesus, the name of the traitor who deliv- Treasury of Novenas (Catholic Book Publishing), ered your beloved Master into the hands of His Father Lawrence Lovasik. St. Thérèse of Lisieux, enemies has caused you to be forgotten by many, also called the Little Flower, but the Church honors and invokes you universally General Novena Prayers is popular among many as the patron of hopeless cases, www.catholiclinks.org/novenasenglish.htm today who pray various of things almost despaired of. novenas to her for help in Pray for me, I am so help- all kinds of situations less and alone. Make use, I (www.ewtn.com/therese/ implore you, of that particu- novena.htm). Shutterstock lar privilege given to you, to bring visible and speedy Inc. The Crossiers help where help is almost despaired of. Come to my How Do I Pray assistance in this great need, that I may receive the consola- To view a PDF of additional topical pamphlets or to order bulk copies of this pamphlet, go to a Novena? tion and help of heaven in all my www.osv.com/pamphlets Only.Visitor, There are many ways to necessities, tribulations, and sufferings, pray a novena. -

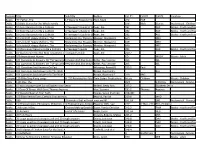

Resource Typetitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2

ResourceTitle Type Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 Location Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Stories Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide to theAuer, Church Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide to theAuer, Church Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide to theAuer, Church Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 MEE Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 MEE Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 MEE Books 10 More Good Reasons to Be a Catholic A Teenager's Guide Auer, Jim 282 AUE Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Ways to Get Into the New Testament, A Teenager's Guide Auer, Jim 220.7 Compact 100Discs Inspirational Hymns CD MUSIC Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 KEL Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 KEL Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact 101Discs Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. -

SAMPLE © Twenty-Third Publications

hen someone mentions “Catholic devotions,” perhaps you think of a group of little Wold ladies gathered in the church to pray the Rosary. Or maybe you remember your own parents’ prayers to a particular saint years ago. But devotions do not have to be just for old ladies or a thing of the past. They can be an enriching part of your faith life and an inspiring part of your personal prayer practice today. Devotions are meaningful ways we can engage in prayer to Jesus, Mary, and the saints—beyond how we honor God with our words and actions through- outSAMPLE our busy days. They are not meant to replace the liturgy but to extend it into our daily lives. Indeed, the life of the church centers on the lit- urgy. The Second Vatican Council teaches us that “the liturgyTwenty-Third is the summit toward which the activ- ©ity of the church is directed; at the same time it is Twenty-ThirdPublications Publications, a Division of Bayard, One Montauk Avenue, Suite 200, New London, CT 06320, (860) 437-3012 or (800) 321-0411, www.twentythirdpublications.com. ISBN 978-1-62785-471-9 • Cover image: iStockphoto.com / D-Keine Copyright © 2019 Danielle Bean. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission of the publisher. Write to the Permissions Editor. Printed in the U.S.A. the font from which all her power flows.” And while we cannot spend all day, every day, at Mass, St. Paul encour- ages us to “pray without ceasing” (1 Thessalonians 5:17). -

The Virgin Mary: a Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive National Collegiate Honors Council Spring 2007 The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century Darris Catherine Saylors University of Tennessee - Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Saylors, Darris Catherine, "The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century" (2007). Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive. 31. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nchcjournal/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Collegiate Honors Council at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council --Online Archive by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DARRIS CATHERINE SAYLORS The Virgin Mary: A Paradoxical Model for Roman Catholic Immigrant Women of the Nineteenth Century DARRIS CATHERINE SAYLORS 2006 NCHC PORTZ SCHOLAR UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE AT CHATTANOOGA INTRODUCTION his paper identifies and discusses several examples of Marian paradoxes Tto better understand how constructions of Mary as the primary model of feminine religiosity affected Roman Catholic immigrant women. Such para- doxes include Mary’s perpetual virginity juxtaposed with earthly women’s commitment to family (and the sexual relationship implicit in marriage) and the classist elements inherent in the True Womanhood model related to Mary. -

LENT 2016 of Mercy CATHOLIC RESOURCE CATALOG

Celebrate the Jubilee Year of Mercy Pages 18-19 LENT 2016 CATHOLIC RESOURCE CATALOG CREATIVEcreativecommunications.com COMMUNICATIONS |FOR 1-800-325-9414 THE PARISH Lenten Devotional Booklets *prices listed are per book per title Taking Lent Also available on to Heart All Stories and Booklets Reflections for Lent as By Fr. Thomas J. Connery low ¢ as 49 Taking Lent to Heart: Stories and each Reflections for Lent is filled with easy- to-read yet thoughtful and heartfelt reflections for each day of the season. Based on Scripture readings, this bounty of Fr. Thomas Connery’s wit and wisdom will serve as an ideal companion for us as we journey closer to the Lord each day of this season of preparation. Lenten Devotional Booklets Devotional Lenten As Fr. Connery reminds us in this light and thought-provoking booklet, Lent provides us with “40 days of op- portunity.” Those 40 days are far from being all somber and serious. Code TCA • Paper • 48 pages • 5⅜" x 8⅜" A Place for Also available on Prayer Daily Prayers for Lent By Carol Geisler Mercy, Passion & Joy Our Lord taught us to pray and, model- Lenten Devotions ing what he taught, he himself spent Reflections on the Writings of C. S. Lewis time in prayer to his Father. Jesus prayed Let the writings of C. S. Lewis lead you through Lent with this booklet with and for his disciples. He prayed of daily quotes from arguably the greatest Christian apologist of the alone, going off to desolate places and 20th century, followed by reflections by C. -

Some Simple Suggestions for Prayer During This Time of Anxiety

SOME SIMPLE SUGGESTIONS FOR PRAYER DURING THIS TIME OF ANXIETY It is true for everyone, but certainly so for people of faith, that it is important to take all necessary precautions, observe governmental directives and to take the medical situation seriously, but at the same time to be calm and not to panic Above all, let us also not forget the importance of PRAYER. Our Catholic faith is very practical: we know well how it can help us navigate through tough and anxious times. We know too how important it can be to help our children and young people pray and to pay with them, especially in the disruptive and worrying situation they are experiencing at the moment. We also want to pray for others: for those who have died or are sick with the virus and for their families and friends, for all those who care for them, for medical professionals, for scientists working for a vaccine, and for all those who are afraid during this time of uncertainty. Here are a few easy and practical suggestions for prayers at home in this difficult time: • As an individual or as a family, if you cannot get to Mass on a weekend or during the week (or even if you can!), take a little time to read through the Scripture readings of the day. Various publications, apps or websites can give you these. Then spend a few minutes reflecting upon them with some questions in mind: What is the message in the reading? Do I live up to the message? What resolution can I make to live the message better? Then offer some prayers and petitions. -

Catholic Resources the Basics Bible Translations

Thanks be to Thee, my Lord Jesus Christ For all the benefits Thou hast given me, For all the pains and insults Thou hast borne for me. O most merciful Redeemer, friend and brother, May I know Thee more clearly, Love Thee more dearly, Follow Thee more nearly. —St. Richard of Chichester CATHOLIC RESOURCES These listings are by no means all inclusive. They are the ones I have found most helpful, especially as a new Catho- lic. (Note: all podcasts can be found on iTunes although their links go to their home pages.) THE BASICS THE VATICAN The home office. The place for the Pope’s latest homilies, encyclicals, and suchlike. I like that they have a tab for “Vatican Secret Archives.” (www.vatican.va/) UNITED STATES CONFERENCE OF CATHOLIC BISHOPS (USCCB) Daily readings, New American Bible online, Prayer resources, news and issues, and more. (usccb.org) THE CATECHISM OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Next to the Bible, probably the most indispensable book for Catholics. BULLETIN Tons of good stuff in there. BIBLE TRANSLATIONS The New American Bible (NAB) is the only English text approved by the Church for use in U.S. liturgies. How- ever there are many other translations available for devotional reading which confused me considerably until I looked into them more. These all have imprimaturs. NEW AMERICAN BIBLE (NAB) A translation first published in 1970 under the liturgical principles and reforms of the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). NEW AMERICAN BIBLE REVISED EDITION (NABRE) The first major update to the New American Bible text in over 20 years.