Exploring Jane Fonda's New Femininity in Grace and Frankie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

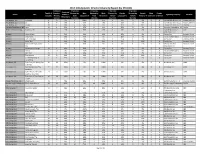

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Emmy Nominations

69th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 13, 2017 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Noms to date Previous Wins to Category Nominee Program Network 69th Emmy Noms Total (across all date (across all categories) categories) LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Viola Davis How To Get Away With Murder ABC 1 3 1 Claire Foy The Crown Netflix 1 1 NA Elisabeth Moss The Handmaid's Tale Hulu 1 8 0 Keri Russell The Americans FX Networks 1 2 0 Evan Rachel Wood Westworld HBO 1 2 0 Robin Wright House Of Cards Netflix 1 6 0 LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Sterling K. Brown This Is Us NBC 1 2 1 Anthony Hopkins Westworld HBO 1 5 2 Bob Odenkirk Better Call Saul AMC 1 11 2 Matthew Rhys The Americans FX Networks 2* 3 0 Liev Schreiber Ray Donovan Showtime 3* 6 0 Kevin Spacey House Of Cards Netflix 1 11 0 Milo Ventimiglia This Is Us NBC 1 1 NA * NOTE: Matthew Rhys is also nominated for Guest Actor In A Comedy Series for Girls * NOTE: Liev Schreiber also nominamted twice as Narrator for Muhammad Ali: Only One and Uconn: The March To Madness LEAD ACTRESS IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Carrie Coon Fargo FX Networks 1 1 NA Felicity Huffman American Crime ABC 1 5 1 Nicole Kidman Big Little Lies HBO 1 2 0 Jessica Lange FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 8 3 Susan Sarandon FEUD: Bette And Joan FX Networks 1 5 0 Reese Witherspoon Big Little Lies HBO 1 1 NA LEAD ACTOR IN A LIMITED SERIES OR A MOVIE Riz Ahmed The Night Of HBO 2* 2 NA Benedict Cumberbatch Sherlock: The Lying Detective (Masterpiece) PBS 1 5 1 -

Grace and Frankie E a Sexualidade Feminina Na Velhice NAYARA HELOU CHUBACI GÜÉRCIO1

III INTERPROGRAMAS – XVI SECOMUNICA DIVERSIDADE E ADVERSIDADES: O INCOMUM NA COMUNICAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE BRASÍLIA - BRASÍLIA, DF - 21 e 22/09/2017. grace and frankie e a sexualidade feminina na velhice NAYARA HELOU CHUBACI GÜÉRCIO1 Resumo Sob a perspectiva da interseccionalidade, neste artigo, pretendeu-se cruzar as temáticas de gênero, velhice e sexualidade dentro da narrativa seriada. A série exibida pela plataforma de streaming Ne- tflix, Grace and Frankie, é o objeto deste estudo, por ser um relevante exemplo de subversão das concepções biunívocas acerca da imagem da idosa urbana e ocidental. A metodologia empregada é a análise fílmica e o método utilizado é o proposto por Casseti e Di Chio (1998). A categoria analítica selecionada para este estudo foi “insegurança x autoconfiança”. A redescoberta da sexualidade faz parte da reinvenção feminina na velhice e é tratada de maneira honesta e contestadora pelo seriado. Palavras-chave: Velhice; Sexualidade; Gênero; Grace and Frankie; Série de televisão. 1. Velhice Feminina e Sexualidade Muitos são os tensionamentos científicos existentes entre “envelhecimento ativo” versus dete- rioramento físico, bem como entre trabalho e aposentadoria. O bem-estar na velhice é frequentemente discutido no contexto da dieta, do controle hormonal, dos exercícios físicos e da capacidade laboral e reprodutiva. Estas preocupações acadêmicas, no entanto, raramente escapam aos moldes do patriar- cado e do preconceito etário em que, por exemplo, a sexualidade na velhice — principalmente, na finitude2 das mulheres — é inexistente ou um fator a ser desconsiderado. Teresa de Lauretis, em “A tecnologia do gênero” (1994), discorre sobre a tese de que os estu- dos de gênero, por essência, se respaldam na construção por meio da desconstrução. -

70Th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 12, 2018 (A Complete List of Nominations, Supplemental Facts and Figures May Be Found at Emmys.Com)

70th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 12, 2018 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Nominations Previous Wins 70th Emmy Nominee Program Network to date to date Nominations Total (across all categories) (across all categories) LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Claire Foy The Crown Netflix 1 2 0 Tatiana Maslany Orphan Black BBC America 1 3 1 Elisabeth Moss The Handmaid's Tale Hulu 1 10 2 Sandra Oh Killing Eve BBC America 1 6 0 Keri Russell The Americans FX Networks 1 3 0 Evan Rachel Wood Westworld HBO 1 3 0 LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Jason Bateman Ozark Netflix 2* 4 0 Sterling K. Brown This Is Us NBC 2* 4 2 Ed Harris Westworld HBO 1 3 0 Matthew Rhys The Americans FX Networks 1 4 0 Milo Ventimiglia This Is Us NBC 1 2 0 Jeffrey Wright Westworld HBO 1 3 1 * NOTE: Jason Bateman also nominated for Directing for Ozark * NOTE: Sterling K. Brown also nominated for Guest Actor in a Comedy Series for Brooklyn Nine-Nine LEAD ACTRESS IN A COMEDY SERIES Pamela Adlon Better Things FX Networks 1 7 1 Rachel Brosnahan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Prime Video 1 2 0 Allison Janney Mom CBS 1 14 7 Issa Rae Insecure HBO 1 1 NA Tracee Ellis Ross black-ish ABC 1 3 0 Lily Tomlin Grace And Frankie Netflix 1 25 6 LEAD ACTOR IN A COMEDY SERIES Anthony Anderson black-ish ABC 1 6 0 Ted Danson The Good Place NBC 1 16 2 Larry David Curb Your Enthusiasm HBO 1 26 2 Donald Glover Atlanta FX Networks 4* 8 2 Bill Hader Barry HBO 4* 14 1 William H. -

From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie ………………………………………………………………………………………………………

HyperCultura Biannual Journal of the Department of Letters and Foreign Languages, Hyperion University, Romania Electronic ISSN: 2559 – 2025; ISSN-L 2285 – 2115 OPEN ACCESS Vol 7/ 201 8 Issue Editor: Sorina Georgescu ....................................................................................................... Rocío Palomeque Recio Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Recommended Citation: Recio, Rocío Palomeque. “Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie .” HyperCultura 7 (2018) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. http://litere.hyperion.ro/hypercultura/ License: CC BY 4.0 Received: 30 August 2018/ Accepted: 18 February 2019/ Published: 31 March 2019 No conflict of interest Rocío Palomeque Recio, “Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie.” Rocío Palomeque Recio Nottingham Trent University Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie Abstract: The purpose of this work is to perform a comparative analysis of how women’s sexuality is displayed in both the American TV show Grace and Frankie (2015-present) and The Golden Girls (1985-1992) using a post- feminist optic (Genz and Brabon 2018). The post-feminist rhetoric, which surged as a result of the economic boom of the 1990s and 2000s, optimistically embraces consumer freedom, choice and empowerment (Genz and Brabon 2018) and presents women as assertive beings who enjoy their sexual freedom and financial agency. Analyzing two shows that feature senior women as their main characters , whose pilot episodes aired thirty years apart can shed some light on how media have changed the portrayal of senior women and their sexualities. The Golden Girls and Grace and Frankie share enough features to enable us to trace similarities: the leading characters are all white women, middle-upper class American, for instance. -

Baron Vaughn – Comedian, Actor, Regular on Netflix Series Grace and Frankie

Baron Vaughn – comedian, actor, regular on Netflix series Grace and Frankie Other shows that Baron Vaughn has been in include the t-v shows Law and Order and Girls. He’s also the voice of Tom Servo on the upcoming re-boot of Mystery Science Theater 3000. Baron’s story begins in a place not widely known as a comedy hot spot. “This is in a little town called Tucumcari, New Mexico. It’s on Route 66, America’s main street. It was the actual main street of Tucumcari.” That’s where he grew up. He was raised by his great grandparents. For him, that’s where comedy started. “They were the people I loved and the people I looked up to. There were t-v shows they watched that made them laugh. At the end of the 70’s and early 80’s there was a glut of sitcoms featuring black people like The Jefferson’s, Good Times and Sanford and Son. They also watched Nick at Night. Shows like Dobie Gillis, Patty Duke and Mr. Ed. The first time I saw Sammy Davis Junior on Patty Duke, I had to react the exact same way that black people in the 60’s reacted: ‘We’re on t-v, we made it!’ I watched all of that stuff and was soaking it in and observed the laughter from my parental figures and I was like ‘Oh, I can get them to do that.’ That’s when I saw that I had some power and some value. I could make them laugh as hard as all the t-v shows they were watching and loved.” Baron moved to Las Vegas with his Mom when he as around eight. -

Facts & Figures

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2020 NOMINATIONS as of August 12, 2020 includes producer nominations 72nd EMMY AWARDS updated 08.12.2020 version 1 Page 1 of 24 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2019 Game Of Thrones - 12 Chernobyl - 10 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 8 Free Solo – 7 Fleabag - 6 Love, Death & Robots - 5 Saturday Night Live – 5 Fosse/Verdon – 4 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver – 4 Queer Eye - 4 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 4 Age Of Sail - 3 Barry - 3 Russian Doll - 3 State Of The Union – 3 The Handmaid’s Tale – 3 Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown – 2 Bandersnatch (Black Mirror) - 2 Crazy Ex-Girlfriend – 2 Our Planet – 2 Ozark – 2 RENT – 2 Succession - 2 United Shades Of America With W. Kamau Bell – 2 When They See Us – 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2019 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Fleabag Drama Series: Game Of Thrones Limited Series: Chernobyl Television Movie: Bandersnatch (Black Mirror) Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Phoebe Waller-Bridge (Fleabag) Lead Actor: Bill Hader (Barry) Supporting Actress: Alex Borstein (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel) Supporting Actor: Tony Shalhoub (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Jodie Comer (Killing Eve) Lead Actor: Billy Porter (Pose) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Peter Dinklage (Game Of Thrones) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) Lead Actor: Jharrel Jerome (When They See Us) Supporting -

GRACE and FRANKIE

! ! ! ! ! ! ! GRACE and FRANKIE EP. 113 Written by Marta Kauffman & Howard J. Morris & Alexa Junge Directed by Dean Parisot ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! PRODUCTION WHITE 11/10/14 (Pgs. 33) PRODUCTION BLUE (FULL) 11/13/14 (Pgs. 32) PRODUCTION PINK (PAGES) 11/14/14 (Pgs. 2,7,7A,15,15A,28,29,30,31,31A) PRODUCTION YELLOW (PAGES) 11/16/14 (Pgs. 28-31,31A,31B,32) PRODUCTION GREEN (PAGES) 11/17/14 (Pgs. 1,2,3,4) FINAL: PRODUCTION GOLDENROD 11/18/14 (Pgs.32) © 2014 SKYDANCE PRODUCTIONS, LLC All Rights Reserved No portion of this script may be performed, or reproduced by any means, or quoted, or published in any medium without prior written consent of SKYDANCE PRODUCTIONS, LLC. * 5555 Melrose Avenue * Los Angeles, CA 90038 * GRACE and FRANKIE EP. 113 PRODUCTION GOLDENROD 11/18/14 CAST LIST GRACE............................................JANE FONDA FRANKIE.........................................LILY TOMLIN ROBERT.........................................MARTIN SHEEN SOL...........................................SAM WATERSTON BRIANNA..................................JUNE DIANE RAPHAEL BUD............................................BARON VAUGHN COYOTE..........................................ETHAN EMBRY MALLORY.....................................BROOKLYN DECKER GUY.........................................CRAIG T. NELSON GRACE and FRANKIE EP. 113 PRODUCTION BLUE 11/13/14 SET LIST INTERIORS EXTERIORS BEACH HOUSE BEACH Kitchen Kitchen/Family Room ROBERT & SOL’S HOUSE Living Room ROBERT & SOL’S HOUSE Dining Room Living Room FRANKIE & SOL’S HOUSE Bedroom GRACE AND FRANKIE EP 113 PROD GREEN 11/17/14 GRACE AND FRANKIE Episode 113 FADE IN: 1 INT. BEACH HOUSE - STUDIO - NIGHT - (N1) * 1 FRANKIE, in her painting regalia, is lying on her couch, eyes * closed. A troubled GRACE, in her robe, pops her head in and * sees Frankie seemingly asleep on the couch. A little * disappointed, Grace turns around to leave. -

Mapping the Landscape of Social Impact Entertainment

Bonnie Abaunza Neal Baer Diana Barrett Peter Bisanz Dustin Lance Black Johanna Blakley Caty Borum Chattoo Don Cheadle Wendy Cohen Nonny de la Peña Leonardo DiCaprio Geralyn Dreyfous Kathy Eldon Eve Ensler Oskar Eustis Mapping the landscape of Shirley Jo Finney social impact entertainment Beadie Finzi Terry George Holly Gordon Sandy Herz Reginald Hudlin Darnell Hunt Shamil Idriss Tabitha Jackson Miura Kite Michelle Kydd Lee Anthony Leiserowitz David Linde Tom McCarthy Cara Mertes Sean Metzger Pat Mitchell Shabnam Mogharabi Joshua Oppenheimer Elise Pearlstein Richard Ray Perez Gina Prince-Bythewood Ana-Christina Ramón James Redford Liba Wenig Rubenstein Edward Schiappa Cathy Schulman Teri Schwartz Ellen Scott Jess Search Fisher Stevens Carole Tomko Natalie Tran Amy Eldon Turteltaub Gus Van Sant Rainn Wilson Samantha Wright Welcome to the test — a major university research SIE’s work to date: the most effective Welcome center focused on the power of strategies for driving impact through entertainment and performing arts to storytelling; the question of when, inspire social impact. The structure of within the creative process, impact Note this new center would be built upon three should first be considered; the key role pillars: research, education and special of research to explore, contextualize initiatives, and public engagement, and help define the field; and the programming and exhibition. importance of partnering with the right allies across the entertainment At the time, there wasn’t a university and performing arts industries for new model fully focused on this topic that ideas, special projects and initiatives. I could draw upon for information as the field was in its infancy. -

Title # of Eps. # Episodes Male Caucasian % Episodes Male

2020 DGA Episodic TV Director Inclusion Report (BY SHOW TITLE) # Episodes % Episodes # Episodes % Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # of % Episodes % Episodes % Episodes % Episodes Male Male Female Female Title Male Males of Female Females of Network Studio / Production Co. Eps. Male Caucasian Males of Color Female Caucasian Females of Color Unknown/ Unknown/ Unknown/ Unknown/ Caucasian Color Caucasian Color Unreported Unreported Unreported Unreported 100, The 12 6.0 50.0% 2.0 16.7% 3.0 25.0% 1.0 8.3% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% CW Warner Bros Companies Paramount Pictures 13 Reasons Why 10 6.0 60.0% 2.0 20.0% 2.0 20.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Netflix Corporation Paramount 68 Whiskey 10 7.0 70.0% 0.0 0.0% 3.0 30.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Network CBS Companies 9-1-1 18 4.0 22.2% 6.0 33.3% 5.0 27.8% 3.0 16.7% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% FOX Disney/ABC Companies 9-1-1: Lone Star 10 5.0 50.0% 2.0 20.0% 3.0 30.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% FOX Disney/ABC Companies Absentia 6 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 6.0 100.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Amazon Sony Companies Alexa & Katie 16 3.0 18.8% 3.0 18.8% 5.0 31.3% 5.0 31.3% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% Netflix Netflix Alienist: Angel of Darkness, Paramount Pictures The 8 5.0 62.5% 0.0 0.0% 3.0 37.5% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% TNT Corporation All American 16 4.0 25.0% 8.0 50.0% 2.0 12.5% 2.0 12.5% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% CW Warner Bros Companies All Rise 20 10.0 50.0% 2.0 10.0% 5.0 25.0% 3.0 15.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% CBS Warner Bros Companies Almost Family 12 6.0 50.0% 0.0 0.0% 3.0 25.0% 3.0 25.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% FOX NBC Universal Electric Global Almost Paradise 3 3.0 100.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% 0.0 0.0% WGN America Holdings, Inc.