An Investigation of Variable Pay Systems in Major League Baseball Mitchell S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relationship Between Kinetics of Countermovement Jump and Proximal Mechanics of Collegiate Baseball Pitching

Louisiana Tech University Louisiana Tech Digital Commons Master's Theses Graduate School Spring 5-2021 Relationship between Kinetics of Countermovement Jump and Proximal Mechanics of Collegiate Baseball Pitching Motoki Sakurai Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.latech.edu/theses Part of the Kinesiology Commons RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN KINETICS OF COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP AND PROXIMAL MECHANICS OF COLLEGIATE BASEBALL PITCHING by Motoki Sakurai, B.S. A Thesis Presented in Parital Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Kinesiology COLLEGE OF EDUCATION LOUISIANA TECH UNIVERSITY May 2021 ABSTRACT Purpose: To identify how countermovement jump (CMJ) kinetics influence kinematics and momentum of the baseball pitching motion with a focus on lower body and proximal movement. Methods: Nineteen Division I collegiate pitchers (age = 19.9 ± 1.5 years; height = 1.86 ± 0.06 m; weight = 90.7 ± 13.8 kg) performed a bilateral CMJ test and threw 5 strike fastballs from the stretch with a slide step on a custom-made pitching mound built for a laboratory setting. A 3D motion capture system tracked whole-body kinematics at 240 Hz from 29 reflective markers. Two force plates recorded ground reaction forces (GRFs) from each leg at 1040 Hz during both jump test and pitching captures. A one-way ANOVA separating high and low fastball velocity groups by an athlete’s median performance identified differences in pitching mechanics and jump kinetic variables. Meaningful differences between the variables were determined by cohen’s d effect size with 95% confidence intervals. The same statistical calculations were repeated to identify differences in pitching mechanics and jump kinetic variables between two groups, split based on the medians of pitchers’ total linear momentum in anterior-posterior direction. -

Baseball Prospects of America 1237 Avenue Z Suite 4P Brooklyn, NY

Baseball Prospects of America 1237 Avenue Z Suite 4P Brooklyn, NY 11235 16 Time C.A.B.A High School World Champions 1988,1992,1993,1994,1995,1996,1998,1999,2000,2002,2003,2004,2005,2007,2008, 2011 Dear Prospect, I will be having my annual top prospects and instructional showcase camp for the Tennessee, Alabama & Georgia areas on Sunday, December 13th, 2020 at Rose Park Athletic Fields located at 1000 Edgehill Ave, Nashville, TN 37203. This camp is for high school players that are interested in playing at the next level, whether collegiate or professionally. All players will receive instruction in hitting, fielding, and pitching from professional scouts and coaches. Steve Bort has 40+ years of coaching & recruiting experience. By attending this camp, Steve can open doors with professional scouts as well as college coaches. The camp director will be New York Mets Area Scout Jarrett England. The camp will be starting at 8:30 A.M. and ending at 1:00 P.M. For additional information please contact Steve Bort at 917-842-1860 and/or visit www.BergenBeachBasebal.com. The total cost of the camp is $190.00. Please make all checks payable to Baseball Prospects of America. Please mail your registration and check immediately as there will be no walkups allowed and the camp will be limited to the first 60 players. The 2019 Bergen Beach National Scout Team roster was filled with some of the top talent from across the United States. We had players with commitments to Missouri, Kentucky, Florida State, Florida, Georgia Tech & Tennessee. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Athens Sandlot League Team Manual For Coaches, Players & Parents ATHENS SANDLOT BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Bill Fournier 590-8659 [email protected] Vice-President Keith McGrath 590-0984 [email protected] Secretary Bob Staron 593-2409 [email protected] Treasurer Kevin Schwarzel 591-1630 [email protected] Legal Counsel George McCarthy 593-3357 [email protected] Player Rep. & Safety Mike Rider 707-3586 [email protected] 2007 SANDLOT COMMISSIONERS 12U Bob Staron 593-2409 [email protected] 12U George McCarthy 593-3357 [email protected] 12U/10U Softball Roger Bissell 591-4002 [email protected] 12U/10U Softball Paul Carey [email protected] 10U Tom Vander Ven 707-7312 [email protected] 10U Trevis Thompson 707-9559 [email protected] 7-8 Kris Kostival 590-2141 [email protected] 7-8 Chris Stewart 591-4605 [email protected] 1 Dear Coaches, Players, and Parents: This Team Manual contains instruction and information for how we would like to see each of the Sandlot teams play baseball. “Team” is the best term to use to describe the type of baseball that we want to teach and encourage our young players to The execute on the field. Another most important word you will hear often is “HUSTLE”. Hustle is the one thing every player can do well, regardless of his/her level of athletic best ability. You might be wondering why we are giving you a team manual for teams ranging in work ages from 7 years old to 12 years old. You may wonder, is this really necessary? We believe so. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, July 1, 2020 * The Boston Globe College lefties drafted by Red Sox have small sample sizes but big hopes Julian McWilliams There was natural anxiety for players entering this year’s Major League Baseball draft. Their 2020 high school or college seasons had been cut short or canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. They lost that chance at increasing their individual stock, and furthermore, the draft had been reduced to just five rounds. Lefthanders Shane Drohan and Jeremy Wu-Yelland felt some of that anxiety. The two were in their junior years of college. Drohan attended Florida State and Wu-Yelland played at the University of Hawaii. There was a chance both could have gone undrafted and thus would have been tasked with the tough decision of signing a free agent deal capped at $20,000 or returning to school for their senior year. “I didn’t know if I was going to get drafted,” Wu-Yelland said in a phone interview. “My agent was kind of telling me that it might happen, it might not. Just be ready for anything.” Said Drohan, “I knew the scouting report on me was I have the stuff to shoot up on draft boards but I haven’t really put it together yet. I felt like I was doing that this year and then once [the season] got shut down, that definitely played into the stress of it, like, ‘Did I show enough?’ ” As it turned out, both players showed enough. The Red Sox selected Wu-Yelland in the fourth round and Drohan in the fifth. -

2021 Topps Tier One Checklist .Xls

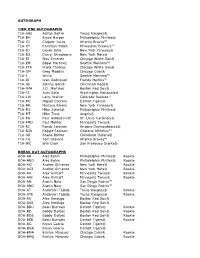

AUTOGRAPH TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS T1A-ABE Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® T1A-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ T1A-CY Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ T1A-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® T1A-DS Darryl Strawberry New York Mets® T1A-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® T1A-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ T1A-FTA Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® T1A-GM Greg Maddux Chicago Cubs® T1A-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ T1A-IR Ivan Rodriguez Florida Marlins™ T1A-JB Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® T1A-JMA J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® T1A-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® T1A-LW Larry Walker Colorado Rockies™ T1A-MC Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® T1A-MR Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® T1A-MS Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-MT Mike Trout Angels® T1A-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® T1A-PMO Paul Molitor Minnesota Twins® T1A-RJ Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® T1A-RJA Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ T1A-SB Shane Bieber Cleveland Indians® T1A-TG Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ T1A-WC Will Clark San Francisco Giants® BREAK OUT AUTOGRAPHS BOA-AB Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-AG Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AGI Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AK Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AKI Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AN Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-ANO Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-AT Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-ATE Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-AV Alex Verdugo Boston -

West Virginia Power Game Notes

WEST VIRGINIA POWER GAME NOTES South Atlantic League - Class-A affiliate of the Seattle Mariners since 2019 - 601 Morris St. Suite 201- Charleston, WV 25301 - 304-344-2287 - www.wvpower.com - Media Contact: David Kahn WEST VIRGINIA POWER (3-3) AT LEXINGTON LEGENDS (2-3) Game: 7 (Road: 7) | April 10, 2019 | Whitaker Bank Ballpark | Lexington, KY Radio: The Jock 1300 and 1340 AM - wvpower.com Airtime: 10:15 A.M. PITCHING MATCHUP RHP Clay Chandler (0-0, 0.00 ERA) vs. RHP Charlie Neuweiler (0-0, 3.60 ERA) Chandler: Allowed two unearned runs over five innings in first start April 5 at GRV Neuweiler: Tossed five innings and gave up two runs on three hits vs. DEL April 4 WEST VIRGINIA BLANKS LEXINGTON TUESDAY: Logan Gilbert dominated in his second career start, tossing CURRENT ROAD TRIP five scoreless innings and ceding just one hit while striking out a career-high nine batters. Meanwhile, West Virginia’s offense provided him with plenty of run support, as the Power claimed a 4-0 win Tuesday evening at Whitaker Bank Record: 3-3 Season High Statistics Ballpark. Gilbert set down the first nine men he faced and only allowed two runners to reach base against him, picking Batting Statistics: Batting: AVG: .206 (43-for-209) AVG: .000 up his first career victory.Onil Pena drove in the team’s first run in the fourth, doubling inJulio Rodriguez, while Cesar AB: 209 AB: 0 Trejo smacked a three-run homer in the sixth to put the game out of reach. David Ellingson and Bryan Pall spun the RISP: 7-for-57 (.123) RISP: 0-for-0 (.000) final four innings, scattering two hits and one walk while striking out five to finish off the Power’s second shutout win. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

15 Robbie Mcclellan #14 Andre Ethier #27 Bryce Kartler

PLAYERS #15 ROBBIE MCCLELLAN #14 ANDRE ETHIER #27 BRYCE KARTLER #10 RODNEY ALLEN #20 NICK WALSH #10 Outfielder RODNEY ALLEN 6-2 • 205 • Jr. • 2V • Bats Right • Throws Right • Culver City, Calif. (Desert Vista HS) **All-America Candidate** **Baseball America Third-Team Preseason All-American** What to Know: Has shown tremendous improvement in defensive skills and will move from left field to center field in 2003…had one of the best offensive performances by a freshman (2001) in school his- tory by hitting .389 with six home runs…strong upper body and good power to all fields…has developed into a line-drive hitter…improved strength and speed with offseason conditioning program…similar build and body to that of Barry Bonds as a Sun Devil…son of a for- mer major league player who grew up around the game…looking to bounce back from a disappointing sophomore season…was named the No. 13 prospect in the Cape Cod League while playing for the Orleans Cardinals with teammate Steve Garrabrants…heads into the season ranked as the No. 46 prospect for the 2003 MLB Draft by Baseball America... named a third-team preseason All-American by Baseball America. 2002 (Sophomore): Finished the year hitting .278 while finishing second on the team with 50 RBI…started 53 games, all coming in left field…had a strong finish to the year, hitting .400 (6x15) with a home run and three RBI in the NCAA Mesa regional…named to the all-tour- nament team for his effort…his solo home run vs. San Diego (5/31) tied the game at 3-3 and eventually led the Devils to the opening- -

PLAY BALL! MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL in BLOOMSBURG Did

PLAY BALL! MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL IN BLOOMSBURG Did you ever dream of seeing major league baseball in Columbia County? It happened once in the past. During the recent American League Divisional Championship series between the New York Yankees and the Detroit Tigers, a few Columbia County long-time baseball fans were reminded of the series played between those same two teams at the Bloomsburg Fair in October 1925. The two major-league teams were scheduled for a three-game series during Fair week. They played on an improvised field on the racetrack infield in front of the grandstand. Each squad brought to town only the bare minimum of players; the Yankee pitchers when they were not on the mound played in the outfield. Two games were completed; the third day’s game was rained out and couldn’t be rescheduled because the teams left town for an engagement in Wilkes-Barre. The Tigers won both games, but both were close, exciting contests. The games were slated at 10:00am each day so as not to conflict with the trotting races held in the afternoons. Apparently, the Fair Board was hoping that the major leaguers would draw folks to the Fair in the usually-slack morning hours. And the scheme worked – the games drew upwards of 10,000 fans each day. At the time, the grandstand capacity was only 2,000, so the other fans crowded the railing around the oval track. In 1925 the Yankees were in the middle of their storied 1920s championship era. With Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig as mainstays, this was arguably the greatest baseball team ever assembled. -

Class 2 - the 2004 Red Sox - Agenda

The 2004 Red Sox Class 2 - The 2004 Red Sox - Agenda 1. The Red Sox 1902- 2000 2. The Fans, the Feud, the Curse 3. 2001 - The New Ownership 4. 2004 American League Championship Series (ALCS) 5. The 2004 World Series The Boston Red Sox Winning Percentage By Decade 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 .522 .572 .375 .483 .563 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 .510 .486 .528 .553 .521 2001-10 11-17 Total .594 .549 .521 Red Sox Title Flags by Decades 1901-1910 11-20 21-30 31-40 41-50 1 WS/2 Pnt 4 WS/4 Pnt 0 0 1 Pnt 1951-1960 61-70 71-80 81-90 91-00 0 1 Pnt 1 Pnt 1 Pnt/1 Div 1 Div 2001-10 11-17 Total 2 WS/2 Pnt 1 WS/1 Pnt/2 Div 8 WS/13 Pnt/4 Div The Most Successful Team in Baseball 1903-1919 • Five World Series Champions (1903/12/15/16/18) • One Pennant in 04 (but the NL refused to play Cy Young Joe Wood them in the WS) • Very good attendance Babe Ruth • A state of the art Tris stadium Speaker Harry Hooper Harry Frazee Red Sox Owner - Nov 1916 – July 1923 • Frazee was an ambitious Theater owner, Promoter, and Producer • Bought the Sox/Fenway for $1M in 1916 • The deal was not vetted with AL Commissioner Ban Johnson • Led to a split among AL Owners Fenway Park – 1912 – Inaugural Season Ban Johnson Charles Comiskey Jacob Ruppert Harry Frazee American Chicago NY Yankees Boston League White Sox Owner Red Sox Commissioner Owner Owner The Ruth Trade Sold to the Yankees Dec 1919 • Ruth no longer wanted to pitch • Was a problem player – drinking / leave the team • Ruth was holding out to double his salary • Frazee had a cash flow crunch between his businesses • He needed to pay the mortgage on Fenway Park • Frazee had two trade options: • White Sox – Joe Jackson and $60K • Yankees - $100K with a $300K second mortgage Frazee’s Fire Sale of the Red Sox 1919-1923 • Sells 8 players (all starters, and 3 HOF) to Yankees for over $450K • The Yankees created a dynasty from the trading relationship • Trades/sells his entire starting team within 3 years. -

At Villanova. the Program's First Year Of

ATHLETICS ADMINISTRATION ~ QUICK FACTS COVERS ABOUT VILLANOVA 2008 Senior Class . Front and Back Covers Location . .Villanova, Pa. 2007 BIG EAST Tournament . Inside Front Cover Enrollment . .6,240 Glimpse of Villanova . Inside Back Cover Founded . .1842 2008 Schedule . Back Cover President . .Rev. Peter M. Donohue, O.S.A. 2008 SEASON Nickname . .Wildcats Athletics Administration/Quick Facts. 1 Colors . .Blue (PMS 281) and White Roster . 2 Affiliation . .NCAA Division I Season Outlook . 3-4 Conference . .BIG EAST/National Division Head Coach Joe Godri . 5 Assistant Coaches Matt Kirby, Rod Johnson, Chris Madonna. 6 COACHING STAFF Meet the Wildcats . 7-16 Head Coach . .Joe Godri ‘96 VILLANOVA BASEBALL IS... Alma Mater . (New Mexico State ) Record at Villanova . .159-148-3, .518 (6 Years) Tradition . 17 Career Record . .Same Success . 18 Pitching Coach/Recruiting Coordinator . .Matt Kirby (2nd Season) A Regional Power . 19 Third Base Coach/Infield Coach . .Rod Johnson (7th Season) PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS Hitting Coach . .Chris Madonna (1st Season) Villanova Baseball in the Professional Ranks . 20 Baseball Office . .610-519-4529 Wildcats in the Major Leagues . 21 Head Coach E-Mail . [email protected] Villanova Baseball and the Major League Draft . 22 Assistant Coach E-Mail . [email protected] Villanova Ballpark at Plymouth . 23 BIG EAST Conference . 24 HOME GAMES 2007 YEAR IN REVIEW Stadium . .Villanova Ballpark at Plymouth Accomplishments/Overall Results . 25 Location . .Plymouth Meeting, Pa. (15 minutes from campus) Statistics . 26 Capacity . .750 TEAM HISTORY Surface . .Grass BIG EAST Championship History . 27 Dimensions . .330 LF, 370 LC, 405 CF, 370 RC, 330 RF Postseason History/Head Coaches/Year-by-Year Record. -

“As He Sees It”

“Baseball took my sight away, but it gave me Phone: (973) 275-2378 / [email protected] a life,” - Ed Lucas Ed Lucas – A Biography In Brief… “As He Sees It” Lucas, a native of New Jersey attended college at Seton Hall University (’62) and upon graduation was An Exhibit on the able to parlay his love of baseball into a lifelong career Extraordinary Life & Accomplishments as a freelance baseball reporter who has interviewed of Expert Baseball Reporter… countless baseball players, administrators and personalities over the last five decades. His work and Ed Lucas accomplishments have been lauded in many ways either through countless by-lines, or as the featured subject in various media accounts. For more A Biographical & Baseball-Oriented information about Ed Lucas please consult the Retrospective remainder of this brochure along with Ron Bechtel’s recent article – “For The Love Of The Game” (Seton Hall University Magazine, 26-29, Winter/Spring 2007) and featured homepage – http://www.edlucas.org “As He Sees It” An Exhibit on the Extraordinary Life & Accomplishments of Expert Baseball Reporter… Ed Lucas Special Thanks To… Jeannie Brasile, Director of the Walsh Library Gallery Jason Marquis, Volunteer Walsh Library Gallery Window Exhibit G. Gregory Tobin, Author & Reference Source Dr. Howard McGinn, Dean of University Libraries Sponsored By The For More Information Please Contact… Msgr. William Noé Field Archives & Alan Delozier, University Archivist & Exhibit Curator Special Collections Center would ultimately secure in later years in such periodicals as Baseball Digest, New York Times, Newark Star-Ledger, Sports Illustrated and even the book – “Bronx Zoo” by Sparky Lyle.