Visions Fugitives Music for Strings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Discussion of the Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op

A DISCUSSION OF THE PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN D MINOR, OP. 14, BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV A PAPER ACCOMPANYING A THREE CREDIT-HOUR CREATIVE PROJECT RECITAL SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC BY QINYUAN LIN DR. ROBERT PALMER‐ ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 Preface The goal of this paper is to introduce the piece, provide historical background, and focus on the musical analysis of the sonata. The introduction of the piece will include a brief biography of Sergei Prokofiev and the circumstance in which the piece was composed. A general overview of the composition, performance, and perception of this piece will be discussed. The bulk of the paper will focus on the musical analysis of Piano Sonata No. 2 from my perspective as a performer of the piece. It will be broken into four sections, one each for the four movements in the sonata. In the discussion for each movement, I will analyze the forms used as well as required techniques and difficulties to be considered by the pianist. The conclusion will summarize the discussion. i Table of Contents Preface ________________________________________________________________ i Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 The First Movement: Allegro, ma non troppo __________________________________ 5 The Second Movement: Scherzo ____________________________________________ 9 The Third Movement: Andante ____________________________________________ 11 The Fourth Movement: Vivace ____________________________________________ 13 Conclusion ____________________________________________________________ 17 Bibliography __________________________________________________________ 18 ii Introduction Sergei Prokofiev was born in 1891 to parents Sergey and Mariya and grew up in comfortable circumstances. His mother, Mariya, had a feeling for the arts and gave the young Prokofiev his first piano lessons at the age of four. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College A

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A PEDAGOGICAL AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO PROKOFIEV’S FOUR PIECES, OP. 32 A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By IVAN D. HURD III Norman, Oklahoma 2017 A PEDAGOGICAL AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO PROKOFIEV’S FOUR PIECES, OP. 32 A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Jane Magrath, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Barbara Fast ______________________________ Dr. Jeongwon Ham ______________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon ______________________________ Dr. Caleb Fulton Dr. Click here to enter text. © Copyright by IVAN D. HURD III 2017 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The number of people that deserve recognition for their role in completing not only this document, but all of my formal music training and education, are innumerable. Thank you to the faculty members, past and present, who have served on my doctoral committee: Dr. Jane Magrath (chair), Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Jeongwon Ham, Dr. Paula Conlon, Dr. Rachel Lumsden, and Dr. Caleb Fulton. Dr. Magrath, thank you for inspiring me, by your example, to find the absolute best possible version of myself as a pianist, educator, collaborator, writer, and scholar. I am incredibly grateful to have had the opportunity to study with you on a weekly basis in lessons, to develop and hone my teaching skills through your guidance in pedagogy classes and observed lessons, and for your encouragement throughout every aspect of the degree. Dr. Fast, I especially appreciate long conversations about group teaching, your inspiration to try new things and be creative in the classroom, and for your practical career advice. -

Freedom in Interpretation and Piano Sonata No. 7 by Sergei Prokofiev

Freedom in Interpretation and Piano Sonata No. 7 by Sergei Prokofiev -A comparison of two approaches to piano interpretation- Nikola Marković Supervisor Knut Tønsberg This Master’s Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, 2012. Faculty of Fine Arts Department of Music Table of Contents ABSTRACT............................................................................................................................5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................5 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................6 1.1 About the topic........................................................................................................6 1.2 Research question and aim for the project ............................................................6 1.3 Methods..................................................................................................................7 1.4 Structure of the thesis.............................................................................................8 2 The composer, the performers and what lies between....................................................9 2.1 Prokofiev – life and creation...................................................................................9 -

A Study of Selected Piano Toccatas in the Twentieth Century: a Performance Guide Seon Hwa Song

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Study of Selected Piano Toccatas in the Twentieth Century: A Performance Guide Seon Hwa Song Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC A STUDY OF SELECTED PIANO TOCCATAS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By SEON HWA SONG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Seon Hwa Song defended on January 12, 2011. _________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo Professor Directing Treatise _________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative _________________________ Douglas Fisher Committee Member _________________________ Gregory Sauer Committee Member Approved: _________________________________ Leonard Mastrogiacomo, Professor and Coordinator of Keyboard Area _____________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Above all, I am eagerly grateful to God who let me meet precious people: great teachers, kind friends, and good mentors. With my immense admiration, I would like to express gratitude to my major professor Leonard Mastrogiacomo for his untiring encouragement and effort during my years of doctoral studies. His generosity and full support made me complete this degree. He has been a model of the ideal teacher who guides students with deep heart. Special thanks to my former teacher, Dr. Karyl Louwenaar for her inspiration and warm support. She led me in my first steps at Florida State University, and by sharing her faith in life has sustained my confidence in music. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

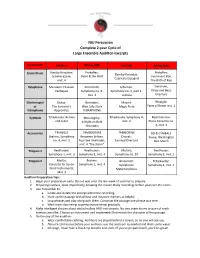

NIU Percussion Complete 2‐Year Cycle of Large Ensemble Audi On

NIU Percussion Complete 2‐year Cycle of Large Ensemble Audion Excerpts Instrument Fall Even Spring Odd Fall Odd Spring Even Rimsky‐Korsakov: Prokofiev: Prokofiev: Snare Drum Rimsky‐Korsakov: Scheherazade, Peter & the Wolf Lieutenant Kijé, Capriccio Espagnol mvt. 4 The Birth of Kijé Xylophone Messiaen: Oiseaux Persiche, Schuman: Gershwin, Exoques Symphony no. 6, Symphony no. 3, part 2, Porgy and Bess, mvt. 4 toccata Overture Glockenspiel Dukas: Bernstein, Mozart: Respighi: or The Sorcerer’s West Side Story Magic Flute Pines of Rome mvt. 1 Vibraphone Apprence VIBRAPHONE Cymbals Tchaikovsky: Romeo Mussorgsky: Tchaikovsky: Symphony 4, Rachmaninov: and Juliet A Night on Bald mvt. 4 Piano Concerto no. Mountain 2, mvt. 3 Accessories TRIANGLE TAMBOURINE TAMBORINE BD & CYMBALS Brahms, Symphony Benjamin Brien: Dvorak: Sousa, Washington no. 4, mvt. 3 Four Sea Interludes, Carnival Overture Post March mvt. 4 “the storm” Timpani 1 Beethoven: Beethoven: Mozart, Beethoven: Symphony 1, mvt. 3 Symphony 9, mvt. 4 Symphony no. 39 Symphony 9, mvt. 1 Timpani 2 Marn, Brahms: Hindemith: Tchaikovsky: Concerto for Seven Symphony 1, mvt. 4 Symphonic Symphony 4, mvt. 1 Wind Instruments, Metamorphosis Mvt. 3 Audion Preparaon Tips: 1. Begin your preparaon early. Do not wait unl the last week of summer to prepare. 2. Preparing involves, most importantly, knowing the music! Study recordings before you learn the notes. 3. Use Transcribe! to: a. locate and isolate the excerpt within the recording. b. mark up the passage with phrase and measure markers as helpful. c. loop phrases and play along with them. Construct the passage one phrase at a me. d. Work from slow tempi to performance tempi gradually. -

Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 50 in C Minor

Second PhD Presentation Topic: Intertextuality and Narrativity in Medtner’s Toccata: Piano Concerto No. 2, op. 50 in C minor (1880-1951) John Zachariah Diutlwileng Ntsepe Scholarly Doctoral Programme (PhD) University of Music and Performing Arts, Graz (KUG) Advisors: Prof. Christian Utz Prof. Peter Revers Prof. Christian Flamm 17 January 2020 SECOND PRESENTATION Introduction In my first presentation, I introduced the topic of my thesis: Investigating Nikolai Medtner’s Piano Concertos. Medtner’s sonatas and concertos form an imperative part of his oeuvre. The core of my dissertation is delineated to his three piano concertos. Medtner’s dual cultural heritage (Russian and German) is highlighted by influences from composers such as Beethoven, Chopin, Grieg, Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Schubert, Schumann, Scriabin, Tchaikovsky and Wagner, including poets such as Fet, Geothe, Heine, Lermantov, Nietzeche, Pushkin and Tyutchev. Christoph Flamm (1995: 69) also stresses Medtner’s mutually beneficial friendship with the Symbolist poet and theorist, Andrei Bely. Even though Medtner was mostly auto-didactical, shortly after his graduation (around the beginning of 1901) Medtner had consultations and discussions regarding form and structural problems with Sergej Taneev (Flamm 1995:5). However, Medtner’s natural talent provided him with original and individual strategies for overcoming formal and structural conundrums in his concertos. Moreover, due to their multiple illusions and references to other musical and literary works, Medtner’s concertos require -

Download Booklet

572318bk Prokofiev:570034bk Hasse 22/5/11 9:33 PM Page 4 Matthew Jones Matthew is violist of the Bridge Duo (with pianist Michael Hampton) and the Debussy Ensemble. Recent recital and chamber music venues include the Wigmore Hall, London’s South Bank and the Forbidden City Concert Hall in Beijing; he made his Carnegie Hall recital debut in 2008. He was also a member of the Badke String Quartet when they won the 2007 Melbourne International Chamber Music Competition, and performs regularly with Ensemble MidtVest in Denmark. He is greatly in demand as a concerto soloist, festival artist and contemporary music performer. Matthew is a professor at Trinity College of Music, Royal Welsh College and Charterhouse International Music Festival, PROKOFIEV and has given masterclasses in the USA, Australia, Malaysia, Japan and throughout Europe. His extensive discography includes two Bridge Duo recordings of English music, Hilary Tann’s chamber music and Haflidi Hallgrimsson’s chamber works. Born in Swansea, Wales, Matthew is also a composer, conductor, mathematics graduate and Suite from teacher of the Alexander Technique and Kundalini Yoga. For more information, visit www.matt-jones.com. Rivka Golani Romeo and Rivka Golani is recognized as one of the great violists and musicians of modern times. BBC Music Magazine included her in its list of the 200 most important instrumentalists and the five most important violists currently performing. Her contributions to the Juliet advancement of viola technique have already given her a place in the history of the instrument and have been a source of inspiration not only to other players but to many composers who have been motivated by her mastery: more than 215 works have been (arr. -

Cipc-2021-Program-Notes.Pdf

PROGRAM NOTES First and Second Rounds Written by musicologists Marissa Glynias Moore, PhD, Executive Director of Piano Cleveland (MGM) and Anna M. O’Connell (AMO) Composer Index BACH 03 LISZT 51 BÁRTOK 07 MESSIAEN 57 BEACH 10 MONK 59 BEETHOVEN 12 MOZART 61 BRAHMS 18 RACHMANINOFF 64 CHOPIN 21 RAMEAU 69 CZERNY 29 RAVEL 71 DEBUSSY 31 PROKOFIEV 74 DOHNÁNYI 34 SAINT-SAËNS 77 FALLA 36 SCARLATTI 79 GRANADOS 38 SCHUBERT 82 GUARNIERI 40 SCRIABIN 84 HAMELIN 42 STRAVINSKY 87 HANDEL 44 TANEYEV 90 HAYDN 46 TCHAIKOVSKY/FEINBERG 92 LIEBERMANN 49 VINE 94 2 2021 CLEVELAND INTERNATIONAL PIANO COMPETITION / PROGRAM NOTES he German composer Johann Sebastian Bach was one of a massive musical family of Bachs whose musical prowess stretched over two Johann Thundred years. J.S. Bach became a musician, earning the coveted role as Thomaskantor (the cantor/music director) for the Lutheran church Sebastian of St. Thomas in Leipzig. At St. Thomas, Bach composed cantatas for just about every major church holiday, featuring a variety of different voice types Bach and instruments, and from which his famed chorales are sung to this day in churches and choral productions. As an organist, he was well known for his ability to improvise extensively on hymn (chorale) tunes, and for reharmonizing (1685-1750) older melodies to fit his Baroque aesthetic. Many of these tunes also remain recognizable in church hymnals. Just as his chorales serve as a basis in composition technique for young musicians today, his collection of keyboard works entitled The Well-Tempered Clavier serves even now as an introduction to preludes and fugues for students of the piano. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, December 18, 2014, at 8:00 Friday, December 19, 2014, at 1:30 Saturday, December 20, 2014, at 8:00 Carlos Miguel Prieto Conductor Cynthia Yeh Percussion Prokofiev Suite from Lieutenant Kijé, Op. 60 The Birth of Kijé Romance Kijé’s Wedding Troika The Burial of Kijé MacMillan Veni, Veni, Emmanuel CYNTHIA YEH First Chicago Symphony Orchestra subscription concert performances INTERMISSION Revueltas Sensemayá First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra Intrada Capriccio, Notturno and Arioso Passacaglia, Toccata and Chorale The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is grateful to 93XRT and RedEye for their generous support as media sponsors of the Classic Encounter series. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by PhillipDaniel HuscherJaffé and Phillip Huscher Sergei Prokofiev Born April 23, 1891, Sontsovka, Ukraine. Died March 5, 1953, Moscow. Suite from Lieutenant Kijé, Op. 60 Prokofiev’s first film would find it hard to coordinate with the score, written in 1933 for Leningrad studio to meet production deadlines. one of the earliest Soviet Furthermore, for much of the 1920s, he had sound features, is today cultivated a dissonant style with such modernist one of the most celebrated works as the Second Symphony and the Quintet, of that era (more famous and Prokofiev was seen in some quarters as than, say, Max Steiner’s politically suspect: when his “Soviet” ballet Le almost contemporary pas d’acier had been auditioned by Moscow’s King Kong score). -

A Study of Js Bach's Toccata Bwv 916; L. Van Beethoven's Sonata

A STUDY OF J. S. BACH’S TOCCATA BWV 916; L. VAN BEETHOVEN’S SONATA OP. 31, NO. 3; F. CHOPIN’S BALLADE, OP. 52; L. JANÁČEK’S IN THE MISTS: I, III; AND S. PROKOFIEV’S SONATA, OP. 28: HISTORICAL, THEORETICAL, STYLISTIC AND PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATIONS by JANA KRAJČIOVÁ B.M., Northwestern State University of Louisiana, 2010 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2012 Approved by: Major Professor: Dr. Sławomir P. Dobrzański Abstract The following report analyzes compositions performed at the author’s Master’s Piano Recital on March 15, 2012. The discussed pieces are Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata in G major, BWV 916; Ludwig van Beethoven’s Sonata in E flat major, op. 31, No. 3; Frederic Chopin’s Ballade in F minor, op. 52; Leoš Janáček’s In The Mists: I. Andante, III. Andantino; and Sergei Prokofiev’s Sonata in A minor, op. 28. The author approaches the study from the historical, theoretical, stylistic and pedagogical perspectives. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... x Preface...........................................................................................................................................