SARAH and HAGAR Women of Promise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

God Sees and God Rescues: the Motif of Affliction in Genesis

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY God Sees and God Rescues: The Motif of Affliction in Genesis A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Rawlings School of Divinity In Fulfillment of the Requirements for Thesis Defense RTCH 690 by Emily C. Page 29 June 2020 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction................................................................................................................1 Literature Review.................................................................................................................2 Methodology........................................................................................................................4 Chapter Divisions.................................................................................................................8 Limitations and Delimitations..............................................................................................9 Chapter 2: The Announcement of Affliction in Genesis 15.....................................................11 Introduction........................................................................................................................11 Exegesis of Genesis 15:1–6...............................................................................................11 Exegesis of Genesis 15:7–21.............................................................................................15 Analysis: The Purpose of the Pronouncement of Enslavement.........................................24 Conclusion.........................................................................................................................29 -

Rachel Leket-Mor

Rachel Leket-Mor Associate Librarian Curator, Open Stack Collections Arizona State University Library PO Box 871006, Tempe, AZ 85287–1006 480-965-2618; [email protected] EDUCATION • Master of Arts in Information Resources and Library Science. University of Arizona. Tucson, AZ. 2007. • Master of Arts in Translation Studies. Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv, Israel. Summa cum laude. 2002. MA Thesis: Yaʻakov Orland as a Translator of Children’s Literature. [Hebrew; OCLC 233405350] • Graduate Certificate in Editing. Bar Ilan University. Ramat Gan, Israel, 1993. • Bachelor of Arts in Comparative Literature and General Studies (Hebrew Linguistics, Classics). Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Jerusalem, Israel. 1991. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE • Curator, Open Stack Collections. Arizona State University Library. May 2017–present. Provides leadership for the selection, management, and disposition of openly accessible resources such as government documents, microforms, print collections, and openly-accessible online collections. Spearheads collection reviews, analyses, and collection maintenance activities and projects. Works with, trains, and guides selectors on purchasing materials, working with approval plans, and understanding a variety of selection, acquisition, and purchasing models. • Subject Librarian, Religious Studies, Philosophy, Jewish Studies, Medieval and Renaissance Studies. Arizona State University Libraries. July 2004–April 2017. Provided outreach in all schools, centers, departments and programs that provide curriculum and research in Jewish Studies, the Middle East, Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Religious Studies and Philosophy. Provided specialized reference and research assistance, including in-class library instruction; developed collections in vernacular and non-vernacular languages in all formats; managed funds. • Bibliographer, Jewish Studies. Arizona State University Libraries. October 2002–June 2004. Provided outreach in all schools, centers, departments and programs that provide curriculum and research in Jewish Studies. -

R. Yaakov Emden

5777 - bpipn mdxa` [email protected] 1 c‡qa GREAT PERSONALITIES RAV YA’AKOV EMDEN (1697-1776) 'i`pw oa i`pw'1 `iypd zqpk zia A] BIOGRAPHY 1676 Shabbatai Tzvi died an apostate but his movement was kept alive by Nathan of Gaza, and then beyond Nathan’s death in 1680. 1696 Born in Altona, then in Denmark, son of the Chacham Tzvi. 1700s Studied until age 17 with his father in Altona and then Amsterdam. He was a prolific writer, Talmudist and kabbalist. 1715 Married the daughter of the Rav of Brod, Moravia and studied at his father-in-law’s yeshiva. As well as Talmud, he also studied kabbala, philosophy, Latin and Dutch. 1718 His father and monther died in close succession. He became a jewelry dealer and declined to take a rabbinic post. 1728 Was pressed to accept the position of Rabbi of Emden. Served in Emden for 4 years which he describes very positively. 1733 Returned to Altona where he owned a private synagogue. His relations with many of the successors to his father were strained. Rav Ya’akov Emden 1730s Obtained permission from the King of Denmark to establish a private printing press in Altona and went on to print his famous Siddur. He received some opposition to the siddur which contains his own extensive notes and essays. 1740s He waged a war in life against neo-Sabbateans and their ‘practical kabbala’ - Rav Emden thought that kabbala should again be restricted to the mature talmudist as of old. He joined in the opposition of the young Rav Moshe Chaim Luzzato - see below. -

In/Voluntary Surrogacy in Genesis

The Asbury Journal 76/1: 9-24 © 2021 Asbury Theological Seminary DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2021S.02 David J. Zucker In/Voluntary Surrogacy in Genesis Abstract: This article re-examines the issue of surrogacy in Genesis. It proposes some different factors, and questions some previous conclusions raised by other scholars, and especially examining feminist scholars approaches to the issue in the cases of Hagar/Abraham (and Sarah), and Bilhah-Zilpah/Jacob (and Rachel, Leah). The author examines these cases in the light of scriptural evidence and the original Hebrew to seek to understand the nature of the relationship of these complex characters. How much say did the surrogates have with regard to the relationship? What was their status within the situation of the text, and how should we reflect on their situation from our modern context? Keywords: Bilhah, Zilpah, Jacob, Hagar, Abraham, Surrogacy David J. Zucker David J. Zucker is a retired rabbi and independent scholar. He is a co-author, along with Moshe Reiss, of The Matriarchs of Genesis: Seven Women, Five Views (Wipf and Stock, 2015). His latest book is American Rabbis: Facts and Fiction, Second Edition (Wipf and Stock, 2019). See his website, DavidJZucker.org. He may be contacted at: [email protected]. 9 10 The Asbury Journal 76/1 (2021) “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”1 Introduction The contemporary notion of surrogacy, of nominating a woman to carry a child to term who then gives up the child to the sperm donor/father has antecedents in the Bible. The most commonly cited example is that of Hagar (Gen. -

The Pilegesh in Our Times Haftorah Parashat Chukat Shoftim 11:1-33

בס”ד Weekly Haftorah by Rebbetzin Chana Bracha Siegelbaum The Pilegesh in Our Times Haftorah Parashat Chukat Shoftim 11:1-33 The Connection between the Haftorah and the Torah Reading This week’s haftorah, describes how the people of Israel were attacked by the nation of Ammon, whereupon the elders of Israel called upon Yiftach to battle with Ammon. Yiftach attempted to negotiate a peaceful resolution, by sending a delegation to reason with the king of Ammon; but the latter remained inflexible. Yiftach then successfully led his countrymen in battle. They were victorious and eliminated the Ammonite threat, and Yiftach became the leader of Israel. The haftorah is connected to Parashat Chukat, by teaching us the importance of absolute support for our acknowledged Torah leadership. Yiftach was the recognized leader and a prophet, although logically he wasn’t the most suitable candidate for leadership. His maternal lineage was questionable, and he was not the greatest scholar. Nevertheless, he was accorded the absolute support of the halacha and the people, as the Talmud teaches: “Yiftach in his generation was like Samuel in his generation” (Babylonian Talmud, Rosh HaShana 25b). Likewise, the statute of the Parah Aduma (Red Heifer) described in Parashat Chukat, teaches us the importance of accepting the laws of the Torah, even when we are unable to understand their reason. Thus, both the parashah and the haftorah teach us not to rely on our own sense of logic, but rather to have faith in the halachic authority as brought down by the Rabbis in each generation. This is the foundation of our legal system and the eternal transmission of Torah. -

Sarah and Hagar by Rev. Dr. Chris Alexander Countryside Community Church June 18, 2017

Nevertheless, She Persisted: Listening to Women of the Bible Week One: Sarah and Hagar by Rev. Dr. Chris Alexander Countryside Community Church June 18, 2017 I. Intentional Listening Scripture: Genesis 16 16Now Sarai, Abram’s wife, bore him no children. She had an Egyptian slave-girl whose name was Hagar, 2and Sarai said to Abram, “You see that the Lord has prevented me from bearing children; go in to my slave-girl; it may be that I shall obtain children by her.” And Abram listened to the voice of Sarai. 3So, after Abram had lived ten years in the land of Canaan, Sarai, Abram’s wife, took Hagar the Egyptian, her slave-girl, and gave her to her husband Abram as a wife.4He went in to Hagar, and she conceived; and when she saw that she had conceived, she looked with contempt on her mistress. 5Then Sarai said to Abram, “May the wrong done to me be on you! I gave my slave- girl to your embrace, and when she saw that she had conceived, she looked on me with contempt. May the Lord judge between you and me!” 6But Abram said to Sarai, “Your slave-girl is in your power; do to her as you please.” Then Sarai dealt harshly with her, and she ran away from her.7The angel of the Lord found her by a spring of water in the wilderness, the spring on the way to Shur. 8And he said, “Hagar, slave-girl of Sarai, where have you come from and where are you going?” She said, “I am running away from my mistress Sarai.” 9The angel of the Lord said to her, “Return to your mistress, and submit to her.”10The angel of the Lord also said to her, “I will so greatly multiply your offspring that they cannot be counted for multitude.” 11And the angel of the Lord said to her, “Now you have conceived and shall bear a son; you shall call him Ishmael, for the Lord has given heed to your affliction. -

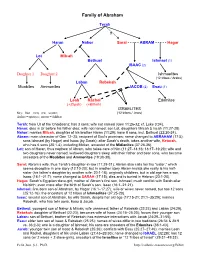

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

"Women Rising" by the Rev. Dr., Renee Wormack-Keels

“Women Rising” Part V of VI in the sermon series “400 years of Africans in America” Genesis 16:1–16 and 21:1–21 The Rev. Dr. Renee Wormack-Keels Guest Minister August 25, 2019 From the Pulpit The First Congregational Church, United Church of Christ 444 East Broad Street, Columbus, OH 43215 Phone: 614.228.1741 Fax: 614.461.1741 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.first-church.org I am honored to be with you today. I am grateful to your pastor, Dr. Tim, for this invitation. It’s a privilege to call him colleague AND friend. This morning, in this sermon series on Race and Racism, I would like to explore a story that does not always get a lot of attention, about a relationship between two women, one man and God. For God is often, if not always, in the midst of our human relationships. “Woman Rising” Genesis 16:1–16 and 21:1–21 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Let’s pray and then we can talk further. God of our weary years. God of our silent tears, God who has brought us safe thus far. Thank you for these moments that are yours and ours to share. Now God, I am standing your promises that you would stand up in me, when I stood up on your behalf. Allow the words of my mouth and the meditations of my heart be acceptable… +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ I won’t read the text from Genesis 16:1–16 and 21:1–21, (but suggest at your leisure sometime, that you read this text, its worthy of at least a 6 week bible study on the several themes) but simply will retell the biblical story of two women, one man and God. -

Graphic Assault

THE BIBLE & CRITICAL THEORY Graphic Assault Reading Sexual Assault and Rape Narratives in Biblical Comics Zanne Domoney-Lyttle, University of Glasgow Abstract The Bible is a foundational document for Western culture, and is both beloved and dangerous, containing stories of hope, love, and justice as well as narratives of abuse, violence, and sexual assault. Stories from the Bible continue to be retold in art, literature, film, theatre, and, more recently, comic books. Comic book Bibles are increasing in popularity yet remain undervalued and understudied , especially their retellings of “texts of terror” which include themes of rape, sexual assault, and gendered violence. In this article, I read the stories of Gen. 16:1-6 (the rape of Hagar by Abraham) and Genesis 34 (the rape of Dinah by Shechem) in two biblical comics, R. Crumb’s Genesis (2009) and Brendan Powell Smith’s The Brick Bible (2011), using the methodological approach of visual criticism. I demonstrate how each creator reinforces androcentric readings of biblical material and fails to take an intersectional approach to their interpretation of the biblical material, resulting in the further silencing of victims of sexual assault and the elevation of their attackers. I then assess the potential impact these graphic retellings may have on their readers, in terms of reinforcing androcentric and hegemonic ideologies in the reader’s own world. Key Words Comic books; biblical reception; visual criticism; gender violence; rape; Dinah; Hagar; Genesis Introduction The Bible is both a beloved and a dangerous document.1 It has the power to offer hope and comfort to victims in pain, yet it contains words that can inflict harm and support dangerous ideologies. -

5774 in a Few Moments I Will Be Offering to Us A

1 RH 1 – 5774 In a few moments I will be offering to us a dvar Torah, a word of Torah commenting on today’s reading – the Story of the expulsion of Hagar. This dvar torah –word of Torah emerges from one of simultaneous avenues of Torah interpretation that are identified by the acronym- PaRDeS–The Orchard. These four levels of interpretation ensure that the Torah doesn’t remain a relic. Our interpretive powers reveal the vibrancy and breadth of the grand mythic structure of our people. As Homer’s writings have become the mythic structure of Western Civilization –the contributions of the grand Jewish myth is considerable in spite of the tension between Athens and Abraham. First we must understand the simple meaning what the Torah text actually says –what do the words mean –Bible scholars at universities around the world engage in this work every day as do Greek scholars continue to pore over Homer’s works to understand its archaic Greek. Pshat- the simple meaning is the P in Pardes – At the same time the reading of the text “hints” at something beyond it –we are somehow nudged by our interaction with the text. This hint is Remez - the R in Pardes If you’re interested in creating a dvar torah – a word of Torah –we delve into the test- we seek in it lessons that will work for us today –this is the source of the commentaries of the Rabbis –midrash –their imaginative reading between the lines of the text. It is also the basis of a drasha- a sermon. -

“The Well” - a Monologue from Hagar // Genesis 16 from Inspired by Rachel Held Evans (Adapted for Length)

“The Well” - a monologue from Hagar // Genesis 16 from Inspired by Rachel Held Evans (adapted for length) Most of the time, God does the naming. Abraham. Isaac. Israel. Just one person in all your sacred Scripture dared to name God, and it wasn’t a priest, prophet, warrior, or king. It was I, Hagar--foreigner, woman, slave. I belonged to a woman blessed with all the things a woman wants--wealth, nobility, beauty--but not the thing a woman in an unsettled territory needs: a womb that can carry a boy. Sarah wore her laugh lines like jewelry. The desert wind sent her white hair dancing and carried her unmistakable peals of laughter through the arid atmosphere like rain. Old and young, men and women, slave and free ventured to her tent for advice on breeding goats, arranging marriages, spicing food, and offering prayers. And yet, in our world, they called this woman barren. I had the misfortune to belong to a woman who believed the wrong name. So she gave my body to Abraham. You will think me callous for not being more angry, more resistant to the charge before me, but bearing the child of a tribal leader, even in another woman’s name, carried with it at least a challenge to my expendability. The moment the old man rolled away from me--I begged the gods of Egypt for a boy. Oh, I begged to every god in every language I knew. A baby’s movements don’t begin as kicks, but as subtle, enigmatic flutters; they don’t tell you that. -

The Expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael (Gen 21:9-21)

The Expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael (Gen 21:9-21) The Expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael (Gen 21:9-21) Aron Pinker [email protected] Abstract: The episode of Hagar and Ishmael’s expulsion is reevaluated within the framework of typical reactions of a scorned woman. If it is assumed that Abraham tried to resolve his marital problems by separating Hagar and Ishmael from his household and settling them with their kin Muzrimites, then most of the textual difficulties are naturally resolved. Even if we interpret the Masoretic Text as an identification of Hagar being an Egyptian, nothing in the text compels us to conclude that she intended to return to Egypt on foot. There is biblical evidence that the relations between Ishmael and Isaac (and, perhaps, Abraham) were not severed. The geography of the region supports continued contact between Abraham, Isaac, Hagar, and Ishmael. Heav’n has no rage like love to hatred turn’d Nor Hell a fury, like a woman scorn’d. William Congreve (1670-1729)1 INTRODUCTION Hagar is mentioned in Genesis 16:1-16, 21:9-21, and 25:12. Of these texts the most problematic is Genesis 21:9-21, which deals with the expulsion of Hagar and Ishmael from Abraham’s household, their travails in the desert, salvation by a divine agent, and settlement in the wilderness of Paran.22 This episode describes events so uncharacteristic to some of the actors that they did not fail to baffle the serious reader of the Masoretic Text since well in the past. Two decades ago Wiesel wrote “Abraham is synonymous with loyalty and abso- lute fidelity; his life a symbol of religious perfection.